The white exterior of Brie cheese, known as the rind, is a defining characteristic of this beloved French cheese. Composed primarily of Penicillium camemberti, a type of mold, the rind plays a crucial role in the cheese's development, contributing to its distinctive flavor, texture, and appearance. As the cheese ages, the mold breaks down the curd, creating a creamy interior while the rind itself remains edible, offering a slightly earthy and mushroom-like taste that complements the rich, buttery center. This unique combination of rind and interior is what makes Brie a standout in the world of soft cheeses.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name | Bloom (or rind) |

| Composition | Primarily Penicillium camemberti mold |

| Appearance | White, fuzzy, velvety texture |

| Purpose | Protects the cheese during aging, contributes to flavor and texture development |

| Edibility | Generally considered safe to eat, though some prefer to remove it |

| Flavor | Mildly earthy, mushroom-like, enhances the overall taste of the cheese |

| Texture | Soft, slightly tacky, contrasts with the creamy interior |

| Formation | Develops naturally during the aging process due to mold growth |

| Maintenance | Requires proper humidity and temperature control during aging |

| Health Impact | Contains beneficial bacteria and enzymes, but may cause allergic reactions in some individuals |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Mold Type: White exterior is Penicillium camemberti, a safe, edible mold used in Brie production

- Purpose of Mold: Protects cheese, aids ripening, and develops Brie's signature flavor and texture

- Edibility: The rind is safe to eat, adding earthy, nutty, and mushroom-like flavors

- Texture Difference: Rind is firmer and smoother compared to the creamy, soft interior

- Aging Effect: As Brie ages, the rind becomes thinner and more integrated with the cheese

Mold Type: White exterior is Penicillium camemberti, a safe, edible mold used in Brie production

The white exterior of Brie cheese is not just a decorative feature but a crucial component of its flavor, texture, and safety. This distinctive layer is composed of *Penicillium camemberti*, a specific type of mold intentionally introduced during the cheese-making process. Unlike harmful molds that can spoil food, *P. camemberti* is safe and edible, playing a vital role in transforming fresh milk into the creamy, complex Brie we know and love. Its presence is a hallmark of authenticity, distinguishing Brie from other cheeses and contributing to its unique sensory experience.

From a practical standpoint, understanding *Penicillium camemberti* is essential for both cheese makers and consumers. For producers, the mold is carefully cultured and sprayed onto the cheese’s surface, where it thrives in the cool, humid environment of aging rooms. Over 4–6 weeks, it breaks down the cheese’s exterior, softening the interior and creating the characteristic bloomy rind. For consumers, recognizing this mold as intentional and safe eliminates unnecessary concerns about spoilage. In fact, removing the rind not only alters the flavor profile but also removes a key source of umami and earthy notes that define Brie.

Comparatively, *Penicillium camemberti* sets Brie apart from cheeses like Cheddar or Gouda, which rely on bacterial cultures rather than surface molds. Its role is akin to that of *Penicillium roqueforti* in blue cheese, though the latter grows internally and produces a sharper flavor. The subtlety of *P. camemberti* lies in its ability to enhance rather than overpower, creating a delicate balance between the rich, buttery interior and the slightly tangy, velvety rind. This distinction makes Brie a versatile cheese, ideal for pairing with fruits, nuts, or crusty bread.

