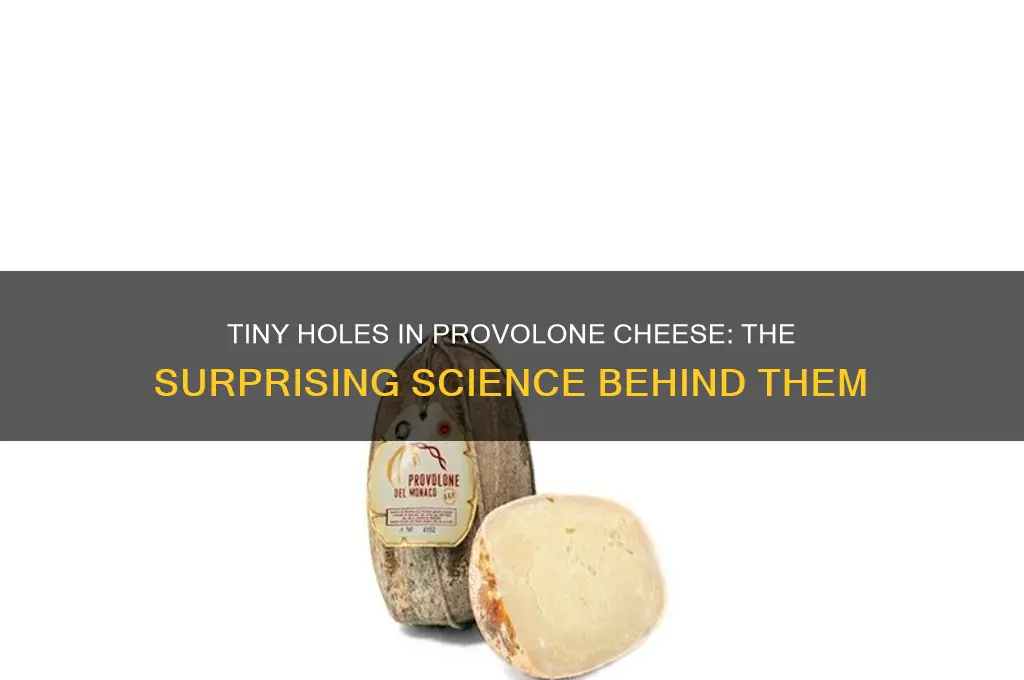

Provolone cheese, known for its distinctive flavor and texture, often features tiny holes scattered throughout its slices. These holes, technically called eyes, are a natural result of the cheese-making process. During fermentation, bacteria produce carbon dioxide gas, which becomes trapped within the curd as it solidifies. As the cheese ages, these gas pockets expand and create the characteristic holes. The size and number of eyes can vary depending on factors like the type of bacteria used, the aging process, and the specific production methods. While some may mistake these holes for imperfections, they are actually a sign of the cheese's traditional craftsmanship and contribute to its unique appearance and texture.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Cause of Holes | Result of carbon dioxide gas bubbles trapped during the cheese-making process |

| Technical Term | "Eyes" or "holes" |

| Cheese Type | Provolone, a semi-hard Italian cheese |

| Process Responsible | Starter cultures (bacteria) produce lactic acid, which lowers pH and causes gas formation |

| Gas Type | Carbon dioxide (CO2) |

| Hole Size | Typically small and evenly distributed, but can vary depending on production methods |

| Texture Impact | Contributes to provolone's characteristic texture and flavor |

| Other Cheeses with Holes | Swiss (Emmental), Gouda, and some Cheddars (though less common) |

| Production Factors Affecting Holes | Milk quality, starter culture type, curd handling, and aging conditions |

| Desired vs. Undesired | Generally considered a desirable trait in provolone, indicating proper fermentation |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Natural Aging Process: Holes form as cheese ages, due to bacteria and air exposure

- Stretching Technique: Traditional provolone making involves stretching, creating air pockets

- Bacterial Activity: Specific bacteria cultures produce gases, causing tiny holes during fermentation

- Moisture Evaporation: As cheese dries, moisture escapes, leaving behind small cavities

- Desired Texture: Holes contribute to provolone’s distinctive texture and flavor profile

Natural Aging Process: Holes form as cheese ages, due to bacteria and air exposure

The tiny holes in a provolone cheese slice are not a defect but a testament to its natural aging process. As cheese matures, bacteria play a pivotal role in transforming its texture and structure. Specifically, propionic bacteria, common in hard cheeses like provolone, produce carbon dioxide gas as they metabolize lactose. This gas becomes trapped within the cheese matrix, forming the characteristic holes known as "eyes." The size and distribution of these holes depend on factors like humidity, temperature, and aging duration, typically ranging from 3 to 12 months for provolone.

