Aged cheese, a culinary treasure revered for its complex flavors and textures, has a history deeply rooted in ancient practices. The origins of aged cheese can be traced back to early civilizations, where the need to preserve milk led to the discovery of fermentation and curdling techniques. Over time, these methods evolved as people observed that storing cheese in cool, humid environments allowed it to develop richer, more nuanced flavors. The process of aging cheese, also known as ripening, involves controlled conditions that encourage the growth of beneficial bacteria and molds, breaking down proteins and fats to create unique taste profiles. From the caves of Europe to modern cheese cellars, the art of aging cheese has been refined over centuries, transforming a simple dairy product into a sophisticated delicacy enjoyed worldwide.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Origin | Aged cheese likely originated in ancient times, possibly as early as 5000 BCE in the Middle East or Central Asia. |

| Discovery | Accidental discovery due to natural preservation of milk in animal stomachs (e.g., rennet) or storage in cool, humid environments. |

| Early Evidence | Archaeological findings suggest cheese-making in ancient Egypt (3000 BCE) and Mesopotamia. |

| Aging Process | Developed as a method to preserve milk, enhance flavor, and improve texture over time. |

| Historical Spread | Spread through trade routes, notably by the Romans, who popularized aged cheeses across Europe. |

| Key Regions | Early aged cheese production in regions like the Mediterranean, Middle East, and Central Europe. |

| Technological Advances | Use of salt, molds, and controlled environments (caves, cellars) to refine aging techniques. |

| Cultural Significance | Became a staple in diets and religious practices, symbolizing wealth and craftsmanship. |

| Modern Development | Industrialization and scientific understanding of microbiology further refined aging processes. |

| Notable Examples | Ancient aged cheeses include precursors to modern varieties like Cheddar, Parmesan, and Gouda. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Ancient Preservation Methods: Early civilizations used salting and drying to preserve milk, leading to cheese aging

- Accidental Discovery: Forgotten milk curds aged in caves, creating the first hard cheeses

- Monastic Traditions: Monks refined aging techniques, producing consistent, flavorful cheeses in European monasteries

- Trade and Spread: Aged cheese gained popularity through trade routes, becoming a prized commodity

- Industrial Revolution: Mass production and controlled environments standardized aged cheese manufacturing globally

Ancient Preservation Methods: Early civilizations used salting and drying to preserve milk, leading to cheese aging

The origins of aged cheese are deeply rooted in the necessity of food preservation. Early civilizations, faced with the challenge of storing perishable milk, turned to salting and drying as practical solutions. These methods not only extended the shelf life of milk but also inadvertently led to the creation of cheese, a discovery that would evolve into the art of aging. Salting, in particular, drew moisture from milk, inhibiting bacterial growth, while drying concentrated its nutrients, transforming it into a denser, more durable form. This dual approach laid the foundation for what would become one of humanity’s most cherished culinary traditions.

Consider the process of salting milk as a deliberate act of preservation. Ancient cultures, such as the Sumerians and Egyptians, applied salt in precise quantities—typically 2-5% by weight—to milk or curds. This concentration was sufficient to halt spoilage without rendering the product inedible. Over time, the salted curds would harden, creating a rudimentary form of cheese. Drying, often combined with salting, further reduced moisture content, making the cheese more resistant to mold and decay. These early experiments were not merely about survival; they were the first steps in understanding how time and treatment could enhance flavor and texture.

The transition from preserved milk to aged cheese was not immediate but rather a gradual refinement. As civilizations advanced, so did their techniques. The Romans, for instance, perfected the use of brine baths, submerging cheese in saltwater solutions to control moisture and salinity. This method allowed for longer aging periods, during which enzymes and bacteria could work their magic, developing complex flavors and aromas. Similarly, drying techniques evolved from sun-drying to controlled environments, such as caves or cellars, where temperature and humidity could be regulated. These innovations transformed cheese from a basic staple into a delicacy, prized for its depth and character.

