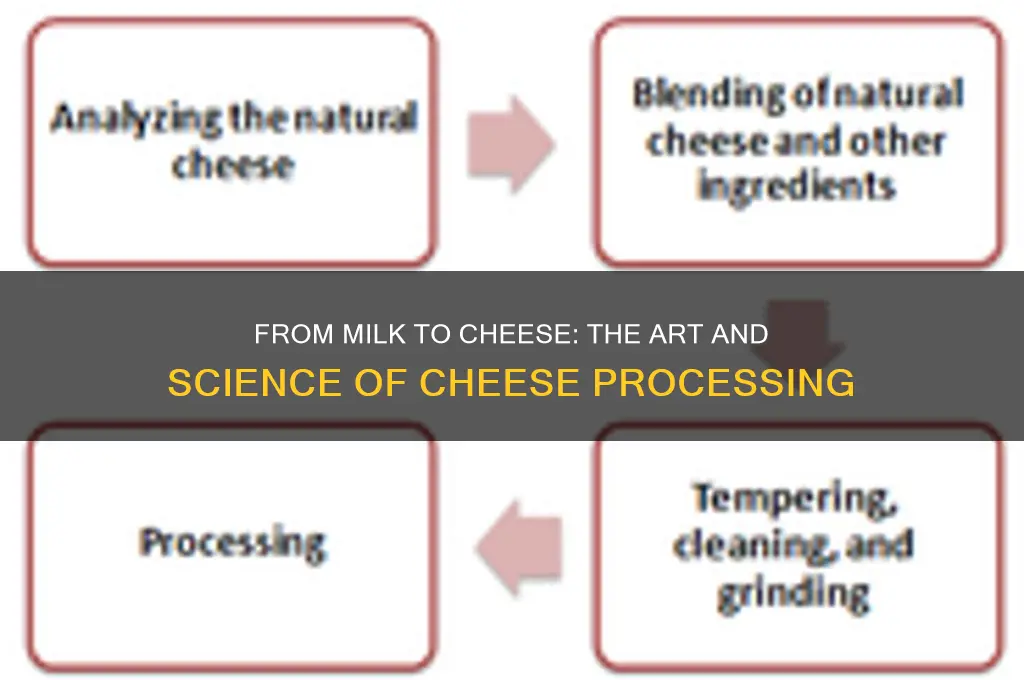

Cheese processing is a fascinating blend of art and science, transforming milk into a diverse array of flavors, textures, and aromas. The journey begins with the selection of milk, often from cows, goats, or sheep, which is then pasteurized or used raw, depending on the desired outcome. The next critical step is the addition of bacterial cultures and rennet, which coagulate the milk, separating it into curds and whey. The curds are then cut, stirred, and heated to release moisture and develop the desired texture. After draining and pressing, the cheese is often salted, either by brining or dry salting, to enhance flavor and preserve it. Finally, the cheese is aged or ripened under controlled conditions, allowing enzymes and bacteria to further develop its unique characteristics. This meticulous process, varying widely across different cheese types, ensures the creation of the rich, complex flavors and textures that cheese lovers cherish.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Milk Selection & Preparation: Choosing milk type, pasteurization, and adding starter cultures to initiate fermentation

- Coagulation Process: Adding rennet or acids to curdle milk, separating curds from whey

- Curd Handling: Cutting, stirring, and heating curds to release moisture and develop texture

- Pressing & Molding: Shaping cheese by pressing curds into molds to remove excess whey

- Aging & Ripening: Controlled storage to develop flavor, texture, and rind through microbial activity

Milk Selection & Preparation: Choosing milk type, pasteurization, and adding starter cultures to initiate fermentation

The foundation of any cheese lies in the milk, and the choices made at this stage profoundly influence the final product. Selecting the right milk type is the first critical decision. Cow’s milk is the most common, prized for its balance of fat and protein, but goat and sheep milk offer distinct flavors and textures, often preferred in artisanal cheeses. Buffalo milk, with its high butterfat content, is essential for classics like mozzarella di bufala. Each milk type carries unique microbial flora, which can either be harnessed or controlled during processing, shaping the cheese’s character. For instance, goat’s milk’s natural acidity can accelerate coagulation, requiring precise timing during fermentation.

