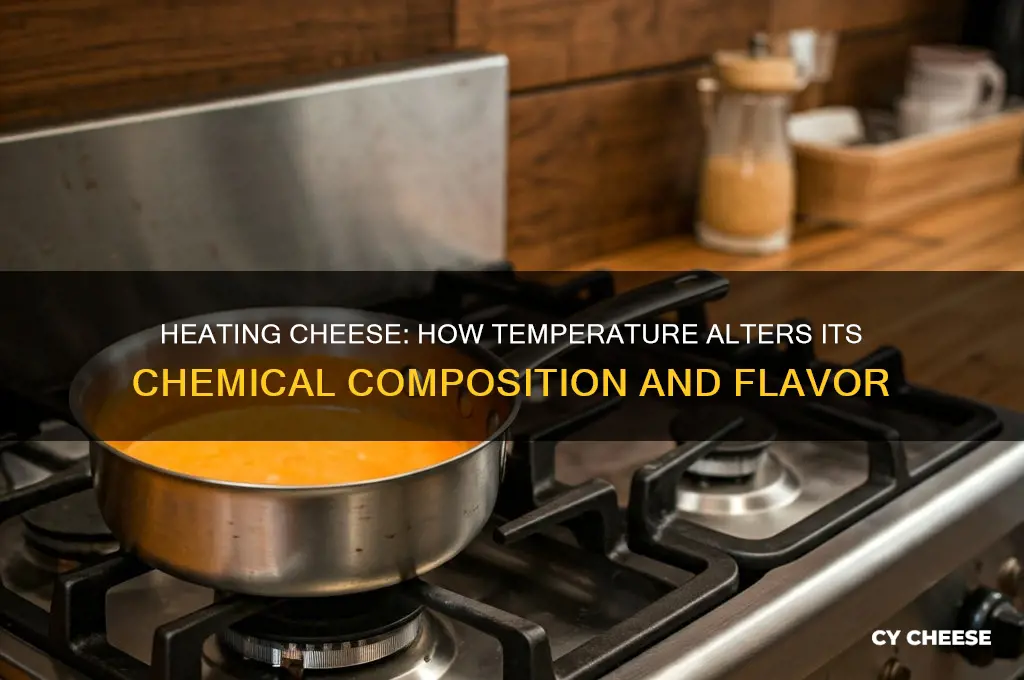

When cheese is heated, its chemical composition undergoes noticeable changes due to the thermal breakdown of proteins, fats, and moisture. Proteins denature and coagulate, altering texture and potentially releasing volatile compounds that affect flavor. Fats can melt and separate, leading to oiling-off, while moisture evaporates, concentrating solids and intensifying taste. Additionally, heat-induced reactions like Maillard browning can create new flavor compounds, further transforming the cheese’s profile. These changes vary depending on the cheese type, heating method, and duration, making the process a fascinating interplay of chemistry and culinary science.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Protein Denaturation | Heating cheese causes the proteins to denature, changing their structure and potentially leading to a firmer texture. |

| Fat Separation | High heat can cause fats to separate from the cheese matrix, resulting in oiling off or a greasy appearance. |

| Moisture Loss | Heat drives off moisture, concentrating the cheese's flavor and potentially making it drier. |

| Melting Behavior | Different cheeses melt differently due to variations in protein and fat content. Heating alters the melting point and flow properties. |

| Flavor Development | Heating can intensify flavors through Maillard reactions (browning) and the breakdown of certain compounds, creating new flavor molecules. |

| Texture Changes | Texture can become softer and more gooey when melted, or firmer and chewier if heated beyond the melting point. |

| Nutrient Loss | Some heat-sensitive nutrients, like certain vitamins, may degrade with prolonged heating. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Protein Denaturation: Heat alters cheese proteins, changing texture and meltability

- Fat Separation: Heat causes oil to separate from solids in cheese

- Moisture Loss: Heating evaporates moisture, making cheese drier and firmer

- Flavor Changes: Heat intensifies or alters cheese flavors due to chemical reactions

- Starch Gelatinization: Heat affects starch in cheese, impacting its structure

Protein Denaturation: Heat alters cheese proteins, changing texture and meltability

Heat transforms cheese, and at the heart of this transformation lies protein denaturation. When cheese is heated, the proteins—primarily casein—begin to unravel and lose their structured shape. This process is not merely a culinary curiosity; it’s a fundamental chemical change that dictates how cheese melts, stretches, and interacts with other ingredients. For example, mozzarella’s signature stretchiness is a direct result of heat-induced protein denaturation, where the casein molecules align and form a cohesive network. Understanding this mechanism allows cooks to predict how different cheeses will behave under heat, from the smooth melt of cheddar to the resistant crumbly texture of feta.

To observe protein denaturation in action, consider a simple experiment: heat a slice of cheddar cheese gradually. At around 130°F (54°C), the proteins begin to denature, causing the cheese to soften. By 150°F (65°C), the melt becomes more fluid as the proteins fully unravel and release moisture. However, overheating—beyond 175°F (79°C)—can lead to a grainy texture as the proteins coagulate excessively. This demonstrates the delicate balance between heat application and desired texture, a principle critical in both home cooking and industrial cheese processing.

