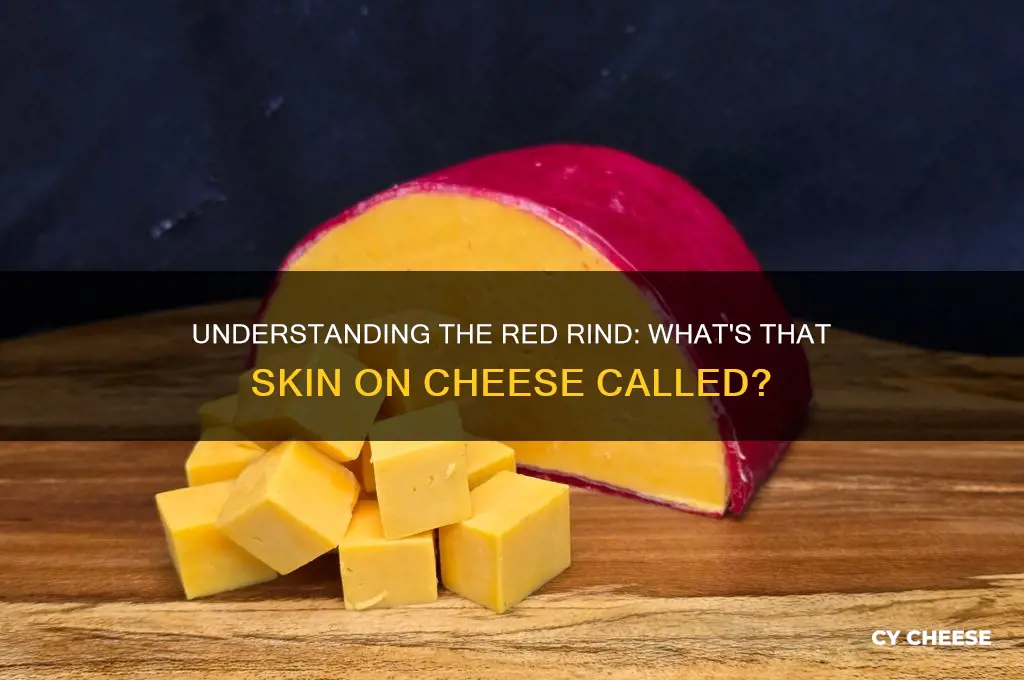

The red skin on certain cheeses, often seen on varieties like Brie or Camembert, is known as a rind or crust. This rind is typically the result of a specific type of mold, such as *Penicillium camemberti*, which is intentionally introduced during the cheese-making process. The mold grows on the surface, creating a protective layer that helps preserve the cheese while contributing to its distinctive flavor and texture. Depending on the cheese, the rind can range from soft and bloomy to hard and wax-like, and it often plays a crucial role in the cheese's overall development and character. While some rinds are edible and add to the sensory experience, others are meant to be removed before consumption.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name | Rind or Wax Coating (specifically red wax for cheeses like Gouda or Edam) |

| Purpose | Protects the cheese from mold, retains moisture, and enhances flavor |

| Composition | Typically made of paraffin wax, sometimes mixed with colorants (e.g., annatto for red color) |

| Texture | Smooth, waxy, and non-edible |

| Appearance | Bright red, though colors can vary (e.g., yellow, black) |

| Common Cheeses | Gouda, Edam, Cheddar (when coated in red wax) |

| Edibility | Not edible; should be removed before consuming |

| Functionality | Acts as a barrier against air and contaminants, slows down aging |

| Removal | Easily peeled off before slicing or serving |

| Historical Use | Traditionally used for preservation and transportation |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Natural Rind Formation: Bacteria and mold growth during aging creates the red skin on certain cheeses

- Washed-Rind Cheeses: Red skin often results from brine washing during the cheese-making process

- Bacterial Cultures: Specific bacteria like *Brevibacterium linens* produce the red or orange hue

- Aging Process: Extended aging allows bacteria to develop the characteristic red rind

- Edibility of Rind: Most red rinds are safe to eat, adding flavor and texture to the cheese

Natural Rind Formation: Bacteria and mold growth during aging creates the red skin on certain cheeses

The red skin on certain cheeses, often referred to as a natural rind, is a fascinating byproduct of the aging process. This vibrant hue isn’t artificially added but emerges organically through the interplay of bacteria and mold. During aging, microorganisms like *Brevibacterium linens* (responsible for the red-orange color) and various molds colonize the cheese surface, creating a protective barrier that influences flavor, texture, and appearance. This natural rind is a hallmark of cheeses such as Époisses, Limburger, and Brick, where the red pigmentation is both a visual signature and a testament to traditional cheesemaking techniques.

