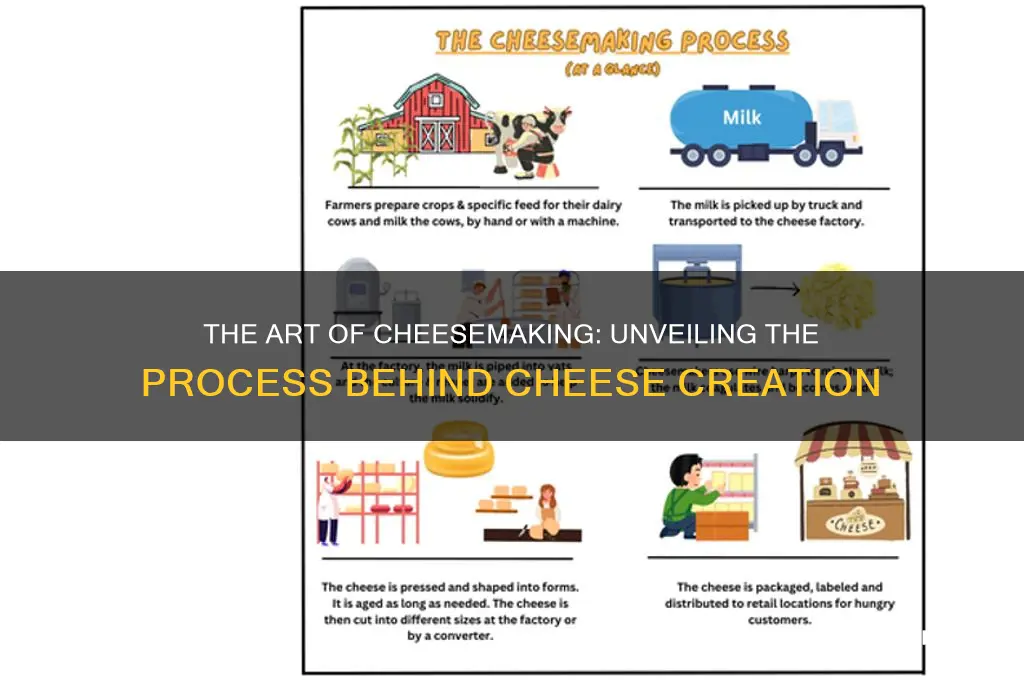

The process of making cheese, known as cheesemaking, is a fascinating blend of art and science that transforms milk into a diverse array of flavors, textures, and aromas. It begins with the selection of milk, typically from cows, goats, sheep, or buffalo, which is then pasteurized or used raw, depending on the desired outcome. The milk is coagulated using rennet or bacterial cultures, causing it to curdle into solid curds and liquid whey. The curds are then cut, stirred, and heated to release moisture and develop the desired texture. After draining the whey, the curds are pressed, salted, and often aged, during which bacteria and molds further transform the cheese, enhancing its flavor and character. This meticulous process, honed over centuries, results in the wide variety of cheeses enjoyed worldwide.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Process Name | Cheesemaking |

| Primary Steps | Curdling, Coagulation, Draining, Pressing, Aging |

| Key Ingredients | Milk (cow, goat, sheep, etc.), Coagulants (rennet, microbial enzymes), Starter Cultures (bacteria), Salt |

| Curdling Method | Acidification (by bacteria or acid addition) or Enzymatic (using rennet) |

| Coagulation | Formation of curds (solid milk proteins) and whey (liquid) |

| Draining | Separation of whey from curds to reduce moisture content |

| Pressing | Applying pressure to curds to form a cohesive mass |

| Aging (Ripening) | Controlled environment for bacterial and enzymatic activity to develop flavor and texture |

| Duration | Varies by cheese type (e.g., fresh cheeses: days; hard cheeses: months to years) |

| Temperature | Specific ranges for each step (e.g., curdling: 30°C; aging: 2-15°C) |

| pH Level | Adjusted during curdling (typically lowered to 4.6-6.0) |

| Outcome | Diverse cheese varieties (e.g., cheddar, mozzarella, brie) |

Explore related products

$8.8 $15.99

What You'll Learn

- Milk Selection: Choosing raw or pasteurized milk from cows, goats, or sheep as the base

