Rennet, a crucial enzyme complex in cheese making, traditionally comes from the stomach lining of young ruminant animals, such as calves, lambs, and goats. This natural source contains chymosin, an enzyme that coagulates milk, separating it into curds and whey—a fundamental step in cheese production. Historically, rennet was extracted from the fourth stomach chamber of these animals, a practice still used in artisanal and traditional cheese making. However, modern methods have introduced microbial and genetically engineered alternatives to meet demand and address ethical concerns, offering vegetarian and vegan-friendly options for cheese production.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Source | Animal (traditionally), Microbial, Plant-based, Genetically Modified (GM) |

| Animal-derived Rennet | Extracted from the fourth stomach lining of ruminant animals (e.g., calves, lambs, goats) |

| Microbial Rennet | Produced by fungi or bacteria (e.g., Mucor miehei) through fermentation |

| Plant-based Rennet | Derived from plants like fig trees, nettles, or thistles |

| GM Rennet | Produced using genetically modified microorganisms |

| Common Animals Used | Calves, lambs, goats |

| Enzyme Type | Chymosin (primary enzyme in animal rennet) |

| Vegetarian-Friendly | Microbial and plant-based rennets are suitable for vegetarians |

| Production Scale | Animal rennet is traditional but less scalable; microbial is widely used industrially |

| Cost | Animal rennet is more expensive; microbial and GM are cost-effective |

| Availability | Animal rennet is limited; microbial and GM are more readily available |

| Ethical Concerns | Animal rennet raises ethical issues due to animal slaughter |

| Flavor Impact | Animal rennet is preferred for traditional cheese flavors |

| Sustainability | Microbial and GM rennets are more sustainable due to lower resource use |

| Regulations | Labeling requirements vary by region (e.g., EU, FDA) |

| Allergenicity | Rare, but some individuals may react to microbial rennet |

Explore related products

$14.09 $17.49

What You'll Learn

- Animal Sources: Stomach lining of ruminants like cows, goats, and sheep

- Microbial Rennet: Produced by fungi or bacteria through fermentation processes

- Plant-Based Coagulants: Extracted from thistles, nettles, or other plants for vegetarian cheese

- GMO Microorganisms: Genetically engineered microbes create chymosin for modern cheese production

- Synthetic Rennet: Chemically produced enzymes mimic traditional rennet for consistent results

Animal Sources: Stomach lining of ruminants like cows, goats, and sheep

The traditional method of obtaining rennet for cheese making involves harvesting the stomach lining of young, milk-fed ruminants such as calves, kids, and lambs. This practice dates back thousands of years, rooted in the discovery that the enzymes in these animals’ fourth stomach compartment (the abomasum) could coagulate milk. The abomasum contains chymosin, a proteolytic enzyme that curdles milk by breaking down k-casein, a protein stabilizing micelles in milk. This process separates milk into curds (solids) and whey (liquid), a critical step in cheese production.

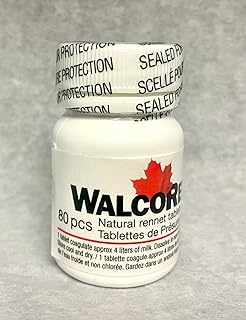

Harvesting rennet from animal sources is a precise process. The abomasum is removed post-slaughter, cleaned, and dried, then either ground into a powder or soaked in brine to extract the enzymes. For home cheesemakers, commercial animal rennet is available in liquid or tablet form, typically dosed at 1–2 drops per gallon of milk. However, the potency varies by brand, so following specific product instructions is essential. Animal rennet is highly effective, producing a clean break and firm curd, making it ideal for hard cheeses like Cheddar or Parmesan.

Ethical and dietary considerations have led to debates about animal rennet. For vegetarians, kosher, or halal diets, animal-derived rennet is often unsuitable. Additionally, the reliance on young animals raises questions about sustainability and animal welfare. Despite these concerns, animal rennet remains prized for its consistency and historical authenticity, particularly in artisanal and traditional cheese production.