To understand how this rind forms, consider the aging environment. Cheeses with red rinds are typically aged in humid, temperature-controlled spaces that encourage microbial growth. The bacteria and molds consume lactose and proteins on the cheese surface, producing pigments like carotenoids and other metabolites that contribute to the red color. For example, *Brevibacterium linens* metabolizes amino acids into compounds that give the rind its distinctive orange-red shade. This process isn’t random; cheesemakers carefully control factors like humidity (around 90%) and temperature (12–15°C) to foster the desired microbial activity without spoilage.

Practical tips for appreciating or working with these cheeses include storing them in breathable containers to maintain rind integrity and avoiding plastic wrap, which can trap moisture and cause spoilage. When serving, the rind is often edible and adds complexity to the flavor profile, though some prefer to remove it due to its strong aroma. For home cheesemakers, replicating this process requires inoculating the cheese with *Brevibacterium linens* cultures and monitoring aging conditions meticulously. Commercially, these cheeses are often washed with brine or alcohol during aging to encourage specific microbial growth and enhance color development.

Comparatively, the red rind stands apart from waxed or cloth-bound rinds, which are externally applied to protect the cheese. Natural rinds, in contrast, are living ecosystems that evolve with the cheese, contributing to its character. This distinction highlights the artistry of traditional cheesemaking, where time, microbes, and environment converge to create something unique. For enthusiasts, understanding this process deepens appreciation for the craft and the science behind these cheeses, making each bite a connection to centuries-old traditions.

Easy Bacon, Egg, and Cheese Croissants with Great Value Ingredients

You may want to see also

Washed-Rind Cheeses: Red skin often results from brine washing during the cheese-making process

The red skin on certain cheeses is a distinctive feature that often sparks curiosity. This characteristic hue is not a cause for concern but rather a sign of a specific cheese-making technique. In the world of washed-rind cheeses, this red exterior is a result of a deliberate and carefully controlled process.

The Brine Washing Technique:

Imagine a cheese aging room where artisans carefully tend to their creations. During the cheese-making journey, some varieties undergo a unique transformation. The red skin, a signature of washed-rind cheeses, is achieved through a process called brine washing. This involves regularly rubbing the cheese's surface with a brine solution, often containing salt and bacteria cultures. The brine encourages the growth of specific bacteria, such as *Brevibacterium linens*, which is responsible for the distinctive red or orange color. This bacteria is naturally present in the environment and on the skin, and it thrives in the moist conditions created by the brine.

Aging and Flavor Development:

As the cheese ages, the brine washing continues, and the red skin becomes more pronounced. This process is not merely aesthetic; it significantly influences the cheese's flavor and texture. The bacteria break down proteins and fats, creating a complex array of flavors, from nutty and earthy to pungent and savory. The longer the aging process, the more intense the flavors become. For instance, a young washed-rind cheese might have a mild, creamy taste, while an aged one could offer a robust, spicy experience.

Varieties and Pairings:

Washed-rind cheeses come in various forms, each with its own unique character. From the French Époisses with its soft, creamy interior and potent aroma to the Italian Taleggio, known for its fruity notes, these cheeses offer a diverse sensory experience. When serving, consider pairing them with beverages that complement their bold flavors. A full-bodied red wine or a strong ale can stand up to the intensity of these cheeses. For a non-alcoholic option, try a crisp apple cider or a rich, dark chocolate to balance the cheese's pungency.

