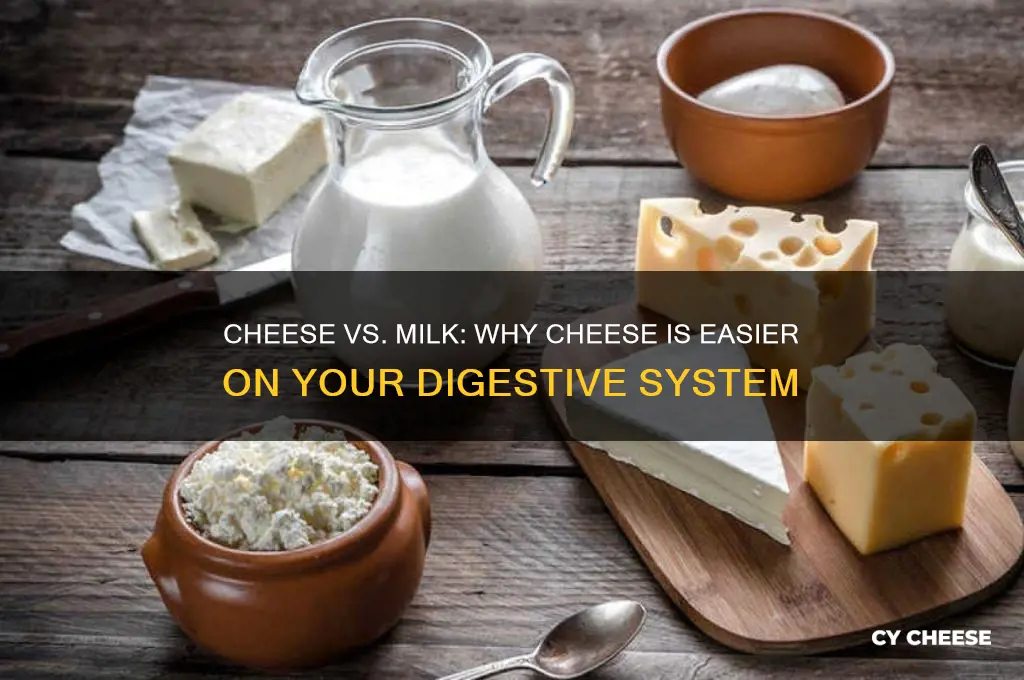

Cheese is generally easier to digest than milk due to its lower lactose content and the fermentation process involved in its production. During cheese-making, bacteria break down much of the lactose (milk sugar) into lactic acid, reducing the amount that can cause digestive discomfort, especially for those with lactose intolerance. Additionally, the curdling and aging processes remove much of the whey, which contains proteins like casein and lactose, further easing digestion. The presence of beneficial bacteria in some cheeses can also aid in gut health, making cheese a more tolerable option for many compared to drinking milk directly.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Lactose Content | Cheese has significantly lower lactose due to fermentation and aging, making it easier for lactose-intolerant individuals to digest. |

| Fat Content | Cheese contains less whey (liquid part of milk), reducing the load on the digestive system. |

| Protein Structure | Proteins in cheese are more easily digestible due to the breakdown during the cheese-making process. |

| Fermentation | Fermentation in cheese production breaks down lactose and proteins, enhancing digestibility. |

| Water Content | Cheese has lower water content compared to milk, reducing the volume of liquid in the stomach. |

| Enzyme Activity | Enzymes used in cheese-making (e.g., rennet) pre-digest milk proteins, making them easier to absorb. |

| Calcium Absorption | Cheese provides calcium in a more bioavailable form due to its lower lactose and fat content. |

| Allergen Reduction | The cheese-making process reduces milk allergens, making it more tolerable for some individuals. |

| Digestive Enzyme Requirement | Less lactase (lactose-digesting enzyme) is needed to digest cheese compared to milk. |

| Gut Microbiome Impact | Cheese promotes a healthier gut microbiome due to its fermented nature, aiding digestion. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Lactose Breakdown: Cheese has less lactose, making it easier for lactose-intolerant individuals to digest

