The question of whether Asian cultures historically had cheese is a fascinating exploration of culinary history and cultural exchange. While cheese is often associated with European traditions, evidence suggests that various forms of cheese have been produced and consumed across Asia for centuries. From the fermented milk products of Central Asia, such as *qurut* and *chortan*, to the soy-based cheeses of East Asia like *tofu* and *yuba*, and even the buffalo milk cheeses of India, such as *paneer* and *chhena*, Asian cultures have developed unique dairy and non-dairy cheese-like products. These innovations reflect the region's diverse agricultural practices, dietary needs, and creative adaptations of ingredients, challenging the notion that cheese is exclusively a Western invention.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Historical Evidence | Limited; traditional Asian cultures had minimal dairy consumption due to lactose intolerance prevalence. |

| Traditional Dairy Products | Focused on fermented milk products like kumis (Central Asia), chhurpi (Himalayan regions), and suanrinyao (China), rather than aged cheese. |

| Cheese Production | Historically rare, with exceptions in regions influenced by nomadic cultures (e.g., Mongolia, parts of India). |

| Modern Adoption | Increased cheese consumption and production in Asia due to globalization, urbanization, and Western influence. |

| Regional Variations | Some regions (e.g., India, Nepal) have ancient forms of cheese-like products (e.g., paneer, chhurpi), while others (e.g., East Asia) have minimal traditional cheese culture. |

| Cultural Significance | Cheese was not a staple in most Asian cuisines historically, unlike in European cultures. |

| Current Trends | Rising demand for cheese in Asia, with local production and adaptation to regional tastes (e.g., flavored cheeses in Japan, mozzarella in China). |

| Lactose Intolerance | High prevalence in many Asian populations historically limited dairy and cheese consumption. |

| Influence of Trade | Historical trade routes (e.g., Silk Road) introduced some dairy practices, but cheese remained uncommon. |

| Modern Innovations | Development of lactose-free or low-lactose cheese products to cater to Asian markets. |

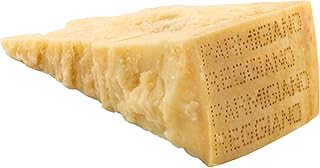

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Early Cheese Evidence in Asia: Archaeological findings suggest cheese-making in ancient Mongolia and Central Asia

- Traditional Asian Dairy Products: Foods like *ruzhou fu* (China) and *chhurpi* (Himalayas) resemble cheese

- Role of Nomadic Cultures: Nomadic tribes in Asia likely developed cheese for preserving milk

- Influence of Trade Routes: Silk Road may have spread cheese-making techniques across Asia

- Modern Asian Cheese Adoption: Western cheese varieties now popular in Asian cuisines and markets

Early Cheese Evidence in Asia: Archaeological findings suggest cheese-making in ancient Mongolia and Central Asia

Archaeological discoveries in Mongolia and Central Asia challenge the notion that cheese-making was solely a European or Middle Eastern innovation. Recent findings reveal that ancient herding communities in these regions were producing cheese as early as 1300 BCE. Researchers identified strainers made from sheep stomachs, likely used to separate curds from whey, in burial sites along the border of modern-day Mongolia and Russia. These artifacts, preserved by the region’s arid climate, provide tangible evidence of early dairy processing techniques. Chemical analysis of residues on these strainers confirmed the presence of milk fats, further supporting the case for ancient cheese production.

To understand the significance of these findings, consider the environmental and cultural context of ancient Mongolia and Central Asia. These regions were home to nomadic herders who relied heavily on livestock for sustenance. Milk from sheep, goats, and yaks was a staple, but its perishable nature necessitated preservation methods. Cheese-making offered a practical solution, transforming milk into a more durable and portable food source. This innovation likely played a crucial role in sustaining nomadic lifestyles, enabling herders to carry nutrient-dense provisions across vast distances. The discovery of cheese-making tools in burial sites also suggests that dairy processing held cultural or ritual importance, possibly symbolizing wealth or status.

