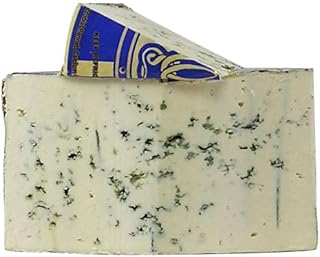

Blue cheese is a category of cheese with a distinctive appearance, taste, and aroma. The unique characteristics of blue cheese are due to the diverse microbiota that develop during its manufacturing and ripening stages. The process of making blue cheese involves six standard steps, with additional ingredients and processes to create its particular properties. The first step is to pasteurise milk, which can come from cows, sheep, buffalo, or goats. A starter culture is then added to the milk, which contains bacteria and enzymes that convert lactose into lactic acid. This step lowers the pH of the milk and prepares it for the next stage. A mould culture, typically Penicillium roqueforti, is then introduced to the milk to create the blue veins. This mould is added as a freeze-dried inoculum, and its growth is facilitated by piercing the cheese and ripening it at low temperatures. The cheese is then coagulated with rennet, an enzyme, and the curds are formed and cut before being pressed and shaped. Finally, the cheese is aged for several weeks to several months, during which time the mould continues to grow and produce enzymes that contribute to the flavour and texture of the blue cheese.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Microbes used | Penicillium roqueforti, Lactococcus lactis, Enterococcus faecalis, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus curvatus, Leuconostoc mesenteroides, Staphylococcus equorum, Staphylococcus sp., Geotrichum candidum, Brevibacterium linens, Streptococcus thermophiles, Lactobacillus helveticus, Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp., Debaryomyces hansenii, Kluyveromyces marxianus, Yarrowia lipolytica, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Candida spp., Pichia spp., Corynebacteria |

| Role of microbes | Induce fermentation, acidification, and flavour development; contribute to texture, aroma, and visual appearance |

| Microbe addition step | Before or after curds form |

| Cheese piercing | Facilitates air entry and uniform development of P. roqueforti |

| Curing methods | Used to characterize microbial populations |

| Milk type | Cow, sheep, buffalo, goat, or a mixture |

| Pasteurization | Optional; some blue cheeses like Roquefort are not pasteurized |

| Salt | Used for curing and preservation; amount should not exceed 200 parts per million of milk and milk products |

| Sugar | Added to autoclaved, homogenized milk |

| Temperature | Blue cheese is aged in temperature-controlled environments; ripening temperature of 8–12 °C |

| Humidity | High relative humidity of >90% during ripening |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Microbes are added to milk to induce fermentation

The main bacteria used in this process are lactic acid bacteria (LAB), which can be naturally occurring in milk or added as industrial starter cultures. Examples of LAB commonly used in cheese-making include Lactococcus lactis, Streptococcus salivarius, and Lactobacillus helveticus. These bacteria not only contribute to acid production but also play a role in curd formation, converting liquid milk into a gel-like substance.

In the case of blue cheese, the starter culture typically includes Penicillium roqueforti, a type of mould that gives the cheese its characteristic blue veins. This mould is often added as a freeze-dried culture, and its growth is influenced by factors such as temperature, humidity, and oxygen levels. The piercing of the cheese during production also facilitates the entry of air, promoting the development of P. roqueforti and contributing to the desired visual appearance.

The addition of microbes to induce fermentation is a delicate process, as the specific combinations and conditions influence the final product. Different strains of bacteria and fungi work together to create the unique sensory characteristics of blue cheese, including its flavour, aroma, and texture. The complex microbial interactions in blue cheese contribute to its distinctiveness and complexity, making it a favourite among cheese connoisseurs.

Furthermore, the use of microbes in blue cheese production extends beyond fermentation. The maturation and ripening stages also involve microbial activity, with the continued growth of mould and the presence of other microorganisms, such as yeasts and bacteria, contributing to the final flavour, texture, and aroma profiles. The diversity and interplay of these microbes give rise to the myriad characteristics that define blue cheese varieties worldwide.

Cheese Making: Skim or Whole Milk?

You may want to see also

Microbes are used to create blue veins in cheese

Microbes play a crucial role in creating the distinctive blue veins in cheese, specifically in blue cheeses such as Roquefort, Gorgonzola, and Stilton. The process involves the use of specific bacteria and mould cultures, which contribute to both the appearance and flavour of the cheese.

The first step in creating blue cheese involves inoculating milk with a starter culture, which contains bacteria such as Lactococcus lactis and Lactobacillus plantarum. These bacteria initiate the fermentation process by converting lactose into lactic acid, reducing the pH of the milk. This step is essential for creating the optimal environment for the mould culture to thrive and develop the blue veins.

The mould culture primarily responsible for the blue veins in cheese is Penicillium roqueforti, a common blue mould. This mould is added to the milk after the starter culture, creating the characteristic blue-veined appearance. Penicillium roqueforti also contributes significantly to the flavour of blue cheese by producing enzymes and breaking down fat during the ripening process, resulting in the formation of free fatty acids that give blue cheese its unique piquant flavour.

In addition to Penicillium roqueforti, other microbes can also be found in blue cheese, such as Lactococcus lactis, Enterococcus faecalis, and Lactobacillus curvatus. These microbes contribute to the aromatic profile of the cheese by producing volatile compounds. The diversity of microbial communities in blue cheese, including bacteria and fungi, influences the overall quality, sensory characteristics, and final appearance of the product.

The process of creating blue veins in cheese involves piercing the cheese to facilitate the entry of air and promote the growth of Penicillium roqueforti throughout the cheese matrix. This technique ensures the uniform development of the mould, resulting in the distinct blue veins that characterise blue cheese.