To understand this process, imagine cheese aging as a controlled fermentation. During the first few weeks, bacteria multiply rapidly, breaking down sugars and releasing gases. If the cheese is aged in a humid environment (around 90% relative humidity) at temperatures between 50°F and 60°F, the gases expand evenly, creating uniform holes. However, improper conditions—such as low humidity or fluctuating temperatures—can lead to uneven hole formation or a dense, crumbly texture. For home aging enthusiasts, maintaining consistent conditions is key to achieving the desired eye structure.

From a practical standpoint, the presence of holes in provolone is a quality indicator. Larger, evenly distributed eyes suggest a well-aged cheese with a robust flavor profile, while smaller or absent holes may indicate rushed aging or suboptimal conditions. When selecting provolone, look for slices with visible, pea-sized holes as a sign of proper maturation. For those aging cheese at home, monitor the environment closely and allow the cheese to rest undisturbed to ensure gas pockets develop naturally.

Comparatively, the aging process of provolone contrasts with that of cheeses like Swiss or cheddar. While all three develop holes due to bacterial activity, provolone’s firmer texture and lower moisture content result in fewer, smaller eyes. This distinction highlights how cheese type and aging techniques influence hole formation. By understanding these nuances, cheese lovers can better appreciate the craftsmanship behind each slice and make informed choices based on texture and flavor preferences.

In conclusion, the tiny holes in provolone are a natural byproduct of aging, driven by bacterial activity and controlled environmental conditions. They serve as both a visual cue and a flavor enhancer, marking the cheese’s journey from curd to table. Whether you’re a cheese connoisseur or a casual consumer, recognizing these holes as a sign of quality can elevate your appreciation of this timeless dairy product.

Slimming World Cheese Guide: Healthy Options for Your Diet Plan

You may want to see also

Stretching Technique: Traditional provolone making involves stretching, creating air pockets

The tiny holes in provolone cheese slices are not random imperfections but deliberate features born from a centuries-old stretching technique. This method, known as *pasta filata*, is the cornerstone of traditional provolone making. During this process, the cheese curd is immersed in hot water and stretched repeatedly, a practice that not only shapes the cheese but also incorporates air pockets. These air pockets are the precursors to the holes we see in the final product, a testament to the craftsmanship involved.

To understand the stretching technique, imagine kneading dough, but with a molten, elastic cheese curd. The curd is heated to around 165–175°F (74–80°C), a temperature that softens it enough for manipulation without causing it to break. As the cheesemaker stretches and folds the curd, air becomes trapped within its layers. This air then forms small cavities, which, when the cheese cools and sets, become the characteristic holes. The size and distribution of these holes depend on the skill of the cheesemaker and the specific stretching technique employed.

Mastering the stretching technique requires precision and practice. The curd must be stretched in a rhythmic, controlled manner to ensure even distribution of air pockets. Overstretching can lead to large, uneven holes, while insufficient stretching results in a dense, hole-free cheese. Traditional provolone makers often use a combination of hand-stretching and mechanical assistance to achieve consistency. For home enthusiasts, a simpler version of this technique can be attempted using a food-safe plastic glove filled with hot water to mimic the stretching process, though results may vary.

The air pockets created during stretching are not merely aesthetic; they influence the cheese’s texture and flavor. These holes contribute to provolone’s characteristic elasticity and slightly tangy taste by allowing for a greater surface area during aging. The holes also affect how the cheese melts, making it ideal for dishes like sandwiches or pizza, where a balance of stretchiness and structure is desired. Thus, the stretching technique is not just a step in the process but a defining feature of provolone’s identity.

In conclusion, the tiny holes in provolone cheese slices are a direct result of the traditional stretching technique, a process that combines art and science. By understanding this method, we gain a deeper appreciation for the craftsmanship behind each slice. Whether you’re a cheesemaker or a cheese enthusiast, recognizing the role of stretching in provolone’s creation adds a new layer of enjoyment to this beloved cheese.

Cheese Curds vs. Regular Cheese: Which Has Less Fat?

