Swiss cheese, also known as Emmental, is a medium-hard cheese that originated in Switzerland. It is known for its distinctive holes, which are called eyes in the cheese industry. The eyes are caused by a specific bacteria, Propionibacterium freudenrichii subspecies shermanii, which releases carbon dioxide gas as it feeds on lactic acid. The gas gets trapped in the cheese, forming bubbles that create the holes. The size and distribution of the holes depend on various factors, including temperature, humidity, and fermentation times. The holes in Swiss cheese contribute to its unique texture and slightly nutty flavour, making it a popular choice for sandwiches, fondue, and cheese platters.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Common name | Swiss cheese |

| Origin | Switzerland |

| Debut | 14th century |

| Region | Emmental, Switzerland |

| Milk | Cow's milk |

| Bacteria | Propionibacterium freudenrichii subspecies shermanii |

| Temperature | 70°F |

| Appearance | Round holes |

| Hole size | Dime to quarter |

| Hole formation | Carbon dioxide gas |

| Hole variation | Cheese type, moisture, fat, bacteria |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The bacterial strain Propionibacterium

Propionibacterium is a microscopic, gram-positive, non-motile bacterium that is naturally found in hay, grasses, and soil. During the cheesemaking process, these bacteria can find their way into raw milk when cows are milked, or they can be added back into pasteurized milk to ensure the formation of eyes. After the Swiss cheese is made and brined, the blocks are placed in warm rooms, which encourages the growth of Propionibacterium and the production of carbon dioxide, while also maintaining the desired consistency of the cheese.

The size and distribution of the holes in Swiss cheese are influenced by various factors during the cheesemaking process, including temperature, humidity, and fermentation times. The warmth of the aging environment, in particular, is essential to the formation of the holes, as it allows the cheese to remain soft and malleable while the bacteria grow and emit gases.

The presence of Propionibacterium not only contributes to the physical characteristics of Swiss cheese but also enhances its flavour. The bacteria are responsible for imparting Swiss cheese with its characteristic nutty flavour notes. Additionally, the holes themselves play a role in the overall taste experience, creating a light and airy texture that complements the flavour profile.

While the role of Propionibacterium in Swiss cheese hole formation is well-established, it is worth noting that other factors, such as tiny bits of hay in the milk, can also influence the size and distribution of the holes. Modern milking methods that minimize the presence of hay in the milk may contribute to the observed decrease in hole size over the years.

Emmentaler: Switzerland's Iconic Cheese Explained

You may want to see also

Carbon dioxide gas

The holes in Swiss cheese, also known as "eyes", are formed due to the production of carbon dioxide (CO2) gas during the cheese fermentation process. Propionibacterium freudenreichii, a type of bacteria used in the production of Swiss cheese, consumes lactic acid and produces carbon dioxide as a byproduct, which forms bubbles in the cheese. These CO2 bubbles get trapped in the cheese, creating the characteristic holes or "eyes" as the cheese matures.

The specific conditions of temperature and humidity during fermentation influence the size and distribution of these air pockets, resulting in the unique hole pattern of Swiss cheese. The warm temperature of around 70 degrees Fahrenheit (21 degrees Celsius) softens the cheese, making it more pliable and susceptible to the formation of holes. At this temperature, the bacteria Propionibacterium freudenrichii subspecies shermanii (P. shermanii) produce carbon dioxide gas as they grow and emit gas, creating round openings in the soft, warm cheese.

After the bubbles have formed inside the warm cheese, the cheese is then cooled to around 40°F (4°C). This temperature change helps to solidify the cheese and prevent further bacterial growth, thus preserving the formed holes. The size of the eyes can vary from small, pea-sized holes to larger ones, with the larger holes indicating a more intense and developed flavor.

The formation of eyes in Swiss cheese is a natural process that occurs due to the specific bacteria and fermentation conditions used in its production. The unique hole pattern and size variation contribute to the distinct appearance and flavor profile of Swiss cheese.

Carving Swiss Cheese Holes: Woodworking Tricks and Techniques

You may want to see also

Temperature

Swiss cheese is typically made at a warm temperature of around 70 degrees Fahrenheit (21 degrees Celsius). This temperature is essential to maintain the softness and malleability of the cheese during production. The warm temperature also provides an ideal environment for the growth of bacteria, specifically Propionibacterium freudenreichii subspecies shermanii (P. shermanii), which are added during the early stages of cheese production.

During the maturation process, Swiss cheese is aged for a minimum of two months at a relatively warm temperature. This temperature range is carefully controlled to promote the activity of the bacteria and the production of carbon dioxide gas. The warmth allows the bacteria to actively metabolize and generate gas, which accumulates and forms the characteristic eyes in the cheese.