To replicate these ancient methods today, start with fresh milk and add salt at a ratio of 2-3% by weight. Allow the mixture to curdle, then press and dry the curds in a well-ventilated area. For a more authentic experience, experiment with natural brining or air-drying in a cool, humid space. While modern tools like dehydrators or vacuum sealers can expedite the process, the principles remain unchanged. Patience is key, as aging cheese requires time—often months or even years—to achieve its full potential. The result is not just a preserved food but a testament to the ingenuity of our ancestors and their enduring legacy in the kitchen.

Perfect Cheese Ball Portions: Serving Size for a 10 oz Delight

You may want to see also

Accidental Discovery: Forgotten milk curds aged in caves, creating the first hard cheeses

The origins of aged cheese are deeply rooted in serendipity, a tale of forgotten milk curds left to mature in the cool, damp recesses of ancient caves. Imagine early herders storing curdled milk in animal stomachs or clay pots, only to rediscover it weeks later, transformed into a harder, more flavorful substance. This accidental discovery likely occurred in regions like the Fertile Crescent or the Mediterranean, where dairy farming and cave storage were common. The caves provided the ideal environment—consistent low temperatures and high humidity—for the curds to dry and age, developing the texture and complexity we now associate with hard cheeses.

To replicate this process today, start by curdling milk with rennet or acid, then draining the whey to form soft curds. Store these curds in a cool, humid environment, such as a basement or a wine fridge set to 50–55°F (10–13°C) with 85–90% humidity. Press the curds lightly to remove excess moisture, then let them age for weeks to months, depending on the desired hardness and flavor. For a cave-like atmosphere, wrap the cheese in cheesecloth or waxed paper and place it on a rack to allow air circulation. Regularly flip and inspect the cheese to prevent mold overgrowth, and consider experimenting with brine washes or natural molds like *Penicillium* for added complexity.

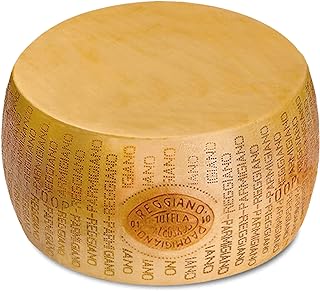

This method highlights the interplay between time, environment, and microbiology. As the curds age, lactic acid bacteria break down lactose and proteins, creating tangy flavors and a firmer texture. The cave’s natural molds and yeasts contribute unique characteristics, such as the earthy notes found in cheeses like Gruyère or Parmigiano-Reggiano. Modern cheesemakers often mimic these conditions using controlled aging rooms, but the essence remains the same: patience and the right environment are key. For home enthusiasts, a small investment in a humidity-controlled container or a DIY cave setup can yield remarkable results.

The takeaway is that aged cheese began not as a deliberate invention but as a happy accident, a testament to human adaptability and the transformative power of nature. By understanding the conditions that turned forgotten curds into culinary treasures, we can appreciate the artistry behind every wheel of aged cheese. Whether you’re a hobbyist or a professional, embracing this ancient process connects you to a tradition spanning millennia, proving that sometimes the best discoveries are the ones we least expect.

Cheese-Free Omelette Ideas: Tasty Substitutes for a Healthier Breakfast

You may want to see also

Monastic Traditions: Monks refined aging techniques, producing consistent, flavorful cheeses in European monasteries

The art of aging cheese owes much to the meticulous hands of European monks, whose monastic traditions transformed a simple preservation method into a culinary craft. Within the cloistered walls of monasteries, these religious communities developed techniques that not only extended the shelf life of milk but also enhanced its flavor, texture, and complexity. Their contributions laid the foundation for many of the aged cheeses we cherish today.