From a practical standpoint, controlling temperature is key to harnessing protein denaturation for optimal results. For grilled cheese sandwiches, maintain a medium-low heat (275–300°F or 135–150°C) to allow gradual melting without burning the bread. When making sauces, such as fondue or mornay, keep the heat below 160°F (71°C) to prevent protein clumping. Additionally, pairing cheeses with specific heat applications—like using high-moisture mozzarella for pizzas or semi-hard gruyère for gratins—maximizes their meltability and texture. These techniques ensure that protein denaturation works in your favor, not against it.

Comparatively, not all cheeses respond to heat in the same way due to differences in protein structure and moisture content. Fresh cheeses like ricotta or goat cheese have less structured proteins and higher water content, making them prone to separation when heated. In contrast, aged cheeses like Parmesan contain more stable proteins and less moisture, allowing them to brown and crisp without fully melting. This highlights the importance of selecting the right cheese for the desired outcome, whether it’s a creamy sauce or a crispy topping.

In conclusion, protein denaturation is the silent architect behind cheese’s behavior when heated. By understanding how heat alters protein structure, cooks can manipulate texture, meltability, and flavor with precision. Whether crafting a perfect melt or avoiding a culinary mishap, this knowledge transforms cheese from a simple ingredient into a versatile tool in the kitchen. Master this principle, and you’ll elevate every dish that calls for cheese under heat.

Cheese Talk: Did Your Piercer Discuss Aftercare with You?

You may want to see also

Fat Separation: Heat causes oil to separate from solids in cheese

Heat transforms cheese, and one of the most noticeable changes is fat separation. As cheese warms, its oily component, primarily composed of milk fats, begins to melt and pool away from the solid protein matrix. This phenomenon is particularly evident in cheeses with higher fat content, such as cheddar or mozzarella, where the oil becomes visibly distinct from the chewy, stringy texture that remains. For instance, when heating a slice of cheddar on a sandwich, you might observe a shiny, golden layer of oil forming around the edges, a clear sign of fat separation.

Understanding this process is crucial for culinary applications. To minimize fat separation, consider heating cheese at lower temperatures (around 120°C to 150°C) and for shorter durations. For example, when making a grilled cheese sandwich, use medium heat and cook for 3–4 minutes per side, allowing the cheese to melt evenly without excessive oil release. Alternatively, choose cheeses with lower fat content, like fresh mozzarella or part-skim ricotta, which are less prone to separation when heated.

From a scientific perspective, fat separation occurs because the protein network in cheese weakens under heat, releasing trapped fat globules. This process is accelerated in aged cheeses, where the protein structure is more fragile. For instance, aged cheddar separates more readily than its younger counterpart. To counteract this, chefs often pair high-fat cheeses with ingredients that absorb excess oil, such as bread or starchy vegetables, ensuring a balanced texture in dishes like cheese fondue or baked pasta.

Practical tips can help manage fat separation in home cooking. When melting cheese for sauces, add a small amount of starch (e.g., 1 teaspoon of cornstarch per cup of cheese) to stabilize the emulsion and reduce oil separation. For grilled dishes, blot excess oil with a paper towel before serving. Additionally, storing cheese at room temperature for 15–20 minutes before heating can promote more even melting, reducing the likelihood of fat pooling. By mastering these techniques, you can harness the effects of heat on cheese to enhance both flavor and presentation.

Crunchy Breadsticks: A Perfect Pairing for Fruit and Cheese Platters?

You may want to see also

Moisture Loss: Heating evaporates moisture, making cheese drier and firmer

Heating cheese transforms its texture, primarily due to moisture loss. As temperature rises, water molecules gain energy and escape as vapor, leaving behind a denser, firmer structure. This process is most noticeable in cheeses with higher moisture content, such as mozzarella or fresh chèvre. For example, melting mozzarella on a pizza at 450°F (230°C) reduces its moisture content by up to 15%, creating a stretchy yet drier texture. Understanding this mechanism allows cooks to predict how cheese will behave under heat, whether crisping up in a grilled cheese or browning in a baked dish.

To mitigate excessive dryness, control both temperature and duration. Low and slow heating (e.g., 300°F/150°C for 10–15 minutes) preserves more moisture than high-heat methods. Adding a moisture barrier, like brushing cheese with butter or oil, can also slow evaporation. For instance, sprinkling grated Parmesan on a casserole and covering it with foil until the final 5 minutes of baking ensures even melting without over-drying. These techniques are particularly useful for aged, low-moisture cheeses like Parmesan, which are prone to becoming gritty when overheated.

The degree of moisture loss directly impacts flavor concentration. As water evaporates, fat and protein content become more pronounced, intensifying savory notes. However, this can backfire if the cheese becomes too dry, leading to a chalky or rubbery mouthfeel. For optimal results, pair high-moisture cheeses (like Brie) with gentle heat and serve immediately, while using drier cheeses (like cheddar) for longer cooking times. Experimenting with combinations—such as layering fresh mozzarella with tomato sauce for moisture retention—can balance texture and taste in heated dishes.

