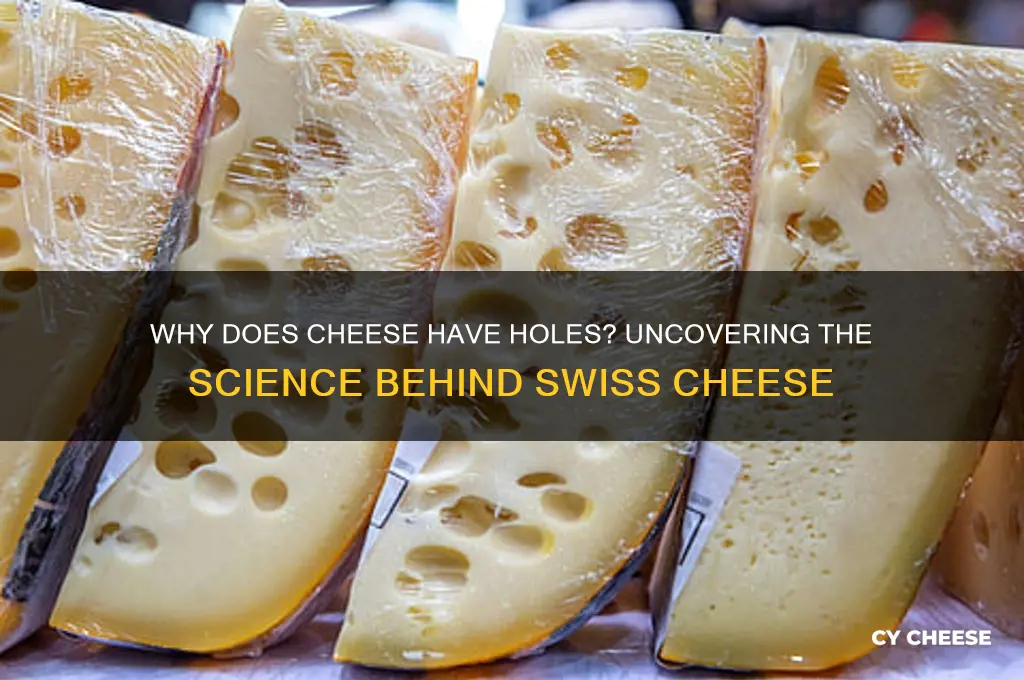

Cheese, a beloved dairy product enjoyed worldwide, often features a distinctive characteristic: holes. These holes, technically known as eyes, are most commonly associated with Swiss cheese varieties like Emmental, but they can appear in other types as well. The presence of these holes is not a flaw but rather a result of the cheese-making process, specifically the activity of bacteria. During fermentation, bacteria produce carbon dioxide gas as a byproduct, which becomes trapped within the curd, forming pockets that eventually develop into the holes we see in the final product. Understanding this process not only sheds light on the science behind cheese production but also highlights the intricate relationship between microbiology and food craftsmanship.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Cause of Holes | Carbon dioxide gas bubbles formed during fermentation by bacteria (e.g., Propionibacterium freudenreichii in Swiss cheese) |

| Cheese Types | Primarily found in Swiss-type cheeses (e.g., Emmental, Appenzeller, Gruyère) |

| Hole Size | Varies from pea-sized to larger, depending on cheese variety and aging |

| Scientific Term | "Eyes" (technical term for the holes in cheese) |

| Role of Bacteria | Propionibacterium consumes lactic acid, producing carbon dioxide and propionic acid, which creates holes |

| Impact of Milk | Holes are more prominent in cheeses made from cow's milk due to higher fat and protein content |

| Aging Process | Holes develop during the aging process as bacteria ferment and release gas |

| Texture Effect | Holes contribute to a lighter, airy texture in the cheese |

| Myth Debunked | Holes are not caused by air bubbles or mechanical processes but by bacterial activity |

| Modern Variation | Hole size and quantity can be controlled by adjusting milk treatment, bacteria cultures, and aging conditions |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Gas Formation by Bacteria: Specific bacteria produce CO2 during fermentation, creating bubbles that become holes

- Role of Starter Cultures: Starter cultures influence hole size and quantity in cheese varieties

- Effect of Milk Type: Cow, goat, or sheep milk affects hole formation due to fat and protein content

- Aging Process Impact: Longer aging increases hole size as gases expand over time

- Cheese Variety Differences: Swiss, Emmental, and Gruyère have more holes due to specific production methods

Gas Formation by Bacteria: Specific bacteria produce CO2 during fermentation, creating bubbles that become holes

Cheese holes, those delightful pockets of air, are not a sign of inferior quality but rather a testament to the intricate dance of microbiology and chemistry. At the heart of this phenomenon lies a specific group of bacteria that play a starring role in the fermentation process. These bacteria, primarily *Propionibacterium freudenreichii* in Swiss-type cheeses like Emmental and Gruyère, produce carbon dioxide (CO2) as a byproduct of their metabolic activity. As the bacteria break down lactic acid, they release CO2 gas, which becomes trapped within the curd, eventually forming the holes we associate with these cheeses.

