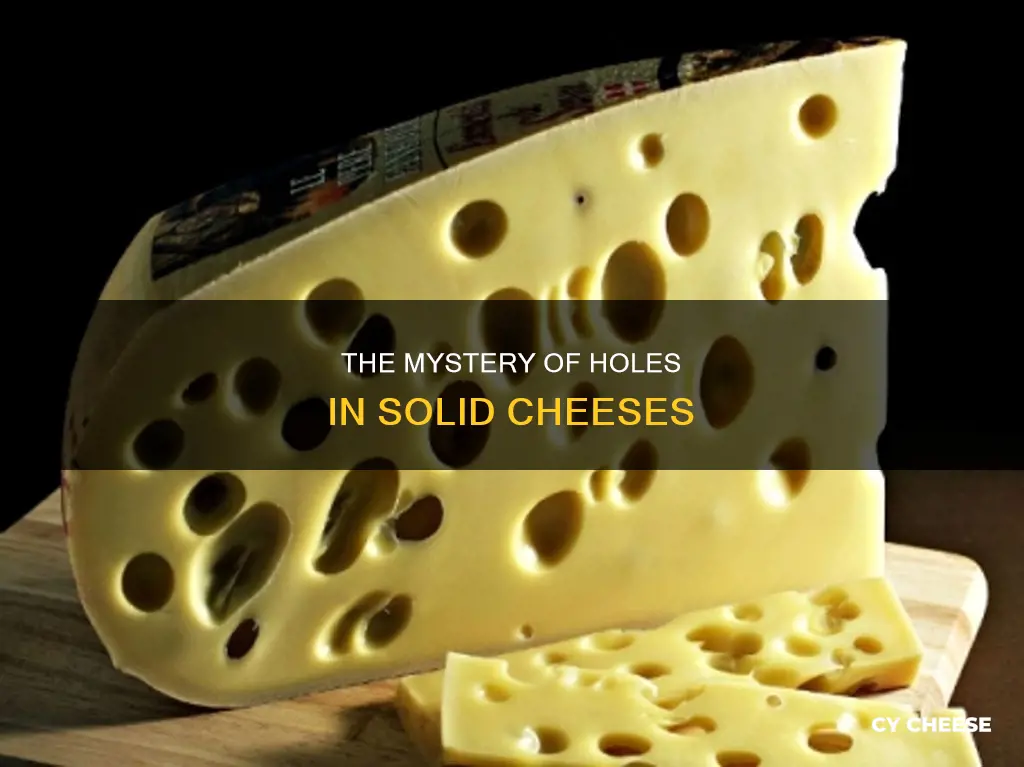

Swiss cheese is known for its distinctive holes, which are primarily caused by bacteria cultures that play a significant role in the cheese-making process. These bacteria, specifically Propionibacterium, consume lactic acid in the cheese and produce carbon dioxide gas, which gets trapped, forming bubbles that we call holes. The size and distribution of these holes are influenced by factors such as temperature, humidity, and fermentation times. The holes in Swiss cheese contribute to its mouthwatering, slightly nutty taste, light and airy feel, and unique appearance, making it a beloved and recognizable delicacy worldwide.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reason for holes in solid cheese | Bacteria cultures consume lactic acid in the cheese and produce carbon dioxide gas, which gets trapped, forming bubbles or holes |

| Type of bacteria | Propionibacterium |

| Size of holes | Influenced by temperature, humidity, and fermentation times |

| Traditional method of making cheese | In barns using open buckets, allowing hay particles to enter the collected milk |

| Modern method of making cheese | Using advanced equipment, such as turning machines or fully automated systems |

| Impact of holes | Contribute to the cheese's nutty taste, light and airy texture, and unique appearance |

Explore related products

$23.99

What You'll Learn

Bacteria and carbon dioxide

The presence of bacteria and carbon dioxide is integral to the formation of holes in Swiss cheese. The process of cheesemaking involves the addition of starter cultures or bacteria cultures, which contain bacteria. These bacteria consume lactic acid, a byproduct of lactose in the milk, and produce carbon dioxide gas as a result. The carbon dioxide gas released by the bacteria gets trapped within the cheese, forming bubbles that eventually become the holes characteristic of Swiss cheese.

