The question of who owns cheese from Italy is a complex and multifaceted one, as it involves a variety of stakeholders, including traditional cheesemakers, cooperatives, large-scale producers, and even international corporations. Italy is renowned for its diverse and high-quality cheeses, such as Parmigiano-Reggiano, Mozzarella di Bufala Campana, and Gorgonzola, which are protected by geographical indications (GIs) like PDO (Protected Designation of Origin) and PGI (Protected Geographical Indication). These designations ensure that only products made in specific regions, following traditional methods, can bear these names. While many Italian cheeses are produced by small, family-run businesses or cooperatives deeply rooted in local communities, others are manufactured by larger companies or subsidiaries of multinational corporations. Additionally, the global market for Italian cheese involves distributors, retailers, and consumers worldwide, further complicating the concept of ownership. Ultimately, the essence of Italian cheese lies in its cultural heritage, craftsmanship, and regional identity, rather than in a single entity or individual.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Historical Origins of Italian Cheese Ownership

Italian cheese ownership is deeply rooted in a tapestry of regional traditions, monastic practices, and familial legacies. Unlike modern corporate structures, the historical origins of Italian cheese production are tied to local communities and religious institutions. Monasteries, for instance, played a pivotal role in preserving and advancing cheesemaking techniques during the Middle Ages. Monks, isolated from societal upheaval, meticulously documented recipes and methods, ensuring the survival of cheeses like Pecorino and Provatura. These institutions often owned the land, livestock, and knowledge, effectively becoming the custodians of Italy's dairy heritage.

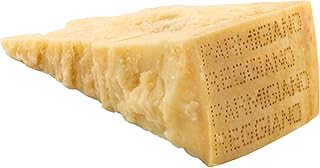

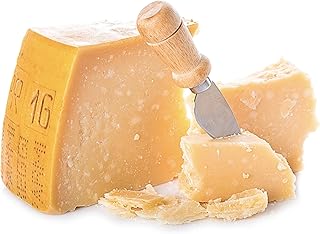

The concept of ownership evolved with the rise of feudal systems, where land and livestock were controlled by nobility. Peasants, bound to the land, produced cheese as part of their obligations, with a portion reserved for the lord. This dynamic shaped regional specialties, as local ingredients and techniques were refined under specific feudal constraints. For example, Parmigiano-Reggiano's origins trace back to the 12th century, when Benedictine monks in Emilia-Romagna perfected the art of hard cheese production. The cheese became a symbol of regional pride, with ownership tied to the collective knowledge and resources of the community rather than a single entity.

Familial ownership emerged as a dominant model in the post-feudal era, particularly in southern Italy. Families passed down cheesemaking secrets through generations, often guarding recipes as closely as heirlooms. This tradition fostered a sense of proprietary exclusivity, with certain cheeses becoming synonymous with specific families. For instance, the production of Caciocavallo Silano was historically controlled by a few families in Basilicata, who maintained strict standards to protect their reputation and market value. This familial ownership model persists today, with many small-scale producers still operating as family businesses.

The 19th and 20th centuries introduced cooperatives as a new ownership structure, democratizing cheese production. Farmers pooled resources to create collective dairies, ensuring fair distribution of profits and access to larger markets. This model revolutionized ownership, shifting from individual or familial control to shared community enterprise. Grana Padano, for example, is produced by over 150 cooperatives, each adhering to strict consortium guidelines. This approach not only preserves tradition but also empowers small producers to compete in a global market.

Modern ownership of Italian cheese is a blend of historical models, with cooperatives, families, and corporations coexisting. While large companies have acquired some brands, the essence of Italian cheese remains tied to its regional and historical roots. Ownership, in this context, is not merely legal but cultural—a stewardship of tradition passed down through centuries. Understanding this history offers insight into why Italian cheese is more than a commodity; it is a living legacy, owned collectively by those who honor its past and shape its future.

Shipping Hogshead Cheese: A Unique Culinary Journey Explored

You may want to see also

Role of Italian Regions in Cheese Production

Italy's diverse regions are the backbone of its renowned cheese production, each contributing unique flavors, techniques, and traditions. From the Alpine meadows of the north to the sun-drenched pastures of the south, regional identity is deeply embedded in every wheel, wedge, and chunk of Italian cheese. This geographical diversity is not merely a backdrop but an active ingredient, shaping the character of cheeses through local climates, grazing lands, and centuries-old practices.

Consider the role of Lombardy, home to the iconic Gorgonzola. This region’s humid climate and rich soil create ideal conditions for the Penicillium mold that gives Gorgonzola its distinctive veining. Producers here adhere to strict DOP (Protected Designation of Origin) regulations, ensuring that only milk from local cows, aged in specific Lombardian caves, can bear the Gorgonzola name. This regional exclusivity is a double-edged sword: it preserves authenticity but limits production to a select few, making Lombardy the undisputed owner of this cheese’s identity.

