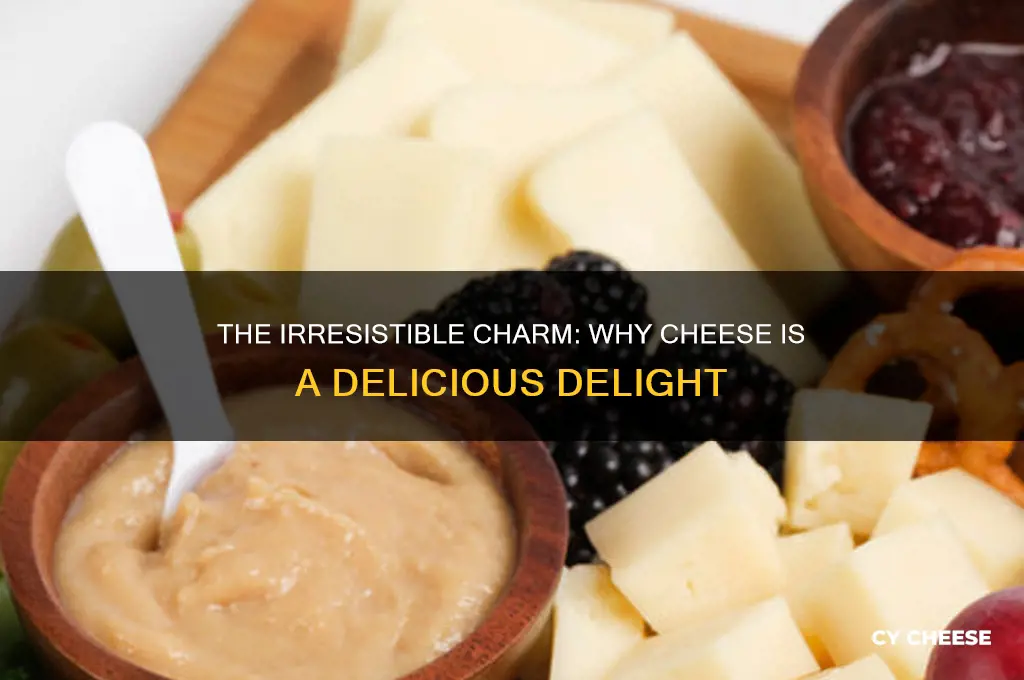

Cheese is undeniably one of the most beloved foods worldwide, celebrated for its rich flavors, creamy textures, and incredible versatility. Its yumminess stems from a complex interplay of factors, including the fermentation process that transforms milk into a savory delight, the diverse range of bacteria and molds that contribute unique tastes, and the aging process that deepens its complexity. Whether melted on a pizza, grated over pasta, or enjoyed on its own, cheese captivates the palate with its umami-packed profile, making it a staple in cuisines across cultures and a go-to comfort food for many.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Flavor Complexity | Cheese contains a wide array of flavor compounds, including peptides, amino acids, and fatty acids, which create a rich, savory (umami) taste. Aging and fermentation processes further enhance its flavor profile. |

| Fat Content | High fat content contributes to creaminess and mouthfeel, making cheese indulgent and satisfying. |

| Protein Content | Proteins in cheese break down during aging, releasing peptides that add depth and complexity to its flavor. |

| Texture Variety | Cheese ranges from soft and creamy (brie) to hard and crumbly (parmesan), offering diverse sensory experiences. |

| Umami Factor | Cheese is rich in glutamates, the compounds responsible for the savory "umami" taste, which is highly pleasurable to the palate. |

| Aroma | Volatile compounds produced during fermentation and aging give cheese its distinctive, appetizing smell. |

| Saltiness | Salt is often added during cheese production, enhancing flavor and preserving the cheese, making it more addictive. |

| Versatility | Cheese can be enjoyed on its own, melted, grated, or paired with other foods, increasing its appeal. |

| Cultural Significance | Cheese is deeply rooted in many cultures, often associated with comfort, tradition, and celebration. |

| Nutritional Value | Cheese is a good source of calcium, vitamin B12, and phosphorus, adding to its perceived value as a food. |

| Psychological Satisfaction | The combination of fat, salt, and umami triggers pleasure centers in the brain, making cheese highly rewarding. |

Explore related products

$166.37 $200

$289.75 $305

What You'll Learn

- Fat Content & Flavor: Higher fat cheeses melt better, enhancing creaminess and rich, savory taste

- Aging Process: Longer aging intensifies flavors, creating complex, nutty, or sharp profiles

- Microbial Magic: Bacteria and molds add unique tanginess, umami, and depth to cheese