Once the milk is chosen, pasteurization becomes a pivotal step, though not always mandatory. Raw milk cheeses boast complex flavors due to their native bacteria, but they require strict handling to avoid pathogens. Pasteurization, typically at 72°C for 15 seconds, eliminates harmful microbes while preserving enough beneficial components for fermentation. However, this step must be executed carefully—overheating can denature proteins, hindering curd formation. For raw milk cheeses, aging regulations (e.g., 60 days in the U.S.) ensure safety by allowing acids and salts to naturally inhibit pathogens.

With the milk prepared, the addition of starter cultures initiates fermentation, the heart of flavor development. These cultures, often lactic acid bacteria like *Lactococcus lactis*, convert lactose into lactic acid, lowering pH and creating an environment for coagulation. The dosage of starter culture is crucial—typically 1-2% of milk volume—and varies by cheese type. For example, cheddar requires mesophilic cultures (active at 20-40°C), while Swiss cheeses use thermophilic cultures (active at 45-55°C). Custom blends of cultures can introduce nuanced flavors, such as the tangy notes in blue cheese or the buttery richness in Brie.

The interplay between milk selection, pasteurization, and starter cultures is a delicate dance. Skipping pasteurization demands meticulous sourcing and handling of raw milk, while pasteurized milk requires careful reintroduction of controlled bacteria. The choice of starter culture not only drives fermentation but also interacts with the milk’s inherent properties, such as fat content and protein structure. For instance, high-fat milk may require additional lipase enzymes to break down fats, enhancing flavor complexity.

In practice, this stage demands precision and foresight. Home cheesemakers should source milk from reputable suppliers, ensuring freshness and quality. Commercial producers often standardize milk by adjusting fat and protein levels for consistency. Regardless of scale, understanding the chemistry of milk preparation and fermentation is key. A misstep here—whether in pasteurization temperature or culture dosage—can derail the entire process, underscoring why this phase is both an art and a science.

Does Chef Boyardee Cheese Ravioli Contain Rice? Unveiling Ingredients

You may want to see also

Coagulation Process: Adding rennet or acids to curdle milk, separating curds from whey

The coagulation process is the transformative moment in cheese making where liquid milk becomes a solid foundation for cheese. This critical step involves adding coagulants like rennet or acids to curdle the milk, effectively separating it into curds (the solid part) and whey (the liquid part). Understanding this process is key to mastering cheese production, as it directly influences texture, flavor, and yield.

Rennet, a complex of enzymes derived from animal sources or produced through microbial fermentation, is the most common coagulant in cheese making. Typically, 1/4 to 1/2 teaspoon of liquid rennet diluted in 1/4 cup of cool, non-chlorinated water is added per gallon of milk. This mixture is gently stirred into the milk, which has been heated to the optimal temperature (usually 86-100°F, depending on the cheese type). The enzymes in rennet act on the milk’s proteins, specifically kappa-casein, causing them to bond and form a gel-like structure. This gel is then cut into smaller pieces to release whey, a step that further defines the cheese’s final texture.

Acids, such as citric acid, vinegar, or lemon juice, offer an alternative coagulation method, particularly for fresh cheeses like ricotta or paneer. For instance, adding 1-2 tablespoons of white vinegar or lemon juice to a gallon of heated milk (around 180°F) will cause it to curdle within minutes. This method is simpler and faster but yields a softer, more delicate curd compared to rennet-coagulated cheeses. Acid coagulation is ideal for beginners or those seeking quick results, though it limits the variety of cheeses that can be produced.

The choice between rennet and acids depends on the desired cheese type and the maker’s goals. Rennet-coagulated cheeses, like cheddar or gouda, have a firmer texture and more complex flavor profile due to the slower, enzyme-driven process. Acid-coagulated cheeses, on the other hand, are milder and more crumbly, making them perfect for dishes where the cheese is a supporting ingredient rather than the star.