A practical tip for cheesemakers using animal rennet is to dilute it in cool, non-chlorinated water before adding it to milk. This ensures even distribution and prevents overheating, which can denature the enzymes. For those experimenting with animal rennet, start with small batches to understand its behavior and adjust dosage based on milk type and desired curd texture. While alternatives exist, animal rennet’s efficiency and historical significance ensure its continued role in the art of cheese making.

Mastering Brie: Perfect Cutting Techniques for Your Cheese Board

You may want to see also

Microbial Rennet: Produced by fungi or bacteria through fermentation processes

Microbial rennet, a product of fermentation by fungi or bacteria, offers a vegetarian and often more consistent alternative to traditional animal-derived rennet. This type of rennet is produced by cultivating specific microorganisms, such as *Mucor miehei* (a fungus) or *Bacillus subtilis* (a bacterium), which secrete enzymes capable of coagulating milk. The process begins with the inoculation of a nutrient-rich medium, where the microbes are allowed to grow and produce the desired enzymes. Once the fermentation is complete, the enzymes are extracted, purified, and concentrated into a liquid or powdered form suitable for cheese making. This method not only eliminates the need for animal-derived ingredients but also provides a highly controlled and scalable production process.

For cheese makers, using microbial rennet involves precise dosage to achieve the desired curd formation. Typically, 0.05 to 0.1 milliliters of liquid microbial rennet per liter of milk is sufficient, though this can vary based on the milk’s acidity, temperature, and the specific enzyme concentration. It’s crucial to add the rennet to milk at the correct temperature (usually around 30°C or 86°F) and maintain a consistent environment to ensure proper coagulation. Unlike animal rennet, microbial varieties often work faster, reducing the overall cheese-making time. However, experimentation with dosage and timing is recommended to tailor the process to specific cheese recipes.

One of the standout advantages of microbial rennet is its suitability for vegetarian and vegan diets, as it contains no animal products. This has made it increasingly popular in the dairy industry, particularly as consumer demand for plant-based and animal-free alternatives grows. Additionally, microbial rennet is less susceptible to variability in enzyme activity compared to animal rennet, which can differ based on the animal’s diet, age, and health. This consistency ensures more predictable results in cheese production, a critical factor for commercial operations.

Despite its benefits, microbial rennet is not without limitations. Some cheese makers argue that it can impart a slightly different flavor profile compared to animal rennet, which may be undesirable for traditional or artisanal cheeses. Furthermore, certain microbial enzymes may not perform optimally in highly acidic or alkaline conditions, requiring careful monitoring of milk pH. For home cheese makers, sourcing high-quality microbial rennet can also be a challenge, as not all suppliers offer products with consistent enzyme activity.

In conclusion, microbial rennet represents a versatile and ethical solution for cheese making, particularly for those seeking vegetarian options or greater control over the production process. By understanding its production, application, and nuances, cheese makers can harness its benefits while mitigating potential drawbacks. Whether for large-scale manufacturing or small-batch experimentation, microbial rennet stands as a testament to the intersection of microbiology and culinary tradition.

Easy Cheese vs. Cheez Whiz: Unraveling the Processed Cheese Mystery

You may want to see also

Plant-Based Coagulants: Extracted from thistles, nettles, or other plants for vegetarian cheese

Traditional rennet, derived from the stomach lining of ruminant animals, has long been the standard coagulant in cheese making. However, the rise of vegetarian and vegan diets has spurred interest in plant-based alternatives. Among these, coagulants extracted from thistles, nettles, and other plants have emerged as viable options, offering a cruelty-free path to cheese production. These botanical coagulants not only align with dietary restrictions but also introduce unique flavors and textures to the final product.

