Cheese is a beloved food enjoyed worldwide, but its origins often spark curiosity. At its core, cheese is indeed a product derived from milk, typically from cows, goats, sheep, or buffalo. The process begins with the coagulation of milk, often using enzymes like rennet or bacterial cultures, which separates the milk into curds (solid parts) and whey (liquid). These curds are then pressed, aged, and sometimes treated with additional ingredients to create the diverse array of cheeses we know today. Understanding that cheese fundamentally comes from milk highlights the intricate relationship between dairy farming and culinary craftsmanship.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Origin of Cheese | Cheese is primarily made from milk, which is the main ingredient. |

| Milk Source | Most cheese is produced from cow's milk, but it can also be made from the milk of goats, sheep, buffalo, and other mammals. |

| Production Process | Cheese is made by curdling milk using rennet or acidic substances, then draining, pressing, and aging the curds. |

| Types of Cheese | There are hundreds of varieties, each with unique flavors, textures, and production methods, all originating from milk. |

| Nutritional Content | Cheese retains many nutrients from milk, including protein, calcium, vitamins, and minerals, though it is generally higher in fat and calories. |

| Lactose Content | Most cheese has low lactose levels due to the fermentation process, making it tolerable for some lactose-intolerant individuals. |

| Alternatives | Non-dairy "cheeses" made from plant-based milks (e.g., almond, soy, or cashew) exist but are not traditional cheese. |

| Historical Use | Cheese production dates back thousands of years as a method to preserve milk. |

| Global Consumption | Cheese is a staple in many cultures worldwide, with diverse regional variations, all rooted in milk-based production. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Types of Milk Used: Cow, goat, sheep, buffalo milk are commonly used for cheese production

- Cheesemaking Process: Coagulation, curdling, pressing, and aging transform milk into cheese

- Milk-to-Cheese Ratio: Approximately 10 pounds of milk yields 1 pound of cheese

- Non-Dairy Alternatives: Plant-based cheeses use nuts, soy, or coconut milk instead of dairy

- Nutritional Differences: Cheese retains milk's protein and calcium but has higher fat and calories

Types of Milk Used: Cow, goat, sheep, buffalo milk are commonly used for cheese production

Cheese production is an art that begins with milk, but not all milks are created equal. The type of milk used significantly influences the flavor, texture, and nutritional profile of the final product. Among the most commonly used milks are cow, goat, sheep, and buffalo milk, each bringing its unique characteristics to the cheeseboard. Understanding these differences can help both cheesemakers and enthusiasts appreciate the diversity of cheeses available.

Cow’s milk is the most widely used in cheese production, accounting for over 90% of global cheese varieties. Its mild, creamy flavor and balanced fat content make it versatile for everything from sharp cheddars to soft bries. For home cheesemakers, cow’s milk is an excellent starting point due to its availability and consistency. When selecting cow’s milk for cheese, opt for raw or pasteurized (not ultra-pasteurized) milk to ensure proper curdling. A practical tip: use 1 gallon of milk to yield approximately 1–1.5 pounds of cheese, depending on the type.

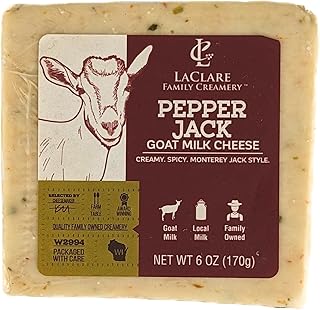

Goat’s milk, while less common, offers a distinct tangy and slightly sweet flavor that shines in cheeses like chèvre and feta. Its lower lactose and fat content make it easier to digest for some individuals. However, goat’s milk can be more challenging to work with due to its smaller fat globules, which affect curd formation. For best results, use fresh goat’s milk and maintain precise temperature control during the cheesemaking process. A 1-gallon batch typically yields around 1 pound of cheese, making it ideal for small-scale production.

Sheep’s milk is a powerhouse in the cheese world, prized for its rich, nutty flavor and high fat and protein content. Cheeses like pecorino and manchego showcase its intensity and complexity. While sheep’s milk is less accessible and more expensive than cow’s or goat’s milk, its yield is higher—1 gallon can produce up to 2 pounds of cheese. This makes it a valuable choice for artisanal cheesemakers looking to create premium products. However, its strong flavor may not appeal to all palates, so consider blending it with other milks for a milder result.

