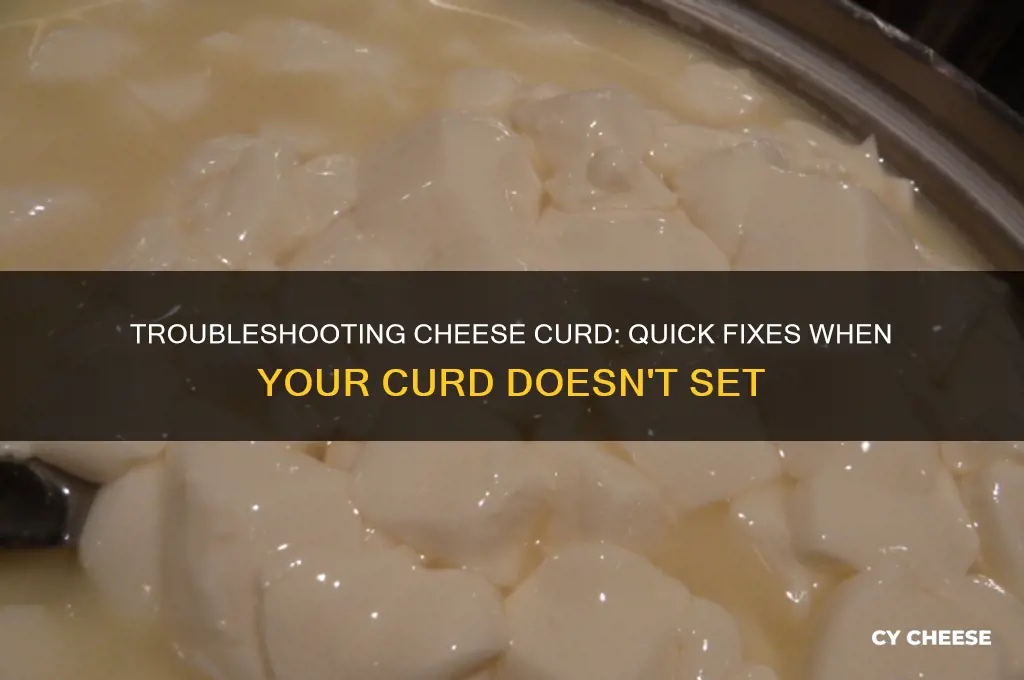

If your cheese curd fails to set, it can be frustrating, but there are several troubleshooting steps you can take to identify and address the issue. Common causes include insufficient acidity, improper rennet application, or incorrect temperature control during the cheesemaking process. First, check the pH level of your milk; if it’s too high, the curd won’t firm up properly. Ensure you’re using the right amount of rennet and that it’s evenly distributed. Temperature is also critical—milk that’s too cold or too hot can prevent curd formation. If the curd remains soft, you can try gently heating the mixture slightly or adding a bit more rennet, but be cautious not to overcorrect. Understanding these factors and adjusting your technique can help salvage your cheese and improve future batches.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Check Milk Quality | Ensure milk is fresh, not ultra-pasteurized, and free from additives. |

| Verify Acid Level | Test pH; curds may not set if acidity is too low (ideal pH: 6.4–6.6). |

| Adjust Rennet Quantity | Use proper rennet amount (1/4–1/2 tsp per gallon of milk). |

| Confirm Rennet Freshness | Replace expired rennet; it loses potency over time. |

| Maintain Temperature | Keep milk at optimal temperature (86–100°F/30–38°C) during setting. |

| Stir Gently | Avoid over-stirring, which can break curds prematurely. |

| Wait Longer | Allow more time for curds to form (up to 1 hour). |

| Add More Acid | Introduce diluted vinegar or lemon juice (1 tbsp per gallon) slowly. |

| Use Calcium Chloride | Add 1/4 tsp calcium chloride per gallon if milk lacks calcium. |

| Rehydrate Cultured Milk | Mix 1/4 cup cultured buttermilk per gallon to boost acidity. |

| Avoid Contamination | Ensure utensils and equipment are sanitized to prevent failure. |

| Experiment with Culturing Time | Extend culturing time by 15–30 minutes before adding rennet. |

| Discard and Restart | If curds still don’t set, discard batch and troubleshoot root cause. |