A Sensory Adventure:

Exploring washed-rind cheeses is an adventure for the senses. The red skin is not just a visual marker but a promise of a unique taste experience. As you cut through the exterior, the aroma escapes, hinting at the flavors within. Each bite reveals a complex interplay of textures and tastes, from the initial tang to the lingering richness. This category of cheese is a testament to the art of cheese-making, where a simple brine wash transforms a humble curd into a culinary masterpiece. So, the next time you encounter a cheese with a red skin, embrace the opportunity to indulge in a truly distinctive gourmet delight.

Mastering Arc Weapons: Cheesy Tactics to Defeat Guardians Easily

You may want to see also

Bacterial Cultures: Specific bacteria like *Brevibacterium linens* produce the red or orange hue

The vibrant red or orange rind on certain cheeses isn't just a decorative touch—it's a signature of specific bacterial cultures at work. Among these, *Brevibacterium linens* stands out as the primary artist behind this colorful transformation. This bacterium, commonly found on human skin and contributing to foot odor, thrives in the humid, salty environment of aging cheese. Its metabolic processes produce pigments that lend the cheese its distinctive hue, a process both fascinating and functional.

To cultivate this effect, cheesemakers carefully introduce *Brevibacterium linens* to the cheese surface during aging. The bacteria require a specific environment: high humidity, moderate temperatures (around 12–18°C), and a pH level between 5.0 and 6.5. Over weeks or months, the bacteria multiply, breaking down proteins and fats on the rind. This activity releases pigments like carotenoids, which manifest as the red or orange color. For optimal results, maintain a consistent environment and monitor the cheese regularly to ensure even coloration.

While *Brevibacterium linens* is the star, other bacteria and yeasts often play supporting roles. For instance, *Debaryomyces hansenii*, a yeast, can coexist with *B. linens*, enhancing the rind's texture and flavor. However, balance is key. Overgrowth of *B. linens* can lead to an overpowering ammonia smell, detracting from the cheese's appeal. To prevent this, control the salt concentration (typically 2–3% in the brine) and adjust ventilation to limit excessive bacterial activity.

Practical tips for home cheesemakers: Start with a washed-rind cheese like Munster or Limburger, which naturally support *B. linens*. Inoculate the cheese surface with a commercial *B. linens* culture or a piece of rind from a mature cheese. Age the cheese in a humid environment, misting the rind occasionally to keep it moist. Patience is crucial—the coloration process can take 4–8 weeks. For a deeper red, extend the aging period and ensure the bacteria have ample nutrients by using a richer milk base.

In summary, the red skin on cheese is a testament to the interplay between *Brevibacterium linens* and its environment. By understanding and controlling factors like humidity, temperature, and pH, cheesemakers can harness this bacterial culture to create visually striking and flavorful cheeses. Whether you're a professional or a hobbyist, mastering this process adds a unique dimension to your craft.

Master Iron Banner: Cheese Strategies for Unstoppable Win Streaks

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Aging Process: Extended aging allows bacteria to develop the characteristic red rind

The red skin on certain cheeses, often referred to as a "washed rind" or "smear-ripened," is a result of a meticulous aging process that fosters the growth of specific bacteria. This distinctive rind is not merely a byproduct of time but a deliberate outcome of extended aging, during which bacteria like *Brevibacterium linens* flourish. These microorganisms are responsible for the cheese's signature red or orange hue, as well as its robust, earthy flavor profile. Understanding this process reveals the artistry behind cheeses like Époisses, Munster, and Limburger, where the rind is as crucial to the cheese's identity as its interior.

To achieve this characteristic red rind, cheesemakers employ a technique known as "washing" or "smearing," where the cheese's surface is repeatedly brushed or rubbed with a brine solution, often containing salt, water, and sometimes alcohol. This practice creates a humid environment conducive to bacterial growth. Over weeks or even months, *Brevibacterium linens* and other microbes metabolize the proteins and fats on the cheese's surface, producing the red pigments and complex flavors. The longer the aging process, the more pronounced the rind's color and aroma become, transforming the cheese into a bold, sensory experience.