Buffalo milk, though less common globally, is the star of iconic cheeses like mozzarella di bufala. Its high butterfat content (typically 7–8%) gives cheeses a luxuriously creamy texture and rich flavor. Buffalo milk is more delicate than cow’s milk and requires careful handling to avoid curd breakdown. Due to its cost and limited availability, it’s often reserved for specialty cheeses. A key takeaway: while buffalo milk yields less cheese per gallon (about 1 pound), its unparalleled texture and taste make it worth the investment for connoisseurs.

In summary, the choice of milk is a defining factor in cheese production, shaping everything from flavor to yield. Cow’s milk offers versatility, goat’s milk brings tanginess, sheep’s milk delivers richness, and buffalo milk provides unmatched creaminess. By experimenting with these milks, cheesemakers can craft a wide array of cheeses tailored to diverse tastes and preferences. Whether you’re a novice or a seasoned artisan, understanding these milks will elevate your cheesemaking journey.

Artisan Cheese Aging: Unveiling the Time-Honored Craft of Flavor Development

You may want to see also

Cheesemaking Process: Coagulation, curdling, pressing, and aging transform milk into cheese

Cheese begins with milk, but the transformation from liquid to solid is a delicate dance of science and art. The cheesemaking process hinges on four critical steps: coagulation, curdling, pressing, and aging. Each phase alters the milk’s structure, texture, and flavor, culminating in the diverse cheeses we know and love. Understanding these steps reveals the precision required to turn a simple ingredient into a culinary masterpiece.

Coagulation is the first step, where milk transitions from liquid to a gel-like state. This is achieved by adding a coagulant, typically rennet or microbial enzymes, which break down the milk protein casein. For example, animal rennet works within 30–60 minutes at temperatures between 86–104°F (30–40°C), while microbial alternatives may take longer. The goal is to form a weak curd that holds its shape but remains soft. Over-coagulation can lead to a tough, rubbery texture, so timing and temperature control are crucial.

Once coagulated, the curd is cut into smaller pieces to release whey, a process known as curdling. The size of the curd pieces determines the cheese’s final moisture content: smaller pieces expel more whey, resulting in harder cheeses like cheddar, while larger pieces retain moisture for softer varieties like mozzarella. Curd cutting requires precision—too aggressive, and the curds may break; too gentle, and whey drainage is insufficient. After cutting, the curds are stirred and heated to expel more whey, a step called "scalding," which further firms the texture.

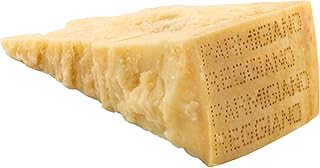

Pressing follows curdling, where the curds are consolidated into a cohesive mass. Pressure is applied to remove remaining whey and compact the curds. For semi-hard cheeses like Gruyère, moderate pressure is applied for several hours, while hard cheeses like Parmesan may be pressed under heavy weights for a day or more. Pressing also shapes the cheese, whether in molds or free-form. Proper pressing ensures uniformity and prevents cracks or voids in the final product.

The final transformation occurs during aging, where cheese develops its distinctive flavor, texture, and aroma. Aging times vary widely: fresh cheeses like ricotta are ready in days, while aged cheeses like Gouda or blue cheese can mature for months or even years. During aging, bacteria and molds break down proteins and fats, creating complex flavors. Humidity and temperature control are critical—ideally, 50–60% humidity and 50–55°F (10–13°C) for most cheeses. Regular flipping and brushing of the rind prevent mold overgrowth and ensure even development.

Together, these steps showcase the alchemy of cheesemaking, where milk is meticulously transformed through coagulation, curdling, pressing, and aging. Each phase demands attention to detail, from enzyme dosages to environmental conditions, but the reward is a product rich in flavor and history. Whether crafting a simple farmhouse cheese or a complex aged variety, the process remains a testament to human ingenuity and the magic of fermentation.