Explore related products

$14.04 $17.49

What You'll Learn

- Check Rennet Quality: Ensure rennet is fresh and properly stored; expired or weak rennet may fail to coagulate

- Milk Temperature: Verify milk is heated to the correct temperature (86°F/30°C) for rennet activation

- Acidity Levels: Test milk pH; too high acidity can prevent curd formation—add less starter culture next time

- Stirring Technique: Avoid over-stirring after adding rennet; gentle stirring ensures proper curd development

- Waiting Time: Be patient; curds may take up to 1 hour to set—cover and avoid disturbing

Check Rennet Quality: Ensure rennet is fresh and properly stored; expired or weak rennet may fail to coagulate

Rennet is the unsung hero of cheese making, responsible for transforming milk into curds and whey. Yet, its effectiveness hinges on freshness and storage. Expired or improperly stored rennet loses its coagulating power, leaving you with a milky mess instead of firm curds. Always check the expiration date and store rennet in a cool, dark place, ideally in the refrigerator, to maintain its potency. If your rennet is past its prime, replace it immediately—no amount of troubleshooting will salvage its efficacy.

The strength of rennet is just as critical as its freshness. Over time, even unopened rennet can degrade, especially if exposed to heat or light. To test its potency, perform a simple trial: add a small amount of rennet to a cup of warm milk and observe the coagulation time. Fresh rennet should set milk within 10–15 minutes at the recommended dosage, typically 1/4 teaspoon per gallon of milk. If the milk remains liquid or takes significantly longer to set, your rennet is likely weak and should be discarded.

Proper storage is equally vital. Rennet is sensitive to temperature fluctuations, which can denature its enzymes. Store liquid rennet in the refrigerator at 35–40°F (2–4°C), ensuring the cap is tightly sealed to prevent moisture ingress. For powdered rennet, use an airtight container and keep it in the freezer to extend its shelf life. Label containers with the purchase date to track freshness, and avoid exposing rennet to direct sunlight or warm environments, such as above the stove or near the oven.

If you suspect weak rennet is the culprit, adjust your dosage cautiously. Increasing the amount can compensate for reduced potency, but too much rennet can lead to bitter flavors or overly firm curds. Start by adding 25% more than the recipe calls for, then monitor the coagulation process closely. However, this is a temporary solution—always prioritize using fresh, high-quality rennet for consistent results. When in doubt, invest in a new batch from a reputable supplier to ensure your cheese curds set perfectly every time.

Sheep's Milk Cheese: A Casein-Sensitive Friendly Alternative?

You may want to see also

Milk Temperature: Verify milk is heated to the correct temperature (86°F/30°C) for rennet activation

The precise temperature of milk is a critical factor in cheese making, particularly when it comes to rennet activation. At 86°F (30°C), the rennet enzyme, chymosin, begins to coagulate milk proteins effectively, initiating the curdling process. Even a slight deviation from this temperature can hinder the enzyme's activity, resulting in a failure to set the curd. For instance, milk heated above 90°F (32°C) may denature the enzyme, rendering it inactive, while milk below 80°F (27°C) may slow the coagulation process significantly.

To ensure the milk reaches the optimal temperature, use a reliable dairy thermometer, preferably one with a clip to attach to the side of the pot. Heat the milk slowly, stirring occasionally to distribute the heat evenly. Avoid using high heat, as this can create hot spots and scorch the milk, affecting its protein structure. A gentle heat source, such as a double boiler or a low-wattage heating element, is ideal for maintaining precise temperature control.

Consider the type of milk being used, as its initial temperature and fat content can influence the heating process. Raw milk, for example, should be heated more cautiously to preserve its natural enzymes and bacteria. On the other hand, pasteurized milk may require a slightly longer heating time to reach the desired temperature. Additionally, the fat content of the milk can affect heat distribution; higher fat milks may heat more slowly and unevenly. Adjust the heating time and method accordingly to accommodate these variables.

