Cheese is a food that contains a high number of living, metabolising microbes. The variety of cheeses produced reflects the versatility of the microorganisms used in cheese-making. The magic of cheese only needs four ingredients: milk, salt, rennet (or another coagulant), and microbes. However, there is a wide range of microbes that give us the variety of cheeses we enjoy. The process of making cheese involves transforming milk into solid curds and liquid whey through the coagulation of the milk protein casein. The coagulation of casein is usually accomplished through two complementary methods: acidification and proteolysis. The milk sugar lactose is broken down into lactic acid by a group of bacteria referred to as lactic acid bacteria (LAB). These bacteria convert the lactose (milk sugar) to lactic acid and lower the milk's pH. As cheese ripens, bacteria break down the proteins, altering the flavour and texture of the final cheese. The proteins first break into medium-sized pieces (peptides) and then into smaller pieces (amino acids). During ripening, some cheeses are inoculated with a fungus such as Penicillium. The rind of the cheese is formed when the surface of the cheese is colonized by bacteria and fungi.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Microbes used in cheese-making | Bacteria, yeast, and filamentous fungi (molds) |

| Types of bacteria | Lactic acid bacteria (LAB), mesophilic bacteria, thermophilic bacteria, streptococci, Brevibacterium linens (B. linens), corynebacteria |

| Role of bacteria | Convert milk sugar lactose into lactic acid, break down proteins into odor compounds, contribute to flavor and texture, control the growth of undesirable bacteria |

| Types of yeast | Geotrichum candidum, Saccharomyces cerevisiae |

| Role of yeast | Produce vitamins and other compounds, contribute to color and aroma, exhibit mold-like tendencies |

| Types of mold | Blue molds (Roqueforti, P. glaucum), white molds (P. camembertii) |

| Role of mold | Give unique flavor and texture, grow in low-oxygen environments, produce digestive enzymes |

| Other microbes | Marine microbes (Halomonas) |

| Cheese characteristics influenced by microbes | Flavor, smell, texture, color, aroma |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Microbes break down milk proteins and sugars, forming curds

- Microbes are responsible for the unique flavours, smells and textures of cheese