Consider the process of cheese aging, or affinage, as a delicate dance between time, temperature, and humidity. Monks, with their dedication to discipline and observation, mastered this dance. They discovered that controlled environments—cool, damp cellars—were ideal for slow maturation. By experimenting with different molds, bacteria, and aging durations, they created cheeses with distinct characteristics. For instance, the hard, granular texture of Parmesan emerged from months of careful drying and flipping, a technique honed in Italian monasteries. Similarly, the creamy interior and pungent rind of Brie can trace its origins to the practices of French monastic communities.

A key takeaway from monastic traditions is the importance of consistency. Monks documented their methods meticulously, ensuring that each batch of cheese was crafted with precision. Their attention to detail extended to the sourcing of milk, often from their own herds, and the use of specific starter cultures. This systematic approach not only guaranteed quality but also allowed for the replication of successful recipes across different monasteries. For modern cheesemakers, this serves as a reminder that consistency is as vital as creativity in producing exceptional aged cheeses.

To emulate monastic techniques, start by creating a stable aging environment. Aim for a temperature range of 50–55°F (10–13°C) and humidity levels between 85–95%. Use natural materials like wood or stone for aging rooms to promote proper air circulation and microbial growth. Experiment with different aging times—hard cheeses like Cheddar benefit from 6–24 months, while softer varieties such as Camembert mature in just 3–4 weeks. Regularly turn and brush the cheeses to prevent uneven mold growth and encourage rind development.

Finally, embrace the monastic spirit of patience and observation. Aging cheese is not a rushed process; it requires time and attentiveness to unlock its full potential. By adopting these time-honored practices, you can produce cheeses that are not only flavorful but also a testament to the enduring legacy of monastic craftsmanship. Whether you’re a hobbyist or a professional, the lessons from these ancient traditions remain remarkably relevant in today’s cheese-making world.

Mexican Salsa and Cheese Breakfast Burrito: Ingredients and Flavors Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Trade and Spread: Aged cheese gained popularity through trade routes, becoming a prized commodity

Aged cheese owes much of its global acclaim to the ancient trade routes that crisscrossed continents, transforming it from a local delicacy into a coveted commodity. The Silk Road, for instance, was not just a conduit for spices and silks but also for dairy innovations. Merchants traveling between Europe and Asia inadvertently facilitated the exchange of cheese-making techniques, including aging methods. As traders bartered goods, they also shared knowledge, allowing regions like the Mediterranean and Central Asia to refine their cheese-aging practices. This cross-cultural pollination laid the foundation for the diverse array of aged cheeses we enjoy today, from Parmigiano-Reggiano to Cheddar.

Consider the practicalities of trade: aged cheese was an ideal travel companion. Unlike fresh cheese, which spoils quickly, aged varieties could withstand long journeys due to their lower moisture content and natural preservatives like salt. This durability made them a valuable asset for traders, who could transport them across vast distances without significant loss. For example, Roman merchants carried Pecorino Romano, a hard sheep’s milk cheese, to feed legions stationed throughout the empire. Its longevity ensured soldiers had a reliable source of protein, while its robust flavor made it a prized item in trade negotiations.

The spread of aged cheese was also fueled by its role as a status symbol. In medieval Europe, aged cheeses like Gouda and Gruyère were luxury items, often reserved for the wealthy and nobility. Their scarcity and intricate production processes elevated their value, making them a sought-after commodity in trade fairs and markets. Merchants who specialized in these cheeses could command higher prices, further incentivizing their distribution. This economic dynamic not only popularized aged cheese but also spurred innovations in aging techniques, as producers sought to create more complex and desirable flavors.

To understand the impact of trade on aged cheese, examine the case of Cheddar. Originating in England, Cheddar became a global phenomenon through colonial trade networks. British settlers introduced it to North America, where local producers adapted the aging process to suit regional climates and tastes. Today, Cheddar is one of the most widely consumed aged cheeses worldwide, a testament to how trade routes can transform a regional specialty into an international staple. For enthusiasts looking to replicate this journey, start by sourcing raw milk and following traditional cheddaring techniques, then experiment with aging times—6 months for a mild flavor, 12 months for sharper notes.

