The non-coagulate part of cheese, often referred to as whey, is a byproduct of the cheese-making process. When milk is curdled, it separates into solid curds (which become cheese) and liquid whey. Whey is primarily composed of water, lactose, proteins, vitamins, and minerals, and it plays a significant role in both the food industry and nutrition. While traditionally considered a waste product, whey is now valued for its high protein content and is commonly used in protein supplements, beverages, and other food products. Understanding whey’s composition and properties sheds light on its importance in cheese production and its broader applications in health and nutrition.

Explore related products

$36.52 $49.99

$69.99 $89.99

What You'll Learn

- Whey Composition: Contains water, lactose, proteins, vitamins, and minerals, separated during cheese making

- Whey Uses: Utilized in food, supplements, and animal feed for nutritional value

- Whey Proteins: Includes alpha-lactalbumin and beta-lactoglobulin, valuable for health benefits

- Whey Separation: Extracted through curdling milk, leaving solids as cheese curds

- Whey Benefits: Rich in amino acids, supports muscle growth and immune function

Whey Composition: Contains water, lactose, proteins, vitamins, and minerals, separated during cheese making

Whey, the liquid byproduct of cheese production, is often overlooked yet remarkably nutrient-dense. Its composition—primarily water, lactose, proteins, vitamins, and minerals—is a testament to its versatility and value. During cheesemaking, the curds (solid part) coagulate, leaving whey as the non-coagulated liquid. This separation process is not just a step in cheese production but a gateway to harnessing whey’s potential in food, health, and even animal feed industries.

Analyzing whey’s components reveals its functional and nutritional significance. Water constitutes about 93–94% of whey, making it a dilute yet rich solution. Lactose, the primary carbohydrate, accounts for 4–5% and is a natural sugar that can be further processed into lactose-free products or used as a sweetener. Proteins, comprising 0.8–1%, include high-quality whey proteins like beta-lactoglobulin and alpha-lactalbumin, which are prized for their bioavailability and muscle-building properties. Vitamins (e.g., B-complex) and minerals (e.g., calcium, potassium) round out its profile, making whey a holistic nutritional source.

For practical use, whey’s composition lends itself to various applications. In sports nutrition, 20–30 grams of whey protein isolate per day supports muscle recovery and growth, particularly in adults aged 18–50. Its lactose content can be a caution for those with intolerance, but hydrolyzed whey or lactose-free versions offer alternatives. In baking, whey’s proteins improve dough elasticity, while its lactose enhances browning and flavor. Even in agriculture, whey’s minerals and proteins enrich animal feed, reducing waste and promoting sustainability.

Comparatively, whey stands out against other dairy byproducts due to its low fat and high protein content. Unlike buttermilk or cream, whey is lean yet nutrient-rich, making it ideal for health-conscious consumers. Its separation during cheesemaking ensures purity, distinguishing it from raw milk. This unique composition positions whey as a cost-effective, eco-friendly resource, transforming what was once considered waste into a valuable commodity.

In conclusion, whey’s composition is a blend of simplicity and complexity, offering water, lactose, proteins, vitamins, and minerals in a single package. Its separation during cheesemaking is not just a technical step but a gateway to innovation. Whether in nutrition, food production, or sustainability, whey’s non-coagulated nature is its strength, proving that even the overlooked can be extraordinary.

The World's Largest Cheese: Unveiling the Colossal Dairy Marvel

You may want to see also

Whey Uses: Utilized in food, supplements, and animal feed for nutritional value

Whey, the liquid byproduct of cheese production, is often overlooked yet brimming with nutritional potential. Historically discarded as waste, it has emerged as a versatile ingredient across industries, valued for its protein content, vitamins, and minerals. This transformation from byproduct to resource highlights a shift towards sustainability and innovation in food utilization.

In the realm of food production, whey serves as a functional ingredient, enhancing texture, moisture, and nutritional profiles. It is commonly found in baked goods, where it improves dough elasticity and extends shelf life. For instance, adding 10-15% whey powder to bread recipes can increase protein content by up to 50%, making it a smart choice for health-conscious consumers. Whey’s natural sweetness also reduces the need for added sugars in products like granola bars and smoothies, aligning with dietary trends favoring low-sugar options.

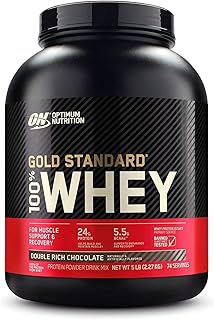

Supplements represent another significant application, leveraging whey’s high-quality protein for fitness and wellness. Whey protein isolate, containing over 90% protein, is a staple in post-workout recovery, with studies recommending 20-30 grams per serving for muscle repair and growth. Its rapid absorption rate makes it ideal for athletes and active individuals. Additionally, whey supplements often include branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), further supporting muscle endurance and recovery. For older adults, whey’s leucine content aids in combating age-related muscle loss, making it a valuable addition to diets for those over 65.