For home cheesemakers or enthusiasts, replicating this process requires patience and precision. Start by ensuring the cheese is stored in a cool, humid environment, ideally at 50–55°F (10–13°C) with 85–90% humidity. Apply the brine solution every few days, using a ratio of 20 grams of salt per liter of water, and optionally add a small amount of wine or beer to encourage bacterial activity. Monitor the cheese closely, as extended aging can lead to over-ripening if not managed carefully. The goal is to strike a balance where the rind develops its signature red color without overwhelming the cheese's interior texture and taste.

Comparatively, the aging process for red-rinded cheeses differs significantly from that of harder cheeses like Cheddar or Parmesan, which rely on mold or natural drying. Washed-rind cheeses thrive on bacterial activity, while others focus on enzymatic breakdown or moisture loss. This distinction highlights the diversity of cheese aging techniques and the unique role bacteria play in creating specific characteristics. By embracing extended aging and bacterial cultivation, cheesemakers craft products that are not just food but expressions of science and tradition.

In conclusion, the red skin on cheese is no accident but a testament to the interplay of time, bacteria, and craftsmanship. Extended aging, coupled with careful washing techniques, allows *Brevibacterium linens* to develop the rind's iconic color and flavor. Whether you're a cheesemaker or a connoisseur, appreciating this process deepens your understanding of the art behind these bold, complex cheeses. Next time you encounter a washed-rind cheese, remember: its red rind is a story of patience, precision, and microbial magic.

Mastering the Deep Roads: Cheesing the Lyrium Demon in Dragon Age

You may want to see also

Edibility of Rind: Most red rinds are safe to eat, adding flavor and texture to the cheese

The red skin on certain cheeses, often referred to as the rind, is typically a result of bacterial or mold cultures applied during the aging process. This rind serves both functional and aesthetic purposes, protecting the cheese while developing its unique flavor profile. When encountering a red rind, the first question that arises is whether it’s safe to eat. The answer is reassuring: most red rinds are not only edible but also contribute significantly to the cheese’s overall experience. Unlike wax coatings, which are meant to be removed, red rinds are designed to be consumed, adding complexity through their earthy, nutty, or slightly tangy notes.

From a practical standpoint, eating the rind enhances the sensory journey of the cheese. For instance, the red rind on cheeses like Mimolette or Tomme de Savoie provides a satisfying contrast in texture—firm and slightly chewy against the softer interior. To fully appreciate this, pair rind-included bites with complementary flavors such as crusty bread, crisp apples, or a robust red wine. However, it’s essential to consider the cheese’s age and storage conditions. Younger cheeses with red rinds may have milder flavors, while older varieties can develop stronger, more pungent profiles. If the rind appears overly dry, cracked, or discolored, it’s best to trim it before consumption.

For those hesitant to eat the rind, start with milder varieties like Red Leicester, where the rind’s flavor is subtle and approachable. Gradually explore bolder options like Brick cheese, whose rind contributes a distinct, buttery richness. Children and individuals with sensitive palates may prefer the rind removed, but for adults, embracing the rind unlocks the cheese’s full character. Always store red-rind cheeses properly—wrapped in wax or parchment paper, not plastic, to maintain humidity without promoting excess moisture, which can lead to spoilage.

Incorporating red-rind cheeses into your diet is not just about taste but also about tradition. Many European cheesemakers have perfected the art of red rind cultivation over centuries, using natural annatto for coloring and specific bacterial cultures for flavor. By eating the rind, you’re honoring this craftsmanship while maximizing the nutritional benefits, as rinds often contain higher concentrations of probiotics and vitamins. So, the next time you slice into a red-rind cheese, don’t shy away—embrace the rind as an integral part of the cheese’s story and your culinary adventure.

Perfect Cheese Portions: How Much Sliced Cheese for 100 Sandwiches?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The red skin on cheese is typically called a rind or a coating, often dyed with annatto, a natural food coloring derived from the achiote tree.

Yes, the red skin on cheese is generally edible, though some prefer to remove it due to its texture or flavor.

The red color is often added using annatto to enhance appearance, differentiate cheese types, or mimic traditional aging processes.

The red skin itself usually has a mild or neutral flavor, but it can contribute to the overall texture and appearance of the cheese.

Yes, you can remove the red skin if desired, though it is safe to eat and often adds to the cheese's character.