In the event that the milk temperature is incorrect, take immediate corrective action. If the milk is too hot, remove it from the heat source and allow it to cool to the target temperature before adding rennet. If the milk is too cold, reheat it gradually, monitoring the temperature closely to avoid overshooting the mark. Remember, the goal is to create an environment conducive to rennet activation, and precise temperature control is key to achieving this. By mastering this aspect of cheese making, you'll be one step closer to producing a successful curd.

A practical tip for beginners is to prepare a water bath at the target temperature (86°F/30°C) before heating the milk. This allows for a more controlled and gradual heating process, reducing the risk of temperature fluctuations. Place the pot of milk in the water bath and monitor the temperature, adjusting the heat source as needed. This method, although time-consuming, provides an added layer of precision and can be particularly useful when working with sensitive milk types or in environments with fluctuating ambient temperatures. By prioritizing temperature control, you'll increase the likelihood of a successful curd set and, ultimately, a high-quality cheese.

Preserve Freshness: Freezing Sliced Deli Cheese with Freezer Paper Tips

You may want to see also

Acidity Levels: Test milk pH; too high acidity can prevent curd formation—add less starter culture next time

Milk pH is a critical factor in cheese making, often overlooked until curd formation fails. A pH level that’s too high indicates excessive acidity, which can disrupt the coagulation process and leave you with a soupy mess instead of a firm curd. Testing milk pH before adding starter culture is a simple yet effective preventive measure. Use a pH meter or test strips calibrated for dairy; ideal pH ranges vary by cheese type but generally fall between 6.6 and 6.8 for fresh milk. If the pH is below 6.4, acidity is likely too high, and curd formation will suffer.

Addressing high acidity starts with adjusting your starter culture dosage. Starter cultures, which introduce lactic acid bacteria, are essential for curd development but can overshoot acidity if overused. For most cheeses, reduce the starter culture by 10–20% in your next batch. For example, if you typically use 1 packet (2.5 grams) per gallon of milk, try 2 grams instead. Monitor pH during fermentation; if acidity rises too quickly, slow the process by lowering the temperature slightly, as cooler conditions inhibit bacterial activity.

Comparing this issue to other curd-setting problems highlights its uniqueness. While rennet deficiency or improper milk temperature can also prevent curd formation, high acidity is often a cumulative issue tied to starter culture management. Unlike rennet, which acts immediately, starter cultures work over time, making their impact harder to detect until it’s too late. This makes proactive pH testing and dosage adjustments a more reliable strategy than reactive troubleshooting.

In practice, consider the milk source and age, as these influence baseline acidity. Raw milk, for instance, may have higher natural acidity due to bacterial activity during storage. If using aged milk, test pH immediately and dilute with fresh milk if necessary. For consistent results, standardize your process: use milk within 24–48 hours of milking, maintain a clean workspace to avoid contamination, and record pH readings for each batch to identify trends. With these steps, you’ll not only diagnose high acidity but also prevent it from sabotaging your cheese curds again.

Dutch Meadows A2 Milk and Cheese Products Availability Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Stirring Technique: Avoid over-stirring after adding rennet; gentle stirring ensures proper curd development

Over-stirring after adding rennet can disrupt the delicate process of curd formation, leading to a cheese that fails to set properly. Rennet, a complex of enzymes, works by coagulating milk proteins into a solid mass. Vigorous stirring can break the fragile protein matrix, preventing it from forming a cohesive curd. This results in a weak, grainy texture or, worse, a complete failure to set. Understanding the role of stirring in this process is crucial for any cheesemaker aiming for a successful batch.

The technique of stirring after adding rennet is more art than science. Begin by gently stirring the milk in an up-and-down motion for about 30 seconds to distribute the rennet evenly. This ensures that the enzymes come into contact with the milk proteins uniformly. After this initial stir, resist the urge to continue. The milk should be left undisturbed for 5–10 minutes, allowing the rennet to work its magic. The goal is to create an environment where the proteins can link together without interference, forming a strong curd structure.

Comparing over-stirring to under-stirring highlights the importance of balance. While over-stirring can destroy the curd, under-stirring may result in uneven coagulation, with some areas setting faster than others. The key is to strike a middle ground, ensuring the rennet is fully incorporated without disrupting the developing curd. Think of it as guiding the process rather than forcing it. Gentle, deliberate movements are your allies in achieving the desired outcome.

