Cheese intolerance, though less discussed than lactose intolerance, is a notable concern for many individuals, stemming from difficulties in digesting specific components in cheese, such as lactose, casein, or histamine. While lactose intolerance affects a significant portion of the global population, particularly in regions with lower dairy consumption historically, cheese intolerance can manifest differently due to the fermentation and aging processes that reduce lactose content but increase histamine levels. This variability makes it challenging to pinpoint exact prevalence rates, but it is estimated that a considerable number of people experience discomfort after consuming cheese, ranging from mild bloating to more severe gastrointestinal symptoms. Understanding the underlying causes and mechanisms of cheese intolerance is crucial for those affected to manage their dietary choices effectively and maintain digestive health.

Explore related products

$15.99 $16.99

What You'll Learn

- Prevalence Rates: Global statistics on cheese intolerance and regional variations in occurrence

- Symptoms Overview: Common signs of cheese intolerance, including digestive discomfort and skin reactions

- Lactose vs. Dairy: Differences between lactose intolerance and broader dairy protein sensitivities

- Diagnosis Methods: Tests and approaches to identify cheese intolerance accurately

- Management Strategies: Dietary adjustments and alternatives for those with cheese intolerance

Prevalence Rates: Global statistics on cheese intolerance and regional variations in occurrence

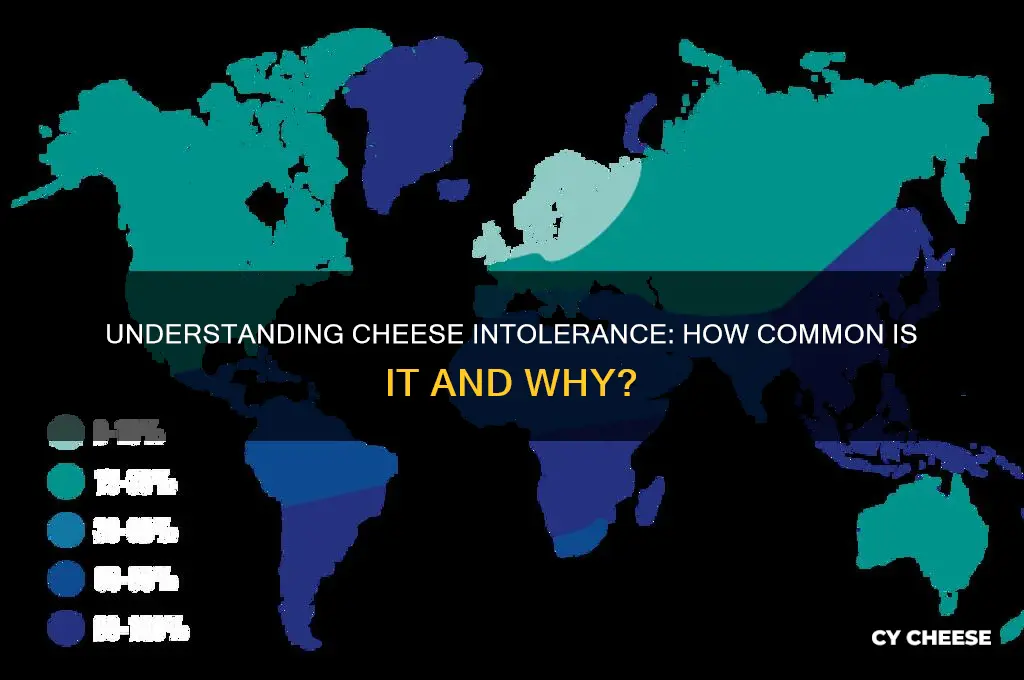

Cheese intolerance, primarily linked to lactose or casein sensitivity, affects a significant portion of the global population, though precise statistics are elusive due to underreporting and regional dietary variations. Estimates suggest that lactose intolerance impacts approximately 68% of the world’s population, with higher rates in Asia, Africa, and parts of South America, where dairy consumption is historically lower. However, cheese intolerance specifically is less studied, as many aged cheeses contain lower lactose levels, making them more tolerable for some individuals.

Regional variations in cheese intolerance prevalence are closely tied to genetic and dietary factors. For instance, Northern European populations, such as those in Scandinavia, exhibit lower intolerance rates (around 5%) due to genetic adaptations to dairy farming. In contrast, East Asian and Indigenous American populations show intolerance rates exceeding 90%, reflecting a lack of historical reliance on dairy. These disparities highlight how evolutionary dietary patterns influence modern tolerance levels, with cheese intolerance being more common in regions where dairy consumption is a recent dietary addition.