While the evidence is compelling, interpreting these archaeological findings requires caution. The strainers and residues alone do not reveal the exact type of cheese produced or the methods used. Early cheeses in this region were likely simple, unaged varieties, similar to soft curds or fresh cheeses. Recreating these ancient recipes today would involve using traditional techniques, such as coagulating milk with natural enzymes or acids, and straining it through organic materials like animal stomachs. Modern enthusiasts interested in experimenting with historical cheese-making can draw inspiration from these practices, though adapting them to contemporary tools and ingredients.

The takeaway from these discoveries is twofold. First, they expand our understanding of global culinary history, demonstrating that cheese-making was not confined to a single cultural or geographic origin. Second, they highlight the ingenuity of ancient communities in addressing practical challenges through food technology. For those curious about early Asian dairy traditions, exploring these findings offers a fascinating glimpse into the intersection of survival, culture, and cuisine. By studying such evidence, we not only honor the resourcefulness of our ancestors but also gain insights into sustainable food practices that remain relevant today.

Refrigerate or Not? Cheese Baked Bread Storage Tips Revealed

You may want to see also

Traditional Asian Dairy Products: Foods like *ruzhou fu* (China) and *chhurpi* (Himalayas) resemble cheese

While European cheeses dominate global consciousness, Asia boasts its own dairy traditions, often overlooked in the "cheese" conversation. Products like *ruzhou fu* from China and *chhurpi* from the Himalayas challenge our Eurocentric definition of cheese, offering unique textures, flavors, and cultural significance.

Ruzhou fu, a Chinese specialty, is a fermented milk product with a crumbly texture and a tangy, slightly sour taste. Made from cow's or goat's milk, it's often enjoyed as a snack or used to add a savory depth to dishes. Its production involves a simple process of curdling milk with vinegar or lemon juice, followed by pressing and drying. This method, while different from traditional European cheesemaking, results in a product that shares the characteristic fermented flavor profile associated with cheese.

Similarly, *chhurpi*, a staple in the Himalayan regions, is a hard, chewy cheese made from yak or cow's milk. Its production involves a lengthy process of curdling, pressing, and aging, often resulting in a product that can be stored for months. *Chhurpi* is not just a food source but holds cultural importance, often used in rituals and traded as a valuable commodity. Its dense texture and strong flavor make it a unique culinary experience, far removed from the soft, creamy cheeses often associated with Western palates.

These examples highlight the diversity of dairy products across Asia, challenging the notion that cheese is solely a European invention. They demonstrate the ingenuity of different cultures in utilizing milk, adapting techniques to local resources and preferences. While *ruzhou fu* and *chhurpi* may not fit the traditional Western definition of cheese, they are undoubtedly fermented dairy products with distinct characteristics and cultural significance, deserving recognition in the global dairy landscape.

Babybel Mini Light Cheese: Uncovering Its Fat Content and Nutritional Value

You may want to see also

Role of Nomadic Cultures: Nomadic tribes in Asia likely developed cheese for preserving milk

The vast steppes and deserts of Asia, where nomadic tribes roamed with their herds, presented a unique challenge: how to preserve the bounty of milk from their animals in a land devoid of refrigeration. This necessity likely sparked innovation, leading to the development of cheese as a practical solution. Unlike settled civilizations with access to pottery and storage facilities, nomads needed a portable, long-lasting food source. Cheese, with its concentrated nutrients and extended shelf life, fit the bill perfectly.

Imagine a yurt on the Mongolian plains, where a herder carefully curdles mare's milk, separating the solids from the whey. This simple process, repeated across the continent, became a cornerstone of nomadic survival.