The specific bacterial strain responsible for creating these holes is Propionibacterium. These bacteria are microscopic, gram-positive, and non-motile. They play a unique role in transforming the lactic acid into carbon dioxide gas. The carbon dioxide gas forms bubbles that get trapped within the cheese, creating the holes or "eyes" commonly associated with Swiss cheese.

The size and distribution of the holes in Swiss cheese are influenced by various factors during the cheese-making process. Temperature, humidity, and fermentation times all play a role in determining the final size and pattern of the holes. The traditional method of using open buckets for cheese-making also contributed to the formation of holes. Hay particles would fall into the buckets and create weaknesses in the curd structure, allowing gas to form and expand, thus creating larger holes.

In recent years, the holes in Swiss cheese have become smaller or even nonexistent due to changes in the cheese-making process. The disappearance of the traditional bucket used during milking has resulted in fewer hay particles contaminating the milk. Modern extraction methods have reduced the presence of foreign particles, leading to a decrease in the size and occurrence of holes in Swiss cheese.

While the role of bacteria and carbon dioxide in hole formation is well-established, it is important to note that other factors, such as the specific cheese-making techniques and environmental conditions, also contribute to the unique characteristics of Swiss cheese. The combination of bacterial activity, gas formation, and external factors results in the delightful texture and aesthetic appeal of Swiss cheese, making it a beloved and recognizable delicacy worldwide.

Can Salmonella Lurk in Your Cheese?

You may want to see also

Hay particles in milk

The presence of holes in cheese, also known as "eyes", has long been a mystery, with a common old wives' tale blaming mice for chewing the holes. In 1917, William Clark published a theory that the holes in Swiss cheese were caused by carbon dioxide released by bacteria present in the milk. This idea was widely accepted until it was debunked by a study in 2015.

Scientists from the Agroscope Institute for Food Sciences and the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology have revealed that the holes in Swiss cheese are caused by hay particles in the milk used for cheese-making. The traditional method of cheese-making involved open buckets, which allowed hay particles to fall into the milk. These particles created weaknesses in the structure of the curd, allowing gas to form and create holes.

The researchers conducted experiments using microfiltered milk with controlled amounts of hay powder added. They found a significant relationship between the amount of hay powder and the number of holes formed. By controlling the number of hay particles, the scientists could regulate the formation of holes in the cheese.

In recent years, the milk used for cheese-making is collected using modern methods, such as sealed milking machines and fine-pored filters, which prevent hay particles from entering the milk. This has resulted in a decrease in the number of holes in Swiss cheese varieties like Emmentaler, Tilsiter, and Appenzell.

To preserve the traditional characteristics of Swiss cheese, some experts recommend that cheese producers add hay particles during the cheese-making process to induce the formation of eyes. This controlled addition of hay powder harnesses a naturally occurring phenomenon rather than artificial seeding.

Mac & Cheese Journey: From Factory to Grocery Store

You may want to see also

Microbes and lactic acid

Microbes, or microorganisms, are an essential component of cheese and are responsible for much of its unique character. In cheese, we usually find bacteria, yeasts, and moulds. Microbes are added to the milk early in the cheese-making process to induce fermentation. This process involves the conversion of lactose to lactic acid, acidifying the milk. These microbes are often referred to as "starter cultures". Examples include Lactococci, Streptococci, and Lactobacilli, which are used in cheeses like cheddar, mozzarella, and Swiss cheeses.

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) play a critical role in traditional cheese-making, either as starter cultures or as secondary agents during cheese ripening. They contribute to the development of desirable sensory characteristics and enhance the nutritional value of the cheese. LAB causes the rapid acidification of milk through the production of organic acids, primarily lactic acid. This acidification inhibits the growth of unwanted microbes, preserving the milk as cheese and preventing spoilage.

