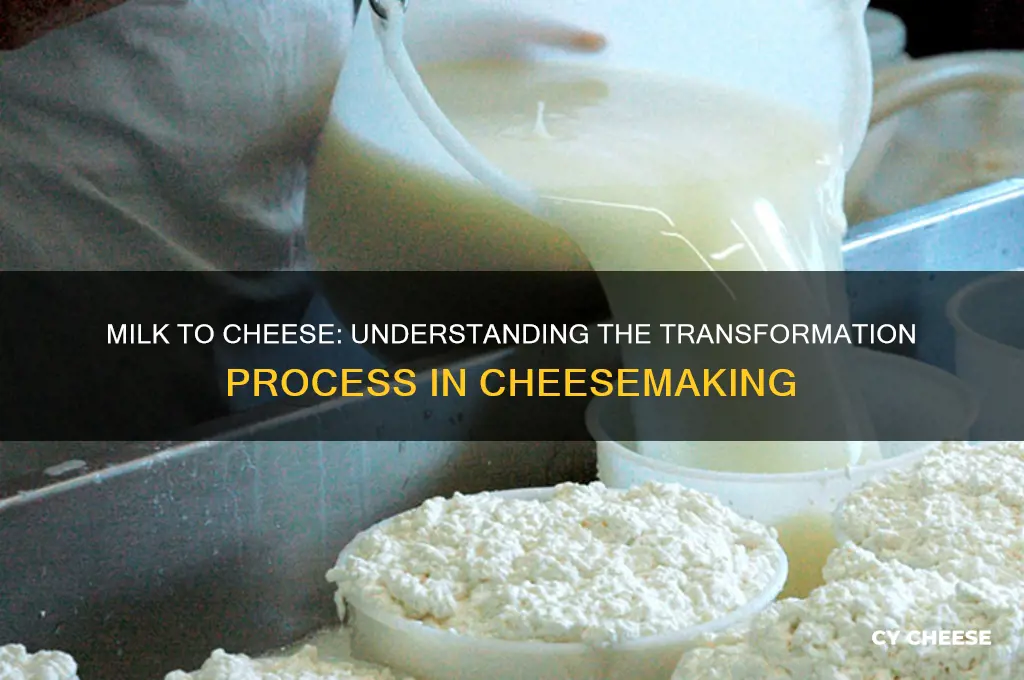

The transformation of milk into cheese is a fascinating process rooted in ancient culinary traditions. At its core, cheese-making involves curdling milk, typically through the addition of bacteria or acids, which causes it to separate into solid curds and liquid whey. These curds are then pressed, aged, and often treated with enzymes or molds to develop flavor, texture, and complexity. While milk itself is a simple, liquid dairy product, the journey to cheese showcases the remarkable alchemy of fermentation and craftsmanship, turning a basic ingredient into a diverse array of cheeses enjoyed worldwide.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Process | Milk is transformed into cheese through a process called coagulation, where milk proteins (casein) are curdled using rennet or acid, separating into curds (solids) and whey (liquid). |

| Key Ingredients | Milk (cow, goat, sheep, or buffalo), coagulants (rennet or acids like vinegar/lemon juice), bacteria cultures, and salt. |

| Time Required | Varies by cheese type: fresh cheeses (e.g., ricotta) take hours, while aged cheeses (e.g., cheddar) take weeks to years. |

| Role of Bacteria | Bacteria cultures ferment lactose into lactic acid, lowering pH and aiding curd formation; also contribute to flavor and texture. |

| Role of Rennet | Enzyme complex that coagulates milk proteins, forming a firmer curd; alternatives include microbial or plant-based rennets. |

| Whey Separation | Whey is drained off, leaving behind curds that are pressed, shaped, and aged to become cheese. |

| Aging Process | Aging develops flavor, texture, and complexity; duration and conditions (temperature, humidity) vary by cheese type. |

| Types of Cheese | Fresh (ricotta, mozzarella), soft (brie, camembert), semi-hard (cheddar, gouda), hard (parmesan, pecorino). |

| Nutritional Changes | Cheese is more concentrated in protein, fat, and calcium compared to milk; lactose content is reduced during fermentation. |

| Preservation | Cheese is a preserved form of milk, with a longer shelf life due to reduced moisture and increased acidity/salinity. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Milk Coagulation Process: Enzymes or acids curdle milk, separating solids (curds) from liquids (whey)

- Role of Bacteria: Starter cultures ferment milk, producing lactic acid essential for cheese formation