To understand this process, imagine a microscopic factory within the cheese. The bacteria, thriving in the warm, nutrient-rich environment, consume lactate and produce propionic acid, acetic acid, and CO2. The CO2 bubbles, initially tiny and dispersed, gradually coalesce as the cheese ages. The size and distribution of these holes depend on factors like the density of the curd, the humidity of the aging environment, and the activity level of the bacteria. For instance, a higher concentration of bacteria or a longer aging period can result in larger, more numerous holes. This is why artisanal cheesemakers often carefully control the bacterial cultures and aging conditions to achieve the desired hole size and texture.

From a practical standpoint, achieving the perfect hole structure requires precision. Cheesemakers typically inoculate the milk with a specific dosage of *Propionibacterium* culture, often around 0.5–1% of the milk volume, to ensure consistent bacterial activity. The cheese is then aged at a controlled temperature (around 20–24°C) and humidity (85–95%) to encourage gas formation. A key caution is to avoid over-inoculation, as excessive bacterial activity can lead to uneven hole distribution or a crumbly texture. For home cheesemakers, using pre-measured bacterial cultures and monitoring the aging environment with a hygrometer can help replicate these conditions successfully.

Comparatively, cheeses without these specific bacteria, such as Cheddar or Mozzarella, lack the characteristic holes because their fermentation processes do not produce significant amounts of CO2. This highlights the unique role of *Propionibacterium* in creating the iconic texture of Swiss-type cheeses. While some may prefer the smooth consistency of hole-less cheeses, the presence of holes in others is a mark of craftsmanship and tradition, showcasing the interplay between science and art in cheesemaking.

In conclusion, the holes in cheese are not random but the result of a carefully orchestrated biological process. By understanding the role of gas-producing bacteria, cheesemakers can manipulate this process to create cheeses with specific textures and appearances. Whether you're a professional or a hobbyist, mastering this aspect of fermentation opens up new possibilities for crafting cheeses that are as scientifically fascinating as they are delicious.

Snowshoeing Meets Gourmet Bliss: Wine & Cheese Pairing April 4th

You may want to see also

Role of Starter Cultures: Starter cultures influence hole size and quantity in cheese varieties

The eyes have it—or rather, the cheese does. Those distinctive holes in Swiss cheese, for instance, are not just a quirky feature but a result of complex microbial activity. Starter cultures, specifically lactic acid bacteria, play a pivotal role in this process. When added to milk, these bacteria ferment lactose into lactic acid, lowering the pH and causing the milk to curdle. But their influence doesn't stop there. Certain strains, like *Streptococcus thermophilus* and *Lactobacillus helveticus*, produce carbon dioxide (CO₂) as a byproduct of metabolism. This gas becomes trapped within the curd, forming the holes we associate with cheeses like Emmental and Gruyère. The size and quantity of these holes depend on factors such as bacterial strain, dosage, and environmental conditions during fermentation.

Consider the dosage of starter cultures as a chef’s secret ingredient. Too little, and the CO₂ production may be insufficient to create noticeable holes. Too much, and the curd could become too acidic, leading to a dense, hole-free texture. For example, in Emmental production, starter cultures are typically added at a rate of 1–2% of the milk volume. This precise measurement ensures optimal gas formation without compromising the cheese’s structure. Manufacturers often experiment with different strains to achieve specific hole characteristics, such as larger eyes in traditional Swiss cheese or smaller, more uniform holes in modern varieties.

The aging process further amplifies the role of starter cultures. As cheese matures, the trapped CO₂ expands, enlarging the holes. However, this process is not uniform across all cheese varieties. For instance, in younger cheeses like young Gouda, the holes are barely visible because the aging period is shorter, and the CO₂ has less time to create significant voids. In contrast, a 12-month-aged Gruyère will exhibit larger, more pronounced holes due to prolonged gas expansion. Cheesemakers must therefore balance starter culture selection with aging time to achieve the desired hole profile.

Practical tips for home cheesemakers: if you’re aiming for a holey cheese, choose starter cultures known for high CO₂ production, such as *Lactobacillus helveticus*. Maintain a consistent temperature of 20–24°C (68–75°F) during fermentation to encourage bacterial activity. After pressing, ensure the cheese is aged in a humid environment (85–90% humidity) to allow for proper gas expansion. Regularly flip the cheese to distribute moisture evenly, preventing uneven hole formation. By understanding and manipulating these variables, you can control the size and quantity of holes, turning a simple block of curd into a masterpiece of microbial artistry.

