The white stuff often found on cheese can be a cause for curiosity or concern, but it’s typically harmless and even a sign of quality. This white substance is usually one of two things: mold or tyrosine crystals. Mold, especially on aged or blue cheeses, is intentional and part of the cheese-making process, adding flavor and texture. On the other hand, tyrosine crystals, which appear as small, crunchy white specks, are naturally occurring amino acids that form as cheese ages, particularly in harder varieties like Parmesan or aged Gouda. While neither is harmful, understanding the difference ensures you can confidently enjoy your cheese.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name | Lactose crystals, tyrosine crystals, mold, or salt crystals |

| Appearance | White, powdery, or crystalline |

| Texture | Dry, gritty, or flaky |

| Cause | Natural aging process, high moisture content, or surface mold growth |

| Common Cheeses | Aged cheeses (e.g., Parmesan, Cheddar), blue cheeses, or moist cheeses (e.g., Mozzarella, Brie) |

| Edibility | Generally safe to eat; mold should be avoided if not intentional (e.g., in blue cheese) |

| Prevention | Proper storage (refrigeration, airtight containers), controlling humidity |

| Health Impact | Harmless unless mold is unintended or causes allergies |

| Taste Impact | May add a slightly crunchy texture or nutty flavor (tyrosine crystals) |

| Misconception | Often mistaken for mold, but lactose/tyrosine crystals are natural and safe |

Explore related products

$13.48 $14.13

What You'll Learn

- Mold Growth: White mold on cheese can be safe or harmful, depending on the type

- Crystallization: White crystals form due to amino acid buildup, common in aged cheeses

- Surface Mold: Added intentionally in some cheeses for flavor, like Brie or Camembert

- Yeast Colonies: White spots caused by yeast, often harmless but affect texture and taste

- Salt or Calcium: White powder from excess salt or calcium lactate crystals, safe to eat

Mold Growth: White mold on cheese can be safe or harmful, depending on the type

Discovering white mold on cheese often sparks concern, but not all mold is created equal. Some cheeses, like Brie or Camembert, boast a velvety white rind that’s not only intentional but also integral to their flavor profile. This mold, typically *Penicillium camemberti*, is safe and desirable, contributing to the cheese’s creamy texture and earthy notes. However, if your cheese wasn’t meant to have mold—say, a block of cheddar or mozzarella—that white fuzz could signal spoilage. The key lies in identifying the type of mold and the cheese variety, as this determines whether it’s a culinary feature or a health risk.

To assess white mold on cheese, start by examining its appearance and location. Safe molds on specialty cheeses like Gorgonzola or Stilton appear as uniform, powdery coatings or veining, often blue-green but sometimes white. Harmful molds, on the other hand, tend to be irregular, discolored, or slimy, and they may spread beyond the surface. If the cheese smells ammonia-like or off-putting, discard it immediately. For hard cheeses like Parmesan, you can often cut away the moldy part (plus an extra inch) and consume the rest, but soft cheeses with mold should be thrown out entirely due to their higher moisture content, which allows mold to penetrate deeply.

Understanding the science behind mold growth helps demystify its presence. Mold thrives in damp, cool environments, making cheese an ideal host. While some molds are benign or even beneficial, others produce mycotoxins that can cause illness. For instance, *Aspergillus* molds can produce aflatoxins, which are harmful even in small amounts. To minimize risk, store cheese properly—wrap it in wax or parchment paper, not plastic, which traps moisture, and keep it in the coldest part of your refrigerator. Regularly inspect cheese, especially if it’s past its prime, and trust your instincts: when in doubt, throw it out.

For those who enjoy mold-ripened cheeses, knowing how to handle them safely is essential. Always purchase these cheeses from reputable sources, as improper production can introduce harmful molds. Pregnant individuals, the elderly, and those with weakened immune systems should avoid mold-ripened cheeses altogether, as they may pose a higher risk of infection. When serving, use clean utensils to prevent cross-contamination, and consume the cheese promptly after opening. By respecting the nuances of mold growth, you can savor the delights of artisanal cheeses while safeguarding your health.