- Coagulation: Adding rennet or acid to curdle milk, separating curds from whey

- Curd Cutting: Cutting curds into smaller pieces to release moisture and shape texture

- Draining & Pressing: Removing whey and pressing curds to form cheese blocks

- Aging & Ripening: Storing cheese to develop flavor, texture, and complexity over time

Milk Selection: Choosing raw or pasteurized milk from cows, goats, or sheep as the base

The foundation of any cheese lies in its milk, and the choice between raw and pasteurized, as well as the animal source—cow, goat, or sheep—sets the stage for flavor, texture, and complexity. Raw milk, unheated and untreated, retains its natural enzymes and bacteria, contributing to a richer, more nuanced flavor profile. However, it requires meticulous handling to avoid contamination. Pasteurized milk, heated to kill pathogens, offers consistency and safety but often lacks the depth of raw milk. This decision is not merely technical; it’s philosophical, balancing tradition with modernity.

Consider the animal source: cow’s milk, the most common, provides a mild, buttery base ideal for classics like cheddar or mozzarella. Goat’s milk, with its tangy, slightly sweet notes, shines in cheeses like chèvre or feta, while sheep’s milk, richer and creamier, is the backbone of indulgent varieties such as manchego or pecorino. Each milk type brings distinct characteristics, influenced by the animal’s diet, breed, and environment. For instance, grass-fed cows produce milk higher in conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), enhancing both nutritional value and flavor.

When selecting milk, factor in the desired cheese type and production scale. Raw milk is often preferred by artisanal cheesemakers for its complexity, but it demands strict hygiene protocols and shorter aging times to comply with regulations. Pasteurized milk, while more forgiving, may require the addition of starter cultures to replicate the microbial activity lost during heating. For home cheesemakers, pasteurized milk is a safer, more accessible option, though experimenting with raw milk (where legal) can yield extraordinary results.

Practical tips: If using raw milk, source it from a trusted, certified dairy to minimize risk. For pasteurized milk, avoid ultra-high temperature (UHT) treated varieties, as they lack the necessary proteins for proper curdling. When working with goat or sheep’s milk, adjust recipes to account for their higher fat and protein content, which can affect coagulation times. Always test milk quality before use—off flavors or odors will carry through to the final product.

Ultimately, milk selection is a pivotal decision in cheesemaking, shaping not only the end result but also the process itself. Whether prioritizing safety, flavor, or tradition, understanding the nuances of raw versus pasteurized and the unique qualities of each animal’s milk empowers cheesemakers to craft cheeses that are both intentional and exceptional.

Blood and Cheese's Brutal Killings: Unveiling the Victims in the Book

You may want to see also

Coagulation: Adding rennet or acid to curdle milk, separating curds from whey

Coagulation is the transformative step in cheesemaking where liquid milk transitions into a solid mass, setting the stage for all cheese varieties. This process hinges on the deliberate addition of coagulants—either rennet or acid—to disrupt milk’s natural stability, causing it to curdle. Rennet, derived from animal enzymes or microbial sources, is typically added at a precise dosage of 1/8 to 1/4 teaspoon per gallon of milk, depending on its strength and the desired cheese type. Acid coagulation, often achieved with vinegar, lemon juice, or citric acid, requires careful measurement: 1 tablespoon of vinegar or lemon juice per gallon of milk, or 1/4 teaspoon of citric acid dissolved in water, suffices for most recipes. The choice between rennet and acid influences not only the curd’s texture but also the flavor profile, with rennet yielding firmer, more complex curds and acid producing softer, fresher cheeses like ricotta or paneer.

