Cheese wrapped in wax is a common sight, particularly with varieties like Cheddar or Gouda, but not all cheeses are treated this way. The primary reason for waxing cheese is to create a protective barrier that slows down the aging process and prevents mold growth, while also retaining moisture. This method is ideal for harder cheeses that benefit from a controlled environment to develop their flavor and texture over time. However, softer cheeses, such as Brie or Camembert, are typically wrapped in paper or foil because they require more breathability to age properly and develop their characteristic rind. Additionally, some cheeses are naturally aged in molds or brine, eliminating the need for wax. Ultimately, the choice of wrapping depends on the cheese’s type, desired texture, and aging process, ensuring each variety reaches its optimal flavor profile.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Purpose of Wax Coating | Preservation, protection from mold, moisture control, flavor development |

| Types of Cheese Typically Waxed | Hard and semi-hard cheeses (e.g., Cheddar, Gouda, Edam, Colby) |

| Types of Cheese Not Waxed | Soft cheeses (e.g., Brie, Camembert), blue cheeses, fresh cheeses (e.g., mozzarella, ricotta) |

| Wax Material | Food-grade paraffin wax, sometimes blended with other waxes (e.g., beeswax) |

| Benefits of Wax Coating | Extends shelf life, prevents drying out, inhibits mold growth, maintains shape |

| Drawbacks of Wax Coating | Can trap moisture if not applied properly, may affect texture if left on during aging |

| Alternative Coatings | Natural rinds, brine solutions, vacuum sealing, plastic wrap |

| Consumer Considerations | Wax is inedible and must be removed before consumption; some prefer waxed cheeses for longer storage |

| Environmental Impact | Wax is generally non-biodegradable but can be reused or recycled in some cases |

| Cost Implications | Waxing adds to production costs but can reduce spoilage and increase product lifespan |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Wax as a Barrier: Prevents moisture loss, mold growth, and contamination during aging and storage

- Types of Cheese for Waxing: Hard and semi-hard cheeses benefit most from wax coating

- Alternatives to Wax: Some use plastic, vacuum seals, or natural rinds instead of wax

- Waxing Process: Cheese is dipped or brushed with melted wax for an even coat

- Flavor Impact: Wax is inert, so it doesn’t affect the cheese’s taste or aroma

Wax as a Barrier: Prevents moisture loss, mold growth, and contamination during aging and storage

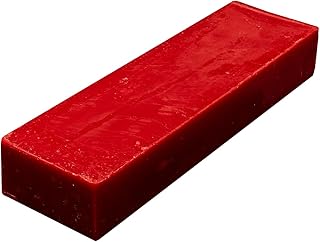

Waxing cheese isn’t just a quaint tradition—it’s a precise science aimed at preserving flavor, texture, and safety. The primary role of wax is to act as a barrier, sealing the cheese from external threats while maintaining its internal environment. For semi-hard to hard cheeses like Cheddar or Gouda, a thin, even coat of food-grade wax (typically paraffin or microcrystalline) locks in moisture, preventing the cheese from drying out during aging. This is critical because moisture loss can lead to a crumbly, unappealing texture. For optimal results, apply wax at a temperature of 140–160°F (60–70°C) to ensure it adheres smoothly without cracking.

Beyond moisture retention, wax is a formidable defense against mold and bacteria. While some molds are desirable in cheeses like Brie, uncontrolled growth can spoil the product. Wax creates an oxygen-deprived environment that stifles aerobic mold and bacterial activity, reducing the risk of contamination. However, not all cheeses benefit from this barrier—soft, surface-ripened cheeses require oxygen for their molds to flourish, making wax unsuitable. For aged cheeses, inspect the wax periodically for cracks or holes, as even small breaches can compromise its protective function.

Contamination is another silent enemy that wax effectively combats. During aging and storage, cheese is vulnerable to dust, pests, and airborne pathogens. A seamless wax coating acts as a physical shield, ensuring the cheese remains untouched by external elements. This is particularly vital for farmhouse or artisanal producers who age cheese in less controlled environments. To enhance protection, consider double-waxing or using colored wax (which often contains additional additives) for extended aging periods.