Cheese and Bacon Balls: Real Bacon or Just Flavorful Illusion?

You may want to see also

Crystallization: White crystals form due to amino acid buildup, common in aged cheeses

Ever noticed tiny white specks on your aged cheddar or Parmesan? Those aren’t mold or salt—they’re amino acid crystals, a natural byproduct of the aging process. As cheese matures, moisture evaporates, concentrating proteins like tyrosine and calcium lactate. Over time, these proteins bind and crystallize, forming the crunchy, slightly salty bits that cheese enthusiasts often prize. Think of them as the cheese equivalent of a wine’s legs—a sign of complexity and depth.

To understand why this happens, consider the chemistry. During aging, enzymes break down milk proteins into amino acids, which then migrate through the cheese matrix. As moisture levels drop, these amino acids become saturated and precipitate out, forming crystals. This process is more common in hard, aged cheeses like Parmigiano-Reggiano or aged Gouda, where low moisture content accelerates crystallization. Soft cheeses, with higher water activity, rarely develop these crystals.

If you’re unsure whether the crystals are safe, rest assured: they’re not only harmless but also a mark of quality. However, texture preferences vary. Some enjoy the added crunch and umami boost, while others find it off-putting. To minimize crystallization, store cheese in a humid environment (around 50-60% humidity) and wrap it in wax or parchment paper, not plastic, which traps moisture and accelerates protein breakdown.

For those who embrace the crystals, seek out cheeses aged 12 months or longer. Parmesan, aged cheddar, and Grana Padano are excellent choices. Pair them with a full-bodied red wine or a crisp apple to complement the savory, nutty flavor the crystals enhance. And remember: these white specks aren’t a flaw—they’re a testament to time, craftsmanship, and the transformative power of aging.

Colby vs. Colby Jack: Unraveling the Cheese Confusion

You may want to see also

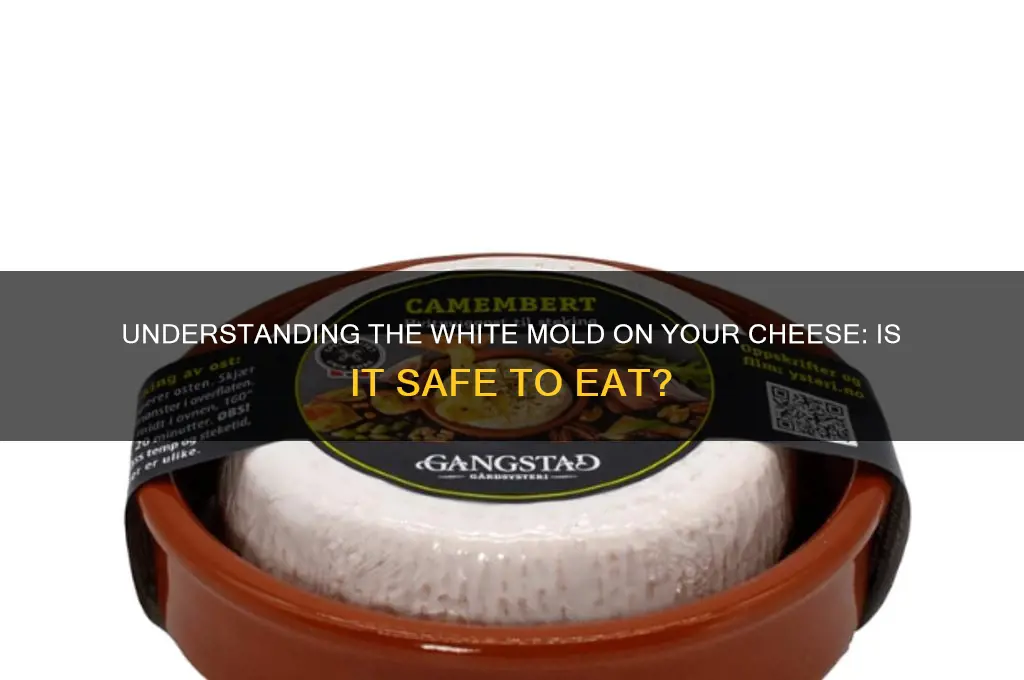

Surface Mold: Added intentionally in some cheeses for flavor, like Brie or Camembert