- Microbes are used to prevent spoilage and preserve the milk

- Microbes are added to milk to start the cheesemaking process

- Microbes are used to create the rind of the cheese

Microbes break down milk proteins and sugars, forming curds

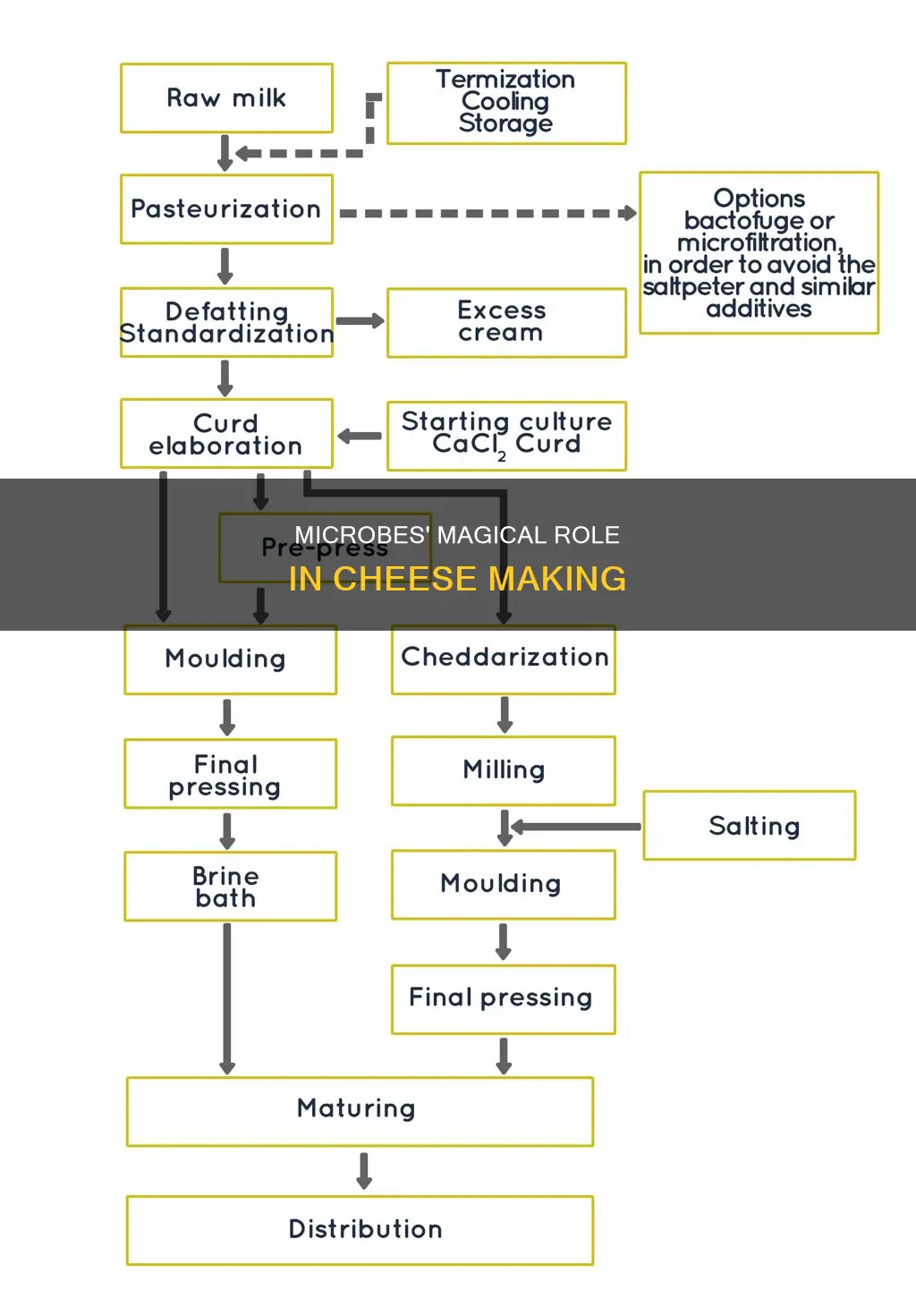

The process of making cheese involves transforming milk into solid curds and liquid whey through the coagulation of milk proteins, specifically casein. This coagulation is achieved through two methods: acidification and proteolysis.

Microbes play a crucial role in the acidification process, where they break down milk proteins and sugars, forming curds. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB), also known as "starter cultures", are responsible for converting the milk sugar lactose into lactic acid. This fermentation process lowers the pH of the milk, creating an environment inhospitable to spoilage organisms. The milk is warmed to the optimal growth temperature for the microbes in the starter culture, increasing the rate of fermentation and curd formation.

The specific bacteria used in this process depend on the desired cheese variety. Mesophilic bacteria, which thrive at room temperature but die at higher temperatures, are used to make mellow cheeses such as Cheddar, Gouda, and Colby. On the other hand, thermophilic bacteria, which thrive at higher temperatures of around 55°C, are used for sharper cheeses like Gruyère, Parmesan, and Romano.

The breakdown of milk proteins by microbes is a key step in developing the flavour and texture of the final cheese. As proteins break down into peptides and then into amino acids, they can further transform into highly flavoured molecules called amines, contributing to the complex flavours of cheese.

Additionally, microbes can cooperate to enhance the cheese-making process. For example, Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeasts consume the lactic acid produced by LAB and, in return, produce vitamins and compounds beneficial to the LAB. The presence of thread-like fungal filaments can also act as pathways for surface bacteria to travel deeper into the cheese.

The diversity of microbes involved in cheese-making, including bacteria, yeast, and mould, contributes to the wide range of flavours, smells, and textures found in different cheeses.

Yogurt Lasagna: A Healthy Alternative to Cheese?

You may want to see also

Microbes are responsible for the unique flavours, smells and textures of cheese

The unique flavours, smells and textures of cheese are a result of the microbial activity that occurs during the cheese-making process. Cheese is a traditional food incorporated into many cuisines and is consumed directly or used as an ingredient in cooking. It is one of the few foods that contain extraordinarily high numbers of living, metabolising microbes.