The evidence lies not only in historical accounts but also in the very DNA of traditional Asian cheeses. Take, for instance, the Mongolian "byaslag," a dried curd cheese made from cow, sheep, or goat milk. Its hard, crumbly texture and long shelf life are testaments to the ingenuity of nomadic cheese-making techniques. Similarly, the Kyrgyz "kurut" and the Tibetan "chhurpi" showcase the diversity of cheese forms developed by different nomadic groups, each adapted to their specific environment and available resources. These cheeses were not just food; they were currency, trade goods, and symbols of hospitality, woven into the very fabric of nomadic culture.

The process itself was often a communal affair, with women playing a central role in milk processing and cheese production. This knowledge, passed down through generations, ensured the survival of these traditions even in the face of changing lifestyles and modernization.

While the origins of cheese in Asia are still debated, the role of nomadic cultures in its development is undeniable. Their need for portable, nutrient-dense food in harsh environments drove innovation, leading to the creation of unique cheese varieties that continue to be enjoyed today. From the high altitudes of the Himalayas to the vast grasslands of Central Asia, the legacy of nomadic cheese-making is a testament to human ingenuity and the enduring bond between people and their livestock. Understanding this history not only enriches our culinary knowledge but also highlights the profound impact of cultural practices on food traditions.

Wendy's Nacho Cheese Burger: Ingredients, Toppings, and Flavor Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$12.29 $18.99

Influence of Trade Routes: Silk Road may have spread cheese-making techniques across Asia

The Silk Road, a network of ancient trade routes connecting the East and West, was more than a conduit for silk, spices, and precious metals—it was a highway for cultural exchange, including culinary techniques. Among the many goods and ideas that traveled along these routes, cheese-making methods may have been a significant, yet underappreciated, transfer. Historical records and archaeological findings suggest that cheese production, originating in the Fertile Crescent, could have spread eastward through merchants, travelers, and nomadic tribes who frequented these paths. This diffusion challenges the notion that cheese was solely a European or Middle Eastern invention, highlighting its potential role in Asian culinary history.

Consider the practicalities of cheese-making in a pre-refrigeration world. Traders needed a way to preserve milk, and cheese provided a durable, nutrient-dense solution. Along the Silk Road, nomadic herders like the Mongols and Kyrgyz were adept at animal husbandry, raising goats, sheep, and yaks. These groups likely adopted cheese-making techniques from their interactions with Persian and Central Asian cultures, adapting them to local conditions. For instance, the Kyrgyz *kumis* (fermented mare’s milk) and Mongolian *airag* share similarities with early cheese-making processes, suggesting a shared knowledge base. Such adaptations demonstrate how trade routes facilitated not just the movement of goods, but the evolution of techniques to suit regional resources.

To trace this influence, examine the geographical spread of cheese varieties in Asia. In Central Asia, *kurut*—hard, dried cheese balls—resemble techniques that could have been introduced via the Silk Road. Moving eastward, Chinese texts from the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) mention *lactos*, a dairy product possibly akin to cheese, though its exact nature remains debated. Further south, India’s *paneer* and Tibet’s *chura kampo* (dried cheese) showcase diverse interpretations of cheese-making, potentially influenced by cross-cultural exchanges. These examples illustrate how the Silk Road may have acted as a catalyst, enabling the spread of cheese-making across vast distances and diverse cultures.

However, caution is warranted when attributing all Asian cheese traditions to the Silk Road. Local innovations and independent developments cannot be overlooked. For instance, the use of rennet substitutes like fig juice or vinegar in some Asian cheese recipes diverges from Central Asian methods, suggesting indigenous experimentation. Still, the Silk Road’s role as a facilitator of knowledge exchange remains compelling. By examining trade records, archaeological dairy artifacts, and linguistic parallels in cheese terminology, researchers can piece together a more nuanced understanding of this culinary diffusion.

In practical terms, modern enthusiasts can draw inspiration from this historical exchange. Recreating Silk Road-era cheese recipes using local ingredients—such as yak milk in the Himalayas or buffalo milk in Southeast Asia—offers a tangible way to connect with this legacy. Start by experimenting with simple curdling techniques, like heating milk with lemon juice or vinegar, and gradually incorporate traditional spices like cumin or coriander for authenticity. Such hands-on exploration not only honors the past but also highlights the enduring impact of trade routes on global cuisine.