The acid produced during fermentation also helps form curds and contributes to the removal of water from milk proteins. The milk is warmed to the optimal growth temperature of microbes, typically between 70–90°F, to increase the rate of fermentation. This warming process further contributes to the conversion of lactose to lactic acid.

In Swiss cheese, the bacteria Propionibacterium freundenreichii converts lactic acid into propionic acid, acetic acid, and carbon dioxide gas. This gas collects at weak spots in the cheese, building up pressure until holes, also known as "eyes," form. If these holes do not appear, the cheese is referred to as "blind." The presence of these holes is influenced by the milk composition, techniques used during cheese-making, and the specific microbes involved.

The Mystery of Asiago Cheese Holes Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Propionibacterium

The holes in Swiss cheese, also known as "eyes", are formed by carbon dioxide released by bacteria present in the milk. Specifically, the bacteria responsible for the holes are Propionibacterium freudenreichii, a Gram-positive, non-motile, anaerobic rod-shaped bacterium. P. freudenreichii is one of the three primary types of bacteria used to make Swiss cheese, the other two being Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus helveticus.

P. freudenreichii ferments lactate to form acetate, propionate, and carbon dioxide. The carbon dioxide forms bubbles within the cheese, which are left in as the cheese ferments, creating the holes. The size of the holes can be controlled by changing the acidity, temperature, and curing time during the fermentation process.

P. freudenreichii is also responsible for the nutty and sweet flavours characteristic of Swiss cheese. The acetate, propionate, and propionic acid produced by the bacterium contribute to this flavour profile. In addition to its role in cheese-making, P. freudenreichii has been isolated from soil and is known to have probiotic properties, such as high resistance to gastric acids and bile salts.

While P. freudenreichii is the most common bacterium associated with Swiss cheese, other species of Propionibacterium are also used in cheese-making, including P. thoenii, P. jensenii, and P. acidipropionici. These bacteria are often referred to as dairy propionic acid bacteria (PAB) and are known for their unique metabolism, which involves the production of propionic acid using transcarboxylase enzymes.

Swiss Cheese Holes: A Mystery Solved

You may want to see also

Starter cultures

On a molecular level, starter cultures ferment the lactose in milk and convert it to lactic acid. Lactic acid bacteria rely on lactose fermentation for energy. The formation of lactic acid creates an acidic (low pH) environment in the milk in which only certain bacteria can survive. Therefore, this process favours the spread of desirable lactic acid bacteria and eliminates other potentially harmful microorganisms.

The specific tasks of starter cultures mean that they need to have a healthy population so they are more competitive than undesirable bacteria that could contaminate the milk, curds, or cheese. The varying strains of LAB starter cultures will determine the final results of the cheese. Once the lactose has been converted, there is minimal food remaining for the bacteria to sustain their population. But, even as they begin to die off, their work is not done. As the bacteria die, their cell structure breaks down and very specific enzymes are released into the cheese. These enzymes can contribute many good things to the cheese, including diacetyl, which adds a butter-like flavour, or small amounts of CO2, which creates a more open cheese body.

The bacteria and fungi present in the starter also leave an imprint on the cheese's flavour and texture. Leuconostoc, for example, will aid in the production of CO2 gas, which contributes to a substantial number of small holes and a more open texture in the final cheese. This group of cultures produces a more open and buttery texture in the final cheese and is used when making Brie, Camembert, Gouda, Blue, and Havarti, among others.

Green Bean Casserole: Should You Add Cheese?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The holes in solid cheese are primarily due to a particular bacterial strain known as Propionibacterium. These bacteria consume lactic acid and transform it into carbon dioxide. This gas gets trapped, forming bubbles that we call "holes."

Temperature, humidity, and fermentation times all play a role in determining the size and distribution of the holes in the cheese-making process.

No, not all Swiss cheeses have holes. Some varieties of Swiss cheese, such as Emmental and Gruyère, do not have the signature holes.