The question of whether real cheese burns is a common curiosity, especially among cooking enthusiasts and cheese lovers. When exposed to heat, cheese undergoes a transformation—melting, browning, and eventually burning if left unattended. Real cheese, made from milk and without additives, behaves differently than processed varieties, as its natural fats and proteins react uniquely to high temperatures. Understanding this process not only enhances culinary skills but also sheds light on the science behind one of the world’s most beloved ingredients. Whether you’re grilling, baking, or simply toasting, knowing how and when real cheese burns can elevate your dishes and prevent kitchen mishaps.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Does Real Cheese Burn? | Yes, real cheese can burn when exposed to high heat for prolonged periods. |

| Burning Temperature | Typically starts to burn at around 150°C (302°F) or higher, depending on the type of cheese. |

| Appearance When Burned | Turns brown or black, becomes hard and crispy, and may develop a bitter taste. |

| Factors Affecting Burning | Type of cheese (hard cheeses burn faster), moisture content, fat content, and cooking method. |

| Common Cooking Methods Leading to Burning | Grilling, broiling, frying, or overheating in an oven or pan. |

| Prevention Tips | Use low to medium heat, monitor closely, and avoid direct high heat for extended periods. |

| Health Impact of Burned Cheese | May produce harmful compounds like acrylamide, though occasional consumption is unlikely to cause significant harm. |

| Alternative Cooking Methods | Melting cheese slowly over low heat, using a double boiler, or adding liquids to prevent direct heat exposure. |

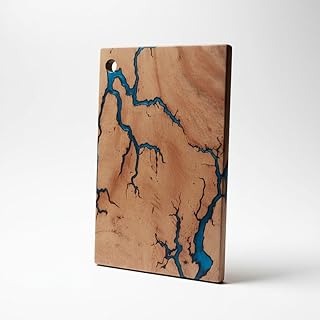

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Melting vs. Burning

Cheese, when exposed to heat, undergoes a transformation that can be both delightful and disastrous, depending on the outcome. The key to understanding this process lies in distinguishing between melting and burning. Melting is a controlled, desirable change where cheese softens and becomes creamy, ideal for dishes like grilled cheese or fondue. Burning, however, is an irreversible process where the cheese darkens, hardens, and loses its flavor, often due to excessive heat or prolonged exposure. Recognizing the difference is crucial for culinary success.

To achieve perfect melting, consider the cheese’s moisture content and melting point. High-moisture cheeses like mozzarella melt smoothly at around 130°F to 150°F, making them ideal for pizzas. Low-moisture cheeses like cheddar require higher temperatures (150°F to 180°F) but can separate if overheated. Always use low to medium heat and stir gently to distribute heat evenly. For example, when making a cheese sauce, combine grated cheese with a roux over low heat to prevent graininess or scorching.

Burning occurs when cheese exceeds its smoke point, typically around 350°F to 400°F. This is why leaving cheese unattended in a hot pan or under a broiler often leads to disaster. Practical tips to avoid burning include using a thermometer to monitor temperature, adding a splash of milk or cream to regulate heat, and opting for indirect heat methods like baking or steaming. For instance, when making cheese crisps, preheat the oven to 375°F and bake for 5–7 minutes, watching closely to ensure they brown without burning.

The science behind melting vs. burning lies in the cheese’s protein and fat composition. During melting, proteins unwind and fats liquefy, creating a smooth texture. Burning, however, causes proteins to denature and fats to oxidize, resulting in a bitter taste and hardened texture. Understanding this chemistry allows you to manipulate heat effectively. For example, adding acid (like lemon juice) can help stabilize proteins and prevent separation, but it won’t stop burning if the temperature is too high.

In practice, the line between melting and burning is thin but manageable with attention to detail. Always start with smaller quantities of cheese to test heat levels, especially when using new equipment or recipes. For advanced techniques like flame-grilled halloumi, which has a high melting point (around 200°F), ensure the grill is hot but not scorching to achieve char marks without burning. Ultimately, mastering the art of melting while avoiding burning elevates cheese from a simple ingredient to a culinary masterpiece.