Creative Mouse Trapping: Cheese-Free Strategies to Catch Pesky Rodents Fast

You may want to see also

Milk-to-Cheese Ratio: Approximately 10 pounds of milk yields 1 pound of cheese

Cheese is indeed a product of milk, but the transformation from liquid to solid is a fascinating process of concentration and coagulation. One of the most striking aspects of this transformation is the milk-to-cheese ratio, which reveals just how much milk is required to produce a single pound of cheese. Approximately 10 pounds of milk yields 1 pound of cheese, a ratio that underscores the efficiency and complexity of cheesemaking. This means that for every gallon of milk (roughly 8.6 pounds), you can expect to produce less than a pound of cheese, depending on the type.

Consider the implications of this ratio for both home cheesemakers and commercial producers. For a small-scale enthusiast, understanding this ratio is crucial for planning. If you aim to make a 2-pound block of cheddar, you’ll need about 20 pounds of milk—a volume that requires careful handling and space. Commercial producers, on the other hand, must manage this ratio at scale, often processing thousands of pounds of milk daily. The milk-to-cheese ratio directly impacts production costs, waste management, and resource allocation, making it a cornerstone of the dairy industry.

From a nutritional perspective, this ratio highlights the concentration of milk’s components in cheese. Milk is primarily water, but cheese is a dense, nutrient-rich food. For example, 10 pounds of whole milk contains roughly 32 grams of protein, while 1 pound of cheddar cheese contains about 25 grams of protein. This concentration means cheese provides a more calorie-dense and protein-rich option, but it also amplifies fat and sodium content. For those monitoring their diet, understanding this ratio helps in making informed choices about portion sizes and nutritional intake.

Practical tips for working with this ratio include selecting the right type of milk for cheesemaking. Not all milk is created equal; raw milk, pasteurized milk, and homogenized milk behave differently during the cheesemaking process. Raw milk, for instance, often yields a higher-quality cheese due to its intact enzymes and bacteria, but it requires careful handling to avoid contamination. Additionally, the fat content of the milk affects the final product—whole milk produces richer, creamier cheeses, while skim milk results in leaner, firmer varieties. Experimenting with different milks and tracking the yield based on the 10:1 ratio can help refine your cheesemaking skills.

Finally, the milk-to-cheese ratio serves as a reminder of the artistry and science behind cheesemaking. It’s not merely a mechanical process but a delicate balance of temperature, acidity, and time. For instance, soft cheeses like mozzarella require less milk per pound compared to hard cheeses like Parmesan, which can take up to 12 pounds of milk per pound of cheese. This variation adds depth to the craft, encouraging cheesemakers to explore different techniques and recipes. Whether you’re a novice or an expert, mastering this ratio is key to creating cheese that’s both delicious and consistent.

Mastering the Taco Bell App: Ordering Pintos and Cheese Like a Pro

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Non-Dairy Alternatives: Plant-based cheeses use nuts, soy, or coconut milk instead of dairy

Cheese traditionally comes from milk, but not all cheese adheres to this rule. Plant-based cheeses challenge this norm by using nuts, soy, or coconut milk as their base. These alternatives cater to vegans, lactose-intolerant individuals, and those seeking diverse dietary options. Unlike dairy cheese, which relies on milk curdling and aging, plant-based versions often involve fermentation, culturing, or blending to achieve texture and flavor. For instance, cashew-based cheeses mimic creaminess, while soy-based options offer a firmer, sliceable consistency. This innovation proves that cheese doesn’t require milk to exist—it simply requires creativity.

To make plant-based cheese at home, start with a nut or seed base like cashews, almonds, or sunflower seeds. Soak them for 4–6 hours to soften, then blend with probiotic capsules, nutritional yeast, and salt. Let the mixture ferment for 24–48 hours at room temperature to develop tanginess. For a quicker option, skip fermentation and add lemon juice or apple cider vinegar for acidity. Shape the mixture into rounds or logs, then refrigerate for 12–24 hours to firm up. Experiment with herbs, spices, or smoked flavors to customize your cheese. This DIY approach ensures control over ingredients and avoids additives found in store-bought versions.