The choice to wax or not ultimately hinges on the cheese’s intended development. Wax is ideal for cheeses that age well in isolation, like Edam or Cheshire, but it stifles the transformation of bloomy-rind varieties. When applying wax, ensure the cheese is dry and at room temperature to avoid trapping moisture inside, which can lead to spoilage. For home cheesemakers, start with small batches to master the technique, and always use food-safe wax to avoid chemical leaching. In the end, wax isn’t just a wrapper—it’s a guardian, ensuring the cheese emerges from its aging journey intact and ready to delight.

What Do You Call Cheese That Isn't Yours? A Fun Worksheet

You may want to see also

Types of Cheese for Waxing: Hard and semi-hard cheeses benefit most from wax coating

Cheese wax serves a specific purpose, and not all cheeses are created equal when it comes to this protective coating. The art of waxing cheese is a precise process, and understanding which cheeses benefit from this treatment is crucial for both cheesemakers and enthusiasts. Hard and semi-hard cheeses, with their lower moisture content and denser texture, are the prime candidates for waxing, and here's why.

The Science Behind Waxing Hard Cheeses

Hard cheeses, such as Cheddar, Gouda, and Parmesan, have a lower moisture content compared to their softer counterparts. This characteristic makes them ideal for waxing. When cheese is coated in wax, it creates a barrier that prevents excessive moisture loss, which is essential for maintaining the desired texture and flavor profile. For instance, a young Cheddar, aged around 3-6 months, can be waxed to slow down the aging process, allowing it to develop a smoother, milder flavor. The wax coating also protects the cheese from mold and bacteria, ensuring a longer shelf life.

Semi-Hard Cheeses: A Delicate Balance

Semi-hard cheeses, like Gruyère, Emmental, and Havarti, occupy a unique position in the cheese spectrum. They have a slightly higher moisture content than hard cheeses but still benefit from waxing. The wax coating helps regulate moisture loss, preventing these cheeses from becoming too dry or crumbly. For example, a semi-hard cheese like Raclette, when waxed, can maintain its meltability, making it perfect for the traditional Swiss dish of the same name. The wax also provides a protective layer, allowing these cheeses to age gracefully, developing complex flavors without drying out.

Practical Considerations for Waxing

Waxing cheese is a skill that requires attention to detail. The process involves heating the wax to a specific temperature, typically around 140-150°F (60-65°C), and then carefully applying it to the cheese. It's crucial to ensure the cheese is at room temperature before waxing to avoid cracking. For larger wheels, multiple layers of wax may be applied, with each layer cooled before the next is added. This technique is particularly useful for long-term aging, as seen in traditional cheese-making regions like the Alps, where cheeses are often aged for months or even years.

Aging and Flavor Development

The primary goal of waxing hard and semi-hard cheeses is to control the aging process. By regulating moisture loss, the wax allows cheesemakers to guide the cheese's flavor development. For instance, a waxed Gouda can be aged for 6-12 months, resulting in a rich, caramelized flavor and a crystalline texture. Without the wax coating, the cheese might dry out, leading to an uneven and less desirable taste. This controlled aging process is a key reason why cheesemakers prefer waxing for these specific cheese types.

In summary, waxing is a technique tailored to the unique characteristics of hard and semi-hard cheeses. It provides a protective environment, allowing these cheeses to age gracefully, develop complex flavors, and maintain their desired texture. Whether it's a sharp, aged Cheddar or a creamy, melted Raclette, the wax coating plays a pivotal role in delivering the perfect cheese experience. This traditional method continues to be a cornerstone of cheese preservation and flavor enhancement.

Unpacking Cheese Packs: How Many Slices Are Really Inside?

You may want to see also

Alternatives to Wax: Some use plastic, vacuum seals, or natural rinds instead of wax

Cheese packaging is a delicate balance between preservation and presentation, and wax has long been a traditional method for protecting certain varieties. However, not all cheeses are suited to this treatment, leading to the exploration of alternative methods such as plastic, vacuum seals, and natural rinds. Each of these methods offers distinct advantages and is chosen based on the cheese's type, moisture content, and intended aging process.

