When hard cheeses are melted without an emulsifier, they separate into proteins and fats. This phenomenon has sparked curiosity among culinary enthusiasts, who wonder if the fat produced in this process can be used as cooking oil. While some find the idea unappetizing, others experiment with cooking techniques, adding cheese to hot pans to create crunchy cheese snacks or using the resulting oil to cook other foods. This exploration of cheese oil raises questions about its culinary potential and highlights the creativity of those seeking new ways to enjoy cheese.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| What is cheese? | An emulsion of dairy fat and water, held together by a network of proteins. |

| Why does cheese get oily? | When hard cheeses are melted without an emulsifier, they break into proteins and fats, resulting in a pool of oil. |

| How to prevent oil separation? | Use an emulsifier when melting cheese or cook at lower temperatures. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Hard cheeses melt into proteins and fats

Hard cheeses are a great source of protein and calcium. They are also often high in saturated fat and salt. This means that eating too much cheese could lead to high cholesterol and high blood pressure, increasing the risk of cardiovascular disease.

Hard cheeses, when melted without an emulsifier, break into proteins and fats. This fat can be used for cooking, as seen in some traditional recipes. For example, one can cook chicken in the oil rendered from melting a slice of provolone in a non-stick pan. However, it is important to note that hard cheeses tend to have more calcium than soft cheeses, and they also require more salt in the aging process, resulting in higher sodium content.

The protein found in cheese is called casein, and it is a type of protein that clumps together in families called micelles. Casein forms a gelled network that traps fats and liquids, resulting in the curds responsible for the majority of cheeses. When milk is heated with rennet, caseins form this gelled network instead of separating, resulting in the creation of cheese.

Cheese also contains other vital nutrients such as vitamins A and B12, phosphorus, potassium, zinc, and riboflavin. Some high-fat cheeses like blue cheese, Brie, and cheddar contain conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), which is a healthy fat that may offer benefits such as reducing the risk of obesity and heart disease. However, it is important to consume cheese in moderation as part of a balanced diet, especially for those with cardiovascular disease or high cholesterol.

Cleaning Burnt Cheese Off Your Oven: Easy Tips

You may want to see also

Acid-set cheeses don't melt

The meltability of cheese is influenced by several factors, including composition, acid levels, and age. Acid-set cheeses, such as fresh goat cheese, quick farmer's cheese, paneer, queso fresco, and ricotta, do not melt due to the presence of acids.

Cheese is an emulsion of dairy fat and water, bound together by a network of proteins called casein. During the cheesemaking process, casein proteins clump together in structures called micelles, which are held together by calcium and hydrophobic bonds. These bonds act like "seat belts and doors," ensuring that the proteins stay connected and secure.

However, in acid-set cheeses, the acids dissolve the calcium that holds the casein proteins together. This disruption prevents the cheese from melting smoothly. When an acid-set cheese is heated, the first thing to be released is water, rather than proteins. As the cheese continues to heat up, the proteins move closer together, and more water is cooked off. But without the calcium "glue," the cheese cannot melt.

Examples of acid-set cheeses that don't melt well include cottage cheese, chèvre (goat cheese), feta, ricotta, and paneer. These cheeses are excellent for cooking, grilling, roasting, and frying, as they hold their shape and don't melt when heated.

The Magic Behind Brazilian Cheese Bread Rising

You may want to see also

Melting cheese without emulsifiers

Cheese is an emulsion of dairy fat and water, held together by a network of proteins called casein. When hard cheeses are melted without an emulsifier, they break into proteins and fat. This can be done by heating the cheese in a non-stick pan until it becomes crunchy. However, this type of melted cheese is not suitable for use as a cooking oil.

Emulsifiers

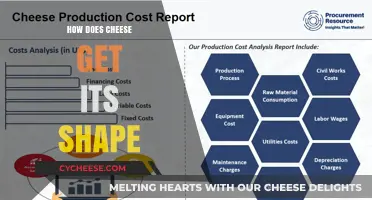

Emulsifiers are used to prevent the separation of melted cheese into a tough, stringy mass surrounded by a pool of oil. Common emulsifiers include sodium citrate, sodium hexametaphosphate, and sodium alginate. Sodium citrate is derived from citrus fruit and is effective at bonding with water and fats to create an emulsion. It also softens proteins and replaces some of the calcium bonds, allowing the fats and proteins to melt simultaneously. Sodium hexametaphosphate can be used alongside sodium citrate to improve the distribution of proteins and fats, resulting in a firmer final product. Sodium alginate is an emulsifying salt extracted from brown algae that helps create a stable emulsion.