Analyzing specific age groups reveals further nuances in cheese intolerance prevalence. Infants and young children are naturally lactose tolerant, but rates of intolerance can rise with age, particularly in populations without a dairy-centric diet. For example, in some African countries, lactose intolerance emerges as early as age 5 in over 80% of children. Conversely, in Western countries, where dairy is a dietary staple, intolerance often develops later in adulthood, affecting approximately 15-20% of individuals over 50. This age-related shift underscores the interplay between genetics, diet, and gut health.

Practical tips for managing cheese intolerance vary by region, reflecting local dietary habits and available alternatives. In Asia, where intolerance is high, fermented dairy products like yogurt or plant-based cheeses (e.g., tofu-based options) are popular substitutes. In Europe, where aged cheeses like cheddar or Parmesan are lower in lactose, individuals often opt for these varieties in moderation. For those in regions with limited alternatives, lactase enzyme supplements can aid digestion, allowing for occasional cheese consumption without discomfort.

In conclusion, while global statistics on cheese intolerance remain fragmented, regional variations provide valuable insights into its prevalence. Understanding these patterns—shaped by genetics, diet, and age—can guide both individuals and healthcare providers in managing symptoms effectively. Whether through dietary adjustments, enzyme supplements, or alternative cheese options, tailored strategies can help mitigate the impact of cheese intolerance across diverse populations.

Dutch City Cheese: Discover the Edam and Gouda Connection

You may want to see also

Symptoms Overview: Common signs of cheese intolerance, including digestive discomfort and skin reactions

Cheese intolerance, though less discussed than lactose intolerance, affects a notable portion of the population, with symptoms often misunderstood or overlooked. Unlike a true allergy, which involves the immune system, cheese intolerance typically stems from the body’s inability to digest specific components in cheese, such as lactose, casein, or histamines. Recognizing the symptoms is the first step toward managing this condition effectively.

Digestive discomfort is the most common indicator of cheese intolerance, manifesting in ways that can range from mildly inconvenient to severely disruptive. Bloating, gas, and abdominal pain often occur within 30 minutes to 2 hours after consuming cheese. These symptoms arise because the digestive system lacks sufficient enzymes, such as lactase, to break down lactose, or struggles with proteins like casein. For instance, someone with a mild intolerance might experience slight bloating after a small serving of cheddar, while a more severe case could lead to cramping and diarrhea after just a few bites of blue cheese. Keeping a food diary can help pinpoint the correlation between cheese consumption and digestive issues.

Skin reactions are another telltale sign of cheese intolerance, though they are often misattributed to other causes. Conditions like eczema, hives, or acne may flare up after eating cheese, particularly in individuals sensitive to histamines or certain proteins. Histamine, a compound found in aged cheeses like Parmesan or Gouda, can trigger skin inflammation in those with histamine intolerance. Similarly, casein, a milk protein, has been linked to acne breakouts in some studies. If you notice recurring skin issues after consuming cheese, consider eliminating it from your diet for a few weeks to observe changes.

It’s important to distinguish cheese intolerance from other conditions, as symptoms can overlap with lactose intolerance, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), or even food allergies. For example, while lactose intolerance primarily causes digestive issues, cheese intolerance may also involve skin reactions or headaches. A practical tip is to test tolerance levels with different types of cheese—hard cheeses like Swiss have lower lactose content compared to soft cheeses like Brie, which may be better tolerated by some individuals. Consulting a healthcare provider for testing can provide clarity and rule out more serious conditions.

Managing cheese intolerance doesn’t necessarily mean eliminating cheese entirely. Many people find relief by opting for lactose-free or low-histamine varieties, or by reducing portion sizes. For instance, pairing cheese with digestive enzymes or consuming it alongside other foods can minimize discomfort. Additionally, fermented dairy products like kefir or yogurt may be better tolerated due to their probiotic content, which aids digestion. By understanding the specific symptoms and triggers, individuals can make informed choices to enjoy cheese without the unwanted side effects.

Troubleshooting Instant Pot Cheesecake: Why Your Crust is Falling Apart

You may want to see also

Lactose vs. Dairy: Differences between lactose intolerance and broader dairy protein sensitivities

Cheese intolerance often stems from two distinct issues: lactose intolerance and dairy protein sensitivities. Understanding the difference is crucial for managing symptoms effectively. Lactose intolerance occurs when the body lacks lactase, the enzyme needed to break down lactose, a sugar found in milk and dairy products. Symptoms like bloating, gas, and diarrhea typically appear 30 minutes to two hours after consuming lactose-containing foods. In contrast, dairy protein sensitivities involve an immune response to proteins like casein or whey, leading to symptoms such as hives, digestive discomfort, or even respiratory issues. While lactose intolerance is more common, affecting up to 70% of the global population, dairy protein sensitivities are less prevalent but can be equally disruptive.