- Curd Formation: Curds are pressed and cut to release whey, shaping cheese texture

- Aging and Ripening: Time and conditions develop flavor, texture, and aroma in cheese

- Types of Cheese: Variations in milk, bacteria, and processing create diverse cheese varieties

Milk Coagulation Process: Enzymes or acids curdle milk, separating solids (curds) from liquids (whey)

Milk does not spontaneously turn into cheese; it requires a deliberate process that begins with coagulation. This transformation hinges on the separation of milk into solids (curds) and liquids (whey), a reaction triggered by enzymes or acids. Rennet, a complex of enzymes derived from animal stomachs, is the traditional catalyst, but microbial transglutaminase and plant-based coagulants like fig tree bark extract offer modern alternatives. Acidification, using vinegar or citric acid, is another method, though it yields a denser, crumbly curd often used in cheeses like paneer or queso blanco. Understanding these agents and their mechanisms is the first step in mastering the art of cheese making.

The coagulation process is both a science and an art, requiring precision in temperature and dosage. For rennet, a typical dosage ranges from 0.02% to 0.05% of the milk’s weight, added after heating the milk to 30–35°C (86–95°F). Acid coagulation is faster but less forgiving; adding 1–2 tablespoons of vinegar or diluted citric acid to a gallon of milk at 18–20°C (64–68°F) will yield curds within minutes. However, over-acidification can result in a tough, rubbery texture. Monitoring pH levels—aiming for a drop to around 4.6—ensures optimal curd formation. This step is critical, as it sets the foundation for the cheese’s texture, flavor, and yield.

Comparing enzymatic and acid coagulation reveals distinct advantages and limitations. Enzymes produce a softer, more elastic curd ideal for aged cheeses like cheddar or gouda, while acids create a firmer, more brittle curd suited for fresh cheeses. Enzymatic coagulation also allows for slower, more controlled curd formation, preserving milk proteins and fats. Acid coagulation, though quicker, can lead to whey retention in the curd, affecting moisture content and shelf life. Choosing the right method depends on the desired cheese type and the maker’s equipment and time constraints.

Practical tips can streamline the coagulation process for home cheese makers. Always use non-ultra-pasteurized milk, as high heat treatment denatures proteins essential for curdling. For consistent results, invest in a thermometer and pH meter to monitor temperature and acidity. When using rennet, dilute it in cool, non-chlorinated water before adding to milk to ensure even distribution. For acid coagulation, add the acid gradually, stirring gently until the milk separates. Finally, allow the curds to rest for 5–10 minutes before cutting or draining to expel excess whey. These steps ensure a successful coagulation, paving the way for a delicious final product.

Condensed Milk's Role in Setting No-Bake Cheesecake: A Sweet Science

You may want to see also

Role of Bacteria: Starter cultures ferment milk, producing lactic acid essential for cheese formation

Milk does not spontaneously transform into cheese; it requires the intervention of specific bacteria known as starter cultures. These microorganisms are the unsung heroes of cheesemaking, initiating a complex process that turns liquid milk into a solid, flavorful cheese. The primary role of these bacteria is to ferment lactose, the natural sugar in milk, into lactic acid. This fermentation is a critical step, as lactic acid lowers the milk’s pH, causing it to curdle and expel whey, the liquid byproduct. Without this bacterial action, milk would remain in its liquid state, devoid of the structure and texture we associate with cheese.

To understand the process, consider the precision required in selecting and adding starter cultures. Common bacteria used include *Lactococcus lactis*, *Streptococcus thermophilus*, and *Lactobacillus bulgaricus*, each contributing unique characteristics to the cheese. The dosage of these cultures is crucial—typically, 1-2% of the milk volume is inoculated with the starter culture. Too little, and fermentation may be incomplete; too much, and the flavor can become overly acidic. Temperature control is equally vital, as these bacteria thrive in specific ranges (e.g., mesophilic cultures at 20-40°C, thermophilic cultures at 40-45°C). This step is not just science; it’s an art, requiring careful monitoring to achieve the desired outcome.

The production of lactic acid serves multiple purposes beyond curdling. It acts as a natural preservative, inhibiting the growth of harmful bacteria and extending the cheese’s shelf life. Additionally, lactic acid influences the cheese’s flavor profile, contributing tangy or sharp notes depending on the culture used. For example, cheddar relies on *Lactococcus lactis* for its characteristic sharpness, while mozzarella benefits from the milder action of *Streptococcus thermophilus*. This diversity highlights how the choice of starter culture can dramatically alter the final product, making it a key decision in the cheesemaker’s process.