Taco Bell's 3 Cheese Blend: Ingredients and Flavor Profile Revealed

You may want to see also

Cheese Types & Burn Rates

Real cheese does burn, but not all cheeses char at the same rate or in the same way. The burn rate of cheese is influenced by its moisture content, fat composition, and protein structure. Hard, low-moisture cheeses like Parmesan or Pecorino Romano are more likely to brown and crisp up quickly due to their dense, dry texture, making them ideal for topping dishes like pasta or salads where a crunchy, nutty flavor is desired. On the other hand, high-moisture cheeses like mozzarella or fresh goat cheese tend to melt rather than burn, as their water content evaporates before the proteins and fats can significantly char. Understanding these differences allows you to control how cheese behaves under heat, whether you’re grilling, broiling, or baking.

For those aiming to achieve a perfect golden crust on their cheese, consider the cooking method and temperature. Hard cheeses can withstand higher temperatures (around 400°F or 200°C) for shorter periods, creating a desirable browning effect without burning. Soft cheeses, however, require lower temperatures (around 350°F or 175°C) and should be monitored closely to avoid overcooking. A practical tip is to use a kitchen thermometer to gauge the internal temperature of the dish, ensuring the cheese reaches its melting point (typically 130°–150°F or 55°–65°C) without exceeding it. This precision prevents the proteins from toughening and the fats from scorching, preserving both texture and flavor.

Comparing cheese burn rates reveals fascinating insights into their culinary applications. For instance, semi-hard cheeses like cheddar or Gruyère strike a balance between moisture and fat, allowing them to melt smoothly while developing a slight brown crust when exposed to heat. This makes them versatile for dishes like grilled cheese sandwiches or cheese plates. In contrast, blue cheeses like Gorgonzola or Roquefort have a higher fat content and lower melting point, making them prone to burning if not handled carefully. These cheeses are best used as finishing touches, added at the end of cooking to preserve their complex flavors and creamy texture.

To maximize the burn rate of cheese for specific recipes, consider blending different types. For example, combining a hard cheese like Asiago with a softer cheese like Brie can create a layered effect where the hard cheese crisps up while the soft cheese melts underneath. This technique is particularly effective in dishes like flatbreads or casseroles. Additionally, adding a small amount of acid (like a splash of lemon juice or wine) can slow down the browning process, giving you more control over the final result. Experimenting with these combinations and techniques will help you harness the unique burn rates of cheeses to elevate your cooking.

Cooper Cheese in Wooden Boxes: A Historical Packaging Journey

You may want to see also

Ideal Cooking Temperatures

Real cheese, unlike processed varieties, has a delicate balance of moisture, fat, and protein that reacts uniquely to heat. Understanding ideal cooking temperatures is crucial for achieving desired textures—melty, crispy, or browned—without burning. For gentle melting, such as in a grilled cheese or fondue, aim for 120°F to 150°F (49°C to 65°C). This range preserves the cheese’s structure while allowing it to soften evenly. A kitchen thermometer can ensure precision, especially when working with high-moisture cheeses like mozzarella or brie.

When browning is the goal, as in a cheese crisp or au gratin, temperatures must rise to 350°F to 400°F (177°C to 204°C). At this level, the Maillard reaction occurs, creating a golden crust and deeper flavor. However, monitor closely—hard cheeses like Parmesan or cheddar brown faster than softer varieties. Preheating the cooking surface or oven is essential to avoid uneven results. For crispy toppings, broil for 1–2 minutes, but stay vigilant; the line between browned and burned is thin.

Not all cheeses are created equal in heat tolerance. Fresh cheeses like ricotta or goat cheese curdle and separate above 170°F (77°C), making them unsuitable for high-heat applications. Semi-hard cheeses like Gruyère or provolone excel in dishes requiring prolonged heat, such as casseroles or lasagnas, where temperatures hover around 350°F (177°C). Pairing cheeses with complementary melting points—like combining a stretchy mozzarella with a sharp cheddar—can enhance texture and flavor in mixed-cheese dishes.

Mastering ideal cooking temperatures for real cheese requires experimentation and attention to detail. Start with low heat, gradually increasing as needed, and always preheat your cooking vessel. For baked dishes, tent with foil to prevent excessive browning while cooking through. Remember, the goal is to control the transformation of cheese under heat, not to rush it. With practice, you’ll instinctively know when to dial back the temperature or pull the dish from the oven, ensuring perfect results every time.

Protein Content in Havarti Cheese: A Nutritional Breakdown

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Signs of Burnt Cheese

Real cheese, when subjected to heat, undergoes a transformation that can be both delightful and disastrous. The line between perfectly melted and burnt is thin, and recognizing the signs of burnt cheese is crucial for any culinary enthusiast. The first indicator is a change in color: cheese that has burnt will often develop dark brown or black spots, a stark contrast to its usual golden hue. This visual cue is immediate and unmistakable, serving as a warning that the cheese has been exposed to excessive heat for too long.

