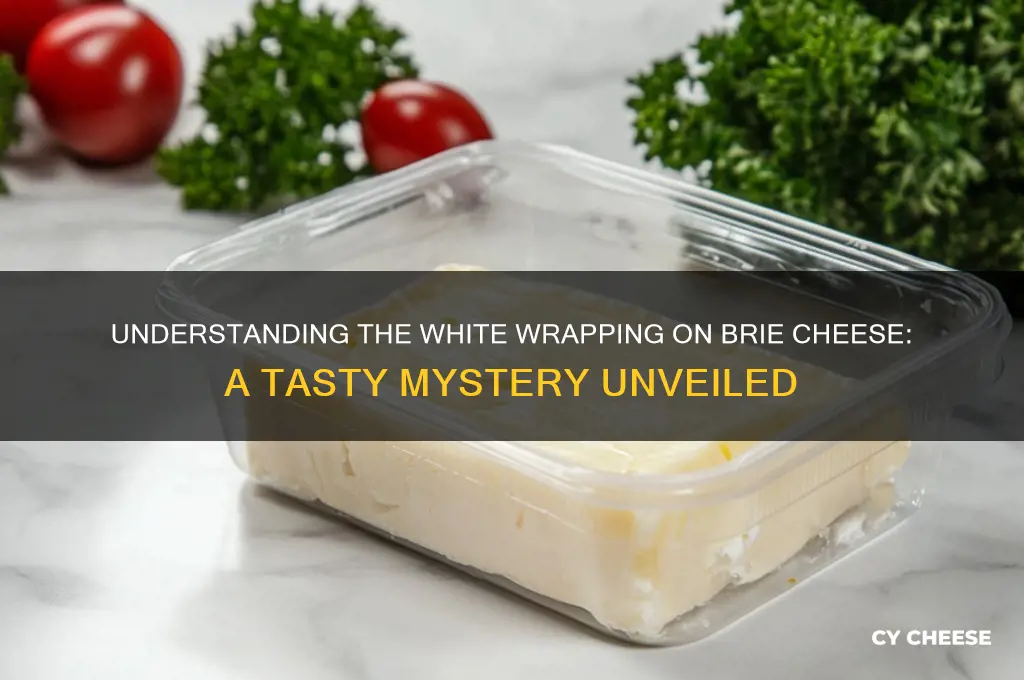

The white wrapping on Brie cheese, known as the rind, is a distinctive and essential component of this beloved French cheese. Composed primarily of mold, specifically Penicillium camemberti, the rind forms during the aging process, creating a protective barrier that helps the cheese ripen evenly. Its velvety texture and slightly earthy flavor contrast beautifully with the creamy interior, making it a topic of both culinary interest and curiosity. While some enjoy eating the rind for its added complexity, others prefer to remove it, sparking debates about the best way to savor this classic cheese. Understanding the role and composition of the rind enhances appreciation for Brie’s unique characteristics and its place in the world of artisanal cheeses.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name | Bloom (or Rind) |

| Color | White |

| Texture | Soft, velvety, and slightly fuzzy |

| Composition | Primarily Penicillium camemberti mold |

| Function | Protects the cheese during aging, contributes to flavor and texture development |

| Edibility | Generally considered edible, though some prefer to remove it |

| Flavor | Mild, earthy, and slightly mushroomy |

| Appearance | Uniform white coating with a matte finish |

| Formation | Develops naturally during the aging process |

| Maintenance | Requires proper humidity and temperature control during aging |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Origin of the Wrapping: Traditional method using mold-resistant, edible white penicillium candidum rind

- Purpose of the Rind: Protects cheese, aids aging, and adds flavor during maturation

- Edibility of the Wrapping: The white rind is safe and edible, enhancing texture and taste

- Types of Brie Rinds: Variations include bloomy, washed, or mixed rinds based on production

- How the Rind Forms: Natural mold growth during aging creates the characteristic white exterior?

Origin of the Wrapping: Traditional method using mold-resistant, edible white penicillium candidum rind

The white wrapping on Brie cheese isn’t a wrapping at all—it’s a living, edible rind formed by *Penicillium candidum*, a mold deliberately introduced during production. This rind is the cornerstone of Brie’s identity, a product of centuries-old tradition rather than modern packaging. Unlike external wrappings, this natural coating serves multiple purposes: protecting the cheese, fostering flavor development, and contributing to its signature texture. Understanding its origin reveals a masterful interplay of microbiology and craftsmanship.

