Cheese and milk can sometimes cause stomach discomfort due to their lactose and fat content. Lactose, a sugar found in dairy products, requires the enzyme lactase to be properly digested. Many people have lactose intolerance, meaning their bodies produce insufficient lactase, leading to symptoms like bloating, gas, and stomach pain when consuming dairy. Additionally, the high fat content in cheese can slow digestion, potentially causing feelings of fullness or discomfort. Understanding these factors can help explain why cheese and milk might block or irritate your stomach, and exploring alternatives or digestive aids may provide relief.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Lactose Intolerance | Inability to digest lactose, a sugar in milk and dairy, due to insufficient lactase enzyme. Can cause bloating, gas, and stomach discomfort. |

| Casein Sensitivity | Reaction to casein, a protein in milk and cheese, leading to digestive issues like bloating and constipation. |

| High Fat Content | Cheese and whole milk are high in fat, which slows digestion and can cause feelings of fullness or blockage. |

| Dairy Allergy | Immune response to dairy proteins, causing symptoms like stomach pain, nausea, and vomiting. |

| Lactose Malabsorption | Partial inability to digest lactose, leading to similar symptoms as lactose intolerance but less severe. |

| Gut Microbiome Imbalance | Dairy can disrupt gut bacteria, causing fermentation and gas production, leading to bloating and discomfort. |

| Slow Gastric Emptying | High-fat dairy products can delay stomach emptying, causing a sensation of blockage. |

| Individual Sensitivity | Some individuals may have unique sensitivities to dairy components not related to lactose or casein. |

| Processed Dairy | Additives or processing methods in certain dairy products can exacerbate digestive issues. |

| Overeating Dairy | Consuming large amounts of cheese or milk can overwhelm the digestive system, leading to discomfort. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Lactose Intolerance: Inability to digest lactose, a sugar in dairy, causes bloating, gas, and stomach discomfort

- High Fat Content: Dairy fats slow digestion, leading to feelings of fullness and potential stomach blockage

- Casein Sensitivity: Reaction to milk protein casein can cause inflammation and digestive issues in some individuals

- Dairy and Constipation: Calcium in dairy can bind stool, slowing transit and causing stomach blockage or discomfort

- Fermentation in Gut: Undigested lactose ferments in the gut, producing gas and bloating, mimicking a blocked stomach

Lactose Intolerance: Inability to digest lactose, a sugar in dairy, causes bloating, gas, and stomach discomfort

Ever wondered why a creamy latte or a slice of cheddar leaves you doubled over in discomfort? The culprit might be lactose intolerance, a condition where your body lacks the enzyme lactase, essential for breaking down lactose, the sugar found in dairy products. Without lactase, lactose ferments in the gut, producing gas and triggering bloating, cramps, and diarrhea. This isn't a rare phenomenon; it affects millions worldwide, with prevalence varying across ethnicities. For instance, up to 90% of East Asians and 80% of African Americans experience lactose intolerance, compared to about 5% of Northern Europeans.

Understanding lactose intolerance begins with recognizing its symptoms. Typically, within 30 minutes to 2 hours of consuming dairy, you might experience abdominal pain, bloating, gas, nausea, or even vomiting. The severity depends on how much lactose you’ve consumed and how much lactase your body produces. For example, hard cheeses like cheddar contain less lactose than milk, so they’re often better tolerated. Similarly, yogurt with live cultures can be easier to digest because the bacteria partially break down lactose. If you suspect lactose intolerance, a simple elimination diet or a hydrogen breath test can confirm the diagnosis.

Managing lactose intolerance doesn’t mean swearing off dairy entirely. Start by gradually reducing your intake to identify your tolerance threshold. Many people can handle small amounts of lactose without symptoms. Opt for lactose-free milk, which is treated with lactase to break down the sugar, or try plant-based alternatives like almond, soy, or oat milk. When cooking, substitute milk with lactose-free options or use lactase enzymes in tablet or drop form to pre-treat dairy products. For instance, adding a few drops of lactase to milk 24 hours before consumption can make it more digestible.

For those who love cheese, focus on aged varieties like Parmesan or Swiss, which naturally contain minimal lactose. Pairing dairy with other foods can also slow digestion, reducing the likelihood of symptoms. If you’re dining out, ask about ingredients and opt for dishes less likely to contain hidden dairy, like salads with oil-based dressings or grilled meats. Remember, lactose intolerance isn’t a deficiency or an allergy—it’s a common digestive issue with manageable solutions. By making informed choices, you can still enjoy dairy without the discomfort.