Beyond appearance, the texture of burnt cheese tells a story of its own. Instead of maintaining a smooth, creamy consistency, it becomes tough, rubbery, or even crispy around the edges. This textural shift is a result of the proteins and fats breaking down under high temperatures, leading to an irreversible change in structure. For example, a grilled cheese sandwich left unattended on a skillet will exhibit a hard, almost brittle exterior, while the interior loses its desirable stretchiness.

Aromatically, burnt cheese emits a sharp, acrid smell that overpowers its natural, mild fragrance. This odor is a byproduct of the Maillard reaction gone awry, where sugars and amino acids react excessively, producing unpleasant compounds. If you notice a pungent, chemical-like scent wafting from your cheese, it’s a clear sign that it has crossed the threshold from cooked to burnt. This sensory cue is particularly useful when you can’t visually inspect the cheese, such as when it’s baked inside a dish.

To avoid burnt cheese, monitor cooking temperatures and times meticulously. For instance, when melting cheese in a sauce, keep the heat low and stir constantly to distribute warmth evenly. If using an oven, preheat it to no more than 350°F (175°C) and check the dish frequently after the 10-minute mark. For grilled applications, use medium heat and flip the item regularly to prevent direct, prolonged exposure to the heat source. By staying vigilant and understanding these signs, you can preserve the integrity of real cheese in every dish.

Missing Citric Acid in Cheese: Consequences and How to Fix It

You may want to see also

Preventing Cheese from Burning

Cheese, a culinary staple, can indeed burn, especially when exposed to high heat for prolonged periods. The proteins and fats in cheese react differently to heat, leading to a fine line between melted perfection and a charred mess. Understanding this behavior is the first step in preventing cheese from burning. For instance, hard cheeses like Parmesan have a higher burning point compared to soft cheeses like Brie, which can scorch quickly under direct heat.

To prevent cheese from burning, consider the cooking method and temperature. When melting cheese on a stovetop, use low to medium heat and stir constantly. This ensures even heat distribution and prevents hot spots that can cause burning. For example, when making a cheese sauce, start with a roux and gradually add milk and cheese, keeping the heat steady and avoiding rapid boiling. If using a microwave, heat the cheese in short intervals (15–20 seconds) and stir between each session to maintain control over the melting process.

Another effective strategy is to incorporate moisture barriers. Adding a small amount of liquid, such as milk, cream, or wine, can help regulate the temperature and prevent the cheese from drying out and burning. For instance, when making a grilled cheese sandwich, brushing the bread with butter instead of placing it directly in a hot pan can create a protective layer, allowing the cheese to melt evenly without burning the bread. Similarly, when baking dishes like lasagna or casseroles, cover them with foil for the first half of the cooking time to trap moisture and prevent the cheese topping from burning.

Choosing the right type of cheese for the cooking method is also crucial. Hard and semi-hard cheeses like Cheddar, Gruyère, and Mozzarella are more forgiving and less likely to burn compared to soft or fresh cheeses. For high-heat applications like grilling or broiling, opt for cheeses with higher melting points, such as Halloumi or Provolone. Conversely, reserve delicate cheeses like goat cheese or cream cheese for low-heat dishes or as finishing touches to avoid scorching.

Finally, monitor the cooking process closely. Even with the best precautions, cheese can burn if left unattended. Use a timer and visually inspect the cheese regularly, especially when broiling or grilling. If you notice browning or bubbling, reduce the heat or move the dish further from the heat source. For baked dishes, rotate the pan halfway through cooking to ensure even heat exposure. By combining these techniques—controlling heat, adding moisture, selecting appropriate cheeses, and vigilant monitoring—you can master the art of melting cheese without burning it.

Cheese Straws Without Eggs: Essential or Optional in Your Recipe?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, real cheese can burn if exposed to high heat for too long, especially when it’s not monitored or cooked properly.

Real cheese typically starts to burn at temperatures above 350°F (177°C), depending on the type and moisture content of the cheese.

To prevent burning, use medium heat, monitor closely, and avoid leaving cheese unattended. Adding a small amount of liquid or using a non-stick pan can also help.

Yes, real cheese tends to burn faster than processed cheese because it lacks the additives and stabilizers that make processed cheese more heat-resistant.