Separating curds from whey is the final step in coagulation and requires careful handling. For rennet-coagulated cheeses, the curd is cut into uniform cubes using a long knife or curd cutter, then gently stirred to release whey. This step is repeated until the curds reach the desired firmness. Acid-coagulated curds are typically softer and require less manipulation; they can be scooped directly into a cheesecloth-lined mold to drain. Proper separation ensures that excess whey is removed, concentrating the curds and setting the stage for the next steps in cheese making, such as pressing, salting, and aging.

Mastering the coagulation process empowers cheese makers to experiment with different techniques and ingredients, ultimately crafting cheeses with unique characteristics. Whether using rennet or acids, precision in dosage, temperature, and handling is crucial. With practice, this foundational step becomes second nature, opening the door to endless possibilities in the art of cheese making.

Discover the French Name for a Cheese Board: Fromage Delight

You may want to see also

Curd Handling: Cutting, stirring, and heating curds to release moisture and develop texture

The moment curds form in the cheese-making process, they resemble a delicate, custard-like mass, teetering between liquid and solid. This is where curd handling—cutting, stirring, and heating—becomes critical. These steps are not arbitrary; they dictate the cheese’s final texture, moisture content, and even flavor profile. Cutting the curd into uniform pieces exposes more surface area, allowing whey to drain efficiently. Stirring prevents the curds from matting together, ensuring even moisture release, while controlled heating firms the curds and expels additional whey. Each action is a lever, subtly adjusting the cheese’s destiny.

Consider the art of cutting curds, often done with long, thin knives or wires. For semi-soft cheeses like Cheddar, curds are cut into ½-inch cubes to release whey gradually, preserving moisture for a smoother texture. In contrast, hard cheeses like Parmesan require smaller cuts—think pea-sized—to expel more whey, resulting in a drier, denser product. The timing matters too: cutting too early can lead to crumbly curds, while waiting too long risks a rubbery texture. Precision here is paramount, as it sets the stage for the curds’ transformation.

Stirring curds is both science and intuition. Gentle agitation keeps curds from clumping, ensuring uniform heat distribution and whey expulsion. For cheeses like Mozzarella, stirring is minimal to maintain elasticity, while cheeses like Swiss undergo vigorous stirring to reduce moisture and create a firmer base for bacterial activity. Temperature control during stirring is equally vital; a 1-2°C fluctuation can alter the curds’ behavior dramatically. Too hot, and the curds toughen; too cold, and whey retention increases. The goal is to coax the curds into releasing whey without compromising their integrity.

Heating curds is the final act in this delicate dance. For cheeses like Monterey Jack, curds are heated to 38-40°C to firm them up and expel residual whey, creating a semi-soft texture. In contrast, pasta filata cheeses like Provolone are heated to 60-70°C, stretching the curds to develop their signature fibrous structure. Overheating risks protein denaturation, leading to a grainy texture, while underheating leaves curds too moist. This step is where the cheese’s texture is sealed, making it a masterclass in precision and patience.

Mastering curd handling is less about following a script and more about understanding the curds’ response to each action. Observe how they firm up, how whey drains, and how they feel to the touch. For home cheesemakers, start with forgiving varieties like paneer or ricotta, where curd handling is simpler. Gradually experiment with harder cheeses, noting how cutting size, stirring intensity, and heating duration influence the outcome. The curds will tell you their story—if you learn to listen.

Cotija vs. Queso Fresco: Unraveling the Mexican Cheese Mystery

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Pressing & Molding: Shaping cheese by pressing curds into molds to remove excess whey

Cheese making is a delicate dance of science and art, and pressing and molding curds is a pivotal step that transforms a soft, whey-laden mass into a structured, recognizable cheese. This process is not merely about shaping; it’s about controlling moisture content, texture, and density, which directly influence the final product’s flavor and shelf life. Without proper pressing, cheeses like Cheddar or Gouda would lack their characteristic firmness and complexity.

Steps to Master Pressing & Molding:

- Prepare the Curds: After cutting and heating, curds are ready for pressing when they feel springy and release whey when squeezed. For harder cheeses, aim for a curd temperature of 38–40°C (100–104°F) before pressing.

- Choose the Right Mold: Select a mold that matches the cheese type. For example, a hoop mold is ideal for Cheddar, while a basket mold gives artisanal cheeses their distinctive rind patterns. Line the mold with cheesecloth for easy removal.