- Fermentation Process: Fermentation reduces lactose and predigests proteins, easing digestion

- Fat Content: Cheese’s higher fat slows digestion, reducing lactose absorption issues

- Protein Structure: Fermentation alters milk proteins, making them easier to break down

- Water Removal: Less water in cheese concentrates nutrients, reducing digestive workload

Lactose Breakdown: Cheese has less lactose, making it easier for lactose-intolerant individuals to digest

Cheese, a dairy staple, often serves as a more digestible alternative to milk for those with lactose intolerance. This phenomenon hinges on the lactose content, a sugar found in milk that many struggle to break down. During cheese production, lactose is significantly reduced, offering a gentler option for sensitive digestive systems.

The Science Behind Lactose Reduction

When milk is transformed into cheese, the whey—a byproduct rich in lactose—is separated and removed. This process naturally lowers lactose levels, often to less than 2 grams per serving in hard cheeses like cheddar or Swiss. In contrast, a single cup of milk contains around 12–13 grams of lactose. For context, individuals with lactose intolerance typically tolerate up to 12 grams of lactose per sitting, making cheese a safer bet. Soft cheeses like mozzarella or brie retain slightly more lactose (3–5 grams per serving) but still fall below milk’s threshold.

Practical Tips for Lactose-Intolerant Individuals

If you’re lactose intolerant, opt for aged, hard cheeses, which have the lowest lactose content. Pairing cheese with other foods can further ease digestion by slowing lactose absorption. Start with small portions—a 30-gram serving (about the size of your thumb) is a safe starting point. Monitor your body’s response and gradually increase intake if tolerated. For those with severe intolerance, lactase enzymes (available over-the-counter) can be taken before consuming higher-lactose cheeses like cream cheese or ricotta.

Comparing Cheese and Milk: A Digestive Perspective

Milk’s high lactose content can trigger bloating, gas, and diarrhea in intolerant individuals within 30 minutes to 2 hours of consumption. Cheese, with its reduced lactose, bypasses this issue for many. For instance, a study found that 80% of lactose-intolerant participants tolerated 20 grams of hard cheese without symptoms, whereas only 20% could manage a glass of milk. This stark difference underscores cheese’s role as a dairy alternative for those seeking nutritional benefits without discomfort.

Takeaway: Cheese as a Digestive Ally

Cheese’s lower lactose content makes it a practical solution for lactose-intolerant individuals to enjoy dairy. By choosing aged, hard varieties and practicing portion control, most can incorporate cheese into their diet without adverse effects. Always listen to your body and consult a dietitian if unsure about your tolerance levels. Cheese isn’t just a flavor enhancer—it’s a digestive compromise between indulgence and health.

Easy Cauliflower Water Extraction: No Cheesecloth Required – Simple Tips

You may want to see also

Fermentation Process: Fermentation reduces lactose and predigests proteins, easing digestion

Cheese, a beloved dairy product, often sits better with those who struggle to digest milk. This phenomenon can be largely attributed to the fermentation process, a transformative journey that milk undergoes to become cheese. During fermentation, lactose—the sugar in milk that many find difficult to digest—is significantly reduced. This is because the bacteria cultures added during cheese-making consume lactose as their energy source, converting it into lactic acid. As a result, the final cheese product contains far less lactose than the original milk, making it a more comfortable option for lactose-intolerant individuals.

The benefits of fermentation extend beyond lactose reduction. Proteins in milk, which can be complex and difficult to break down, are predigested during this process. The bacteria and enzymes at work break down these proteins into smaller, more easily absorbed peptides and amino acids. This predigestion not only eases the burden on the digestive system but also enhances nutrient availability. For instance, studies show that fermented dairy products can improve the absorption of essential minerals like calcium and phosphorus, particularly in older adults whose digestive efficiency may decline with age.