Practical tips for home cheesemakers emphasize the importance of consistency. Always use high-quality, fresh milk to ensure optimal bacterial activity. Sterilize equipment to prevent contamination from unwanted microorganisms. When adding starter cultures, mix thoroughly but gently to avoid damaging the bacteria. Monitor pH levels during fermentation; a drop from 6.6 to 5.0 indicates successful curdling. Finally, experiment with different cultures to explore the range of flavors and textures achievable. By mastering the role of bacteria, even novice cheesemakers can transform simple milk into a complex, delicious cheese.

Does DQ Serve Cheese Curds? Exploring Dairy Queen's Menu Offerings

You may want to see also

Curd Formation: Curds are pressed and cut to release whey, shaping cheese texture

Milk's transformation into cheese hinges on curd formation, a delicate dance of coagulation and separation. When rennet or acid is introduced, milk proteins (casein) clump together, forming a gelatinous mass called curd. This curd, suspended in a watery liquid called whey, holds the potential for countless cheese varieties.

Imagine a pot of gently warmed milk, its surface rippling as rennet is added. Within minutes, the liquid transforms. A soft, custard-like curd emerges, distinct from the thin, greenish whey. This is the pivotal moment where milk ceases to be milk and becomes the foundation of cheese. The curd's texture at this stage is crucial; too firm, and the cheese will be dense, too soft, and it may lack structure.

The next step is where artistry meets science: cutting and pressing. The curd is carefully sliced into smaller pieces, releasing more whey and determining the cheese's final texture. Larger curds, gently handled, create open, crumbly cheeses like cheddar. Smaller cuts and vigorous stirring yield smoother, denser cheeses like mozzarella. Pressing further expels whey, concentrating the curd and shaping the cheese's form. A gentle press might create a soft, spreadable cheese, while intense pressure results in hard, aged varieties like Parmesan.

This process is not merely mechanical; it's a delicate balance. Over-cutting or excessive pressing can lead to a dry, crumbly texture. Insufficient whey removal can cause spoilage. The cheesemaker's skill lies in understanding the curd's unique characteristics and guiding its transformation with precision.

Mastering curd formation is the key to unlocking the vast world of cheese. From the creamy indulgence of Brie to the sharp tang of cheddar, each cheese's personality is born in the careful manipulation of curds and whey. This ancient practice, refined over centuries, continues to inspire innovation, proving that even the simplest ingredients can yield extraordinary results.

Refrigerating Cheese and Sausage Gifts: Essential Tips for Freshness

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$52.99

Aging and Ripening: Time and conditions develop flavor, texture, and aroma in cheese

Milk's transformation into cheese is a fascinating process, but it's during aging and ripening that the magic truly happens. These stages are where a simple cheese becomes a complex, flavorful masterpiece. Imagine a young, mild cheddar evolving into a sharp, crumbly delight over months or even years. This maturation process is an art, a delicate dance of time and environmental factors that unlock a cheese's full potential.

The Science of Ripening:

Cheese aging is a biological process primarily driven by bacteria and enzymes. When cheese is first made, it contains a variety of microorganisms, some of which remain active during aging. These bacteria continue to break down the cheese's proteins and fats, releasing various compounds that contribute to flavor development. For instance, propionic bacteria in Swiss cheese produce carbon dioxide gas, creating the characteristic eyes (holes) and a nutty flavor. The longer a cheese ages, the more these bacteria work their magic, intensifying flavors and transforming textures.

Time and Temperature:

Aging cheese is a waiting game, but it's not just about duration. Temperature and humidity play critical roles. Most cheeses are aged in controlled environments, with specific temperature ranges for different varieties. For example, hard cheeses like Parmesan are typically aged at 10-15°C (50-59°F), while soft-ripened cheeses like Camembert prefer a cooler 10-12°C (50-54°F). The aging time varies widely, from a few weeks for fresh cheeses to several years for aged cheddar or Gouda. During this period, regular turning and caring for the cheese are essential to ensure even moisture distribution and prevent mold growth.

Aging Techniques and Flavors:

Cheesemakers employ various techniques to influence the aging process. One method is washing the cheese rind with brine, wine, or beer, which encourages the growth of specific bacteria and molds, adding unique flavors. For instance, washed-rind cheeses like Epoisses have a distinctive pungent aroma and a creamy texture due to the specific bacteria encouraged by this process. Another technique is smoking, which imparts a smoky flavor and can also act as a preservative. The art of aging also involves knowing when to stop—over-aging can lead to an overly sharp taste and dry texture.