To differentiate between the two, consider the type of dairy product and your reaction. Hard cheeses like cheddar or Parmesan are naturally low in lactose, making them better tolerated by those with lactose intolerance. However, they still contain dairy proteins, which could trigger a reaction in sensitive individuals. Soft cheeses, such as mozzarella or brie, retain more lactose and are more likely to cause issues for lactose-intolerant people. A practical tip: if you suspect lactose intolerance, try lactase enzyme supplements before consuming dairy to aid digestion. For protein sensitivities, elimination diets or allergy testing can help identify specific triggers.

Age and ethnicity play a significant role in lactose intolerance. It’s more common in adults, particularly those of East Asian, West African, Arab, Jewish, Greek, and Italian descent, where lactase production decreases after infancy. Dairy protein sensitivities, however, can affect anyone regardless of age or background. Children with conditions like eczema or asthma may be more prone to these sensitivities. If you’re unsure which condition you have, start by eliminating all dairy for two weeks, then reintroduce hard cheeses to test for lactose intolerance. If symptoms persist, consult a healthcare provider for further testing.

Managing these conditions requires tailored strategies. For lactose intolerance, opt for lactose-free dairy products or plant-based alternatives like almond or oat milk. Fermented dairy, such as yogurt or kefir, contains probiotics that can aid digestion. For dairy protein sensitivities, focus on non-dairy sources of calcium and protein, such as leafy greens, fortified beverages, and legumes. Reading labels is essential, as dairy proteins can hide in processed foods under names like "caseinate" or "whey powder." Keeping a food diary can also help track symptoms and identify patterns.

In summary, while lactose intolerance and dairy protein sensitivities both involve dairy, they differ in cause, symptoms, and management. Lactose intolerance is enzyme-related and often manageable with dietary adjustments or supplements, whereas dairy protein sensitivities involve immune responses and require stricter avoidance. Recognizing these distinctions empowers individuals to make informed choices and alleviate discomfort. Whether you’re reaching for a slice of cheese or a glass of milk, understanding your body’s reaction is the first step toward enjoying dairy—or finding suitable alternatives—without compromise.

Discover San Jose's Best Spots for Truffle Gouda Cheese

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Diagnosis Methods: Tests and approaches to identify cheese intolerance accurately

Cheese intolerance, often linked to lactose or histamine sensitivity, affects a notable portion of the population, with estimates suggesting up to 75% of adults worldwide may experience some form of lactose malabsorption. Identifying the root cause requires precise diagnostic methods to differentiate between intolerances and other conditions like allergies or irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Below, we explore the tests and approaches that accurately pinpoint cheese intolerance, ensuring individuals receive tailored dietary guidance.

Elimination Diet: The First Step in Suspicion

The most accessible and cost-effective method is an elimination diet, where cheese and dairy products are removed for 2–4 weeks. If symptoms like bloating, gas, or abdominal pain subside, cheese intolerance is likely. Reintroduce small amounts of cheese under controlled conditions to confirm. This approach is particularly useful for those suspecting histamine intolerance, as cheese is high in histamine. Keep a detailed food diary during this period to track reactions and identify patterns, ensuring accuracy in self-assessment.

Hydrogen Breath Test: Measuring Lactose Malabsorption

For lactose intolerance, the hydrogen breath test is a gold standard. After fasting overnight, the patient consumes a lactose-loaded drink (25 grams of lactose in water). Breath samples are collected at intervals to measure hydrogen levels. Elevated hydrogen indicates undigested lactose fermenting in the gut, a clear sign of lactose malabsorption. This test is non-invasive, suitable for adults and children over 5, and provides results within a few hours. However, it may yield false negatives in individuals with slow gut transit or those whose gut bacteria produce methane instead of hydrogen.

Blood Tests: Assessing Lactose Digestion

A less common but equally effective method is the lactose tolerance blood test. After consuming a lactose solution, blood samples are taken over 2 hours to measure glucose levels. If glucose levels rise minimally, it suggests impaired lactose digestion. This test is more invasive than the breath test and less practical for young children, but it offers a definitive biochemical marker of intolerance. It’s often used in conjunction with other tests for comprehensive diagnosis.