In conclusion, the trade and spread of aged cheese highlight its evolution from a practical food source to a cultural and economic phenomenon. By tracing its journey along historic trade routes, we gain insight into how commerce, innovation, and cultural exchange shaped its popularity. Whether you’re a producer, trader, or connoisseur, understanding this history can deepen your appreciation for the artistry and legacy of aged cheese.

The Cheese-Obsessed One-Day Logic Prince: Unraveling the Mystery

You may want to see also

Industrial Revolution: Mass production and controlled environments standardized aged cheese manufacturing globally

The Industrial Revolution transformed aged cheese from a localized craft into a globally standardized product. Before this era, cheese aging was an art reliant on natural conditions—caves, cellars, or barns provided the necessary cool, humid environments, but results varied widely. The advent of mass production introduced controlled environments, where temperature, humidity, and airflow could be precisely regulated. This shift not only increased consistency but also scaled production to meet growing demand. Factories began replicating the conditions of traditional aging spaces, ensuring that a wheel of cheddar in England tasted the same as one produced in America.

Consider the process of aging cheese as a delicate dance of microbiology. In controlled environments, manufacturers could manipulate factors like temperature (typically 50–55°F for hard cheeses) and humidity (85–95%) to encourage the growth of specific molds and bacteria. For example, blue cheese requires higher humidity to foster *Penicillium roqueforti*, while Parmesan thrives in drier conditions. The Industrial Revolution’s machinery allowed for the mass replication of these environments, turning cheese aging from a gamble into a science. This precision not only improved quality but also reduced spoilage, making aged cheese more accessible and affordable.

However, standardization came at a cost. Traditional cheesemakers often argue that mass production sacrifices flavor complexity for consistency. Artisanal cheeses aged in natural environments absorb subtle nuances from their surroundings—a hint of earthiness from a cave or a tang from wooden shelves. In contrast, factory-aged cheeses, while reliable, can lack these unique characteristics. Yet, for a global market, consistency was key. By the mid-19th century, brands like Cheddar and Gouda became household names, their flavors recognizable across continents.

To understand the impact, compare the aging of a single wheel of cheese pre- and post-Industrial Revolution. Before, a cheesemaker might rely on a drafty cellar, hoping the temperature stayed below 60°F and the mold developed evenly. After, a factory could age thousands of wheels simultaneously in climate-controlled rooms, monitoring each stage with thermometers and hygrometers. This scalability allowed aged cheese to transition from a luxury to a staple, appearing on tables from Paris to New York.

Practical takeaways for modern cheesemakers or enthusiasts lie in balancing tradition and innovation. While controlled environments offer reliability, incorporating natural elements—like aging in wood or using raw milk—can reintroduce complexity. For home aging, invest in a wine fridge (set to 50–55°F) and a humidity tray filled with water to mimic industrial conditions. Monitor weekly, flipping the cheese to ensure even moisture distribution. The Industrial Revolution taught us that precision is power, but the soul of aged cheese still lies in its imperfections.

Distance from Heritage High School to Chuck E. Cheese: A Quick Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Aged cheese began as a method of preserving milk, with early evidence dating back to ancient civilizations like the Sumerians and Egyptians, who allowed cheese to naturally age to extend its shelf life.

The earliest methods involved storing cheese in cool, humid environments like caves or cellars, where natural bacteria and molds could develop over time, transforming the cheese’s texture and flavor.

People discovered that aged cheese developed richer flavors, firmer textures, and longer storage capabilities, making it a valuable food source during times when fresh milk was scarce.

The Romans are often credited with refining the aging process, as they developed techniques for controlling temperature, humidity, and mold growth, leading to more consistent and diverse aged cheeses.

Aged cheese spread through trade routes and cultural exchanges, with monasteries in Europe playing a significant role in preserving and advancing cheese-making techniques during the Middle Ages.