Jalapeno Cheese Bread Storage: Refrigerate or Room Temp?

You may want to see also

Effect of Milk Type: Cow, goat, or sheep milk affects hole formation due to fat and protein content

The type of milk used in cheesemaking is a critical factor in determining the presence and size of holes, known as "eyes," in the final product. Cow, goat, and sheep milk each bring unique fat and protein profiles to the table, influencing the activity of gas-producing bacteria and the overall structure of the cheese. For instance, cow’s milk, with its higher fat content (typically 3.5–4% in whole milk), tends to produce larger, more consistent holes in cheeses like Swiss Emmental. This is because the higher fat content creates a more pliable curd, allowing carbon dioxide gas to expand and form visible pockets.

To understand the mechanics, consider the role of protein content. Sheep’s milk, with its higher protein levels (around 5.5–6.5%), often results in denser cheeses with fewer or smaller holes. The tighter protein matrix restricts gas expansion, as seen in Manchego. Conversely, goat’s milk, with lower fat (3–4%) and moderate protein (3.5–4%), produces cheeses like Chevre with minimal to no holes due to a less elastic curd structure. For home cheesemakers, experimenting with milk types can yield dramatic differences: using 100% sheep’s milk in a Swiss-style recipe will likely reduce hole size by 30–40% compared to cow’s milk.

A practical tip for controlling hole formation is to adjust milk blends. Mixing 70% cow’s milk with 30% goat’s milk can moderate fat content, resulting in medium-sized holes ideal for semi-hard cheeses. However, caution is advised: excessive fat reduction (below 2.5%) can inhibit hole formation entirely, while high protein levels (above 6%) may lead to a crumbly texture unsuitable for eye development. Always monitor curd elasticity during the cutting phase—a firm but flexible curd is key to successful hole formation.

From a comparative standpoint, the fat-to-protein ratio is the linchpin. Cow’s milk’s 4:1 fat-to-protein ratio creates an optimal environment for gas retention, while sheep’s milk’s 1:1 ratio stifles it. Goat’s milk, with its 1.2:1 ratio, falls in between but leans toward hole suppression. For those seeking precision, using milk with standardized fat content (e.g., 3.5% fat cow’s milk) ensures consistency in hole size. Pairing this with controlled fermentation temperatures (20–22°C) maximizes bacterial activity, amplifying hole formation in fat-rich milks.

In conclusion, milk type dictates hole formation through its fat and protein interplay. Cow’s milk excels in creating large, uniform holes, sheep’s milk minimizes them, and goat’s milk often eliminates them. By manipulating milk blends and understanding their compositional effects, cheesemakers can tailor hole characteristics to specific styles. Whether crafting a hole-filled Emmental or a dense Manchego, the milk’s fat and protein content remains the silent architect of cheese texture.

Does Cheese Contain BCM-7? Unraveling the Truth About This Protein

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Aging Process Impact: Longer aging increases hole size as gases expand over time

The size of holes in cheese isn’t arbitrary—it’s a direct result of the aging process. As cheese matures, gases produced by bacteria expand, pushing against the curd matrix and creating larger voids. This phenomenon is most pronounced in semi-hard to hard cheeses like Emmental or aged Gouda, where aging times often exceed six months. Shorter-aged cheeses, such as young Cheddar (aged 2–3 months), retain smaller, more uniform holes due to less gas expansion. The relationship between aging duration and hole size is linear: the longer the cheese ages, the more pronounced the holes become.

To understand this process, consider the role of *propionic acid bacteria*, which are responsible for producing carbon dioxide gas during fermentation. In younger cheeses, this gas forms tiny bubbles trapped within a firmer, less pliable curd structure. Over time, as enzymes break down proteins and fats, the cheese softens internally, allowing these bubbles to expand. For example, Emmental aged for 12 months will exhibit holes up to 1.5 cm in diameter, whereas the same cheese aged for only 3 months will have holes no larger than 0.5 cm. This expansion is not just aesthetic—it alters texture, making older cheeses crumbly and open-textured compared to their younger, denser counterparts.

Practical considerations for cheesemakers include controlling humidity and temperature during aging to optimize gas expansion. Ideal conditions for hole development in cheeses like Emmental are 85–90% humidity and 18–22°C (64–72°F). Deviations from these parameters can result in uneven hole distribution or a dense, holeless interior. For home cheesemakers, monitoring aging time is critical: aim for a minimum of 6 months for noticeable hole formation in semi-hard cheeses. Regularly flipping the cheese and maintaining consistent environmental conditions will ensure even gas expansion and hole uniformity.