In contrast, the southern region of Basilicata takes a more communal approach with its Pecorino di Filiano. Shepherds here follow ancient transhumance routes, moving flocks seasonally to exploit the best grazing. This practice infuses the sheep’s milk with complex flavors, reflected in the cheese’s nutty, earthy profile. Unlike Lombardy’s centralized production, Filiano’s Pecorino is a product of collective regional effort, with small-scale producers sharing knowledge and resources. Ownership here is not about exclusivity but about shared heritage, where the region’s identity is woven into every step of production.

The comparative study of Piedmont and Sicily further illustrates regional influence. Piedmont’s Castelmagno, a DOP cheese, relies on the region’s high-altitude pastures and mixed milk (cow and sheep) to achieve its robust flavor. In Sicily, Pecorino Siciliano showcases the island’s arid climate and rugged terrain, resulting in a firmer texture and sharper taste. Both cheeses are owned by their regions in the sense that their production is inextricably linked to local geography and history, yet their ownership models differ—Piedmont leans toward controlled exclusivity, while Sicily embraces a more open, adaptive tradition.

For those looking to explore Italian cheeses, understanding regional roles is key. Start by pairing cheeses with their native wines or regional dishes to enhance flavor profiles. For instance, serve Lombardy’s Gorgonzola with a sweet Moscato d’Asti, while Sicily’s Pecorino pairs well with a bold Nero d’Avola. When sourcing, prioritize DOP labels to ensure authenticity, but don’t overlook lesser-known regional varieties—they often offer unique tastes at more accessible price points. Finally, consider the season: many Italian cheeses, like Basilicata’s Pecorino di Filiano, vary in flavor depending on the sheep’s diet, so spring and autumn batches may differ significantly. This regional awareness transforms cheese from a mere food item into a narrative of place, tradition, and ownership.

Round Cheese Blocks: Uncovering the Surprising Names Behind Circular Cheeses

You may want to see also

Family-Owned vs. Corporate Cheese Producers

Italy's cheese landscape is a battle between tradition and innovation, heritage and efficiency, family-owned and corporate producers. While both sides contribute to the country's rich dairy culture, their approaches, priorities, and outcomes differ significantly.

Consider the production process. Family-owned cheesemakers, often passed down through generations, rely on time-honored techniques, local ingredients, and small-scale operations. For instance, a family-owned Parmigiano-Reggiano producer in Emilia-Romagna might use milk from their own cows, follow a centuries-old recipe, and age the cheese in traditional wheel forms for up to 36 months. In contrast, corporate producers prioritize scalability, consistency, and cost-effectiveness. They may source milk from multiple suppliers, employ industrial production methods, and use standardized aging processes to produce cheese on a massive scale. A corporate Grana Padano producer, for example, might age their cheese for only 9-12 months to meet market demands and reduce costs.

The flavor and quality of the cheese are directly impacted by these differences. Family-owned producers often boast more complex, nuanced flavors due to their artisanal approach and attention to detail. A study by the University of Gastronomic Sciences in Italy found that cheeses from small-scale producers had significantly higher levels of volatile compounds, contributing to their unique taste profiles. Corporate producers, while consistent in quality, may sacrifice depth of flavor for efficiency. However, they can offer more affordable prices and wider distribution, making Italian cheese accessible to a global audience.

When choosing between family-owned and corporate cheese producers, consider your priorities. If you value tradition, craftsmanship, and unique flavors, seek out family-owned options. Look for certifications like DOP (Protected Designation of Origin) or visit local markets and cheesemongers to discover hidden gems. For instance, try Pecorino Romano from a small Sardinian producer, aged for 8-12 months, and pair it with a full-bodied red wine like Cannonau. On the other hand, if affordability, convenience, and consistency are key, corporate producers may be the better choice. Opt for widely available cheeses like Galbani's Mozzarella or Parmigiano-Reggiano from large-scale producers, which can be easily found in supermarkets worldwide.

Ultimately, the choice between family-owned and corporate cheese producers is a personal one, influenced by individual preferences, values, and circumstances. By understanding the differences between these two worlds, you can make informed decisions and appreciate the diversity of Italy's cheese heritage. Whether you're a connoisseur or a casual consumer, exploring the nuances of Italian cheese production can deepen your appreciation for this beloved culinary tradition.

Is Pasteurized Cheese Processed? Unraveling the Truth Behind the Label

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Government Regulations on Cheese Ownership

In Italy, the ownership of cheese is not merely a matter of who produces it but is deeply intertwined with government regulations that protect its heritage, quality, and authenticity. The Italian government, through the Ministry of Agricultural, Food, and Forestry Policies, enforces strict laws to safeguard the country’s iconic cheeses, such as Parmigiano Reggiano, Pecorino Romano, and Gorgonzola. These regulations are rooted in the Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) and Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) frameworks established by the European Union. For instance, Parmigiano Reggiano can only be produced in specific regions of Emilia-Romagna and Lombardy, using traditional methods and locally sourced milk. This ensures that the cheese’s ownership, in terms of its identity and reputation, remains tied to its geographical and cultural origins.

To comply with these regulations, producers must adhere to detailed production standards, from the type of feed given to cows to the aging process of the cheese. For example, Grana Padano, another PDO cheese, requires a minimum aging period of 9 months, while Pecorino Romano must be made exclusively from sheep’s milk. Violating these rules can result in hefty fines or the loss of certification, effectively stripping the product of its prestigious designation. These measures not only protect consumers from counterfeit products but also preserve the economic interests of legitimate producers, ensuring that ownership of the cheese’s legacy remains in the hands of those who uphold its traditions.