Beyond human consumption, whey plays a crucial role in animal feed, addressing nutritional needs in livestock and pets. Its cost-effectiveness and rich nutrient profile make it an excellent alternative to traditional feed components. In poultry farming, incorporating 5-10% whey into feed mixtures has been shown to improve egg production and shell quality. For dairy cows, whey supplementation supports lactation, enhancing milk yield. Pet food manufacturers also utilize whey for its palatability and nutritional benefits, particularly in high-protein dog and cat foods.

Practical implementation of whey in these areas requires consideration of its form—liquid, concentrate, or isolate—each suited to specific applications. For instance, liquid whey is ideal for animal feed due to its affordability, while whey isolate is preferred in supplements for its purity. Storage and processing methods are equally critical; whey must be pasteurized to prevent spoilage and ensure safety. For home use, whey powder can be incorporated into recipes by replacing 10% of flour with whey, balancing moisture and nutrition.

In conclusion, whey’s journey from cheese-making byproduct to a multifaceted resource underscores its untapped potential. Whether in food, supplements, or animal feed, its nutritional richness and versatility make it an invaluable asset in addressing modern dietary and sustainability challenges. By embracing whey, industries and individuals alike can maximize its benefits, turning what was once waste into a cornerstone of innovation.

Why Yellow and White American Cheese Taste Different: Unraveling the Mystery

You may want to see also

Whey Proteins: Includes alpha-lactalbumin and beta-lactoglobulin, valuable for health benefits

The non-coagulated part of cheese, known as whey, is a treasure trove of bioactive compounds, with whey proteins taking center stage. Among these, alpha-lactalbumin and beta-lactoglobulin are the most abundant, comprising approximately 20-25% and 50-60% of total whey protein, respectively. These proteins are not only essential for infant nutrition but also offer a plethora of health benefits for individuals of all ages.

From an analytical perspective, the unique amino acid composition of alpha-lactalbumin and beta-lactoglobulin contributes to their biological activity. Alpha-lactalbumin is rich in tryptophan, an essential amino acid that serves as a precursor for serotonin, a neurotransmitter involved in mood regulation. Beta-lactoglobulin, on the other hand, contains high levels of branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), which are crucial for muscle protein synthesis and recovery. Studies suggest that consuming 20-30 grams of whey protein, containing a balanced ratio of alpha-lactalbumin and beta-lactoglobulin, can promote muscle growth and repair, particularly in older adults and athletes.

In a comparative analysis, whey proteins have been shown to outperform other protein sources in terms of bioavailability and absorption. Unlike casein, the primary protein in cheese curds, whey proteins are rapidly digested and absorbed, making them an ideal choice for post-workout nutrition. Furthermore, whey proteins have a higher biological value (BV) than soy or pea protein, indicating their superior ability to support muscle growth and maintenance. For optimal results, individuals should aim to consume whey protein within 30 minutes of exercise, with a recommended dosage of 0.3-0.4 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight.

A persuasive argument for incorporating whey proteins into one's diet lies in their potential to support immune function and reduce inflammation. Beta-lactoglobulin, in particular, has been shown to possess immunomodulatory properties, helping to regulate the immune response and reduce oxidative stress. Alpha-lactalbumin, with its high cysteine content, serves as a precursor for glutathione, a powerful antioxidant that plays a critical role in cellular defense. To harness these benefits, consider adding a scoop of whey protein isolate (containing at least 90% protein) to your daily smoothie or oatmeal, ensuring a minimum intake of 10-15 grams of alpha-lactalbumin and beta-lactoglobulin.

For those seeking practical tips, it's essential to choose high-quality whey protein supplements that undergo minimal processing to preserve the integrity of alpha-lactalbumin and beta-lactoglobulin. Look for products that use cold-processing methods, such as microfiltration or ultrafiltration, to avoid denaturing the proteins. Additionally, individuals with lactose intolerance or dairy allergies should opt for whey protein isolates or hydrolysates, which contain minimal lactose and are less likely to trigger adverse reactions. When incorporating whey proteins into your diet, start with a low dosage (5-10 grams) and gradually increase to assess tolerance, particularly if you have a sensitive digestive system. By following these guidelines, you can unlock the full potential of whey proteins and experience their numerous health benefits.

Measuring Cheese: How Many Ounces in One Cube?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$19.97 $22.99

$25.16 $39.99

Whey Separation: Extracted through curdling milk, leaving solids as cheese curds

Whey separation is a fundamental process in cheese making, where the liquid component of milk is extracted, leaving behind the solid cheese curds. This transformation occurs through the curdling of milk, typically induced by adding rennet or acidic substances like lemon juice or vinegar. The curds, rich in casein proteins, solidify and separate from the whey, a nutrient-dense liquid containing lactose, vitamins, minerals, and proteins like whey protein. Understanding this process is crucial for both artisanal cheese makers and those seeking to utilize whey’s nutritional benefits.