Practical tips can further refine your stirring technique. Use a long-handled spoon or whisk to minimize contact with the milk’s surface, reducing the risk of over-agitation. Maintain a steady, slow pace during the initial stir, avoiding sudden movements. If you’re unsure about the consistency, observe the milk’s behavior: it should start to thicken slightly within 5–10 minutes. If it remains liquid or appears uneven, reevaluate your stirring method. Patience and precision are paramount in this step, as they lay the foundation for a well-set curd.

In conclusion, mastering the stirring technique after adding rennet is essential for curd development. Avoid over-stirring by limiting your movements to a brief, gentle distribution of the rennet. Allow the milk to rest undisturbed, giving the enzymes time to work effectively. By adopting this approach, you’ll create an optimal environment for curd formation, ensuring your cheese sets properly and achieves the desired texture. Remember, in cheesemaking, less is often more.

Why Turning Off Heat When Adding Cheese is Crucial for Perfect Melting

You may want to see also

Waiting Time: Be patient; curds may take up to 1 hour to set—cover and avoid disturbing

Cheese making is a delicate balance of science and art, and one of the most critical stages is waiting for the curds to set. Impatience can lead to unnecessary intervention, often disrupting the process. Understanding the role of time in curd formation is essential for any cheese maker, whether novice or experienced. The transformation from liquid milk to solid curds is not instantaneous; it requires patience and a hands-off approach.

Instructively, the waiting period for curds to set can range from 20 minutes to a full hour, depending on factors like milk type, temperature, and acidity. During this time, it’s crucial to cover the container to maintain consistent heat and humidity, which aids in the coagulation process. Disturbing the mixture—whether by stirring, peeking, or moving the container—can hinder the curds’ ability to form properly. Think of it as a resting phase for the milk, where any disruption can reset the clock. For best results, set a timer and step away, resisting the urge to check prematurely.

Comparatively, rushing this stage is akin to removing a cake from the oven too early—the structure hasn’t had time to develop fully. Just as a cake needs uninterrupted heat to rise, curds need undisturbed time to coagulate. The enzymes and acids in the milk work slowly to break down proteins, a process that cannot be accelerated by human intervention. In fact, over-handling can lead to weak, crumbly curds or even a complete failure to set. This is why professional cheese makers emphasize the importance of patience, often treating this phase as sacred.

Descriptively, the setting process is a quiet, almost meditative phase in cheese making. As the curds form, the liquid whey begins to separate, creating a distinct boundary between solid and liquid. This transformation is subtle, and its success relies on creating an environment where the milk can work its magic without interruption. Covering the container with a lid or cloth not only retains heat but also protects the mixture from drafts or temperature fluctuations, which can stall the process. Imagine it as tucking the milk in for a nap—it needs warmth and stillness to rest and transform.

Practically, if you’re tempted to check on the curds, remind yourself that time is the most critical ingredient at this stage. Use this waiting period to prepare the next steps, such as gathering equipment or sterilizing tools. If an hour passes and the curds still haven’t set, assess the temperature—it should ideally be between 80°F and 90°F (27°C to 32°C) for most cheeses. Adjusting the heat slightly or adding a few drops of rennet (if appropriate) can help, but avoid overcorrecting. The takeaway is clear: patience isn’t just a virtue in cheese making—it’s a necessity.

Cheese Before or After Toppings: The Ultimate Pizza Layering Debate

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheese curd may fail to set due to insufficient rennet, low acidity, improper milk temperature, or using ultra-pasteurized milk. Ensure you’re using the correct amount of rennet, maintaining the right acidity level, and heating the milk to the recommended temperature (usually 86°F/30°C for most cheeses).

Yes, you can try adding more rennet diluted in cool, non-chlorinated water and gently stirring it into the milk. Wait 15–30 minutes to see if the curd sets. If not, the milk may be unsuitable, and you’ll need to start over with a fresh batch.

Soft or crumbly curd often results from underdeveloped acidity or cutting the curd too early. Allow the curd to acidify further by letting it rest for a few more minutes before cutting. If the issue persists, adjust your recipe to include a longer acidification period or use a different type of starter culture.