The mechanics of coagulation are a delicate balance of chemistry and timing. When rennet is introduced, it activates chymosin, an enzyme that cleaves kappa-casein proteins, destabilizing the milk’s micelles and causing them to aggregate into curds. This process takes 30 to 60 minutes at an optimal temperature of 86–100°F (30–38°C), depending on the milk’s acidity and the rennet’s potency. Acid coagulation, in contrast, works by lowering the milk’s pH, forcing calcium ions to leave the micelles and causing them to collapse and bind together. This method is faster, often taking 5 to 15 minutes, but requires constant monitoring to avoid over-acidification, which can lead to a grainy texture. Both methods culminate in the same result: a clear separation of curds (milk solids) from whey (liquid), a visual and tactile milestone in cheesemaking.

Practical tips for mastering coagulation include ensuring milk is free of antibiotics, as they inhibit rennet’s enzymatic action, and pre-warming it to the target temperature for consistent results. For acid coagulation, always dilute acids in water before adding them to milk to prevent uneven curdling. Beginners should start with forgiving recipes like mozzarella (rennet-based) or queso blanco (acid-based) to build confidence. Advanced cheesemakers can experiment with double-coagulation techniques, combining rennet and acid to create layered textures, as seen in traditional cheeses like halloumi. Regardless of method, the key is patience: rushing coagulation risks weak curds, while over-waiting can lead to syneresis, where curds expel too much whey, compromising yield and texture.

Comparing rennet and acid coagulation reveals their distinct roles in shaping cheese diversity. Rennet-coagulated cheeses, such as cheddar or Parmesan, develop complex flavors and firm textures through prolonged aging, as the curds retain more moisture and fat. Acid-coagulated cheeses, like cottage cheese or chhena, are typically consumed fresh, emphasizing mild, milky flavors and crumbly or creamy textures. This contrast underscores why coagulation is not merely a functional step but a creative decision that defines a cheese’s identity. By understanding and controlling this process, cheesemakers can craft products that range from the simplest fresh cheeses to the most intricate aged varieties, each a testament to the art and science of coagulation.

Exploring Chinese Cuisine: Are Chilli Cheese Fries a Local Delight?

You may want to see also

Curd Cutting: Cutting curds into smaller pieces to release moisture and shape texture

Cheese making, known as cheesemaking, involves a series of precise steps, each influencing the final product’s flavor, texture, and appearance. Among these, curd cutting stands out as a pivotal moment where the cheese’s destiny is shaped—literally. This step involves slicing the coagulated milk (curd) into smaller pieces, a process that serves two critical purposes: releasing excess whey (moisture) and determining the cheese’s eventual texture. Without curd cutting, cheeses would lack the characteristic firmness, crumbly bite, or creamy mouthfeel that define varieties like cheddar, feta, or mozzarella.

Analytically, curd cutting is a delicate balance of science and art. The size of the curd pieces directly impacts moisture retention: smaller cuts expel more whey, resulting in harder, drier cheeses, while larger cuts retain moisture for softer textures. For example, cheddar curds are cut into pea-sized pieces to achieve a dense, crumbly structure, whereas mozzarella curds remain larger to preserve elasticity. Temperature and acidity during cutting further refine the outcome; a warmer curd releases whey faster, while higher acidity can tighten the curd’s structure. Mastering these variables allows cheesemakers to control the final product with precision.

Instructively, curd cutting requires careful timing and technique. Once the milk has coagulated into a solid mass, a long-bladed knife or curd cutter is used to slice through it methodically. For home cheesemakers, a clean, sterilized knife or even a spatula can suffice. The curd should be cut in a crisscross pattern, ensuring even-sized pieces. After cutting, the curds are gently stirred to encourage whey release. This step is repeated over several intervals, known as "healing," where the curds rest, firm up, and expel more moisture. Patience is key; rushing can damage the curds, while delaying can lead to over-softening.