Practical applications extend beyond cooking. For instance, reheating leftover macaroni and cheese often results in a drier, less creamy texture due to moisture loss. To counteract this, add a splash of milk or cream and reheat at a low temperature (250°F/120°C), stirring occasionally. Similarly, when making cheese crisps, thinly slice semi-hard cheeses like Gruyère and bake at 350°F (175°C) for 6–8 minutes, watching closely to prevent excessive drying. These adjustments ensure the cheese retains its desired consistency while enhancing flavor through controlled moisture reduction.

Scraping Mold from Fermented Cheese: Safe Practice or Risky Move?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Flavor Changes: Heat intensifies or alters cheese flavors due to chemical reactions

Heat transforms cheese, and not just in texture. The chemical reactions unleashed by elevated temperatures act as a flavor amplifier, intensifying existing notes and sometimes creating entirely new ones. This phenomenon is rooted in the Maillard reaction, a complex process where amino acids and reducing sugars interact, producing hundreds of flavor compounds. Think of the deep, nutty aroma of browned cheddar on a grilled cheese sandwich – that's the Maillard reaction at work.

At lower temperatures, around 120-150°F (49-65°C), cheeses like mozzarella and provolone melt smoothly, their mild flavors becoming richer and slightly sweeter. This is due to the breakdown of lactose, the natural sugar in milk, into simpler sugars that our taste buds perceive as sweeter. As temperatures climb above 160°F (71°C), the Maillard reaction kicks into high gear, particularly in cheeses with higher protein content like cheddar and Gruyère. This results in the development of complex, savory flavors often described as "caramelized," "toasty," or even "meaty."

However, heat's impact isn't always desirable. Overheating can lead to a loss of subtlety, with delicate flavors becoming overwhelmed by bitterness or a burnt taste. This is especially true for softer cheeses like Brie or Camembert, which can become unpleasantly pungent when exposed to high heat for too long. The key lies in understanding the cheese's melting point and desired flavor profile. For example, a gentle melt at 130°F (54°C) will enhance the creamy texture and mild sweetness of fresh mozzarella, while a hotter temperature of 170°F (77°C) is needed to unlock the full, nutty potential of aged Gouda.

Experimentation is key to mastering the art of heated cheese. Start with small batches, monitoring temperature closely with a kitchen thermometer. Observe how different cheeses respond to heat, noting changes in aroma, texture, and taste. Remember, the goal isn't to mask the cheese's inherent character but to coax out its hidden depths, creating a symphony of flavors that sing in perfect harmony.

Should You Remove the Paper Wrapping from Brie Cheese?

You may want to see also

Starch Gelatinization: Heat affects starch in cheese, impacting its structure

Heat transforms the starch in cheese, a process known as gelatinization, which significantly alters its texture and mouthfeel. This phenomenon is particularly relevant in cheeses that contain added starch, such as processed cheese slices or certain types of fresh cheeses. When heated, the starch granules absorb water and swell, disrupting their crystalline structure. This results in a gel-like consistency, contributing to the smooth, creamy texture often desired in melted cheese applications.

For instance, consider the classic grilled cheese sandwich. As the cheese melts, the starch gelatinization process occurs, creating a cohesive, stretchy interior that contrasts with the crispy exterior. This transformation is crucial for achieving the desired sensory experience.

The degree of starch gelatinization depends on several factors, including the type of starch, its concentration, and the temperature and duration of heating. Different starches have varying gelatinization temperatures, typically ranging from 55°C to 75°C (131°F to 167°F). For example, potato starch gelatinizes at a lower temperature compared to cornstarch. In cheese, the optimal heating conditions for starch gelatinization must be carefully controlled to avoid overcooking or undercooking, which can lead to a grainy or rubbery texture.

To harness the benefits of starch gelatinization in cheese, consider the following practical tips. When making a cheese sauce, gradually add the cheese to the heated liquid while stirring constantly. This ensures even heat distribution and prevents the starch from clumping. For baked dishes like lasagna or casseroles, allow the dish to rest for 5-10 minutes after removing it from the oven. This resting period enables the gelatinized starch to set, resulting in a more stable and sliceable texture.

In the context of cheese aging, starch gelatinization can also play a role. As cheese matures, its moisture content decreases, and the starch may undergo partial gelatinization due to the increased concentration of solids. This can contribute to the development of a firmer texture and more complex flavor profile in aged cheeses. However, excessive heat exposure during aging or storage can accelerate starch gelatinization, potentially leading to undesirable textural changes. Therefore, maintaining proper temperature and humidity control is essential for preserving the desired characteristics of aged cheeses.

Understanding Cheese Measurements: Ounces in a Pound of Cheese

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, heating cheese causes chemical changes, including protein denaturation, fat separation, and moisture evaporation, altering its texture and flavor.

Heating cheese denatures its proteins, causing them to lose their structure and coagulate, which results in a firmer or melted texture depending on the type of cheese.

Heating does not change the fat content of cheese, but it can cause fats to separate from other components, leading to oiling or greasiness on the surface.