To maximize the digestive benefits of cheese, consider opting for varieties with longer fermentation periods, such as aged cheddar or Parmesan. These cheeses typically have lower lactose levels and more thoroughly predigested proteins compared to softer, fresher cheeses like mozzarella or ricotta. Additionally, pairing cheese with fiber-rich foods like whole-grain crackers or fresh vegetables can further support digestion by slowing the absorption of lactose and promoting a healthy gut environment.

For those experimenting with cheese as a milk alternative, start with small portions to gauge tolerance. A 30-gram serving (about the size of a matchbox) is a good starting point. Gradually increase the amount as your digestive system adjusts. It’s also worth noting that while fermentation reduces lactose, it doesn’t eliminate it entirely. Individuals with severe lactose intolerance should still monitor their intake and consider consulting a dietitian for personalized advice.

Incorporating fermented dairy like cheese into your diet can be a practical solution for improving dairy tolerance. By understanding the science behind fermentation—how it reduces lactose and predigests proteins—you can make informed choices that support both your taste preferences and digestive health. Whether you’re crafting a charcuterie board or sprinkling grated cheese on a salad, this ancient process turns a potentially problematic food into a more accessible, nutrient-rich delight.

Should You Freeze All Cheese Sticks? Storage Tips and Tricks

You may want to see also

Fat Content: Cheese’s higher fat slows digestion, reducing lactose absorption issues

Cheese's higher fat content acts as a digestive speed bump, paradoxically easing lactose intolerance symptoms. This might seem counterintuitive – fat often gets a bad rap for slowing digestion. But in the case of lactose malabsorption, this slowdown is beneficial.

Imagine lactose as a race car zooming through your intestines. In milk, this car speeds unchecked, often reaching the colon before your body can fully break it down, leading to gas, bloating, and discomfort. Cheese, with its higher fat content, acts like a series of toll booths on the digestive highway. These fat molecules slow the overall journey, giving your body more time to produce lactase, the enzyme needed to break down lactose.

This slowing effect is particularly helpful for individuals with lactose intolerance. Studies suggest that even individuals with severe lactose intolerance can often tolerate harder, higher-fat cheeses like cheddar or Swiss. The key lies in the fat-to-lactose ratio. A 30g serving of cheddar cheese, for example, contains roughly 7g of fat and less than 0.5g of lactose, a ratio that significantly reduces the likelihood of digestive distress.

In contrast, a cup of whole milk contains around 8g of fat but a whopping 12g of lactose, a recipe for potential discomfort for those with lactose intolerance.

It's important to note that not all cheeses are created equal in this regard. Fresh cheeses like ricotta or cottage cheese, with their lower fat content, retain more lactose and may still cause issues. Opt for aged, harder cheeses with higher fat percentages for better tolerance.

Think of cheese as a more leisurely digestive experience. The fat content acts as a natural buffer, allowing your body to keep pace with lactose breakdown. This doesn't mean cheese is a cure for lactose intolerance, but it offers a delicious and often well-tolerated alternative to milk for those who struggle with dairy digestion.

Microwaving Nacho Cheese in a Jar: Safe or Risky?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$44.18 $46.84

Protein Structure: Fermentation alters milk proteins, making them easier to break down

Milk, in its raw form, contains proteins like casein and whey that can be challenging for some individuals to digest, particularly those with lactose intolerance or mild dairy sensitivities. During the fermentation process that transforms milk into cheese, bacteria and enzymes break down these proteins into smaller, more manageable fragments. This structural alteration is key to why cheese is often easier on the digestive system. For instance, the fermentation of milk into cheddar or Swiss cheese reduces the protein load, making it less likely to trigger discomfort.