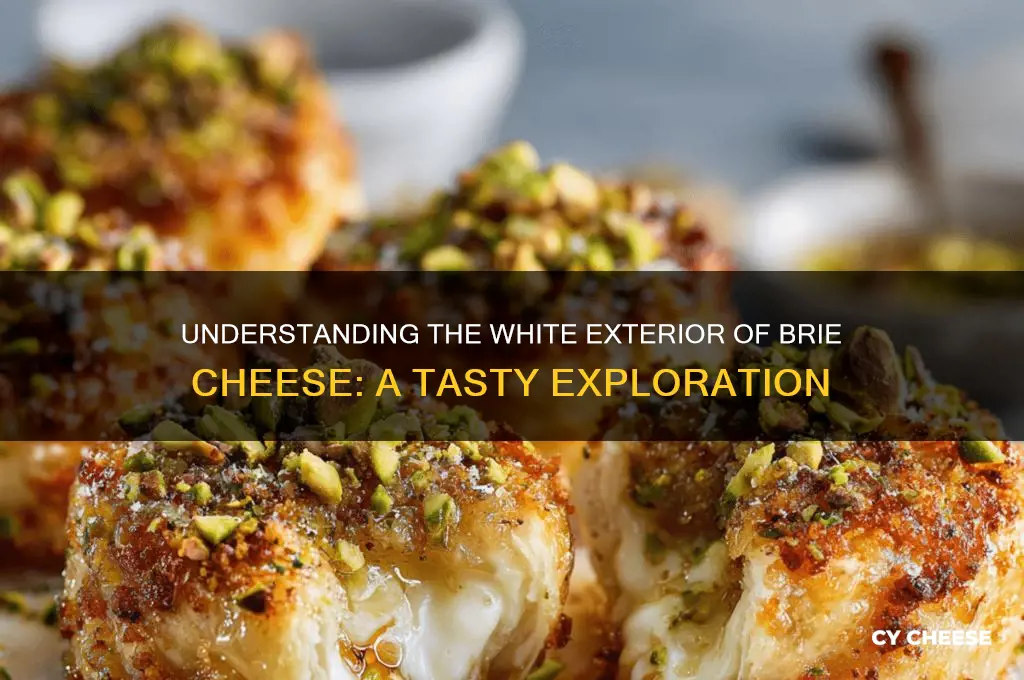

For those hesitant to consume the rind, consider this: *Penicillium camemberti* is not only safe but also contributes to the cheese’s nutritional profile. It contains enzymes that aid in digestion and may offer probiotic benefits, though in smaller quantities compared to fermented foods like yogurt. To fully appreciate Brie, serve it at room temperature, allowing the rind to soften and meld with the interior. Avoid heating it excessively, as this can cause the mold to become rubbery. Instead, bake it briefly in a small ovenproof dish, letting the heat gently liquefy the center for a decadent, spoonable treat.

In conclusion, the white exterior of Brie is far more than a superficial layer—it’s the result of a meticulously controlled process involving *Penicillium camemberti*. This mold is not just safe to eat but integral to the cheese’s identity, offering a sensory experience that engages both palate and intellect. By embracing the rind, you’re not just savoring Brie; you’re honoring the craftsmanship and science behind one of the world’s most beloved cheeses.

Exploring the Versatile Sides of a Cheese Grater: A Complete Guide

You may want to see also

Purpose of Mold: Protects cheese, aids ripening, and develops Brie's signature flavor and texture

The white exterior of Brie cheese, known as the rind, is a living layer of mold, primarily Penicillium camemberti. This mold is not merely a byproduct of the cheese-making process but a deliberate addition with a specific purpose. It serves as a protective barrier, a catalyst for ripening, and a developer of the cheese’s signature flavor and texture. Without this mold, Brie would lack its characteristic creamy interior and earthy, nutty notes.

Consider the protective role of the mold first. The rind acts as a shield, preventing harmful bacteria from penetrating the cheese while allowing the interior to mature in a controlled environment. This is particularly crucial during the aging process, which typically lasts 4 to 6 weeks. During this time, the mold competes with unwanted microorganisms, ensuring the cheese remains safe for consumption. For home cheesemakers, maintaining a consistent temperature of 50–55°F (10–13°C) and humidity of 90–95% is essential to support this protective function without encouraging spoilage.

Next, the mold actively aids in ripening by breaking down the cheese’s proteins and fats. Enzymes produced by Penicillium camemberti soften the interior, transforming it from firm to velvety. This enzymatic activity is temperature-sensitive; too warm, and the cheese may over-ripen or develop ammonia flavors; too cold, and ripening stalls. Commercial producers often use pre-measured mold cultures to ensure consistency, but artisanal cheesemakers rely on natural inoculation, monitoring the cheese closely to achieve the desired texture.

Finally, the mold is responsible for Brie’s complex flavor profile. As it grows, it produces compounds that contribute earthy, mushroom-like, and slightly grassy notes. These flavors develop gradually, with the intensity peaking around 6–8 weeks of aging. Tasting Brie at different stages reveals how the mold’s influence evolves: younger cheeses are milder, while older ones exhibit deeper, more pronounced flavors. Pairing Brie with acidic accompaniments like fruit or wine can balance its richness, enhancing the mold’s contribution to the overall sensory experience.