To create this rind, cheesemakers follow a precise process. After curdling milk and shaping the cheese, the surface is inoculated with *Penicillium candidum* spores, often through a spray or bath. The mold thrives in the cool, humid aging environment, gradually forming a velvety white layer. This isn’t accidental growth—it’s a controlled fermentation, where the mold’s enzymes break down fats and proteins, creating Brie’s creamy interior and nutty aroma. The rind’s thickness and texture can vary based on aging time, typically 4–6 weeks, with longer aging yielding a more pronounced flavor.

What makes *Penicillium candidum* ideal for Brie? Its mold-resistant properties prevent unwanted bacteria from spoiling the cheese, while its edible nature ensures the rind is safe to consume. Unlike synthetic wrappings, this natural rind is part of the cheese itself, blending seamlessly into the eating experience. For home cheesemakers, replicating this method requires maintaining a temperature of 50–55°F (10–13°C) and 90% humidity during aging. Commercial producers often use pre-measured spore cultures to ensure consistency, but the principle remains rooted in tradition.

Comparing this to modern cheese production highlights its uniqueness. While many cheeses today use wax or plastic coatings, Brie’s rind is a testament to the art of letting nature do the work. It’s a reminder that sometimes the oldest methods are the most effective—and delicious. For those hesitant to eat the rind, consider this: it’s not just safe, but it encapsulates the full flavor profile of the cheese. Cutting it off is like skipping the crust of a perfectly baked loaf.

In practice, appreciating Brie’s rind means serving it thoughtfully. Let the cheese come to room temperature to soften both the interior and the rind, enhancing their melded textures. Pair it with crusty bread, fresh fruit, or a glass of Champagne to complement its earthy, buttery notes. For storage, wrap the cheese in wax paper or breathable cheese paper to maintain humidity without suffocating the rind. By honoring this traditional method, you’re not just eating cheese—you’re savoring history.

4C Graded Cheese Recall Alert: What You Need to Know

You may want to see also

Purpose of the Rind: Protects cheese, aids aging, and adds flavor during maturation

The white wrapping on Brie cheese, known as the rind, is far more than a mere outer layer. It is a living, breathing component that plays a critical role in the cheese's development. Composed primarily of Penicillium camemberti, a white mold, the rind forms a protective barrier that shields the delicate interior from spoilage and contamination. This natural defense mechanism allows the cheese to age gracefully, preventing unwanted bacteria from infiltrating while maintaining the ideal environment for controlled fermentation. Without this rind, Brie would be susceptible to rapid decay, losing its signature texture and flavor profile.

Beyond protection, the rind actively participates in the aging process, acting as a catalyst for enzymatic reactions that transform the cheese's interior. As the mold grows, it breaks down proteins and fats, softening the paste and creating the creamy, spreadable consistency Brie is celebrated for. This process is not merely passive; the rind's microbial activity introduces subtle earthy and nutty flavors, enriching the cheese's sensory experience. For optimal results, artisanal cheesemakers often regulate temperature and humidity during aging, ensuring the rind develops evenly and contributes harmoniously to the cheese's maturation.

Flavor development is another key function of the rind, as it serves as a conduit for complex taste profiles. During aging, the mold interacts with the cheese's surface, producing compounds that add depth and character. These flavors range from mild mushroom notes in younger Brie to more pronounced, tangy undertones in aged varieties. To enhance this process, some producers introduce specific strains of mold or adjust aging conditions to tailor the rind's impact. For instance, a cooler aging environment can slow mold growth, resulting in a milder rind flavor, while warmer conditions accelerate it, intensifying the taste.

Practical considerations for enjoying Brie highlight the rind's role. While the rind is edible and safe to consume, its texture and flavor may not appeal to all palates. Those seeking a smoother, more uniform experience can remove the rind before serving, though this comes at the cost of losing some of the cheese's complexity. For maximum flavor, pairing Brie with complementary foods—such as crusty bread, fresh fruit, or honey—can balance the rind's earthy notes. When storing Brie, wrap it in wax or parchment paper to allow the rind to breathe, preserving its integrity and preventing moisture buildup that could lead to spoilage. Understanding the rind's purpose not only deepens appreciation for Brie but also guides its proper handling and enjoyment.