Overall, the creation of blue veins in cheese is a complex process that relies on the careful selection and cultivation of specific microbes, particularly bacteria and mould cultures. The interaction between these microbes and the cheese matrix results in the formation of unique sensory characteristics, making blue cheese a distinctive and versatile delicacy.

Making Cheese with Vinegar: A Simple Guide

You may want to see also

Microbes are added to milk to lower its pH

The process of making blue cheese involves several steps, with the addition of microbes being a key stage. The milk used can be from cows, sheep, buffalo, or goats, and it typically undergoes pasteurisation. However, some varieties, like Roquefort, are not pasteurised.

After pasteurisation, a starter culture is added to the milk. This culture contains microbes (bacteria) that induce fermentation, specifically the conversion of lactose to lactic acid, thereby acidifying the milk. This process lowers the pH of the milk and prepares it for the next steps in cheesemaking. Examples of microbes used as starter cultures include Lactococci, Streptococci, and Lactobacilli. Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis and Lactococcus lactis ssp. cremoris, for instance, are common lactic acid bacteria used in cheesemaking.

The addition of microbes is crucial for developing the distinctive characteristics of blue cheese, including its flavour, texture, and aroma. The specific microbes used, as well as their interactions with other ingredients and environmental factors, contribute to the unique qualities of each type of blue cheese.

During the cheesemaking process, the milk is warmed to the optimal growth temperature of the microbes in the starter culture, enhancing the rate of fermentation. This warming process increases the production of acid, which helps form curds and contributes to the removal of water from the milk proteins.

In addition to the starter cultures, mould cultures are also added to the milk to create the characteristic blue veins in blue cheese. Penicillium roqueforti is the most common mould culture used, and it can be added before or after the curds form. This mould grows during the ageing process, producing enzymes that further influence the flavour and texture of the cheese.

Cheese Cellar Storage: An Old-Fashioned Practice?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Microbes are used to pierce the cheese to allow the development of P. roqueforti

Blue cheese is characterised by the growth of P. roqueforti, a blue-veined appearance, soft texture, lower acidity or high pH, and a flavour dominated by methyl ketones. The mould culture, P. roqueforti, is added to the milk to create the blue veins. The cheese is then pierced to allow oxygen to reach the microbes, which stimulates their growth and contributes to the typical visual appearance of blue cheese when cut.

Piercing the cheese is an important practice in blue-veined cheeses. The microflora of the whole cheese or particular sections are affected by piercing. The piercing allows oxygen to reach the microbes, which stimulates their growth and contributes to the typical blue cheese appearance when cut. The microbial flora of blue cheese is complex, particularly when raw milk is used. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and fungi dominate the process.

The process of making blue cheese consists of six standard steps, but additional ingredients and processes are required to give it its particular properties. The first phase of production involves preparing a Penicillium roqueforti inoculum before actual cheese production. Multiple methods can be used to achieve this, but all involve the use of a freeze-dried Penicillium roqueforti culture. Although Penicillium roqueforti can be found naturally, cheese producers today use commercially manufactured P. roqueforti.

In the second phase, a starter culture is added to the milk. This culture contains bacteria and enzymes that help convert the lactose in the milk into lactic acid. The addition of the starter culture helps lower the pH of the milk and prepares it for the next step in the cheese-making process. Once the starter culture has been added, a mould culture is introduced to the milk. The most common mould culture is Penicillium roqueforti, which creates the blue veins in blue cheese.

After the curds are formed and cut, the whey is drained, and the cheese is pressed and shaped into the desired form. The cheese is then aged for several weeks to several months. During this time, the mould continues to grow and produce enzymes that contribute to the flavour and texture of the cheese.

Spain's Cheese Culture: A Tasty Overview

You may want to see also

Microbes are added to milk to convert lactose to lactic acid

Microbes, or bacteria, are added to milk to kickstart the fermentation process and convert lactose to lactic acid. This process is known as acidification and is essential to transforming milk into cheese.

The microbes used in this process are commonly referred to as "starter cultures". Examples include Lactococci, Streptococci, and Lactobacilli. Lactococci, for instance, are common lactic acid bacteria used to make cheeses like cheddar. Streptococci are used in cheeses like mozzarella, and Lactobacilli are used in Swiss and alpine cheeses.

In blue cheese production, milk is typically pasteurized before the addition of starter cultures. However, some blue cheeses, like Roquefort, are made with unpasteurized milk. The starter culture is then added to the milk, lowering the pH and preparing it for the next steps in cheesemaking.

After the starter culture is added, a mould culture is introduced to the milk. The most common mould culture used in blue cheese is Penicillium Roqueforti, which creates the distinctive blue veins in the cheese. This mould can be found naturally, but today, cheese producers primarily use commercially manufactured Penicillium Roqueforti.

The addition of microbes to milk to convert lactose to lactic acid is a crucial step in cheesemaking, and the specific microbes used can vary depending on the type of cheese being produced.

Goat Cheese at Cicis: What's the Deal?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The most common mould culture used to make blue cheese is Penicillium roqueforti, which creates the blue veins. Other microbes used include Lactococcus lactis, Enterococcus faecalis, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus curvatus, Leuconostoc mesenteroides, Staphylococcus equorum, and Staphylococcus sp.

The microbes used to make blue cheese contribute to its flavour, texture and aroma. The characteristic odour impressions of blue cheese originate from the methyl ketones, which give fruity, floral, and spicy notes. The overall quality of blue cheese is thought to result from the combined action of all members of the microbiota.

The microbial flora of blue cheese, including mesophilic lactic acid bacteria (Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis, L. lactis subsp. cremoris and sometimes cit+ lactococci and leuconostocs), produce an open-textured curd through the production of CO2 from citrate.

Piercing the cheese facilitates the entry of air, allowing uniform development of P. roqueforti into the cheese matrix, which contributes to the typical visual aspect at cutting.