The white stuff on your cheese might not be a cause for alarm—it could be surface mold, a deliberate addition in certain cheeses to enhance flavor and texture. Unlike the mold that grows on forgotten leftovers, this type is carefully cultivated and essential to the cheese’s character. Take Brie and Camembert, for instance: their iconic bloomy rinds are the result of *Penicillium camemberti*, a mold introduced during production. This mold forms a velvety white exterior as the cheese ages, breaking down proteins and fats to create a creamy interior and complex, earthy notes.

To understand its role, consider the process. After curds are formed and shaped, the cheese is inoculated with *Penicillium camemberti* spores, either by spraying or dipping. Over 3–4 weeks, the mold grows, enveloping the cheese in a thin, edible rind. This isn’t just aesthetic—the enzymes produced by the mold tenderize the cheese, transforming it from firm to oozy. For optimal flavor, serve Brie or Camembert at room temperature; chilling dulls the mold’s contributions.

While surface mold is safe and desirable in these cheeses, it’s not interchangeable with other molds. For example, blue cheese uses *Penicillium roqueforti*, which penetrates the interior, creating veins. In contrast, bloomy rind molds stay on the surface, fostering a distinct, milder profile. If you spot white mold on a hard cheese like cheddar, however, that’s a sign of spoilage—a key distinction to remember.

Practical tip: if your Brie or Camembert develops ammonia-like aromas or a slimy texture, it’s overripe. To extend its life, wrap it in wax or parchment paper, not plastic, which traps moisture and accelerates decay. For those wary of mold, start with younger versions of these cheeses; they’ll have a firmer texture and milder flavor, easing you into the experience.

In short, the white stuff on Brie or Camembert isn’t a flaw—it’s a feature. Embrace it as part of the cheese’s artistry, a testament to the interplay of microbiology and craftsmanship. Next time you slice into one, savor the rind; it’s where the magic happens.

Cacique Cheese Restock Update: When Will It Be Available Again?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Yeast Colonies: White spots caused by yeast, often harmless but affect texture and taste

Ever noticed small, white spots dotting the surface of your cheese? These are often yeast colonies, a natural occurrence in aged cheeses like cheddar, Gouda, or Parmesan. Unlike mold, which can be fuzzy or discolored, yeast colonies appear as pinpoint dots or slightly raised patches. While they’re generally harmless, their presence can subtly alter the cheese’s texture and flavor profile, introducing a tangy or earthy note that some enthusiasts appreciate.

To identify yeast colonies, examine the cheese under good lighting. Unlike mold, which spreads in threads or patches, yeast colonies are discrete and uniform in size. If you’re unsure, smell the cheese—yeast colonies typically don’t produce the sharp, musty odor associated with spoilage. However, if the spots are accompanied by off-putting smells or sliminess, discard the cheese, as this could indicate bacterial contamination.

For those who prefer their cheese without yeast colonies, proper storage is key. Keep cheese in the refrigerator at 35–40°F (2–4°C) and wrap it in wax or parchment paper, which allows it to breathe while minimizing moisture buildup. Avoid plastic wrap, as it traps humidity and encourages yeast growth. If yeast colonies appear, gently scrape them off with a clean knife, ensuring you remove only the affected area.

While yeast colonies are safe to consume, their impact on texture and taste can be polarizing. Some cheeses, like aged cheddars, may develop a drier, crumbly texture due to yeast activity, while others might gain a complexity that enhances their flavor. If you’re crafting cheese at home, monitor humidity levels during aging—ideally between 80–85%—to control yeast growth. For commercial cheeses, trust the manufacturer’s handling guidelines, as they’re designed to balance safety and quality.