Prevent Runny Beer Cheese: Simple Tips for Perfect Consistency Every Time

You may want to see also

High Fat Content: Dairy fats slow digestion, leading to feelings of fullness and potential stomach blockage

Dairy products like cheese and milk are notorious for their high fat content, which can significantly impact digestion. Fats, by nature, take longer to break down compared to carbohydrates or proteins. When you consume dairy, the fats form a thick chyme in the stomach, slowing the overall digestive process. This delayed transit time often results in a prolonged feeling of fullness, which, while not inherently harmful, can mimic the sensation of a blocked stomach, especially if consumed in large quantities. For instance, a single ounce of cheddar cheese contains about 9 grams of fat, and a cup of whole milk has around 8 grams—both contributing to this effect.

To mitigate this, consider moderating portion sizes. A practical tip is to limit high-fat dairy intake to 20–30 grams of fat per meal, particularly for individuals over 50 or those with pre-existing digestive issues. Pairing dairy with fiber-rich foods like whole grains or vegetables can also aid digestion by balancing the fat content. For example, having a slice of cheese with an apple or a glass of milk with oatmeal can help prevent the overwhelming sensation of fullness.

From a comparative standpoint, low-fat or skim dairy options offer a viable alternative. A cup of skim milk contains less than 0.5 grams of fat, significantly reducing the likelihood of digestive slowdown. However, it’s essential to note that fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) in dairy are better absorbed in the presence of fat, so completely eliminating fat isn’t always ideal. Striking a balance—such as opting for 1% milk or part-skim mozzarella—can provide both nutritional benefits and easier digestion.

Finally, understanding individual tolerance is key. Some people naturally produce less lactase, the enzyme needed to digest lactose, which can exacerbate feelings of blockage when combined with high fat content. If you suspect lactose intolerance, try lactose-free dairy products or take lactase supplements before consumption. Monitoring symptoms after specific dairy intake can help identify personal thresholds, ensuring you enjoy dairy without discomfort.

Cheese Calculation Guide: Serving 100 Guests with Perfect Portions

You may want to see also

Casein Sensitivity: Reaction to milk protein casein can cause inflammation and digestive issues in some individuals

Ever wondered why a creamy latte or a slice of cheddar leaves you with a bloated, uncomfortable stomach? The culprit might be casein, a protein found in dairy products like milk and cheese. For some individuals, casein sensitivity triggers an immune response, leading to inflammation and digestive issues. Unlike lactose intolerance, which involves the sugar in milk, casein sensitivity targets the protein itself, making it a distinct and often overlooked condition.

Imagine your digestive system as a bouncer at an exclusive club. For most people, casein is a VIP guest, smoothly passing through without issue. But for those with casein sensitivity, it’s like casein is on the blacklist—the bouncer (your immune system) recognizes it as a threat and sounds the alarm. This immune response can cause symptoms like bloating, gas, abdominal pain, and even diarrhea. Over time, chronic inflammation from repeated exposure may contribute to more serious conditions like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or leaky gut syndrome.

If you suspect casein sensitivity, start by keeping a food diary to track symptoms after consuming dairy. Gradually eliminate milk, cheese, and other dairy products for 2–3 weeks to see if symptoms improve. Reintroduce them one at a time to pinpoint the trigger. For those diagnosed with casein sensitivity, alternatives like almond milk, coconut yogurt, or nutritional yeast (for that cheesy flavor) can help maintain a balanced diet. Probiotics and digestive enzymes may also aid in managing symptoms, but consult a healthcare provider before starting any supplements.

Here’s a practical tip: when dining out, ask about hidden dairy sources like butter in sauces or casein in processed foods. Reading labels is crucial, as casein can lurk in unexpected places, such as baked goods or protein powders. For children, who are more commonly affected, consider calcium-fortified plant-based milks to ensure they meet their nutritional needs. Remember, casein sensitivity isn’t a life sentence—with awareness and adjustments, you can enjoy a symptom-free digestive experience.

Crafting the Perfect Whole Foods Cheese Board: Tips and Tricks

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$8.69 $10.22

Dairy and Constipation: Calcium in dairy can bind stool, slowing transit and causing stomach blockage or discomfort

Calcium, a key nutrient in dairy products like cheese and milk, plays a dual role in digestive health. While it’s essential for bone strength and muscle function, its interaction with the digestive system can lead to constipation. When consumed in excess, calcium binds with oxalates and other compounds in the gut, forming insoluble compounds that harden stool. This process slows intestinal transit, causing discomfort and potential blockage. For individuals prone to constipation, even moderate dairy intake—such as two servings of cheese or a glass of milk daily—can exacerbate symptoms.

Consider the mechanism: calcium acts as a natural firming agent in the gut. In dairy, it combines with fats and proteins, creating a denser, slower-moving mass. This effect is particularly noticeable in aged cheeses, which contain higher calcium concentrations due to the fermentation process. For example, a 30g serving of cheddar cheese provides approximately 200mg of calcium, enough to contribute to stool hardening in sensitive individuals. Pairing dairy with low-fiber meals further compounds the issue, as fiber is crucial for softening stool and promoting regular bowel movements.