In summary, the white mold on Brie is not just a surface feature but a functional component that protects, ripens, and flavors the cheese. Understanding its role allows both makers and enthusiasts to appreciate Brie’s craftsmanship and tailor its aging and consumption for optimal enjoyment. Whether crafting Brie at home or selecting the perfect wheel at a market, recognizing the mold’s purpose elevates the experience of this iconic cheese.

Can Cheese Sticks Keep You in Ketosis? The Snack Dilemma

You may want to see also

Edibility: The rind is safe to eat, adding earthy, nutty, and mushroom-like flavors

The white exterior of Brie cheese, known as the rind, is not merely a protective layer but a culinary asset. Composed primarily of Penicillium camemberti, a mold that thrives in the aging process, this rind is entirely safe to consume. Its edibility is a testament to the craftsmanship behind Brie, where the mold’s growth is carefully controlled to enhance both texture and flavor. Unlike some cheese rinds that are waxed or too tough to eat, Brie’s rind is soft and integrates seamlessly with the interior, offering a complete sensory experience.

Eating the rind introduces a spectrum of flavors that elevate Brie from a simple cheese to a complex delicacy. Notes of earthiness, nuttiness, and a subtle mushroom-like undertone emerge from the rind, contrasting the creamy, mild interior. These flavors are a result of the mold’s enzymatic activity, which breaks down proteins and fats during aging. For optimal enjoyment, pair rind-on Brie with foods that complement its umami profile, such as crusty bread, honey, or fresh fruit. Avoid overpowering it with strong spices or acidic ingredients that may clash with its delicate balance.

Incorporating the rind into your Brie experience requires no special preparation—simply slice and serve. However, for those new to rind consumption, start with a small portion to acclimate your palate. Children and adults alike can safely enjoy it, though individual preferences may vary. If serving to guests, inform them of the rind’s edibility and its flavor contribution, as some may be hesitant due to unfamiliarity. For a more pronounced flavor, opt for aged Brie, where the rind’s complexity deepens over time.

While the rind is safe, quality matters. Ensure the Brie is stored properly—refrigerated and wrapped in wax or parchment paper to maintain humidity without suffocating the mold. Avoid plastic wrap, which can cause the rind to sweat and spoil. If the rind appears overly dry, cracked, or discolored (beyond the typical white mold), it may indicate poor handling or age, and the cheese should be discarded. By respecting the rind’s role and treating it with care, you unlock the full potential of Brie’s flavor profile.

Ultimately, the rind of Brie is not just edible but essential to the cheese’s character. Its earthy, nutty, and mushroom-like flavors provide a depth that the interior alone cannot achieve. Embracing the rind transforms Brie from a mere ingredient into a centerpiece, worthy of savoring in its entirety. Whether enjoyed on a cheese board or melted into a dish, the rind ensures every bite is a celebration of artisanal craftsmanship and culinary tradition.

Revamp Your Four Cheese Gnocchi: Creative Twists for a Delicious Makeover

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Texture Difference: Rind is firmer and smoother compared to the creamy, soft interior

The white exterior of Brie cheese, known as the rind, is a defining feature that contrasts sharply with its interior. This texture difference is not merely a coincidence but a result of the cheese-making process. The rind forms as the cheese ages, developing a firmer, smoother consistency that acts as a protective barrier. In contrast, the interior remains creamy and soft, creating a sensory experience that evolves from the moment the cheese is cut. Understanding this duality is key to appreciating Brie’s unique character.

From a practical standpoint, the rind’s texture serves a functional purpose. Its firmness prevents the soft interior from oozing out, making Brie easier to handle and transport. For those new to Brie, slicing through the rind reveals the dramatic contrast in textures, a moment that highlights the craftsmanship behind this cheese. To fully enjoy Brie, consider serving it at room temperature, allowing the rind to soften slightly while the interior becomes even creamier. This enhances the textural interplay, making each bite a balance of smooth exterior and luscious center.

A comparative analysis reveals why the rind’s texture is essential to Brie’s identity. Unlike cheeses with crumbly or wax-coated exteriors, Brie’s rind is edible and integral to its flavor profile. The firmness of the rind complements the softness inside, creating a harmonious contrast that elevates the eating experience. For instance, pairing Brie with crackers or bread allows the rind’s smoothness to counterbalance the crunch, while the creamy interior spreads effortlessly. This textural duality is a testament to the precision of traditional cheese-making techniques.