Persuasively, curd cutting is where a cheesemaker’s skill truly shines. It’s the point of no return, where decisions made in seconds dictate the cheese’s future. A slight miscalculation in cut size or stirring force can alter the texture irreversibly. Yet, this step also offers creative freedom. By experimenting with cut sizes and techniques, cheesemakers can innovate, crafting unique textures that set their products apart. For instance, a slightly larger cut in a cheddar recipe might yield a creamier, more melt-in-your-mouth version, appealing to modern palates.

Descriptively, the act of curd cutting is a sensory experience. The curd, once a smooth, gelatinous mass, transforms under the knife’s edge into a mosaic of soft, wobbly pieces. The sound of the blade slicing through is subtle yet satisfying, a quiet testament to the cheese’s evolving nature. As the curds are stirred, whey pools around them, its milky opacity contrasting with the curd’s matte surface. The kitchen fills with the faint, tangy aroma of warming milk and lactic acid, a reminder of the microbial magic at play. This step is both methodical and meditative, a blend of craftsmanship and chemistry.

Comparatively, curd cutting in cheesemaking mirrors kneading in breadmaking—both are transformative steps that define the end product’s texture. Just as kneading develops gluten for a chewy loaf, curd cutting shapes the protein matrix for a firm or creamy cheese. However, while kneading is a hands-on, tactile process, curd cutting demands precision and restraint. Overworking bread dough can toughen it, but overcutting or stirring curds can expel too much whey, leaving the cheese dry and crumbly. Both processes highlight the importance of understanding the material’s behavior to achieve the desired result.

In conclusion, curd cutting is far more than a mere step in cheesemaking; it’s a defining moment that bridges science and artistry. Whether crafting a sharp cheddar or a delicate ricotta, this process demands attention to detail, creativity, and respect for the ingredients. By mastering curd cutting, cheesemakers unlock the potential to create cheeses that delight the senses and tell a story of craftsmanship. For anyone venturing into cheesemaking, this step is both a challenge and an opportunity—a chance to shape not just curds, but culinary experiences.

Mastering Last Stand in Left 4 Dead: Cheesy Strategies for Survival

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Draining & Pressing: Removing whey and pressing curds to form cheese blocks

The transformation of curds into cheese blocks is a delicate dance of moisture removal and consolidation, a process known as draining and pressing. This stage is crucial in determining the final texture and structure of the cheese, whether it’s the crumbly nature of feta or the dense firmness of cheddar. Whey, the liquid byproduct of curdling milk, must be expelled to concentrate the curds, and pressing ensures they bind into a cohesive mass. Without this step, cheese would remain a soft, shapeless mass, lacking the character and longevity we associate with aged varieties.

Draining begins immediately after the curds are cut and separated from the whey. For softer cheeses like ricotta, this might involve a simple straining through cheesecloth, allowing whey to drip away naturally. Harder cheeses, however, require more aggressive methods. The curds are often transferred to molds lined with cheesecloth or perforated containers that allow whey to escape. Time and temperature play critical roles here; warmer environments accelerate draining but risk overheating the curds, while cooler conditions slow the process but preserve their integrity. For example, cheddar curds are typically drained at around 90°F (32°C) for several hours to achieve the desired moisture level.

Pressing follows draining and is where the curds are transformed into a solid block. The pressure applied varies widely depending on the cheese type. Fresh cheeses like paneer may require minimal pressing, often just the weight of the whey above the curds in the mold. In contrast, semi-hard and hard cheeses like Gruyère or Parmesan demand significant force, sometimes up to 50 pounds per square inch, applied gradually over hours or even days. This step not only removes additional whey but also aligns the curd particles, creating a uniform texture. Pressing too quickly or with too much force can crush the curds, while too little pressure results in a crumbly, uneven block.

Practical tips for home cheesemakers include using weighted presses or even improvised setups, such as stacking heavy books on a wrapped mold. Monitoring the process is key; check the cheese periodically to ensure whey is being expelled without over-compressing the curds. For aged cheeses, flipping the block during pressing ensures even moisture distribution and prevents warping. Understanding the specific requirements of the cheese you’re making is essential, as each variety has its own draining and pressing profile.