Thistle rennet, for instance, is extracted from the flowers of the *Cynara cardunculus* plant, commonly known as the artichoke thistle. To use it, the flowers are soaked in water, releasing enzymes that mimic the clotting action of animal rennet. A typical dosage ranges from 10 to 20 milliliters of thistle extract per 10 liters of milk, depending on the desired firmness of the cheese. This method is particularly popular in traditional Portuguese and Spanish cheeses, such as Torta del Casar, where it imparts a slightly bitter, nutty flavor. For home cheese makers, sourcing dried thistle flowers or pre-made extracts from specialty suppliers ensures consistency and ease of use.

Nettles, another plant-based coagulant, offer a more accessible option for those with access to wild or cultivated stinging nettles (*Urtica dioica*). The leaves are boiled in water to extract enzymes, which can then be added to milk at a ratio of 1:10 (extract to milk). While nettles are less potent than thistle, their availability and simplicity make them an attractive choice for beginners. However, caution is advised when handling fresh nettles, as their hairs can cause skin irritation; wearing gloves during harvesting and preparation is essential.

Beyond thistles and nettles, other plants like fig leaves, safflower, and even pineapple have been explored for their coagulating properties. Fig leaves, for example, contain ficin, an enzyme that can curdle milk when wrapped around the container or steeped in it. This method, though traditional, requires experimentation to achieve the right balance, as excessive contact can lead to a rubbery texture. Pineapple, rich in bromelain, is more commonly used in vegan cheese recipes, where its enzymes are activated in non-dairy milks like soy or almond.

While plant-based coagulants offer ethical and creative advantages, they are not without challenges. Their enzyme activity can be less predictable than animal rennet, requiring careful monitoring of temperature and pH levels. Additionally, the flavors they impart may not suit all cheese varieties, making them better suited for specific recipes rather than universal use. Despite these limitations, their growing popularity reflects a broader shift toward sustainable and inclusive food practices. For those seeking to experiment, starting with small batches and detailed documentation of results can pave the way for successful, plant-coagulated cheeses.

Johnny Gaudreau's Ham and Cheese Ritual: Unraveling the Hockey Mystery

You may want to see also

Explore related products

GMO Microorganisms: Genetically engineered microbes create chymosin for modern cheese production

Traditional rennet, essential for curdling milk in cheese making, has long been extracted from the stomach lining of ruminant animals like calves, lambs, and goats. However, the rise of genetically engineered microorganisms has revolutionized this process, offering a more efficient, consistent, and animal-free alternative. These GMO microbes are engineered to produce chymosin, the key enzyme in rennet responsible for milk coagulation, marking a significant shift in modern cheese production.

The process begins with identifying the gene responsible for chymosin production in animal stomachs. Scientists isolate this gene and insert it into the DNA of microorganisms such as *Escherichia coli* or *Aspergillus niger*. Once modified, these microbes act as tiny factories, churning out chymosin in large quantities. This bioengineered enzyme, often referred to as fermentation-produced chymosin (FPC), is then purified and added to milk in precise dosages—typically 0.02–0.05% of the milk weight—to initiate curdling. The result is a product indistinguishable from traditional rennet in terms of functionality but with added benefits.

One of the most compelling advantages of GMO-derived chymosin is its consistency. Animal-sourced rennet varies in enzyme activity depending on the animal’s age, diet, and health, leading to unpredictable results in cheese making. In contrast, FPC offers a standardized enzyme activity, ensuring uniform curd formation and texture across batches. This reliability is particularly valuable for large-scale cheese producers who prioritize quality control. Additionally, FPC eliminates the ethical concerns associated with animal-derived rennet, making it a preferred choice for vegetarians and those seeking cruelty-free alternatives.

Despite its benefits, the adoption of GMO microorganisms in cheese production is not without challenges. Regulatory approvals vary globally, with some regions imposing strict guidelines on the use of genetically modified organisms in food production. For instance, the European Union requires extensive safety assessments and labeling for GMO-derived ingredients, while the United States has approved FPC as Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS). Cheese makers must navigate these regulations carefully to ensure compliance. Moreover, consumer perception plays a role; while some embrace the innovation, others remain skeptical of GMO technology, highlighting the need for transparent communication about the safety and benefits of FPC.