Why Cheese and Milk Cause Stomach Blockages: Understanding Lactose Intolerance

You may want to see also

Modern Asian Cheese Adoption: Western cheese varieties now popular in Asian cuisines and markets

Asian cuisines, traditionally light on dairy, are now embracing Western cheese varieties with surprising enthusiasm. From creamy mozzarella topping Korean kimchi pizzas to sharp cheddar melting into Japanese curry rice, the fusion is undeniable. This isn’t just a trend; it’s a cultural shift driven by globalization, urban migration, and a younger generation eager to experiment. Supermarkets across Asia now dedicate entire aisles to imported cheeses, and local producers are crafting hybrids like miso-infused camembert. The result? A culinary landscape where East meets West on a plate, often with delicious consequences.

Consider the practicalities of this adoption. For instance, in Taiwan, mozzarella has become a staple in night market snacks like fried cheese sticks, while in India, paneer is increasingly paired with Western cheeses like gouda in modern fusion dishes. Chefs are experimenting with cheese as a texture enhancer, not just a flavor additive—think crispy cheese crusts on Thai curries or grated parmesan sprinkled over Vietnamese banh xeo. For home cooks, the key is balancing fat content: softer cheeses like brie work well in lighter dishes, while harder cheeses like pecorino add depth without overwhelming traditional flavors. Start small, taste often, and don’t be afraid to mix cultures in your kitchen.

The market data backs this up. In Japan, cheese imports surged by 30% over the past decade, with cheddar and mozzarella leading the charge. China’s cheese consumption, though still modest, grew by 15% annually, fueled by urban millennials. Even in Southeast Asia, where lactose intolerance is common, low-lactose cheeses like halloumi are gaining traction. This isn’t mere imitation; it’s adaptation. Asian chefs are reimagining Western cheeses to suit local palates, like adding yuzu to cream cheese for a tangy twist or blending blue cheese with soy sauce for umami depth. The takeaway? Cheese is no longer a foreign ingredient—it’s becoming a versatile tool in the Asian culinary toolkit.

However, challenges remain. Traditionalists argue that cheese disrupts the delicate balance of Asian flavors, and health concerns linger, especially in regions unaccustomed to high dairy intake. For those experimenting, moderation is key. Pair strong cheeses with robust flavors like gochujang or miso to avoid clashing, and opt for smaller portions to let the cheese complement, not dominate. For lactose-sensitive individuals, aged cheeses like cheddar or gruyère are better tolerated due to lower lactose content. The goal isn’t to Westernize Asian cuisine but to enrich it—to create dishes that honor tradition while embracing innovation.

In the end, the rise of Western cheese in Asia is a testament to the dynamism of food culture. It’s not about replacing tofu with cheddar but about expanding possibilities. Next time you’re in a Tokyo izakaya or a Bangkok food court, look for the cheese—it’s there, quietly revolutionizing the menu. Whether you’re a chef, a home cook, or a curious eater, this fusion offers a world of flavor waiting to be explored. Just remember: the best dishes are the ones that tell a story, and this one is about bridges, not boundaries.

Newberry Indiana Cheese Factory Closure: What Happened and Why?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, Asian cultures have a long history of cheese production, though it varies widely by region and type.

Examples include Chinese *rubing*, Indian *paneer*, Mongolian *byaslag*, and Tibetan *chura loenpa*.

Cheese is not as prevalent in Asian cuisine as in Western cultures, but it is used in specific dishes and regions.

Asian cheeses are often fresher, softer, and less aged, with milder flavors, and are typically used in cooking rather than eaten alone.

Yes, modern Asian cuisine often incorporates Western-style cheeses in fusion dishes, such as cheese-filled dumplings or cheese-topped ramen.