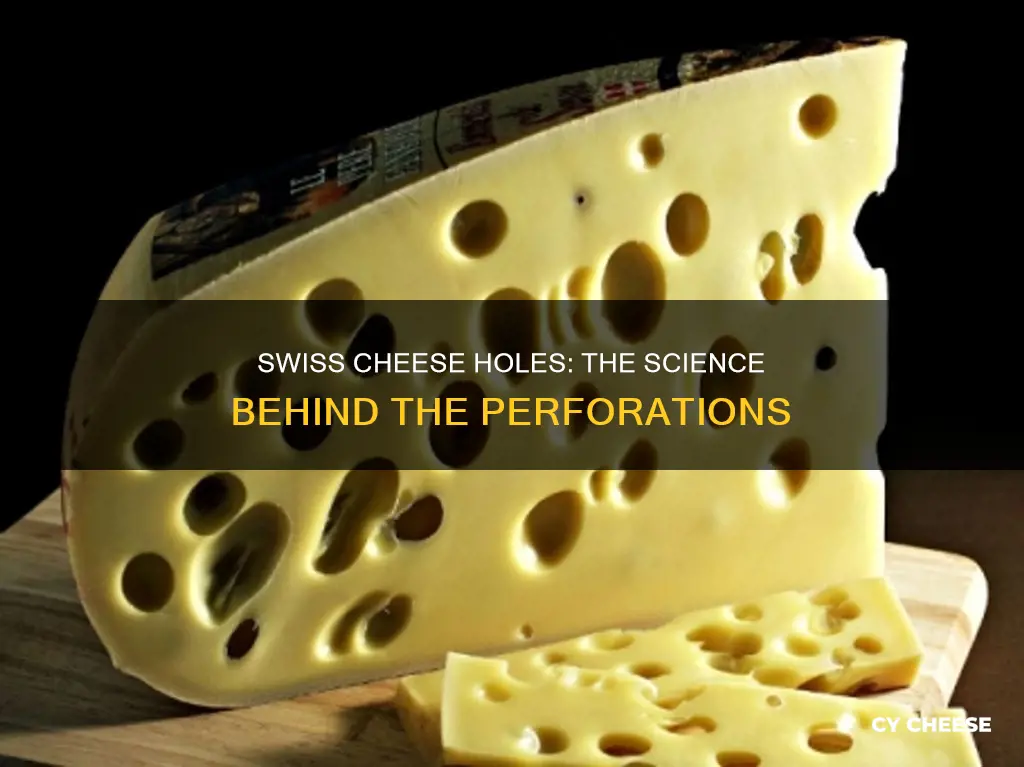

Swiss cheese is known for its distinctive holes, which are called eyes. The holes are formed by carbon dioxide gas produced by bacteria during the cheese-making process. The bacteria consume lactic acid and release carbon dioxide, which gets trapped in the cheese, forming bubbles that become the holes. The size of the holes can be controlled by adjusting factors such as temperature, storage time, and acidity levels. The presence of hay during the cheese-making process can also affect the size of the holes. While the exact science behind the formation of holes in Swiss cheese has been a topic of exploration, the combination of bacteria and carbon dioxide release is primarily responsible for creating the iconic holes in Swiss cheese.

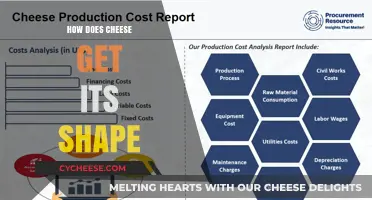

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reason for holes in Swiss cheese | Carbon dioxide gas produced by bacteria |

| Bacteria type | Propionibacterium |

| Bacteria source | Bacteria in milk, bacteria in grass and flowers consumed by cows, hay particles |

| Hole size influenced by | Temperature, storage time, acidity levels, humidity, fermentation times |

| Hole formation | Bubbles of carbon dioxide gas get trapped in cheese |

| Hole formation time | Weeks after cheesemaking |

| Hole formation conditions | High temperature |

| Hole absence | Modern milk extraction methods, cleaner processing centres |

| Hole presence | Elastic curd structure |

| Hole aesthetic | Unique and recognisable appearance |

| Hole taste contribution | Intricate, light, airy, nutty, flavour explosion |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The role of microbes and bacteria

The holes in Swiss cheese are a result of the bacterial strain Propionibacterium freundenreichii, which is added during the cheese-making process. This bacterium consumes lactic acid in the cheese and produces carbon dioxide gas, which forms air pockets or "eyes" within the cheese. The size of these holes depends on various factors such as temperature, humidity, fermentation time, and the length of the aging process.

The metabolic activity of these microbes produces hundreds of compounds from the protein and fat components in milk, affecting the flavor, aroma, texture, and color of the cheese. The carbon dioxide gas produced by the Propionibacterium bacteria collects at weak spots in the cheese, building up pressure until holes form. The propionate and acetate produced by these bacteria also contribute to the sweet and nutty flavor of Swiss cheese.

In addition to bacteria, yeast, and mold also play a role in the cheesemaking process. Yeast is commonly used in molded and surface-ripened cheeses and is naturally present in many natural rind cheeses. Molds, such as Penicillium camemberti, are added to the milk or curds to give cheese its characteristic white lawn and contribute to its texture and aroma.

The combination of bacteria, yeast, and mold, along with various environmental factors, creates the unique characteristics of Swiss cheese, including its iconic holes. The complex interplay of these microbes remains a subject of ongoing study in the field of microbiology.