From a global perspective, these regulations have significant implications for international trade. Countries importing Italian cheese must recognize and enforce these PDO and PGI protections, preventing local producers from mimicking or misrepresenting Italian cheeses. For instance, a cheese labeled as "Parmesan" in the United States cannot legally bear that name unless it meets the strict criteria of Parmigiano Reggiano. This underscores how government regulations extend ownership beyond physical production to include the intellectual and cultural property embedded in these cheeses.

Practical tips for consumers and businesses navigating these regulations include verifying PDO or PGI labels on packaging and sourcing cheese from certified producers. For instance, when purchasing Prosciutto di Parma, look for the crown-shaped seal that guarantees its authenticity. Businesses exporting Italian cheese should familiarize themselves with the EU’s Geographical Indications (GI) database to avoid legal pitfalls. By understanding and respecting these regulations, stakeholders can contribute to the preservation of Italy’s cheese heritage while ensuring fair ownership and market practices.

In conclusion, government regulations on cheese ownership in Italy are a cornerstone of its culinary identity and economic stability. They protect not only the producers but also the consumers, ensuring that the cheese they enjoy is a genuine product of its region. These laws demonstrate how ownership transcends physical possession, encompassing cultural heritage, traditional methods, and global recognition. As the demand for authentic Italian cheese grows worldwide, these regulations will remain essential in safeguarding its legacy for future generations.

Cheese Lover's Dilemma: Embracing Your Passion for the Perfect Bite

You may want to see also

Export and Global Ownership of Italian Cheese

Italian cheese exports have surged by over 40% in the last decade, with Parmigiano Reggiano and Mozzarella leading the charge. This growth isn’t just about volume—it’s a testament to Italy’s strategic positioning in the global dairy market. Unlike mass-produced cheeses, Italian exports thrive on Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) status, which legally restricts production to specific regions. For instance, true Parmigiano Reggiano can only come from Parma, Reggio Emilia, Modena, Bologna, and Mantua. This exclusivity drives premium pricing and global demand, but it also raises questions about ownership. While the cheese itself is Italian, its consumption and distribution are increasingly international, blurring the lines of cultural and economic ownership.

Consider the journey of a wheel of Grana Padano from Lombardy to a gourmet shop in Tokyo. Exporters must navigate stringent EU regulations, tariffs, and local food safety standards, often partnering with international distributors. This global supply chain means ownership shifts hands multiple times—from Italian producers to exporters, then to importers and retailers abroad. For example, a U.S. importer might rebrand and repackage the cheese, adding their label while still highlighting its Italian origin. This practice, while legal, dilutes the direct ownership of Italian producers, turning their product into a global commodity.

To maintain control, some Italian cheese consortia are adopting innovative strategies. The Consorzio del Parmigiano Reggiano, for instance, has invested in blockchain technology to track each wheel’s origin and journey. This not only combats counterfeiting but also reinforces the cheese’s Italian identity in the global market. Similarly, partnerships with international chefs and influencers are being leveraged to educate consumers about authenticity. A practical tip for buyers: look for the PDO seal and batch number on the rind—this ensures you’re getting the real deal, not an imitation.

Comparatively, France’s approach to cheese export offers a contrast. While Italy focuses on protecting regional identity, France emphasizes branding and luxury. Think of Brie or Camembert—their global appeal lies in their association with French sophistication. Italy, however, leans into tradition and terroir, positioning its cheeses as irreplaceable cultural artifacts. This difference in strategy highlights Italy’s challenge: balancing global accessibility with local ownership. As demand grows, the question remains—how can Italy ensure its cheese remains distinctly Italian, even as it travels the world?

For consumers and businesses alike, understanding this dynamic is key. If you’re importing Italian cheese, prioritize direct relationships with producers or verified distributors to preserve authenticity. If you’re a producer, consider joining a consortium for collective bargaining power in international markets. The takeaway? Italian cheese is more than a product—it’s a cultural export. Its global ownership is a delicate dance between sharing heritage and safeguarding it. As the market evolves, the true measure of success will be how well Italy retains its grip on this iconic piece of its identity.

Discover the Creamy, Nutty World of A2 Cheeses: A Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Italian cheese industry is not owned by a single entity; it is a decentralized sector comprising thousands of small, medium, and large producers, including family-owned businesses, cooperatives, and corporations.

While there are larger companies like Parmareggio and Granarolo, the market is highly diverse, with many artisanal producers and regional cooperatives playing significant roles.

The Italian government does not own the cheese industry but regulates and supports it through policies, quality certifications (e.g., DOP/PDO), and agricultural subsidies.

Yes, some Italian cheese brands have been acquired by international companies, such as Lactalis (France), which owns Parmalat and other Italian dairy brands.

Traditional Italian cheeses like Parmigiano Reggiano and Mozzarella di Bufala are protected by DOP/PDO status, which is regulated by consortia of producers, not owned by any single entity.