- Texture Variety: From creamy Brie to crunchy Parmesan, texture amplifies sensory enjoyment

- Umami Factor: Cheese is packed with glutamates, triggering satisfying savory taste receptors

Fat Content & Flavor: Higher fat cheeses melt better, enhancing creaminess and rich, savory taste

Cheese's allure often hinges on its meltability, a quality directly tied to fat content. Higher fat cheeses, like Gruyère (typically 30-35% milkfat) or Cheddar (around 30-40% milkfat), possess a unique ability to transform from solid to silky smoothness when heated. This isn't just a textural change; it's a flavor explosion. As fat melts, it releases trapped fat-soluble flavor compounds, intensifying the cheese's inherent savory notes. Think of it as unlocking a hidden dimension of taste, where the richness of butter meets the complexity of aged dairy.

Example: Imagine a grilled cheese sandwich. A low-fat cheese might leave you with a dry, rubbery experience. But a high-fat cheese, like a sharp Cheddar, melts into a gooey, decadent delight, coating your palate with a symphony of umami and creaminess.

This meltability isn't just about indulgence; it's a culinary tool. Chefs leverage high-fat cheeses to create sauces, fondues, and gratins where a smooth, velvety texture is paramount. The fat acts as a natural emulsifier, binding ingredients together and creating a luxurious mouthfeel. Analysis: The science behind this lies in the structure of fat molecules. In high-fat cheeses, these molecules are more densely packed, allowing them to flow and intertwine when heated, resulting in that coveted melt.

Takeaway: For maximum flavor and textural impact, opt for cheeses with a milkfat content above 30% when melting is desired.

However, it's not just about melting. Fat content also influences the overall flavor profile. Higher fat cheeses tend to have a richer, more complex taste due to the increased presence of fat-soluble flavor compounds. These compounds, often derived from the milk's source (cow, goat, sheep) and aging process, contribute to the cheese's unique character. Comparative: A young, low-fat goat cheese might offer a fresh, tangy brightness, while an aged, high-fat Gouda will deliver a deep, nutty, caramelized flavor.

Practical Tip: When pairing cheeses with wine or other beverages, consider the fat content. Higher fat cheeses can stand up to bolder, more full-bodied wines, while lower fat cheeses pair well with lighter, more delicate options.

Ultimately, the relationship between fat content and flavor in cheese is a delicate dance. It's not about simply choosing the highest fat option; it's about understanding how fat contributes to the overall sensory experience. From meltability to flavor complexity, fat plays a starring role in making cheese the irresistible delight it is. Conclusion: By appreciating the role of fat, you can make informed choices, elevating your cheese experiences from ordinary to extraordinary.

Mastering Hard Cheese Storage: Tips for Longevity and Flavor Preservation

You may want to see also

Aging Process: Longer aging intensifies flavors, creating complex, nutty, or sharp profiles

Time transforms cheese from a simple dairy product into a culinary masterpiece, and the aging process is the alchemist behind this flavor evolution. Imagine a wheel of cheese as a canvas, where each passing day adds a new layer of complexity, depth, and character. This is the magic of aging, a deliberate dance between time, microbes, and moisture that intensifies flavors, creating profiles that range from nutty and earthy to sharp and tangy.

The science is fascinating: as cheese ages, moisture evaporates, concentrating the proteins and fats. This concentration amplifies the natural flavors present in the milk, while enzymes and bacteria continue to break down proteins and fats, releasing new flavor compounds. Think of it as a slow-motion symphony, where each instrument (or flavor molecule) gradually joins the orchestra, building towards a richer, more harmonious finale.

For the curious cheese enthusiast, understanding aging times is key to unlocking these flavor profiles. Young cheeses, aged for a mere few weeks, retain a mild, milky sweetness. Think fresh mozzarella or young cheddar. As aging progresses, typically from 3 to 6 months, flavors become more pronounced, developing nutty notes in Gruyère or a slight tang in Gouda. The true flavor explosions occur in cheeses aged for a year or more. Parmigiano-Reggiano, aged for a minimum of 12 months, boasts a complex symphony of nutty, savory, and slightly sweet flavors. Aged cheddar, after 2 years or more, transforms into a sharp, crumbly delight with a pungent kick.

Some cheeses, like the legendary Comté, can be aged for up to 24 months, resulting in a deeply complex flavor profile with hints of dried fruit, caramel, and even a whisper of brothy umami. This extended aging requires precise control of temperature and humidity, a testament to the cheesemaker's art.