From a practical standpoint, whey separation can be achieved at home with minimal equipment. Start by heating a gallon of milk to 55°C (130°F), then add 1-2 tablespoons of lemon juice or vinegar, stirring gently. Allow the mixture to rest for 10 minutes until curds form. Strain the mixture through a cheesecloth or fine-mesh strainer, collecting the whey in a bowl. The curds can be pressed into cheese, while the whey can be used in smoothies, baked goods, or as a protein supplement. Caution: Avoid overheating the milk, as it can affect the curdling process and the texture of the final product.

Analytically, whey’s composition makes it a valuable byproduct. It contains approximately 93% water and 7% solids, including lactose, whey protein, and minerals like calcium and potassium. Its low pH (around 4.6) and natural preservatives give it a longer shelf life compared to milk. For fitness enthusiasts, whey protein isolate—derived from further processing of whey—contains 90-95% protein, making it a popular supplement for muscle recovery. This highlights whey’s dual role as both a waste product in cheese making and a high-value nutritional resource.

Comparatively, whey separation differs from other milk-processing methods, such as yogurt making, where the goal is to retain the liquid portion. In cheese making, the focus is on isolating solids, while whey is often discarded or underutilized. However, its versatility rivals that of milk itself. For instance, whey can be fermented into beverages like kefir or used as a base for soups and sauces. This contrasts with the curds, which are primarily destined for cheese production, showcasing whey’s untapped potential in culinary and nutritional applications.

In conclusion, whey separation is more than a step in cheese making—it’s an opportunity to harness a nutrient-rich resource. By understanding the process and its outcomes, individuals can reduce food waste and incorporate whey into their diets creatively. Whether used as a protein boost or a cooking ingredient, whey exemplifies how every part of milk can serve a purpose, bridging tradition and innovation in food production.

Midnight Cheese Quest: My 3AM Hunt for Shredded Bliss

You may want to see also

Whey Benefits: Rich in amino acids, supports muscle growth and immune function

Whey, the liquid byproduct of cheese production, is often overlooked, yet it’s a nutritional powerhouse. Unlike the curds that form the solid part of cheese, whey is the non-coagulated portion, rich in proteins, vitamins, and minerals. Among its standout qualities is its high concentration of essential amino acids, particularly branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) like leucine, isoleucine, and valine. These compounds are the building blocks of muscle tissue, making whey a favorite among athletes and fitness enthusiasts. But its benefits extend beyond muscle growth; whey also bolsters immune function through its bioactive components, such as immunoglobulins and lactoferrin.

For those looking to harness whey’s muscle-building potential, timing and dosage matter. Research suggests consuming 20–30 grams of whey protein post-workout optimizes muscle protein synthesis, particularly in adults aged 18–50. This is because whey is rapidly absorbed, delivering amino acids to muscles when they need them most. For older adults, whey can counteract age-related muscle loss, known as sarcopenia. A daily intake of 25–30 grams, divided between meals, can support muscle maintenance and strength. Practical tip: blend whey protein into smoothies with fruits and vegetables for a nutrient-dense recovery drink.

Whey’s immune-supporting properties are equally compelling. Its immunoglobulins and lactoferrin act as natural defenders, enhancing the body’s ability to fight infections. Studies show that regular whey consumption can increase glutathione levels, a key antioxidant that strengthens immune cells. This is particularly beneficial for individuals with weakened immune systems or those under chronic stress. For immune support, aim for 10–20 grams of whey protein daily, either as a supplement or through whey-rich foods like ricotta cheese or whey-based beverages.

Comparing whey to other protein sources highlights its superiority in amino acid profile and bioavailability. Unlike plant-based proteins, which may lack certain essential amino acids, whey provides a complete protein source. It also outperforms casein, another milk protein, in terms of rapid absorption, making it ideal for post-exercise recovery. However, whey isn’t without limitations. Those with lactose intolerance or dairy allergies should opt for hydrolyzed or isolate forms, which contain minimal lactose. Always consult a healthcare provider before starting any new supplement regimen, especially if you have underlying health conditions.

Incorporating whey into your diet is simpler than you might think. Beyond protein powders, whey is found in products like Greek yogurt, cottage cheese, and even some baked goods. For a DIY approach, save the liquid from homemade ricotta cheese—it’s pure whey. Whether you’re an athlete aiming to build muscle or someone seeking to boost immunity, whey offers a versatile and effective solution. Its unique combination of amino acids and bioactive compounds makes it a standout in the world of nutrition, proving that the non-coagulated part of cheese is far from waste.

Finding Nacho Cheese at Target: A Quick Aisle-by-Aisle Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The non-coagulate part of cheese is the whey, which is the liquid that separates from the curds during the cheese-making process.

Whey does not coagulate because it primarily consists of water, lactose, proteins (such as whey proteins), and minerals, while the curds are formed by the coagulation of casein proteins through the action of rennet or acid.

Whey is not discarded; it is often used in various products, including protein supplements, animal feed, and even in making ricotta cheese.

Yes, whey can be consumed directly and is often used as a nutritional supplement due to its high protein content and health benefits.