From a nutritional standpoint, plant-based cheeses often rival dairy counterparts. For example, almond-based cheeses provide healthy fats and vitamin E, while soy-based options offer complete protein. However, they typically contain fewer probiotics than aged dairy cheeses, so pairing them with fermented foods like sauerkraut can enhance gut health. Be mindful of sodium content, as some brands add salt for flavor. For those with nut allergies, coconut milk-based cheeses are a safe alternative, rich in medium-chain triglycerides. Always check labels for added sugars or preservatives, especially in flavored varieties.

Comparing plant-based and dairy cheeses reveals distinct advantages and trade-offs. Dairy cheese boasts a complex flavor profile developed through aging, while plant-based versions often rely on added ingredients to mimic taste. However, plant-based cheeses are more sustainable, requiring fewer resources and producing fewer greenhouse gases. Melting properties differ too: dairy cheeses melt smoothly due to milk fats, whereas plant-based cheeses may need starches or oils to achieve a similar effect. Ultimately, the choice depends on dietary needs, environmental concerns, and personal preference. Both types have their place in a diverse culinary landscape.

What Bird Says Burger Cheese Burger Cheese Burger? Unraveling the Mystery

You may want to see also

Nutritional Differences: Cheese retains milk's protein and calcium but has higher fat and calories

Cheese, a beloved staple in diets worldwide, is indeed a product of milk, but its nutritional profile diverges significantly from its liquid precursor. While both share essential nutrients, the transformation process concentrates certain elements while amplifying others. For instance, a single cup of whole milk contains approximately 8 grams of protein and 276 mg of calcium, whereas an equivalent weight of cheddar cheese boasts 25 grams of protein and 307 mg of calcium. This concentration occurs because cheese is made by curdling milk, removing much of its whey, which contains water and lactose, leaving behind a denser matrix of fats, proteins, and minerals.

From a dietary perspective, this transformation has practical implications. For individuals aiming to increase protein intake, cheese offers a more efficient source compared to milk. A 30-gram serving of cheddar provides 7 grams of protein, nearly equivalent to a cup of milk but in a much smaller portion. However, this convenience comes with a trade-off: the same serving of cheddar contains 120 calories and 9 grams of fat, compared to 150 calories and 8 grams of fat in a cup of whole milk. For those monitoring calorie or fat intake, this disparity underscores the importance of portion control when incorporating cheese into meals.

Children and adolescents, who require higher calcium intake for bone development, can benefit from cheese’s concentrated mineral content. A single ounce of Swiss cheese provides 27% of the daily calcium recommendation for a 9- to 13-year-old, making it an appealing option for picky eaters. However, parents should balance this with awareness of cheese’s sodium content—that same ounce contains 80 mg of sodium, contributing to daily limits that should not exceed 2,300 mg for most age groups. Pairing cheese with low-sodium foods, such as fresh fruits or vegetables, can mitigate this concern.

For adults, particularly those managing weight or cardiovascular health, the fat content in cheese demands attention. Opting for low-fat varieties, such as part-skim mozzarella or cottage cheese, can reduce saturated fat intake without sacrificing protein or calcium. For example, 100 grams of full-fat cheddar contains 33 grams of fat, while the same portion of part-skim mozzarella contains 17 grams. Incorporating cheese into meals strategically—such as using it as a flavor enhancer rather than a main ingredient—can maximize its nutritional benefits while minimizing drawbacks.

Ultimately, understanding cheese’s nutritional differences from milk empowers informed dietary choices. While it retains milk’s protein and calcium, its higher fat and calorie content necessitates mindful consumption. By selecting appropriate varieties, controlling portions, and pairing cheese with complementary foods, individuals can harness its nutritional strengths while navigating its challenges. Whether for bone health, muscle repair, or culinary enjoyment, cheese’s unique profile makes it a versatile yet nuanced addition to any diet.

Easy Steps to Replace the Wire on Your Wood Cheese Board

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, cheese is made from milk, typically from cows, goats, sheep, or buffalo.

The process involves curdling milk using enzymes (like rennet) or acids, separating the curds (solids) from the whey (liquid), and then pressing and aging the curds to create cheese.

Yes, non-dairy cheese can be made from plant-based milks like soy, almond, or cashew, though it is not considered traditional cheese and has a different texture and flavor.

Cheese undergoes fermentation and aging, which transforms the milk’s proteins and fats, creating complex flavors, textures, and aromas that differ from the original milk.