Genetic Testing: Uncovering Predispositions

For those seeking deeper insights, genetic testing can identify mutations in the LCT gene, which encodes lactase production. Reduced lactase activity is a primary cause of lactose intolerance, particularly in adulthood. While genetic testing doesn’t diagnose intolerance directly, it highlights predispositions, especially in populations with higher prevalence, such as East Asians, West Africans, and some Indigenous communities. This approach is valuable for long-term dietary planning but should complement functional tests for confirmation.

Practical Tips for Accurate Diagnosis

When pursuing diagnosis, avoid self-medicating with lactase supplements before testing, as they can skew results. Consult a healthcare provider to rule out conditions like celiac disease or inflammatory bowel disease, which share symptoms with cheese intolerance. For histamine intolerance, consider tracking other high-histamine foods (e.g., fermented products, cured meats) alongside cheese to identify broader patterns. Combining multiple diagnostic methods often yields the most accurate and actionable results.

By leveraging these tests and approaches, individuals can confidently identify cheese intolerance, paving the way for dietary adjustments that alleviate discomfort and improve quality of life.

Rhulk Cheese Patch: What's Changed in Destiny 2 Raids?

You may want to see also

Management Strategies: Dietary adjustments and alternatives for those with cheese intolerance

Cheese intolerance, often linked to lactose or casein sensitivity, affects a significant portion of the global population, with estimates suggesting up to 68% of adults have some degree of lactose malabsorption. For those affected, managing symptoms requires deliberate dietary adjustments and informed alternatives. The first step is identifying the specific trigger—lactose, casein, or both—through elimination diets or medical testing. Once confirmed, tailored strategies can be implemented to maintain nutritional balance while avoiding discomfort.

Step 1: Gradual Reduction and Substitution

Begin by reducing cheese intake rather than eliminating it abruptly. This allows the body to adapt while minimizing withdrawal symptoms like cravings or nutrient deficiencies. Substitute with lactose-free cheese options, which use lactase enzyme to break down lactose, or opt for naturally lower-lactose varieties like Swiss or cheddar. For casein intolerance, explore plant-based alternatives such as nut- or soy-based cheeses, ensuring they are fortified with calcium and vitamin B12 to mirror cheese’s nutritional profile.

Caution: Hidden Sources and Cross-Contamination

Cheese lurks in unexpected foods, from salad dressings to processed meats. Scrutinize labels for terms like "whey," "curds," or "caseinates." When dining out, communicate intolerance clearly, as cross-contamination in kitchens is common. For example, a seemingly safe dish might be garnished with grated cheese or prepared on surfaces used for cheese-containing items.

Analyzing Nutritional Trade-offs

Cheese is a rich source of calcium, protein, and vitamin D, so its removal necessitates strategic replacements. Incorporate calcium-fortified plant milks (aim for 120 mg per 100 ml), leafy greens like kale or broccoli, and almonds. For protein, lean on legumes, tofu, or quinoa. Vitamin D can be sourced from fortified foods or supplements, with adults typically requiring 600–800 IU daily. Consulting a dietitian ensures these adjustments meet individual needs.

Practical Tips for Long-Term Success

Experiment with homemade cheese alternatives, such as blending cashews, nutritional yeast, and garlic powder for a savory spread. Batch-cook meals to ensure cheese-free options are always available. Keep a food diary to track symptoms and identify tolerance thresholds—some individuals can handle small amounts of cheese without issue. Finally, embrace the opportunity to explore new flavors and cuisines, turning dietary restrictions into a culinary adventure rather than a limitation.

By combining gradual adjustments, vigilant label-reading, and creative substitutions, those with cheese intolerance can maintain a satisfying and nutritious diet without sacrificing health or enjoyment.

Does Your Liver Process Cheese? Understanding Digestion and Metabolism

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheese intolerance is relatively common, affecting a significant portion of the population. It is often linked to lactose intolerance or sensitivity to dairy proteins like casein.

Symptoms can include bloating, gas, diarrhea, stomach cramps, nausea, and skin issues. Severity varies depending on the individual’s level of intolerance.

Yes, cheese intolerance can develop at any age. It often arises due to reduced lactase production, the enzyme needed to digest lactose, or increased sensitivity to dairy proteins.

Diagnosis typically involves eliminating dairy from the diet to see if symptoms improve, or through tests like lactose tolerance tests, hydrogen breath tests, or food sensitivity panels. Consulting a healthcare professional is recommended.