Alternatives

If you don't have access to emulsifying salts, there are alternative methods to create a stable cheese sauce. One option is to use cornstarch and evaporated milk, which contains both emulsifying and stabilizing agents. Cornstarch acts as a thickening agent, preventing the sauce from becoming too liquidy. Another alternative is to use a roux, which can help preserve the texture of the sauce, including when reheating leftovers.

The Story Behind Philadelphia Cheese's Name

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Using cheese oil for cooking

When hard cheeses are melted without an emulsifier, they separate into proteins and fats. This fat can be used for cooking, although some people find the appearance off-putting. One user describes frying cheddar in a pan and then using the leftover oil to make a grilled cheese sandwich. Another user describes melting provolone in a non-stick pan until crunchy, then using the oil to cook chicken.

There are a few ways to make fresh cheese in oil with herbs. One method involves making fresh cheese from raw milk, cutting it into cubes, and then covering it in olive oil and herbs. Another method involves curing hard, dry cheeses such as Manchego or Parmesan in oil. The oil acts as a barrier against bacteria, keeping the cheese safe to eat for months or even years without refrigeration. After curing in oil for a month, the cheese takes on a soft texture and its flavour blends with that of the oil.

Cheese Heating: Killing Bacteria for Safe Consumption

You may want to see also

The science of melting cheese

Cheese is mostly made up of protein, fat, and water. The protein in cheese is called casein, which forms a 3D mesh that has calcium acting as the "glue" holding the casein micelles together. When milk is heated with rennet, the caseins form a gelled network that traps fats and liquids, rather than squeezing them out. These are the curds responsible for the vast majority of cheeses.

The melting properties of cheese depend on the temperature of its melting point. At about 90°F (32°C), the fat in cheese begins to soften and melt. Increasing the temperature by about 40-60 degrees causes the protein molecules to break apart and disperse throughout the fat and water. For the cheese to stay beautifully stringy and melty, the protein needs to stay evenly dispersed with the rest of the moisture and fat (an emulsion).

The composition of the cheese, the acid level in the cheese, and the age of the cheese are some of the biggest factors that influence how well a cheese will melt and stretch. Acid-set cheeses, like fresh goat cheese, quick farmers cheese, paneer, queso fresco, and ricotta, cannot melt because acid dissolves the calcium that holds the casein proteins together. As cheese ages, it loses moisture, and its proteins form tighter clumps, making them less effective at binding fat and water together. Therefore, younger, high-moisture cheeses like mozzarella, Taleggio, brie, Gruyère, Emmental, and Jack are more reliable melters, while drier grating cheeses like Parmesan or Pecorino-Romano often separate into clumps or even break.

To achieve the gooiest results, it is important to melt the cheese slowly and gently. When exposed to high heat, the proteins seize up and become firm, squeezing out moisture, and then separating. To prevent this, shred the cheese to expose more surface area so that it will melt more quickly, bring it to room temperature before heating, and use low, gentle heat.

Medieval Cheesemaking: Secrets of the Middle Ages

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

When hard cheeses are melted without an emulsifier, they break into proteins and fats. This is because milk's most crucial component, casein, is a type of protein that clumps together in families called micelles. Calcium and hydrophobic bonds act as the seat belts and doors of the cars, keeping everyone inside and secure. When cheese is heated, the caseins form a gelled network that traps fats and liquids, creating an emulsion of dairy fat and water.

To make cheese oil, hard cheeses are melted without an emulsifier until they separate into proteins and fats. The fat is then skimmed out and used as a cooking oil.

No, only hard cheeses can be used to make cheese oil. Acid-set cheeses like fresh goat cheese, farmer's cheese, paneer, queso fresco, and ricotta cannot be melted and therefore cannot be used to make cheese oil.

There are no specific traditional recipes mentioned, but some people like to add grated Parmesan or Romano to the oil until it forms a cheesy paste. Others like to fry an egg in the cheese oil or cook chicken in it.

Some people may enjoy the unique flavor that cheese oil adds to dishes. It can also be a way to make a dish more indulgent or luxurious, as it is more expensive than regular cooking oils.