Paneer vs. Cheese: Unraveling the Distinct Differences and Uses

You may want to see also

Edibility of the Wrapping: The white rind is safe and edible, enhancing texture and taste

The white wrapping on Brie cheese, often referred to as the rind, is not merely a protective layer but an integral part of the cheese itself. Contrary to common misconceptions, this rind is entirely safe to eat and, in fact, plays a crucial role in enhancing both the texture and flavor of the cheese. Composed primarily of Penicillium camemberti, a type of mold intentionally introduced during the cheesemaking process, the rind develops a soft, bloomy exterior that contrasts beautifully with the creamy interior. For those hesitant to consume it, consider this: the rind is where much of the cheese’s complexity originates, offering earthy, nutty, and slightly mushroomy notes that elevate the overall experience.

From a culinary perspective, eating the rind is not just acceptable but encouraged. Professional chefs and cheese aficionados alike emphasize that removing the rind deprives the cheese of its full potential. When serving Brie, allow it to come to room temperature to ensure the rind softens and melds seamlessly with the interior. Pairing the cheese with crusty bread, fresh fruit, or a drizzle of honey highlights the rind’s subtle flavors. For those new to Brie, start by taking small bites that include both the rind and the interior to appreciate how the two components work in harmony.

Nutritionally, the rind is harmless for most individuals, though those with mold allergies or compromised immune systems should exercise caution. For everyone else, the rind adds a negligible amount of calories while contributing significantly to the sensory experience. Interestingly, the mold on the rind is the same type used in other soft cheeses like Camembert, further underscoring its safety and culinary value. If you’re still unsure, begin by tasting a small portion of the rind on its own to familiarize yourself with its texture and flavor before enjoying it as part of the whole cheese.

Comparatively, the rind of Brie stands apart from the hard, wax-like rinds of cheeses like Gouda or Cheddar, which are typically inedible. The soft, velvety texture of Brie’s rind makes it indistinguishable from the cheese itself when consumed properly. This distinction is essential for understanding why the rind should never be discarded. By embracing the rind, you’re not only respecting the craftsmanship of the cheesemaker but also unlocking the full spectrum of flavors and textures that make Brie a beloved staple in cheese boards and recipes alike.

In practical terms, storing Brie correctly ensures the rind remains intact and flavorful. Keep the cheese in its original wrapping and refrigerate it, but remove it from the fridge at least an hour before serving to allow it to soften. If the rind appears overly dry or cracked, it may indicate improper storage, but it’s still safe to eat. For optimal enjoyment, pair Brie with beverages like sparkling wine or light-bodied reds, which complement the rind’s earthy undertones. By treating the rind as an essential component rather than an afterthought, you’ll discover why Brie is celebrated as a masterpiece of cheesemaking.

Cheese Bridge Area Secret Exit: Unveiling the Hidden Path

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Types of Brie Rinds: Variations include bloomy, washed, or mixed rinds based on production

The white wrapping on Brie cheese, often referred to as its rind, is far more than a protective layer—it’s a living, breathing component that defines the cheese’s flavor, texture, and character. Brie rinds fall into three primary categories: bloomy, washed, and mixed, each shaped by distinct production methods. Understanding these variations not only enhances appreciation but also guides pairing and serving choices.

Bloomy rinds, the most common type, are achieved through the introduction of *Penicillium camemberti* during production. This mold forms a velvety, edible white exterior that encases the cheese. As the cheese ages, typically 4–6 weeks, the rind softens the interior, creating a creamy texture. Bloomy rinds are mild and slightly nutty, making them ideal for beginners or those pairing with delicate flavors like honey or fresh fruit. To maximize enjoyment, serve bloomy-rind Brie at room temperature, allowing the rind to meld seamlessly with the paste.