The broad groups of cheese-making microbes include many varieties of bacteria, yeast, and filamentous fungi (molds). In cheese-making, milk proteins and sugars change. The milk sugar lactose is broken down into lactic acid by fermentation that depends on a group of bacteria called lactic acid bacteria (LAB). Traditional cheese-makers relied on naturally occurring LAB in milk, but today, it is common to inoculate milk with industrial starter cultures, defined groups of bacteria specifically chosen for cheese-making. To increase the rate of fermentation, the milk is warmed to the optimal growth temperature of microbes in the starter culture. The acid produced during fermentation helps form curds and contributes to the removal of water held within the milk proteins.

The variety of microbes used in the cheese-making process results in the variety of cheeses produced. For example, the orange-pigmented bacterium Brevibacterium linens is responsible for the distinctive colour and aroma of washed-rind cheeses. Some cheeses, like great alpine cheeses, are wiped only during part of their ripening, producing a muted complexity of flavour, rather than the strong smell that accompanies many cheeses that host B. linens.

The ageing stage of cheesemaking is when cheese is truly transformed into mature cheese with its unique flavours, aromas, and textures. During ageing, starter cultures and non-starter lactic acid bacteria continue to grow and metabolise the interior of the cheese, while the surface of the cheese is colonised by bacteria and fungi that form a multispecies biofilm, termed the 'rind' of the cheese. For example, the surfaces of bloomy rind cheeses are colonised by the filamentous fungus Penicillium camemberti, whereas Penicillium roqueforti grows inside crevices of blue cheeses.

The contribution of microbes to the unique characteristics of cheese has been well-characterised, and pure cultures of these microbes are commonly used by cheesemakers. However, modern microbiology has yet to fully explain the role of all microbes in cheese flavour and ripening.

Mac and Cheese: Egg or No Egg?

You may want to see also

Microbes are used to prevent spoilage and preserve the milk

Microbes play a crucial role in preventing spoilage and preserving milk during the cheese-making process. This process likely dates back to Neolithic times, when it served as a means of preserving milk.

Cheese is a traditional food incorporated into various cuisines and contains a high number of living, metabolizing microbes. The broad groups of cheese-making microbes include bacteria, yeast, and filamentous fungi (molds). These microbes contribute to the distinct characteristics of cheese, including flavour, smell, and texture.

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are commonly used as "starter cultures" in cheese-making. They play a vital role in converting milk sugar (lactose) into lactic acid, lowering the cheese's pH, and inhibiting the growth of spoilage organisms. This process, known as acidification, helps separate the curds and whey and control the growth of undesirable bacteria. The milk is warmed to the optimal growth temperature of the microbes in the starter culture to increase the rate of fermentation.

During the aging process, the starter cultures and non-starter lactic acid bacteria continue to grow and metabolize the interior of the cheese. The surface of the cheese is simultaneously colonized by bacteria and fungi, forming a biofilm called the "rind." This rind contributes to the preservation of the cheese by inhibiting spoilage organisms.

Additionally, specific microbes, such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeasts, play a cooperative role in the cheese ecosystem. They consume the lactic acid produced by LABs and, in return, manufacture vitamins and other compounds that the LABs require for their growth. This symbiotic relationship between microbes helps maintain a stable environment that prevents spoilage and promotes the preservation of milk into cheese.

Cheese Blocks: Make the Most of Every Slice

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Microbes are added to milk to start the cheesemaking process

Microbes are essential to the cheesemaking process. They are added to milk to start the process and are responsible for the transformation of milk into cheese. The broad groups of cheese-making microbes include bacteria, yeast, and filamentous fungi (molds).

In cheesemaking, milk proteins and sugars change. The milk sugar lactose is broken down into lactic acid by a group of bacteria called lactic acid bacteria (LAB). These bacteria are often referred to as "starter cultures" as they play a crucial role in converting lactose into lactic acid, lowering the cheese's pH, and inhibiting the growth of spoilage organisms. There are two main types of lactic acid bacteria: lactococci (spherical) and lactobacilli (rod-shaped).