The Art of Affinage:

In the world of cheese, 'affinage' refers to the skilled art of aging and ripening. Affineurs are experts who carefully monitor and control the aging process, often in specialized caves or cellars. They regularly inspect and care for the cheeses, ensuring optimal conditions for each variety. This craft involves understanding the unique characteristics of different cheeses and knowing how to bring out their best qualities. For instance, an affineur might wrap a young cheese in cloth to encourage mold growth, then carefully remove it at the right moment to achieve the desired flavor and texture.

In the journey from milk to cheese, aging and ripening are the transformative phases that elevate a simple dairy product to a gourmet delight. It's a process that requires patience, precision, and a deep understanding of the science and art of cheesemaking. The next time you savor a piece of aged cheese, consider the months or years of careful maturation that have gone into creating its distinctive flavor, texture, and aroma.

Does Cheese Cause Urine Odor? Unraveling the Smelly Mystery

You may want to see also

Types of Cheese: Variations in milk, bacteria, and processing create diverse cheese varieties

Milk's transformation into cheese is a fascinating journey, hinging on the interplay of three key variables: milk type, bacterial cultures, and processing techniques. Each element contributes uniquely, crafting the vast spectrum of cheeses we savor. Consider the milk source—cow, goat, sheep, or even buffalo—each imparts distinct flavors and textures. Cow’s milk, rich in fat and protein, forms the basis for classics like cheddar and mozzarella. Goat’s milk, with its tangy undertones, yields sharp, crumbly varieties such as chèvre. Sheep’s milk, higher in fat, creates indulgent options like pecorino or manchego. Buffalo milk, though less common, produces creamy, luxurious cheeses like mozzarella di bufala.

Bacterial cultures act as the silent artisans, fermenting lactose into lactic acid and shaping flavor profiles. Mesophilic cultures thrive in lower temperatures, crafting softer cheeses like brie or camembert. Thermophilic cultures, heat-loving, are essential for harder cheeses such as parmesan or gruyère. The type and quantity of bacteria determine acidity, aroma, and texture. For instance, adding *Penicillium camemberti* introduces the signature white rind on camembert, while *Propionibacterium freudenreichii* creates the eye-catching holes in Swiss cheese.

Processing techniques further diversify cheese varieties, from curdling and pressing to aging and smoking. Curdling methods—using rennet, acid, or heat—dictate moisture content and structure. Fresh cheeses like ricotta or paneer involve minimal processing, retaining softness. Hard cheeses undergo prolonged pressing and aging, developing complex flavors and firm textures. Aging time varies dramatically: a young cheddar matures in 2–3 months, while a parmesan wheel ages for over a year. Smoking, brining, or washing the rind adds layers of flavor, as seen in smoky gouda or pungent limburger.

Practical tip: Experiment with DIY cheese-making to grasp these variables. Start with a simple recipe like paneer—heat whole milk, add lemon juice, drain the curds, and press. For a bolder project, try making mozzarella by stretching curds in hot water. Always use high-quality milk and precise temperature control for consistent results. Understanding these processes not only deepens appreciation for cheese but also empowers creativity in the kitchen.

The takeaway? Cheese diversity is no accident—it’s a deliberate dance of milk, bacteria, and technique. Each choice, from the animal’s diet to the aging environment, leaves an indelible mark. Next time you slice into a wedge, consider the intricate science behind its creation. It’s not just food; it’s a testament to human ingenuity and nature’s bounty.

Daily Work Hours for Cheese Workers: Understanding the Average Time

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, milk does not directly turn into cheese. It undergoes a process involving the addition of bacteria, rennet, and other enzymes to curdle and separate into curds and whey, which are then processed into cheese.

Yes, various types of milk, including cow, goat, sheep, and even buffalo milk, can be used to make cheese. The type of milk affects the flavor, texture, and characteristics of the final product.

The time varies depending on the type of cheese. Some fresh cheeses, like ricotta, can be made in a few hours, while aged cheeses, such as cheddar or parmesan, can take weeks, months, or even years to fully develop.

The process is natural, relying on biological reactions from bacteria, enzymes, and fermentation. However, modern cheese-making often includes controlled conditions and additives to ensure consistency and safety.

![Artisan Cheese Making at Home: Techniques & Recipes for Mastering World-Class Cheeses [A Cookbook]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/81eH1+cYeZL._AC_UL320_.jpg)