In essence, draining and pressing are where the curds’ potential is realized, shaping the cheese’s final form and function. This phase bridges the gap between a liquid-like mass and a solid, sliceable product, showcasing the artistry and science of cheesemaking. Mastery of these steps allows for the creation of cheeses with diverse textures and flavors, from the creamy interior of Brie to the crystalline crunch of aged Gouda. It’s a testament to how precision in moisture control and pressure can elevate a simple ingredient into a culinary masterpiece.

Effective Rat Control: Big Cheese Bait Blocks Dosage Guide

You may want to see also

Aging & Ripening: Storing cheese to develop flavor, texture, and complexity over time

Cheese aging, or ripening, is a transformative process that elevates a simple curd into a complex, flavorful masterpiece. This stage is where the true artistry of cheesemaking unfolds, as time, temperature, and humidity work in harmony to develop the cheese's unique character. Imagine a young, mild cheese evolving into a robust, crumbly vintage cheddar or a creamy Camembert with its signature gooey center – all achieved through the magic of aging.

The Science Behind Ripening:

Aging cheese is a delicate dance of microbiology. After the initial cheesemaking process, which involves curdling milk, draining whey, and pressing curds, the cheese is ready for its transformation. During aging, bacteria and molds, either naturally present or added, break down the cheese's proteins and fats. This enzymatic activity releases amino acids and fatty acids, contributing to the cheese's flavor and aroma. For instance, the bacteria *Brevibacterium linens* is responsible for the distinctive orange rind and pungent smell of Limburger cheese.

Aging Environments:

The environment in which cheese is aged is critical. Traditional cheese caves provide the ideal conditions, offering consistent cool temperatures (around 50–55°F) and high humidity (85-95%). These caves often have natural mold and bacteria cultures that contribute to the cheese's flavor. Modern cheesemakers use climate-controlled rooms, carefully monitoring temperature and humidity to replicate these conditions. For home aging, a wine refrigerator set to the desired temperature and humidity level can be a suitable alternative.

Time, the Master Craftsman:

Aging duration varies widely, from a few weeks to several years, depending on the desired outcome. Fresh cheeses like mozzarella or chèvre are typically ready in days, while hard cheeses such as Parmesan or Gouda require months or even years. For example, a young cheddar aged for 3-6 months will have a mild, sharp flavor, whereas an extra-sharp cheddar aged for 1-2 years develops a deeper, more complex taste with a crumbly texture. This extended aging process allows for the gradual breakdown of proteins, resulting in a more intense flavor profile.

Caring for Aging Cheese:

Proper care is essential during the ripening process. Regularly turning and flipping the cheese ensures even moisture distribution and prevents mold from settling in one spot. Brining or washing the cheese with solutions like saltwater or beer encourages the growth of specific bacteria or molds, adding unique flavors. For instance, washing cheese with brine promotes the growth of *Geotrichum candidum*, a mold that creates a bloomy, edible rind on cheeses like Brie. Additionally, maintaining cleanliness in the aging environment is crucial to prevent unwanted bacterial growth.

In the world of cheesemaking, aging is where science meets art. It's a patient process that rewards those who understand the intricacies of time, temperature, and microbiology. Whether you're a cheesemaker or an enthusiast, appreciating the aging process adds a new dimension to the enjoyment of this ancient craft. With the right conditions and care, a simple block of curd can become a culinary masterpiece, offering a sensory experience like no other.

House of the Dragon: Cheese's Fate Explained and Debated

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The process of making cheese is called cheesemaking.

The main steps include milk preparation, coagulation (curdling the milk), cutting the curd, cooking and stirring, draining, salting, molding, pressing, and aging.

Bacteria play a crucial role in fermentation, converting lactose (milk sugar) into lactic acid, which helps in curdling the milk and developing flavor and texture in the cheese.

Yes, cheesemaking can be done at home with basic tools like a thermometer, stainless steel pot, cheesecloth, cheese press, and starter cultures. Simple cheeses like mozzarella or ricotta are great for beginners.