In practice, incorporating FPC into cheese making is straightforward. Cheese makers can follow standard procedures, replacing traditional rennet with the bioengineered enzyme at the recommended dosage. For artisanal producers, this transition may require experimentation to fine-tune the process, as FPC’s purity can lead to faster curdling times. However, the long-term benefits—reduced costs, ethical production, and consistent quality—make it a worthwhile investment. As technology advances, GMO microorganisms are poised to become the cornerstone of sustainable and efficient cheese production, reshaping an ancient craft for the modern era.

Perfectly Reheat Your Steak and Cheese Sub: Tips for Juicy Results

You may want to see also

Synthetic Rennet: Chemically produced enzymes mimic traditional rennet for consistent results

Rennet, a crucial component in cheese making, traditionally derives from the stomach lining of ruminant animals like calves, goats, and lambs. However, the rise of synthetic rennet has revolutionized the industry by offering a chemically produced alternative that mimics the action of natural enzymes. This innovation addresses concerns over animal welfare, supply chain inconsistencies, and the need for precise control in cheese production. Synthetic rennet, typically composed of chymosin and pepsin, is engineered to coagulate milk efficiently, ensuring uniform curd formation—a critical step in cheese making.

From a practical standpoint, using synthetic rennet involves precise dosage to achieve optimal results. Manufacturers often recommend adding 1-2 drops of liquid synthetic rennet per gallon of milk, though this can vary based on the milk’s acidity and temperature. For example, harder cheeses like cheddar may require a slightly higher dosage to achieve a firmer curd. It’s essential to dilute the rennet in cool, non-chlorinated water before adding it to the milk, ensuring even distribution. This method eliminates the variability associated with animal-derived rennet, where enzyme strength can fluctuate due to factors like animal age or diet.

One of the most compelling advantages of synthetic rennet is its consistency. Traditional rennet’s potency can vary widely, leading to unpredictable curd formation and, ultimately, inconsistent cheese quality. Synthetic rennet, on the other hand, delivers a standardized enzyme concentration, allowing cheese makers to replicate results batch after batch. This reliability is particularly valuable in commercial production, where uniformity is non-negotiable. Additionally, synthetic rennet is vegetarian-friendly, appealing to a broader consumer base and aligning with ethical and dietary preferences.

Despite its benefits, synthetic rennet is not without considerations. While it excels in functionality, some purists argue that it lacks the nuanced flavor profile associated with animal-derived rennet. However, this trade-off is often deemed acceptable for its practical advantages. For artisanal cheese makers, synthetic rennet can serve as a reliable backup when traditional sources are unavailable or inconsistent. For home cheese makers, it simplifies the process, reducing the learning curve associated with natural rennet’s variability.

In conclusion, synthetic rennet represents a significant advancement in cheese making, offering precision, consistency, and ethical alternatives to traditional methods. By understanding its application—from dosage to dilution—cheese makers can harness its benefits effectively. Whether for large-scale production or small-batch experimentation, synthetic rennet stands as a testament to how chemistry can enhance age-old culinary practices.

Cheese, My Eternal Love: A Passionate Affair with Every Bite

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Rennet traditionally comes from the fourth stomach of young ruminant animals, such as calves, lambs, or goats. The lining of this stomach contains enzymes (primarily chymosin) that curdle milk, essential for cheese making.

Yes, there are non-animal sources of rennet. These include microbial rennet (produced by fungi or bacteria), plant-based rennet (from sources like fig trees or nettles), and genetically engineered rennet (produced through biotechnology).

While animal-derived rennet is still used, especially in traditional or artisanal cheese making, many modern cheese producers opt for non-animal alternatives due to cost, availability, dietary restrictions (e.g., vegetarian or kosher/halal requirements), and ethical considerations.