In contrast, washed rinds undergo a different transformation. These cheeses are periodically brushed with brine, wine, or beer during aging, fostering the growth of *Brevibacterium linens*. This process results in a sticky, orange-hued rind with a robust, earthy aroma. Washed-rind Brie, often aged 6–8 weeks, offers a bolder flavor profile, balancing funkiness with richness. Pair it with hearty accompaniments like crusty bread or dark beer to complement its intensity. Caution: the rind’s pungency can overpower subtle flavors, so consider removing it if serving to sensitive palates.

Mixed rinds represent a fusion of techniques, blending the best of both worlds. Producers might start with a bloomy rind and later wash the cheese to introduce complexity. These hybrids often age for 8–10 weeks, developing layered flavors—creamy at the center, with hints of tanginess from the washed exterior. Mixed-rind Brie is versatile, suitable for both casual and sophisticated settings. Experiment with pairings like spiced nuts or aged balsamic to highlight its nuanced character.

Choosing the right Brie depends on personal preference and occasion. For a crowd-pleasing option, opt for bloomy rind; for adventurous palates, washed or mixed rinds deliver depth. Always store Brie in the refrigerator, wrapped in wax paper to maintain humidity, and bring to room temperature before serving. By understanding these rind variations, you’ll elevate your cheese experience, turning a simple snack into a sensory journey.

Uncovering the Slice Count: Kraft Singles Cheese Mystery Explained

You may want to see also

How the Rind Forms: Natural mold growth during aging creates the characteristic white exterior

The white exterior of Brie cheese, often mistaken for a wrapping, is actually a natural rind formed through a meticulous aging process. This transformation begins with the introduction of Penicillium camemberti, a specific mold culture, to the cheese’s surface. Unlike artificial coatings, this mold grows organically, creating a protective layer that defines Brie’s signature appearance and texture. The process is both scientific and artisanal, blending microbiology with traditional cheesemaking techniques.

To understand rind formation, consider the aging environment. Brie is typically aged in cool, humid conditions for 4–6 weeks. During this time, the mold spores bloom, consuming lactose and proteins on the cheese’s surface. This metabolic activity produces a white, velvety rind that is edible and integral to the cheese’s flavor profile. The mold’s growth is carefully monitored; too much humidity can lead to excessive fuzziness, while too little can halt development. Cheesemakers often adjust temperature (around 12°C or 54°F) and airflow to ensure optimal conditions.

Comparatively, the rind of Brie differs from those of harder cheeses like Cheddar or Gruyère, which form through bacterial activity rather than mold. Brie’s rind is softer, more delicate, and contributes a mild, earthy flavor that contrasts with the creamy interior. This duality is a hallmark of soft-ripened cheeses, where the rind and paste (interior) develop in tandem. For home enthusiasts, replicating this process requires precision: using unpasteurized milk (to allow natural microbial activity), applying mold cultures evenly, and maintaining consistent aging conditions.

A practical tip for appreciating Brie’s rind is to let the cheese warm to room temperature before serving. This softens the rind, integrating it seamlessly with the interior for a balanced bite. While some prefer to avoid the rind due to its stronger flavor or texture, it is entirely safe to eat and enhances the overall experience. For those aging Brie at home, monitor the rind’s appearance weekly; a healthy rind should remain white and free of discoloration or excessive moisture. If mold appears blue or green, it indicates contamination, and the cheese should be discarded.

In conclusion, the white rind on Brie is not a wrapping but a living testament to the cheese’s aging journey. Its formation is a delicate interplay of mold, time, and environment, resulting in a product that is as scientifically fascinating as it is culinarily delightful. Understanding this process not only deepens appreciation for Brie but also empowers enthusiasts to experiment with cheesemaking or select the finest examples at market.

Converting Quarts to Pounds: How Much Cheese is 4 Quarts?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The white wrapping on Brie cheese is a soft, edible rind made of mold, specifically *Penicillium camemberti*, which is cultivated during the aging process.

Yes, the white rind on Brie cheese is safe to eat and is often consumed along with the cheese, adding flavor and texture.

The white wrapping is a natural mold that forms during aging, which helps protect the cheese, develop its flavor, and give it a creamy texture.

While you can remove the rind if preferred, it is traditionally eaten with the cheese as it contributes to the overall taste and experience.

The white rind helps preserve the cheese by protecting it from bacteria and moisture loss, but proper storage (refrigerated and wrapped) is still essential to maintain freshness.