You may want to see also

Bacterial Activity: Specific bacteria cultures produce gases, causing tiny holes during fermentation

The tiny holes in provolone cheese, often referred to as "eyes," are not a defect but a testament to the intricate dance of bacterial activity during fermentation. Specific bacteria cultures, such as *Lactobacillus* and *Propionibacterium freudenreichii*, play a starring role in this process. These microorganisms metabolize lactose, the natural sugar in milk, and produce lactic acid as a byproduct. However, their most notable contribution is the release of carbon dioxide gas, which becomes trapped within the curd matrix, forming the characteristic holes. This phenomenon is a deliberate result of controlled fermentation, where temperature, humidity, and bacterial concentration are meticulously managed to achieve the desired texture and flavor.

To understand the mechanics, consider the fermentation environment. Provolone cheese is typically aged in a warm, humid setting, ideal for bacterial proliferation. During this phase, *Propionibacterium freudenreichii*, a slow-growing bacterium, becomes particularly active. It breaks down lactic acid further, releasing carbon dioxide and propionic acid, which contribute to the cheese’s nutty flavor. The gas bubbles expand as the cheese curds solidify, creating cavities that persist through the aging process. The size and distribution of these holes depend on factors like bacterial density (typically 1-5% of the culture mix) and fermentation duration (ranging from 3 to 12 months for provolone).

From a practical standpoint, cheesemakers can manipulate bacterial activity to control hole formation. For instance, increasing the proportion of *Propionibacterium* in the starter culture will enhance gas production, resulting in larger eyes. Conversely, reducing fermentation time or lowering the temperature can minimize hole size. Home cheesemakers experimenting with provolone should monitor humidity levels (ideally 85-90%) and maintain a consistent temperature (around 24-26°C) to encourage optimal bacterial growth. Using a pH meter to track acidity levels (aiming for a pH of 5.3-5.5) can also help ensure the bacteria thrive without overproducing gas.

Comparatively, the bacterial activity in provolone contrasts with that of cheeses like Swiss Emmental, where *Propionibacterium shermanii* is the primary gas producer. While both cheeses feature eyes, the bacterial strains and fermentation conditions differ, resulting in distinct textures and flavors. Provolone’s holes are generally smaller and more scattered, reflecting its shorter aging period and lower bacterial concentration. This comparison highlights how specific bacterial cultures and their metabolic byproducts are tailored to create unique cheese characteristics, making bacterial activity a cornerstone of artisanal cheesemaking.

In conclusion, the tiny holes in provolone cheese are a direct result of bacterial gas production during fermentation, a process both scientific and artistic. By understanding the role of specific bacteria and their environmental needs, cheesemakers can craft provolone with the perfect balance of texture and flavor. Whether you’re a professional or a hobbyist, mastering this bacterial activity is key to achieving those coveted eyes, transforming a simple cheese slice into a testament to microbial craftsmanship.

Is Babybel Cheese Coated in Beeswax? Unwrapping the Truth

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Moisture Evaporation: As cheese dries, moisture escapes, leaving behind small cavities

The tiny holes in a provolone cheese slice aren’t just a quirk—they’re a direct result of moisture evaporation during the drying process. As the cheese ages, water naturally migrates to the surface and escapes, leaving behind microscopic cavities where the moisture once resided. This phenomenon is more pronounced in harder cheeses like provolone, which have a lower moisture content to begin with. The size and distribution of these holes depend on factors like humidity, temperature, and the cheese’s density during drying. For home cheesemakers, controlling these conditions can minimize or accentuate the holes, depending on the desired texture.

To understand this process, imagine a sponge drying in the sun. As water evaporates, the sponge’s structure collapses slightly, creating visible gaps. Similarly, provolone’s protein matrix contracts as moisture escapes, trapping air in tiny pockets. This isn’t a flaw—it’s a natural part of the cheese’s transformation from a soft curd to a firm, sliceable product. Commercial producers often accelerate drying in controlled environments, ensuring consistent hole formation. For those experimenting at home, maintaining a steady temperature of 50–55°F (10–13°C) and moderate humidity (around 85%) during aging can encourage uniform evaporation and hole development.

While moisture evaporation is the primary driver of these holes, it’s not the only factor at play. The cheese’s pH level and salt content also influence how moisture is retained or released. Higher acidity can cause proteins to tighten, expelling water more rapidly, while salt acts as a preservative, slowing down the drying process. Striking the right balance is key—too much moisture, and the cheese remains soft and hole-free; too little, and it becomes brittle. For optimal results, aim for a moisture content of 35–40% in the final product, a range that allows for both structural integrity and the formation of those characteristic holes.