Ultimately, yeast colonies are a testament to cheese’s living, breathing nature. Embrace them as part of the artisanal experience, or take steps to minimize their presence—either way, understanding their role empowers you to enjoy cheese on your terms. Whether you’re a casual consumer or a connoisseur, knowing what those white spots signify ensures every bite is informed and intentional.

Wider Than Tall: The Ultimate Nacho Cheese Experience Explained

You may want to see also

Salt or Calcium: White powder from excess salt or calcium lactate crystals, safe to eat

Ever noticed a fine white powder on the surface of your aged cheeses, like Parmesan or cheddar? That's often salt or calcium lactate crystals, a natural and safe part of the aging process. These crystals form as moisture evaporates, leaving behind concentrated minerals. Think of them as the cheese equivalent of fleur de sel—a sign of quality and flavor intensity. Unlike mold or spoilage, these crystals are not only harmless but also a culinary bonus, adding a delightful crunch and umami punch to your cheese board.

From a compositional standpoint, calcium lactate crystals are a byproduct of the breakdown of lactose during aging. As bacteria metabolize lactose, lactic acid is produced, which can combine with calcium to form these microscopic crystals. Salt crystals, on the other hand, are simply excess salt that has migrated to the surface. Both types of crystals are more common in harder, longer-aged cheeses, where moisture loss is greater. For example, a 24-month aged Parmigiano-Reggiano is more likely to develop these crystals than a young, moist mozzarella. Understanding this process not only reassures you about safety but also deepens your appreciation for the cheese’s craftsmanship.

If you’re concerned about the appearance of these crystals, rest assured: they’re entirely safe to eat and can even enhance your experience. However, if you prefer a smoother texture, gently brush them off with a clean cloth or parchment paper before serving. For cooking, these crystals can be a secret weapon—grind them into a powder and sprinkle over pasta or popcorn for a savory boost. Keep in mind that while they’re safe, excessive salt intake is still a consideration, especially for those monitoring sodium levels. A typical 1-ounce serving of crystal-laden cheese might contain 150–200 mg of sodium from these crystals alone, so portion awareness is key.

Comparing these crystals to other white substances on cheese, like mold, highlights their benign nature. Mold, often blue or green, indicates a different type of cheese (like Roquefort) or potential spoilage in others. The white crystals, however, are a textural and flavor feature, not a defect. While moldy cheese (outside of varieties meant to have it) should be discarded, crystallized cheese is a treasure. This distinction is crucial for both safety and enjoyment, ensuring you don’t waste perfectly good cheese or accidentally consume something harmful.

Incorporating crystallized cheese into your diet is simple. Pair a chunk of crystal-rich cheddar with a crisp apple for a textural contrast, or shave Parmesan with crystals over a salad for added depth. For a more adventurous approach, melt crystallized cheese into a fondue—the crystals will dissolve, enriching the flavor. Remember, these crystals are a mark of time and tradition, not a flaw. Embrace them as part of the cheese’s story, and you’ll elevate both your palate and your culinary confidence.

Maggot-Infested Delicacy: Exploring Casu Marzu, the Controversial Cheese

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The white stuff on your cheese is typically mold or crystallized lactose, depending on the type of cheese. Hard cheeses like Parmesan may develop harmless lactose crystals, while softer cheeses might grow mold if not stored properly.

If the white stuff is lactose crystals, it’s safe and can add a pleasant crunch. However, if it’s mold on soft or semi-soft cheese, it’s best to discard the cheese, as mold can indicate spoilage. Hard cheeses with surface mold can often be salvaged by cutting off the moldy part.

Store cheese properly in the refrigerator, wrapped in wax or parchment paper, and avoid plastic wrap, which can trap moisture. For longer storage, use airtight containers or cheese paper. Regularly inspect cheese and consume it before it spoils.