To mitigate dairy-induced constipation, start by tracking your intake. Adults should aim for the recommended daily calcium intake of 1,000–1,200mg, but distribute it evenly throughout the day to avoid overloading the digestive system. If constipation persists, reduce portion sizes or opt for lower-calcium dairy alternatives like yogurt, which contains probiotics that support gut health. Incorporating fiber-rich foods—such as leafy greens, whole grains, or prunes—can counteract calcium’s binding effect. For instance, pairing a small serving of cheese with a fiber-rich salad can help maintain stool consistency.

For those with lactose intolerance, the issue may extend beyond calcium. Undigested lactose can ferment in the gut, producing gas and bloating, which mimics constipation symptoms. In such cases, lactose-free dairy or plant-based alternatives like almond or soy milk may alleviate discomfort. However, these alternatives often contain added calcium, so monitor labels to avoid excessive intake. Hydration is equally critical; aim for 8–10 cups of water daily to soften stool and facilitate smoother transit, regardless of dairy consumption.

Finally, individual tolerance varies, so experimentation is key. If dairy consistently causes blockage, consider a temporary elimination diet to assess its impact. Gradually reintroduce small servings while monitoring symptoms. Consulting a dietitian can provide personalized guidance, especially for those with underlying conditions like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). By balancing calcium intake, fiber, and hydration, you can enjoy dairy without compromising digestive comfort.

Easy Stove-Top Method to Melt Velveeta Cheese Perfectly Every Time

You may want to see also

Fermentation in Gut: Undigested lactose ferments in the gut, producing gas and bloating, mimicking a blocked stomach

Lactose, a sugar found in milk and dairy products, requires the enzyme lactase for digestion. When lactase production decreases—a condition known as lactase deficiency—undigested lactose moves into the large intestine. Here, gut bacteria ferment the lactose, producing gases like hydrogen, methane, and carbon dioxide. This fermentation process leads to bloating, abdominal discomfort, and a sensation often described as a "blocked stomach." For individuals with lactose intolerance, even small amounts of dairy can trigger these symptoms, making it essential to understand the role of fermentation in gut distress.

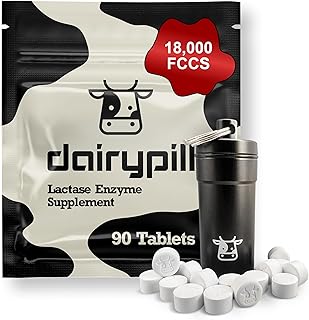

To mitigate the effects of lactose fermentation, consider reducing dairy intake or opting for lactose-free alternatives. Over-the-counter lactase enzymes, such as Lactaid, can also aid digestion when consumed before dairy products. For example, taking 3,000–9,000 FCC units of lactase enzyme with a meal can help break down lactose, reducing gas and bloating. Additionally, fermented dairy products like yogurt and kefir contain live cultures that assist in lactose digestion, making them easier to tolerate for some individuals. Monitoring portion sizes and pairing dairy with other foods can further minimize discomfort.

Comparing lactose intolerance to other digestive issues highlights the specificity of this condition. Unlike irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or gluten sensitivity, lactose intolerance is directly linked to enzyme deficiency and bacterial fermentation. While IBS involves a broader range of triggers and symptoms, lactose intolerance is predictable and manageable through dietary adjustments. Recognizing this distinction allows for targeted solutions, such as avoiding lactose or using enzyme supplements, rather than adopting a one-size-fits-all approach to gut health.

For those experiencing persistent symptoms, keeping a food diary can help identify lactose thresholds and trigger foods. Start by eliminating dairy for two weeks, then reintroduce small amounts gradually to assess tolerance. Practical tips include choosing hard cheeses like cheddar, which are naturally lower in lactose, or incorporating dairy at the end of a meal to slow digestion. Understanding the fermentation process empowers individuals to make informed choices, transforming a "blocked stomach" from a mystery into a manageable condition.

Taco Bell Cheese Quesadilla: Unveiling Its Carbohydrate Content

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheese and milk contain lactose, a sugar that some people have difficulty digesting due to lactose intolerance. Undigested lactose can ferment in the gut, causing bloating, gas, and a feeling of blockage.

Yes, for some individuals, dairy products like cheese and milk can lead to constipation. This may be due to lactose intolerance, low fiber content, or the way dairy affects gut motility in certain people.

Cheese is high in fat, which slows down digestion, making it feel like it’s "stuck" in your stomach. Additionally, lactose intolerance or dairy sensitivity can cause discomfort and a heavy feeling.

If milk makes your stomach feel blocked, it could be due to lactose intolerance or a dairy sensitivity. The undigested lactose can cause gas, bloating, and a sensation of fullness or blockage.