Practical tip: If you’re aging provolone at home, monitor the cheese’s weight weekly to track moisture loss. A 10–15% reduction in weight over 2–3 months is ideal for achieving the desired texture and hole formation. If the cheese dries too quickly, wrap it in cheesecloth or parchment paper to slow evaporation. Conversely, if it feels overly moist, increase air circulation by placing it on a drying rack. By observing these changes, you’ll gain insight into how moisture evaporation shapes the cheese’s final appearance and mouthfeel.

In the end, those tiny holes in provolone aren’t just a byproduct—they’re a testament to the cheese’s journey from fresh curd to aged delight. Embracing moisture evaporation as a natural part of this process allows you to appreciate the science behind every slice. Whether you’re a cheesemaker or a connoisseur, understanding this mechanism enhances your ability to craft or select provolone with the perfect balance of texture and flavor. So the next time you spot those holes, remember: they’re not flaws—they’re fingerprints of evaporation, telling a story of transformation and time.

Crafting the Perfect Meat and Cheese Platter: Tips and Tricks

You may want to see also

Desired Texture: Holes contribute to provolone’s distinctive texture and flavor profile

The tiny holes in provolone cheese, known as "eyes," are not merely a quirk of its appearance but a deliberate feature that significantly enhances its texture and flavor. These holes are the result of carbon dioxide gas released by bacteria during the aging process, a hallmark of provolone’s production. Unlike cheeses where holes are seen as flaws, in provolone, they are a prized characteristic that contributes to its unique mouthfeel. The eyes create a semi-firm yet slightly elastic texture, allowing the cheese to stretch and yield in a way that is both satisfying to bite into and ideal for melting. This texture is not just a sensory delight but also a functional trait, making provolone versatile in culinary applications, from sandwiches to baked dishes.

To understand the role of these holes in flavor, consider how they interact with the cheese’s structure. The eyes disrupt the dense matrix of the cheese, creating pockets that allow moisture and fat to distribute unevenly. This uneven distribution enhances the cheese’s ability to release its nutty, slightly smoky flavor when chewed. The holes also provide more surface area for the aging process to occur, deepening the cheese’s complexity over time. For optimal flavor development, provolone should be aged for at least 3–6 months, during which the holes become more pronounced and the flavor intensifies. Younger provolone, with smaller eyes, offers a milder taste and firmer texture, while older varieties with larger holes are richer and more pliable.

From a practical standpoint, the holes in provolone can be leveraged in cooking to achieve desired results. For instance, when melting provolone, the eyes allow steam to escape, preventing the cheese from becoming rubbery. This makes it an excellent choice for grilled cheese sandwiches or cheese plates where texture is key. To highlight the cheese’s unique profile, pair it with ingredients that complement its nuttiness, such as cured meats, olives, or crusty bread. For a more pronounced flavor, opt for aged provolone with larger holes, which will also provide a creamier mouthfeel when melted.

Comparatively, cheeses without these holes, like cheddar or Swiss, lack the same textural dynamism and flavor release. Swiss cheese, though also known for its holes, has a different bacterial culture and aging process, resulting in a milder taste and less elasticity. Provolone’s holes are thus not just a byproduct but a crafted feature that sets it apart. When selecting provolone, look for slices with evenly distributed eyes, as this indicates proper aging and consistent quality. Whether enjoyed on its own or as part of a dish, the holes in provolone are a testament to the artistry of cheesemaking, elevating both texture and flavor to a distinctive level.

Exploring the Names of Popular White Block Cheeses: A Tasty Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The tiny holes in provolone cheese, known as "eyes," are a natural result of the cheese-making process. They form when bacteria produce carbon dioxide gas during fermentation, creating air pockets in the cheese.

No, the holes in provolone cheese are not a sign of spoilage. They are a characteristic feature of the cheese and indicate proper fermentation during production.

Not all provolone cheeses have the same number or size of holes. The presence and size of holes depend on factors like aging time, bacteria activity, and production techniques.

The holes themselves do not significantly affect the taste or texture of provolone cheese. However, they are often associated with a sharper flavor and firmer texture in aged varieties.

No, the presence of holes does not impact the nutritional value of provolone cheese. The holes are purely structural and do not alter the cheese's protein, fat, or nutrient content.