To truly appreciate the impact of aging, conduct your own tasting experiment. Gather cheeses of the same type but with varying aging times. Start with the youngest, noting its texture and flavor. Progress to older versions, observing how the flavors intensify and evolve. This sensory journey will illuminate the transformative power of time on cheese, revealing why longer aging often equates to a more profound and satisfying culinary experience. Remember, when it comes to cheese, patience is a virtue, and the reward is a flavor explosion waiting to be savored.

Mastering Fresco Cheese: Simple Techniques to Crumble It Perfectly

You may want to see also

Microbial Magic: Bacteria and molds add unique tanginess, umami, and depth to cheese

Cheese owes much of its irresistible allure to the microscopic maestros behind the scenes: bacteria and molds. These tiny organisms are the unsung heroes of cheesemaking, transforming humble milk into a symphony of flavors. Take, for example, the tangy sharpness of a well-aged cheddar or the earthy complexity of a blue cheese like Roquefort. Both are the result of specific microbial activity. *Penicillium roqueforti*, the mold responsible for blue cheese, produces enzymes that break down fats and proteins, releasing compounds like methyl ketones, which give it that distinctive pungency. Similarly, lactic acid bacteria in cheddar convert lactose into lactic acid, creating its signature tanginess. Without these microbes, cheese would be little more than coagulated milk—a far cry from the flavorful masterpiece we know and love.

To truly appreciate the microbial magic at play, consider the role of fermentation in developing umami—that savory fifth taste that makes cheese so satisfying. Bacteria like *Lactobacillus* and *Propionibacterium* (found in Swiss cheese) produce amino acids such as glutamate, a key umami compound. In fact, aged cheeses like Parmigiano-Reggiano contain up to 1,200 milligrams of glutamate per 100 grams, rivaling the umami levels in soy sauce or cured meats. This natural process not only enhances flavor but also improves digestibility, as microbes break down complex milk proteins into smaller peptides. For home cheesemakers, understanding this science is crucial: controlling temperature, humidity, and microbial cultures can elevate a basic cheese into a gourmet experience.

While bacteria and molds are essential, their role is a delicate balance. Too much microbial activity can lead to off-flavors or spoilage, while too little results in blandness. For instance, the white rind of Brie is formed by *Penicillium camemberti*, which imparts a creamy texture and nutty flavor when allowed to grow under precise conditions (around 12°C and 90% humidity). However, if the environment is too warm or dry, the mold may produce ammonia-like compounds, ruining the cheese. Practical tip: when aging cheese at home, monitor the rind regularly and adjust conditions as needed. A hygrometer and thermometer are invaluable tools for maintaining the ideal microbial environment.

Comparing cheeses highlights the diversity of microbial contributions. Fresh cheeses like mozzarella rely on minimal bacterial activity, preserving the milk’s natural sweetness. In contrast, washed-rind cheeses like Époisses are bathed in brine or alcohol to encourage the growth of *Brevibacterium linens*, which gives them a bold, funky aroma and sticky orange rind. This bacterium is also found on human skin, contributing to body odor—a fun (if slightly off-putting) fact that underscores the biological connection between cheese and its makers. Such comparisons reveal how different microbes and techniques can produce wildly distinct flavors from the same base ingredient.

In conclusion, the magic of cheese lies in its microbial alchemy. By harnessing the power of bacteria and molds, cheesemakers unlock a world of tanginess, umami, and depth that elevates cheese from a simple food to a culinary art form. Whether you’re a connoisseur or a novice, understanding this process deepens your appreciation for every bite. So next time you savor a slice of cheese, remember: it’s not just milk—it’s a masterpiece of microbial collaboration.

Cheese Transformations: Identifying Non-Physical Changes in Dairy Evolution

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$15.95 $19.99

Texture Variety: From creamy Brie to crunchy Parmesan, texture amplifies sensory enjoyment

Cheese captivates the palate not just through taste, but through its astonishing textural diversity. Consider the contrast between a velvety wheel of Brie and a shard of crystalline Parmesan. One melts luxuriously on the tongue, while the other demands a satisfying crunch. This spectrum of mouthfeel transforms cheese from a mere ingredient into a multisensory experience, elevating everything from a simple cracker to a gourmet platter.

To fully appreciate this textural symphony, approach cheese tasting as a deliberate practice. Start with a soft-ripened cheese like Camembert, noting how its creamy interior yields effortlessly, coating the mouth in rich, buttery smoothness. Progress to semi-soft varieties like Gouda, where a slight springiness adds a playful resistance. Finally, introduce a hard, aged cheese like Pecorino Romano, its granular texture demanding slow, deliberate chewing that releases complex, savory notes. This progression highlights how texture modulates flavor release, making each bite a discovery.