Removing Mac and Cheese Stains: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Carbon dioxide gas

The basic theory regarding the formation of holes, or "eyes", in Swiss cheese and carbon dioxide is credited to William Mansfield Clark, a Department of Agriculture chemist. In 1912, he published "A Study of the Gases of Emmental Cheese", in which he captured gas using an apparatus of glass cylinders and mercury. Clark's idea that the holes in Swiss cheese were caused by carbon dioxide released by bacteria present in the milk was accepted as fact for almost 100 years.

However, in 2015, a study by Agroscope, a Swiss agricultural institute, challenged Clark's theory. Agroscope researchers attributed the formation of holes in Swiss cheese to tiny bits of hay present in the milk. They suggested that the disappearance of the traditional bucket used during milking resulted in fewer hay particles in the milk, leading to smaller holes or "blind cheese".

While the presence of hay particles may play a role in the development of holes, carbon dioxide gas is still involved in the process. Propionibacteria, one of the types of bacteria used in Swiss cheese production, consume the lactic acid excreted by other bacteria and release carbon dioxide gas. This gas slowly forms bubbles that develop the "eyes" in Swiss cheese.

McDonald's Cheese: Where Does it Come From?

You may want to see also

Propionic acid fermentation

In Swiss-type cheese, propionic acid fermentation is responsible for the distinctive nutty flavor and the formation of "eyes" or holes. During cheese manufacturing, lactic acid bacteria convert lactose into lactate. Then, during the ripening process, propionic acid bacteria convert the lactate into propionic acid, acetic acid, and carbon dioxide. The trapped carbon dioxide forms the holes in the cheese, and the propionic acid gives it its unique flavor.

Green Bean Casserole: Should You Add Cheese?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Modern methods of milk extraction

Milk for cheese-making is now usually extracted using modern methods, which might explain why Swiss cheese doesn't have as many holes as it used to. The process of cheese-making involves bacteria cultures that consume lactic acid in the cheese and produce carbon dioxide gas. A particular bacterial strain, Propionibacterium, is responsible for creating the bubbles that form the holes in Swiss cheese.

The original milking machine was a person, and milking cows by hand was the traditional method for thousands of years. However, with the advent of modern technology, milk extraction methods have evolved. Here are some modern methods of milk extraction:

- Milking Machines: In the 19th century, various types of milking machines were introduced to reduce the labour involved in hand milking. The pulsator milking machine, invented in 1895, improved the process by allowing the teat to fill up with milk intermittently. Over time, these machines became more efficient and affordable, leading to their widespread adoption. Modern milking machines use vacuum cups that attach to the cow's teats and automatically fall off once the quarter is milked dry.

- Cow Preparation: Before using a milking machine, it is important to secure the cow's head to prevent it from wandering off. The cow's udder should be cleaned and lubricated, and its teats disinfected to prevent bacterial infections.

- Milk Collection and Storage: Milk extracted from the cow is collected in stainless steel pipes and stored in refrigerated vats at temperatures below 5°C. Within 48 hours, the milk is transported to a milk factory for further processing.

- Pasteurisation: Pasteurisation involves heating the milk to 72°C for at least 15 seconds and then immediately cooling it to destroy harmful bacteria and microorganisms. This process extends the shelf life of the milk.

- Homogenisation: Milk is passed through fine nozzles under pressure to evenly disperse fat globules and prevent the cream from separating and rising to the top. This results in a consistent texture and taste.

- Standardisation: Milk composition is standardised to ensure consistency in elements like fat content, regardless of the season or breed of cow. This standardisation is governed by food standards codes to maintain safety and nutritional value.

- Ultrafiltration: Some manufacturers use ultrafiltration to standardise milk year-round. This process involves passing milk through a fine membrane filter to separate certain elements, resulting in a consistent product.

Calus Cheese: Did Bungie Patch the Exploit?

You may want to see also

The cheese-making process

Swiss cheese, or Emmental, is a medium-hard cheese that originated in Switzerland and is known for its distinctive holes, texture, and flavour. The cheese-making process for Swiss cheese involves several steps that contribute to the formation of these holes. Firstly, fresh milk is sourced and combined with good bacteria to form curds. These curds are then soaked in a brine solution, which is a mixture of salt and water. During this stage, the bacteria expand and release carbon dioxide, creating the foundation for the holes.

The temperature, humidity, and fermentation times play a crucial role in the cheese-making process, influencing the size and distribution of the holes. The cheese is subjected to multiple heating and cooling cycles, and the carbon dioxide released by the bacteria forms air pockets within the cheese. These air pockets eventually become the holes in the Swiss cheese.

The holes in Swiss cheese, also known as "eyes," vary in size and distribution across different varieties. Factors such as hay particulates, which create weaknesses in the curd structure, can affect the size of the holes. Modern processing centres have reduced the presence of hay particulates, resulting in smaller holes compared to the larger eyes found in traditional Swiss cheese.

The bacterial strain Propionibacterium, specifically Propionic Shermanii, plays a significant role in the cheese-making process. These bacteria consume lactic acid and transform it into carbon dioxide. The carbon dioxide gas accumulates and forms the iconic holes in Swiss cheese. The maturation process, overseen by an affineur, takes approximately six to eight months until the Swiss cheese is ripe and ready for consumption.

The History Behind the Name of Muenster Cheese

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The holes in Swiss cheese, also known as "eyes", are caused by carbon dioxide released by bacteria present in the milk.

The holes are created by a particular bacterial strain known as Propionibacterium.

The bacteria consume lactic acid and produce carbon dioxide gas, which gets trapped in the cheese, forming bubbles that we call "holes".

Yes, the holes contribute to the cheese's nutty taste and light, airy feel.

According to the Agroscope Institute for Food Sciences, the holes have gotten smaller due to cleaner processing centres, which allow fewer and smaller hay particulates into the cheese.