- Apply Pressure Gradually: Start with light pressure (2–5 kg) for the first 15–30 minutes to allow whey to drain freely. Increase pressure incrementally over 4–12 hours, depending on the cheese variety. Hard cheeses like Parmesan may require up to 20 kg of pressure.

- Flip and Repeat: Turn the cheese in the mold every 1–2 hours to ensure even moisture distribution and prevent sticking. For larger wheels, use a cheese press with adjustable weights for precision.

Cautions to Avoid Common Pitfalls:

Over-pressing can expel too much whey, leading to a dry, crumbly texture. Under-pressing leaves excess moisture, risking spoilage. Always follow a recipe’s timing and pressure guidelines. For beginners, soft cheeses like feta or paneer are forgiving and require minimal pressing (1–2 hours at 5–10 kg).

Takeaway: Pressing and molding is where cheese begins to take its identity. It’s a step that demands attention to detail but rewards with consistency and quality. Whether crafting a creamy Camembert or a sharp Cheddar, mastering this technique ensures every wheel or block meets its intended character. Experiment with pressure levels and mold types to discover how subtle changes yield distinct results.

What Does Cheese and Rice Mean in Text? Decoding the Phrase

You may want to see also

Aging & Ripening: Controlled storage to develop flavor, texture, and rind through microbial activity

Cheese aging, or ripening, is a delicate dance between time, temperature, and microbial life. This stage transforms a fresh, bland curd into a complex, flavorful cheese with a distinct texture and, often, a unique rind. The process relies on controlled storage conditions that encourage specific bacteria and molds to break down proteins and fats, releasing compounds that contribute to the cheese's character.

For example, a young cheddar aged for 2 months will have a mild, sharp flavor and a firm texture, while a cheddar aged for 2 years will develop a deep, nutty flavor and a crumbly texture.

The Art of Control:

Ripening requires precise control over humidity (typically 85-95%) and temperature (ranging from 4°C for hard cheeses to 12°C for soft cheeses). These conditions dictate the pace of microbial activity and the type of rind that develops. For instance, a washed-rind cheese like Epoisses is regularly brushed with a brine solution, encouraging the growth of Brevibacterium linens, responsible for its pungent aroma and orange rind. In contrast, a natural rind cheese like Camembert relies on the mold Penicillium camemberti, which thrives in cooler, damper conditions, resulting in a white, velvety exterior.

Beyond Flavor: While flavor development is paramount, ripening also significantly impacts texture. During aging, enzymes break down proteins, softening the cheese. This process is particularly evident in cheeses like Brie, where the interior becomes creamy and spreadable. Conversely, hard cheeses like Parmesan undergo a longer aging process, allowing for more extensive protein breakdown and moisture loss, resulting in a hard, granular texture.

The Time Factor: Aging times vary dramatically, from a few weeks for fresh cheeses like mozzarella to several years for aged goudas or cheddar. This extended period allows for the gradual development of complex flavors and textures. For home cheesemakers, patience is key. Regularly monitoring temperature and humidity, and observing changes in the cheese's appearance and aroma, are crucial for successful ripening.

Mastering the Microbiome: Understanding the specific microbial communities involved in ripening allows for greater control over the final product. Some cheesemakers use starter cultures containing specific bacteria strains to influence flavor profiles. Others encourage the growth of naturally occurring molds by controlling the environment. This intricate interplay between microorganisms and the cheese matrix is what makes ripening both a science and an art.

Global Cheese Leader: Which State Produces the Most Cheese Worldwide?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The main steps in cheese processing include milk preparation (pasteurization or raw milk), coagulation (using rennet or acid), cutting and stirring the curd, draining whey, salting, molding, pressing, and aging (ripening) to develop flavor and texture.

Pasteurization kills harmful bacteria in milk, making it safer for consumption, but it can also reduce the complexity of flavors in cheese. Some cheeses are made with raw milk to preserve natural enzymes and bacteria that contribute to unique flavors during aging.

Aging (ripening) allows cheese to develop its characteristic flavor, texture, and aroma. During this stage, bacteria and molds break down proteins and fats, and moisture evaporates, transforming the cheese from a fresh curd into a mature product. The duration of aging varies depending on the cheese type.