For those crafting cheese boards, texture should be as strategic as flavor pairing. Balance is key: offset the gooey decadence of a triple crème with the brittle snap of a cheddar or the fudgy density of a young Manchego. Incorporate textural surprises like the crumbly tang of feta or the silky stretch of mozzarella to keep the palate engaged. Aim for a rhythm—soft, firm, crunchy—that mirrors a well-composed meal, ensuring no single sensation dominates.

Parents and educators can leverage cheese’s textural variety to encourage adventurous eating in children. Introduce mild, smooth cheeses like fresh mozzarella or young cheddar to build familiarity, then gradually incorporate more complex textures like the open, airy pores of Emmental or the sticky-chewy pull of halloumi. Pairing texture with temperature—warm, melted Gruyère versus chilled, firm Edam—adds another layer of exploration, making cheese a dynamic tool for sensory education.

Ultimately, texture in cheese is not incidental—it’s intentional. Cheesemakers manipulate moisture content, aging time, and curd treatment to craft specific mouthfeels, from the spreadable lushness of cream cheese to the sandy crunch of aged Gouda. By paying attention to these nuances, consumers can deepen their appreciation, turning a simple snack into a study of craftsmanship. Next time you savor a piece of cheese, let its texture guide you, proving that in the world of dairy, feel is just as vital as flavor.

Is Alouett Cheese Owned by Advanced Food Products? Unveiling the Truth

You may want to see also

Umami Factor: Cheese is packed with glutamates, triggering satisfying savory taste receptors

Cheese owes much of its irresistible appeal to the umami factor, a savory depth that lingers on the palate. This fifth taste, distinct from sweet, sour, salty, and bitter, is driven by glutamates—naturally occurring compounds that signal protein-rich foods to our bodies. Cheese, particularly aged varieties like Parmesan or aged Gouda, is packed with these glutamates, which bind to specific receptors on our tongue, triggering a cascade of sensory satisfaction. This biochemical reaction explains why a sprinkle of grated Parmesan can elevate a dish from ordinary to extraordinary.

To maximize the umami impact of cheese, consider the aging process. Longer-aged cheeses, such as 24-month Parmesan or 12-month cheddar, contain higher concentrations of glutamates due to protein breakdown over time. For instance, a single ounce of Parmesan delivers approximately 300 mg of glutamates, compared to 100 mg in a similar portion of fresh mozzarella. Pairing these cheeses with other umami-rich ingredients like tomatoes, mushrooms, or soy sauce amplifies the effect, creating a symphony of savory flavors. Experiment with combinations—a grilled cheese sandwich with tomato soup or a pizza topped with aged cheddar and mushrooms—to experience this synergy firsthand.

While the umami factor is a key driver of cheese’s yumminess, it’s also worth noting its psychological impact. The savory satisfaction of glutamates can evoke feelings of comfort and fullness, making cheese a go-to ingredient for indulgent meals. However, moderation is key, as excessive consumption of high-glutamate foods can lead to overstimulation of taste receptors, diminishing their sensitivity over time. Aim to incorporate cheese as a flavor enhancer rather than the main event, using smaller portions to maintain its sensory impact. For example, a modest shaving of aged Gruyère over a salad or a thin slice of blue cheese on a cracker can deliver umami richness without overwhelming the palate.

Finally, understanding the umami factor in cheese can transform how you approach cooking and pairing. For instance, when crafting a cheese board, balance high-glutamate cheeses like aged Gouda or Pecorino with milder options like fresh chèvre or young Brie. Add umami-rich accompaniments such as cured meats, olives, or caramelized onions to create a layered tasting experience. By harnessing the power of glutamates, you can elevate everyday dishes and create moments of culinary delight that linger long after the last bite.

Exploring Chee Cheese: Origins, Flavor, and Culinary Uses

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheese tastes good due to its complex combination of fats, proteins, and fermentation byproducts like lactic acid and amino acids, which create a rich, savory flavor profile.

Cheese contains casein, a protein that breaks down into casomorphins during digestion, which can trigger the brain’s opioid receptors, creating a pleasurable sensation.

Variations in milk type (cow, goat, sheep), aging time, bacteria cultures, and production methods (e.g., pasteurized vs. raw milk) contribute to the distinct flavors of different cheeses.

Cheese’s yumminess comes naturally from the fermentation process and ingredients like milk, salt, and cultures, though some processed cheeses may include additives for texture or flavor.

Cheese’s creamy texture and umami flavor complement a wide range of foods, enhancing their taste and creating a satisfying balance of flavors.