Plastic Wrapping: A Modern Convenience

Plastic is a versatile and cost-effective alternative to wax, often used for softer, fresher cheeses like mozzarella or cream cheese. Its primary benefit lies in its ability to create an airtight seal, preventing mold growth and moisture loss. For home use, opt for food-grade plastic wraps or reusable silicone covers. When storing, ensure the cheese is wrapped tightly to avoid air pockets, and replace the wrap if it becomes loose. While plastic is practical, it’s less eco-friendly than wax, so consider biodegradable options if sustainability is a priority.

Vacuum Sealing: The Science of Preservation

Vacuum sealing is ideal for semi-hard to hard cheeses like cheddar or gouda, as it removes oxygen, the primary culprit behind spoilage. This method extends shelf life by up to 2-3 times longer than traditional wrapping. To vacuum seal cheese at home, slice it into portions, place it in a vacuum bag, and use a countertop sealer. Caution: avoid vacuum sealing soft or crumbly cheeses, as the process can alter their texture. For best results, store vacuum-sealed cheese in a cool, dark place, and consume within 4-6 weeks of sealing.

Natural Rinds: Letting Cheese Breathe

Some cheeses, like Brie or Camembert, develop their own protective rinds as they age. These natural rinds allow the cheese to breathe while shielding it from harmful bacteria. Unlike wax, which acts as a barrier, natural rinds are part of the cheese itself, contributing to flavor and texture development. If you’re aging cheese at home, maintain a humidity level of 85-90% and a temperature of 50-55°F to encourage proper rind formation. Regularly inspect the rind for unwanted mold, and trim it if necessary.

Choosing the Right Method: A Comparative Guide

The choice of packaging depends on the cheese’s characteristics and intended use. Plastic is best for short-term storage of fresh cheeses, while vacuum sealing excels for longer preservation of harder varieties. Natural rinds are ideal for cheeses meant to age, as they enhance flavor and texture. For example, a young cheddar might benefit from vacuum sealing, whereas a maturing Gruyère thrives with a natural rind. Always consider the cheese’s moisture content and desired aging process when selecting a method.

By understanding these alternatives, you can better preserve and enjoy your cheese, whether you’re a home enthusiast or a professional cheesemaker. Each method has its place, offering tailored solutions to the diverse world of cheese.

Burger King Egg and Cheese Croissan'wich Price Revealed

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Waxing Process: Cheese is dipped or brushed with melted wax for an even coat

Cheese wax, typically made from paraffin or a blend with microcrystalline wax, melts at 140–150°F (60–65°C), a temperature safe for most cheeses yet hot enough to adhere smoothly. The waxing process begins by heating the wax in a double boiler or dedicated melter to avoid overheating, which can release fumes or combust. Once melted, the cheese is either dipped fully into the wax or brushed with a silicone basting tool, ensuring an even 1/16-inch coat. This method creates a moisture-resistant barrier critical for semi-hard to hard varieties like Cheddar or Gouda, which require slow aging (3–12 months) without drying out.

The dipping technique is faster but demands precise timing: submerge the cheese for 2–3 seconds, then lift and allow the wax to set for 10–15 seconds before repeating. Brushing, while slower, offers better control for uneven surfaces or smaller batches. For optimal adhesion, the cheese surface must be dry and at room temperature (68°F/20°C). Avoid waxing soft or mold-ripened cheeses (e.g., Brie, Camembert), as the airtight seal traps excess moisture, fostering spoilage. Always use food-grade wax free of additives, and store waxed cheeses in cool (50–55°F/10–13°C), humid (85%) environments to prevent cracking.

The choice between dipping and brushing hinges on scale and texture. Artisanal producers often brush to preserve natural rinds or add decorative layers, while industrial operations favor dipping for efficiency. A second coat is essential after the first hardens, typically within 30 minutes. For aged cheeses, re-waxing every 6 months prevents gaps from forming as the wheel shrinks. Pro tip: Add 1–2% natural pigments (e.g., annatto, titanium dioxide) to the wax for color-coding or aesthetic appeal, but test compatibility first to avoid chemical reactions.