The process of cheesemaking involves adding "starter" bacteria to milk. These bacteria can be of two types: mesophilic and thermophilic. Mesophilic bacteria thrive at room temperature and are used for making mellow cheeses like Cheddar, Gouda, and Colby. On the other hand, thermophilic bacteria prefer higher temperatures (around 55°C) and are used for sharper cheeses such as Gruyère, Parmesan, and Romano.

The addition of microbes to milk is a delicate process that requires specific conditions for optimal growth. The milk is warmed to the ideal temperature for the microbes in the starter culture, facilitating their growth and acid production. This acid formation is crucial for the creation of curds and the removal of water from milk proteins.

Furthermore, the diversity in cheese's flavor, smell, and texture can be attributed to the metabolic activities of microbes. Different groups of microbes preferentially grow due to variations in milk sources, pH levels, salt content, moisture, and temperature during cheesemaking and aging. Additionally, the interaction between microbes, such as the cooperation between Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeasts and LABs, further contributes to the unique characteristics of cheese.

Explore the Versatile Uses of Monterey Jack Cheese

You may want to see also

Microbes are used to create the rind of the cheese

Microbes are essential to the process of making cheese, and they are responsible for the variety of cheeses available today. The use of microbes in cheese-making is not a new phenomenon, with evidence suggesting that people have been making cheese with microbes since the late Stone Age.

Cheese is a fermented milk product, and one of the few foods that contains extraordinarily high numbers of living, metabolizing microbes. The milk sugar lactose is broken down into lactic acid by a group of bacteria called lactic acid bacteria (LAB). These bacteria are often referred to as "starter cultures" as they play a crucial role in converting lactose into lactic acid, lowering the cheese's pH, and making the cheese inhospitable to spoilage organisms.

During the aging process, the surface of the cheese is colonized by bacteria and fungi that form a multispecies biofilm called the 'rind' of the cheese. This rind is a result of the careful balance of yeast, mold, and bacteria that give rise to natural rinds. For example, the fungus Penicillium camemberti colonizes the surface of bloomy rind cheeses, while Penicillium roqueforti grows inside the crevices of blue cheeses.

The rind contributes to the unique flavor, smell, and texture of the cheese. For instance, the orange-pigmented bacterium Brevibacterium linens (B. linens) is responsible for the distinctive color and aroma of washed-rind cheeses. B. linens breaks down proteins into odor compounds, producing oniony, garlicky, fishy, and sweaty aromas.

The use of microbes in creating the rind of cheese is a complex and fascinating process that contributes to the overall character and quality of the final product.

Ribeye for Philly Cheese Steak: A Perfect Match?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Microbes are microorganisms such as bacteria, yeast, and fungi (molds) that are used in cheese-making. Cheese is a fermented milk product that requires microbes to transform milk into cheese and develop its flavor, smell, and texture.

The milk sugar lactose is broken down into lactic acid by a group of bacteria called lactic acid bacteria (LAB). This process of fermentation lowers the pH of the milk, creating an environment inhospitable to spoilage organisms. The acid also helps form curds, contributing to the separation of curds and whey.

Some common microbes used in cheese-making include Brevibacterium linens, which is responsible for the distinctive smell of many surface-ripened cheeses, and Geotrichum candidum, a yeast that gives some cheeses a "brainy" appearance. Blue molds like Penicillium roqueforti and P. glaucum are used in blue cheeses, contributing to their unique flavor and texture.

During the aging process, microbes break down milk proteins into smaller pieces, creating highly flavored molecules called amines. Different combinations of microbes interact with each other and the environment, resulting in the diverse flavors, aromas, and textures found in mature cheeses.

Traditional cheese-makers relied on naturally occurring microbes in milk, but modern cheese-making often uses controlled inoculation with specific starter cultures of microbes. However, traditional methods like "backslopping," where a portion of whey from a previous batch is used in the next batch, are still practiced and can result in the long-term domestication of certain microbes.