For those looking to experiment, the rind’s texture can be a creative canvas. Try incorporating Brie into recipes where its contrasting textures shine, such as baked Brie with honey and nuts, where the rind holds its shape while the interior melts. Alternatively, use the rind as a natural mold for cheese fondue, adding depth to the dish. However, caution should be exercised when heating Brie, as excessive heat can cause the rind to become rubbery. Aim for a gentle bake at 350°F (175°C) for 10–15 minutes to preserve its ideal texture.

In conclusion, the texture difference between Brie’s rind and its interior is a deliberate feature that enhances both its functionality and sensory appeal. By understanding and appreciating this contrast, cheese enthusiasts can elevate their enjoyment of Brie, whether savoring it on its own or incorporating it into culinary creations. The rind’s firmness and smoothness, paired with the interior’s creaminess, make Brie a masterpiece of texture and taste.

String Cheese Incident’s Eclipse Festival Performance Dates Revealed

You may want to see also

Aging Effect: As Brie ages, the rind becomes thinner and more integrated with the cheese

The white exterior of Brie cheese, known as the rind, is a living, breathing ecosystem of mold cultures, primarily *Penicillium camemberti*. This rind is not just a protective layer but a dynamic component that evolves as the cheese ages. Over time, the rind undergoes a transformation that affects both its texture and its relationship with the interior paste. As Brie matures, the rind becomes thinner and more integrated with the cheese, a process that significantly influences the flavor, aroma, and overall eating experience.

From an analytical perspective, this aging effect is a result of enzymatic activity and moisture migration. As the cheese ages, the mold continues to break down the curd, releasing enzymes that soften the interior. Simultaneously, moisture moves outward, causing the rind to become more pliable and less distinct from the paste. This integration is not merely a physical change but a chemical one, as the mold’s metabolites permeate the cheese, deepening its earthy, nutty, and slightly mushroomy flavors. For optimal results, store Brie at 50–55°F (10–13°C) and 85% humidity, allowing it to age for 4–6 weeks to observe this effect fully.

Instructively, understanding this aging process can guide how you handle and consume Brie. Younger Brie, aged 2–3 weeks, will have a firmer, more pronounced rind that contrasts with the softer interior. As it ages further, the rind becomes almost imperceptible, making it safe and desirable to eat. To maximize flavor, let aged Brie sit at room temperature for 30–60 minutes before serving. This allows the integrated rind and paste to soften evenly, creating a creamy, cohesive texture. Pair it with crusty bread, fresh fruit, or a glass of sparkling wine to complement its complex profile.

Comparatively, the aging effect in Brie contrasts with cheeses like Camembert, which has a similar rind but ages more rapidly due to its smaller size. Brie’s larger diameter slows the aging process, allowing for a gradual integration of the rind. This slower transformation is why Brie can develop a more nuanced flavor profile over time, whereas Camembert may become overly runny if aged too long. For those experimenting with aging, monitor Brie weekly after the 4-week mark, noting changes in rind thickness and flavor intensity to determine your preferred stage of maturity.

Descriptively, the aged Brie rind is a testament to the artistry of cheesemaking. Its once chalky, matte surface evolves into a velvety, ivory-hued exterior that melds seamlessly with the interior. The rind’s thinning is not a sign of deterioration but a mark of refinement, as the cheese becomes more harmonious in texture and taste. When sliced, the rind’s integration is evident in the way it clings to the paste, creating a unified bite that balances richness with a subtle tang. This transformation is a reminder that patience in aging yields a cheese that is greater than the sum of its parts.

Why Milk Fails Keto While Cheese Succeeds: Unraveling the Dairy Dilemma

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The white on the outside of Brie cheese is a layer of edible mold, specifically *Penicillium camemberti*, which is intentionally cultivated during the aging process.

Yes, the white mold on Brie cheese is safe to eat. It is a natural part of the cheese-making process and contributes to the cheese's flavor and texture.

The white mold, *Penicillium camemberti*, is added to Brie cheese to create its characteristic bloomy rind, enhance its creamy texture, and develop its rich, nutty flavor during aging.

While you can remove the white mold if you prefer, it is entirely edible and safe. Leaving it on enhances the overall flavor and experience of the cheese.