Waxing is not merely preservation—it’s a calculated trade-off. While it halts mold growth and slows oxygen exchange, it also traps volatile compounds, muting flavor development compared to breathable coatings like cloth or paper. However, for long-aging cheeses, this sacrifice is justified. To remove wax, peel it off with a non-serrated knife, then repurpose it by melting and filtering through cheesecloth for future batches. Properly applied, a wax coat extends shelf life by 2–3 years, making it indispensable for hard varieties destined for cellars or retail shelves.

For home cheesemakers, mastering the waxing process requires practice. Start with small wheels (1–2 lbs) and use a kitchen thermometer to monitor wax temperature. If bubbles form during dipping, pierce them with a skewer to ensure full coverage. Cracks post-waxing indicate either too-cold cheese or too-hot wax; remedy by warming the cheese slightly or reducing wax temperature. While labor-intensive, the method rewards with a stable, mature product—proof that sometimes, the oldest techniques remain the most effective.

Finding the White Door in Cheese Escape: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Flavor Impact: Wax is inert, so it doesn’t affect the cheese’s taste or aroma

Wax-coated cheeses often spark curiosity, but their flavor remains unaltered by this protective layer. Unlike materials like wood or leaves, which can impart distinct aromas and tastes, wax is chemically inert. This means it doesn’t interact with the cheese’s surface, ensuring the flavor profile develops solely from the cheese itself, its aging process, and any added cultures or ingredients. For example, a wax-wrapped Gouda retains its nutty, caramelized notes without any waxy undertones, proving the coating’s neutrality.

Consider the aging process: wax acts as a barrier, not a flavor contributor. Cheeses like Edam or Cheddar, often waxed for preservation, rely on this inert quality to maintain their intended taste. If wax influenced flavor, cheesemakers would need to account for its impact, potentially altering recipes or aging times. Instead, wax serves purely as a shield, allowing the cheese to mature undisturbed. This makes it ideal for varieties where consistency is key, such as mass-produced blocks or long-aging cheeses.

Practical tip: when selecting wax-coated cheese, focus on the type and age rather than the wax itself. For instance, a 12-month aged waxed Gouda will have a sharper flavor than its 6-month counterpart, but the wax won’t skew this difference. Remove the wax before serving, as it’s inedible, and let the cheese breathe for 15–30 minutes to enhance its natural aroma and texture. This ensures you experience the cheese as intended, without any external interference.

Comparatively, cheeses wrapped in natural materials like bark or cloth absorb external flavors, which can be desirable for certain varieties. Wax, however, is chosen specifically for its lack of impact. This makes it a reliable choice for cheesemakers aiming to preserve the purity of their product. For home storage, keep waxed cheeses in a cool, dry place, as the wax prevents moisture loss and mold growth without altering the internal chemistry that drives flavor development.

In essence, wax is the unsung hero of cheese preservation—invisible in taste but invaluable in function. Its inert nature ensures the cheese’s flavor remains untainted, making it a go-to for both artisanal and commercial producers. Next time you unwrap a wax-coated cheese, appreciate the science behind its unassuming exterior: it’s there to protect, not to flavor.

Caring for Your Wooden Cheese Board: Tips for Longevity and Beauty

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheese is wrapped in wax to create a protective barrier that prevents mold growth, moisture loss, and contamination while allowing the cheese to age properly.

Harder cheeses like Cheddar, Gouda, and Edam are commonly wrapped in wax because they benefit from the controlled aging environment it provides.

Not all cheeses need wax wrapping. Soft cheeses, like Brie or Camembert, require breathable packaging to develop their characteristic rind and texture, while others, like fresh cheeses, are consumed quickly and don’t need aging.

No, the wax itself is flavorless and does not affect the taste of the cheese. It is purely a protective layer and is removed before eating.

No, the wax is not edible and should always be removed before consuming the cheese. It is intended for protection, not consumption.