Comparatively, softer cheeses like Brie or Camembert lack significant holes because their aging process (typically 4–6 weeks) is too short for substantial gas expansion. These cheeses also have a higher moisture content, which limits the structural changes needed for hole formation. In contrast, hard cheeses like Parmesan, aged for 12–36 months, develop a granular texture with minimal holes due to a different bacterial culture and lower moisture content. Thus, the aging process’s impact on hole size is cheese-type specific, with semi-hard varieties benefiting most from prolonged aging.

The takeaway for cheese enthusiasts is clear: hole size is a marker of maturity, particularly in semi-hard cheeses. When selecting aged cheeses, larger holes indicate a longer aging period and a more complex flavor profile. For those aging cheese at home, patience is key—rushing the process will yield smaller holes and a less developed taste. By understanding the science behind hole expansion, both makers and consumers can better appreciate the craftsmanship and time invested in each wheel of cheese.

Discover Palak Paneer: India's Creamy Spinach and Cheese Delight

You may want to see also

Cheese Variety Differences: Swiss, Emmental, and Gruyère have more holes due to specific production methods

The holes in cheese, often called "eyes," are a result of gas production during the aging process. However, not all cheeses develop these holes equally. Swiss, Emmental, and Gruyère stand out for their distinctive, large eyes, a feature directly tied to their specific production methods. Understanding these techniques reveals why these varieties are more prone to hole formation compared to others.

The Role of Bacteria and Curd Treatment

Swiss, Emmental, and Gruyère cheeses owe their holes to a particular strain of bacteria, *Propionibacterium freudenreichii*. This bacterium, added during the cheesemaking process, produces carbon dioxide gas as it metabolizes lactic acid in the curd. The gas becomes trapped within the cheese, forming the characteristic holes. However, the size and number of these holes depend on how the curd is treated. For these cheeses, the curd is cut into larger pieces and heated to higher temperatures (around 45°C or 113°F) compared to other varieties. This treatment creates a more open structure in the curd, allowing the gas to expand and form larger eyes.

Aging Conditions: Time and Humidity Matter

The aging process further distinguishes these cheeses. Swiss, Emmental, and Gruyère are aged in humid environments for several months, often 4 to 12 months, depending on the desired hardness and flavor. During this time, the *Propionibacterium* continues to produce gas, and the humid conditions prevent the cheese from drying out, ensuring the holes develop fully. In contrast, cheeses like Cheddar or Gouda, which are aged in drier conditions or for shorter periods, lack the same bacterial activity and structural openness, resulting in fewer or no holes.

Practical Tips for Hole Formation

If you’re a home cheesemaker aiming for large holes, mimic the production methods of Swiss, Emmental, or Gruyère. Start by using a mesophilic starter culture that includes *Propionibacterium freudenreichii*. Heat the curd to 45°C (113°F) and cut it into large pieces (about 2–3 cm) to create space for gas expansion. After pressing, age the cheese in a humid environment (around 90% humidity) at 18–20°C (64–68°F) for at least 3 months. Regularly flip the cheese to ensure even moisture distribution and hole development.

Comparative Analysis: Why Other Cheeses Lack Holes

Cheeses like Mozzarella or Brie lack holes because their production methods suppress gas formation. Mozzarella is stretched and kneaded, expelling any gas, while Brie’s soft texture and mold-ripened aging process prevent gas pockets from forming. Even among hard cheeses, those aged in drier conditions or without *Propionibacterium* will have fewer holes. This highlights how specific bacterial cultures, curd treatment, and aging conditions collectively determine whether a cheese develops holes—and how many.

By focusing on these production methods, it becomes clear why Swiss, Emmental, and Gruyère are the poster children for holey cheese. Their unique combination of bacteria, curd handling, and aging environment creates the perfect conditions for large, evenly distributed eyes, setting them apart from other varieties.

Why Some Cheeses Pack a Punch: The Science of Sharpness

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The holes in cheese, often called "eyes," are formed by carbon dioxide gas bubbles produced by bacteria during the aging process. These bacteria, such as *Propionibacterium freudenreichii*, metabolize lactic acid and release gas, which gets trapped in the cheese curd, creating the characteristic holes.

No, only certain types of cheese, like Swiss cheese (Emmental), Gruyère, and some others, have holes. This is because they are made using specific bacteria and aging techniques that encourage gas bubble formation. Cheeses without these bacteria or processes, such as cheddar or mozzarella, do not develop holes.

Yes, the size and number of holes can be influenced by factors like the type and amount of bacteria used, the temperature and humidity during aging, and the size of the curd particles. Cheesemakers can adjust these conditions to produce cheese with larger, smaller, or fewer holes, depending on the desired outcome.