Consider the role of enzymes like rennet and microbial cultures in cheese production. These agents cleave large protein molecules into peptides and amino acids, which require less effort from the body’s digestive enzymes. For example, the primary protein in milk, beta-casein, is split into smaller chains during fermentation, reducing its potential to cause inflammation or allergic reactions. This is particularly beneficial for adults over 30, who often experience a natural decline in lactase production, the enzyme needed to digest lactose.

From a practical standpoint, opting for aged cheeses like Parmesan or Gouda can further enhance digestibility. Longer aging periods allow more time for protein breakdown, resulting in a product with fewer intact proteins that might irritate the gut. For those with mild lactose intolerance, starting with small portions (1–2 ounces) of hard, aged cheeses can be a strategic way to enjoy dairy without discomfort. Pairing cheese with fiber-rich foods like apples or whole-grain crackers can also aid digestion by slowing the absorption of proteins.

While fermentation simplifies protein structures, it’s important to note that individual tolerance varies. Those with severe dairy allergies or sensitivities to specific protein fragments may still experience issues. However, for most people, the altered protein profile in cheese offers a more digestible alternative to milk. Understanding this process empowers consumers to make informed choices, turning cheese from a potential digestive hazard into a gut-friendly option.

Is Overnight Unrefrigerated Sliced American Cheese Safe to Eat?

You may want to see also

Water Removal: Less water in cheese concentrates nutrients, reducing digestive workload

Cheese contains significantly less water than milk—typically 50-60% less—due to the whey removal process during cheesemaking. This dehydration concentrates nutrients like protein, fat, and minerals, creating a denser food matrix. For digestion, this concentration matters: the body expends less energy breaking down smaller volumes of food. Think of it as the difference between sipping a gallon of milk (which requires substantial stomach acid and enzyme activity) and consuming a compact 1.5-ounce cheese serving delivering equivalent protein.

From a digestive physiology perspective, water dilution in milk necessitates greater gastric secretion to emulsify fats and denature proteins. Cheese’s lower moisture content bypasses this step, allowing digestive enzymes like lipase and pepsin to act more efficiently. Studies show that the stomach empties cheese 2-3 hours faster than an equivalent volume of milk, reducing the risk of bloating or discomfort. For individuals with mild lactose intolerance, this accelerated transit time minimizes exposure to undigested lactose, a common culprit for gas and cramping.

Consider a practical scenario: a 200ml glass of whole milk (8g protein, 8g fat) requires the stomach to process 200g of material, while 30g of cheddar cheese (7g protein, 6g fat) delivers similar macronutrients in one-sixth the weight. This disparity in water content translates to a 40-60% reduction in digestive workload, depending on cheese type. Hard cheeses like Parmesan (34% water) offer the greatest advantage, while softer varieties like mozzarella (52% water) provide moderate benefits.

To leverage this for better digestion, replace 1 cup of milk (240ml) with 1.5 ounces of hard cheese (40g) in recipes or snacks. For children over age 2 or older adults, this swap maintains calcium intake while reducing volume-related fullness. Pair cheese with fiber-rich foods like apples or whole-grain crackers to balance its concentrated fat content. Avoid processed cheese products, which often reintroduce water and additives, negating the digestive benefits of traditional cheesemaking.

The science is clear: water removal during cheesemaking transforms milk into a nutrient-dense, digestion-friendly food. By understanding this process, individuals can strategically incorporate cheese to optimize nutrient absorption while minimizing discomfort. Whether managing lactose sensitivity or simply seeking efficient fuel, cheese’s concentrated profile offers a practical solution rooted in both tradition and physiology.

Chihuahua Cheese vs. Queso Fresco: Unraveling the Dairy Difference

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheese is easier to digest than milk because the fermentation process breaks down lactose, a sugar found in milk that many people have difficulty digesting.

During cheese-making, bacteria convert lactose into lactic acid, reducing its content significantly. This makes cheese more tolerable for those with lactose intolerance.

Yes, cheese typically contains fewer allergens than milk because the fermentation and aging processes reduce or eliminate proteins like casein and whey that can cause sensitivities in some individuals.