The size of the eyes in Swiss cheese can vary, and this is also influenced by temperature. The warmth affects the rate at which the bacteria grow and produce gas, as well as the consistency of the cheese. A warmer temperature can promote faster bacterial growth and gas production, potentially resulting in larger eyes. However, the temperature must be carefully controlled to prevent the cheese from becoming too soft or runny, which could affect the structure and quality of the final product.

Additionally, the temperature during the aging process can impact the overall flavour and texture of Swiss cheese. Maintaining a suitable temperature range allows the cheese to mature properly, developing its characteristic nutty flavour and smooth texture. Deviations from the optimal temperature may result in an inferior product with undesirable characteristics. Thus, temperature control is a critical aspect of crafting Swiss cheese with its distinctive holes and sensory attributes.

Havarti and Swiss Cheese: What's the Difference?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Humidity

The holes in Swiss cheese are the result of a controlled fermentation process, influenced by factors such as the type of bacteria used, the temperature and humidity of the ageing environment, and the length of the ageing process.

The bacteria responsible for creating the holes in Swiss cheese is called Propionibacterium freudenreichii. This bacteria feeds on the lactic acid produced during the cheese-making process, releasing carbon dioxide as a byproduct. As the bacteria feed, they produce tiny bubbles of carbon dioxide that become trapped within the cheese curd. Over time, these bubbles merge into larger cavities.

The ageing process plays a crucial role in the development of Swiss cheese holes. As the cheese ages, the temperature and humidity conditions allow the bubbles to expand, creating the desired texture and the characteristic holes. The length of the ageing process also influences the size and number of holes.

The composition of the milk used in cheesemaking can also affect hole formation. Milk with higher protein content tends to produce cheese with more holes, as proteins provide a network that traps the bubbles. Additionally, the fat content of the milk can influence the texture and hole formation.

Cheesemakers have perfected the art of creating Swiss cheese with its distinctive holes through centuries of tradition and innovation. The size of the holes can vary, but the average diameter is typically around 0.5 to 1 cm. The ageing process for Swiss cheese typically takes several months to years, during which the bubbles form and expand, resulting in the familiar holes.

Swiss Cheese's Tragic End in Mother Courage

You may want to see also

Fermentation times

The holes in Swiss cheese are the result of a specific bacterium, Propionibacterium freudenrichii subspecies shermanii (P. shermanii), which produces carbon dioxide gas under certain conditions. The size and distribution of these holes are influenced by temperature, humidity, and fermentation times.

During the fermentation process, the bacteria consume lactic acid in the cheese and produce carbon dioxide as a byproduct. This gas forms air pockets within the cheese, which eventually become the holes. The specific conditions of temperature and humidity during fermentation influence the size and distribution of these air pockets, resulting in the unique hole pattern of Swiss cheese.

The ideal temperature for Swiss cheese fermentation is around 70°F (21°C). This temperature softens the cheese, making it more pliable and susceptible to the formation of holes. At this temperature, the P. shermanii bacteria produce carbon dioxide gas, creating round openings in the soft, warm cheese.

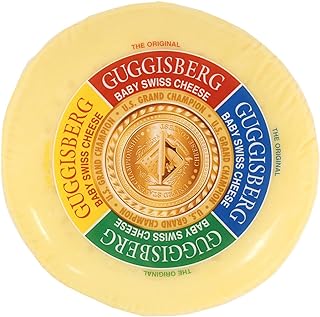

The fermentation process typically takes about four weeks for the holes to form and a total of six weeks to make Swiss cheese. The longer the fermentation process, the larger the holes in the cheese, as the cheese will have a stronger flavour. For example, an American version of Swiss cheese called Baby Swiss has smaller holes due to lesser fermentation and a milder taste.

In recent years, the holes in Swiss cheese have become smaller or non-existent due to modern milking methods, which prevent hay particles from falling into the milk and creating weak points in the curd structure where gas can form and create holes.

Crafting Swiss Cheese Cut-Outs: Easy Paper Art

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheesemakers call the holes in Swiss cheese "eyes" because they are round and resemble eyes. When holes don't appear in a batch, cheesemakers say the cheese is "blind".

The holes in Swiss cheese are caused by a special bacterial culture called Propionibacteria, or Props, that gets added to the cheese. These bacteria produce carbon dioxide, which gets trapped, forming bubbles that we call "holes".

Swiss cheese is made at a warm temperature of around 70 degrees Fahrenheit, which makes the cheese soft and malleable. As the bacteria grow, the gases they emit create round openings in the soft cheese.