Making cheese from milk is a great way to save money and learn a new skill. It's a simple process that can be done with a gallon of milk and some basic supplies. The first step is to heat the milk, either by obtaining it directly from a cow or by slowly warming it on a stove. The next step is to acidify the milk, which can be done by adding vinegar or citric acid, or by adding cultures and allowing them to turn the lactose into lactic acid. Once the milk has reached the correct acidity, a coagulant like rennet can be added to cause the proteins to link together and form a gel. Finally, the curds are separated from the whey and salt is added to taste. With these steps, anyone can make delicious homemade cheese from milk!

How to get cheese from milk

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Milk type | Raw, non-homogenized milk is best. Store-bought milk should be pasteurized, homogenized, non-homogenized, pasture-raised, or raw. Avoid ultra-pasteurized milk. |

| Milk temperature | Heat milk to 195°F (90°C) for direct acidification or leave at room temperature if adding cultures. |

| Acid type | Vinegar (white or apple cider), citric acid, or lemon juice. |

| Amount of acid | 1/4 to 1/8 cup of vinegar for 1 gallon of milk. |

| Coagulant | Rennet, an enzyme that causes milk proteins to link together. |

| Curd size | Smaller curds result in drier, more ageable cheese. Larger curds retain more moisture. |

| Stirring | Stir curds for several minutes to an hour, depending on the recipe. |

| Washing | Remove some whey and replace with water for a milder, sweeter, and more elastic cheese. |

| Salting | Add salt after separating curds from whey or after pressing the cheese into a wheel. |

| Storage | Wrap in plastic and store in the refrigerator. Fresh cheese lasts about 1 week. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Heating milk to the right temperature

To make cheese from milk, one of the first steps is to heat the milk to the right temperature. This can be done by transferring the milk from the fridge into a large pot and warming it slowly on the stovetop. It is important to stir the milk constantly to prevent scorching on the bottom. The ideal temperature for making cheese from milk is around 195 degrees Fahrenheit (90 degrees Celsius). However, some recipes may call for slightly higher temperatures, up to 198 degrees Fahrenheit.

It is important to note that the type of milk used can also affect the cheese-making process. Raw, non-homogenized milk is considered the best option for making cheese. This type of milk has not been pasteurized or homogenized, which means it retains more of the natural enzymes and bacteria that are important for cheese-making. Store-bought milk can also be used, but it is important to avoid milk that is labelled as "ultra-pasteurized". If using store-bought milk, you may need to add Calcium Chloride to make up for the calcium lost during pasteurization.

Additionally, the temperature of the milk can affect the cheese-making process. Starting with cold milk will require more time to reach the desired temperature, while room-temperature or warm milk will reach the desired temperature faster. Leaving milk out at room temperature overnight can help speed up the cheese-making process. However, it is important to note that milk that is too hot can kill the good bacteria needed for cheese-making.

Once the milk has reached the right temperature, the next step is to add an acid or a coagulant to start the cheese-making process. This can be done by adding vinegar, citric acid, or rennet, which is an enzyme that causes the proteins in milk to link together and form curds. The type and amount of acid added can vary depending on the desired type of cheese and the specific recipe being followed.

Overall, heating milk to the right temperature is a crucial step in the cheese-making process. It helps to create the ideal conditions for the milk to transform into cheese, and it can also affect the texture and moisture content of the final product. By carefully controlling the temperature and following the subsequent steps, anyone can make delicious homemade cheese.

Cheese Certification: A Guide to Getting Accredited

You may want to see also

Adding an acid to milk

To start, heat the milk to around 100°F. This creates an environment where lactic acid bacteria can thrive. Then, add an acid such as lemon juice or vinegar to the heated milk, which will curdle the milk. The amount of acid added is important, as it determines the acidity of the cheese. The cheese will also absorb some flavour from the acid.

After adding the acid, the milk will separate into two halves: curds and whey. The curds are solid, while the whey is liquid. The curds can then be cut into smaller cubes or chunks, which affects the amount of moisture retained in the final cheese. Smaller curds will result in a drier and more ageable cheese.

Once the curds have been separated from the whey, salt can be added. The curds can also be moved into their final forms or baskets and pressed into a wheel before salting. If the cheese is properly acidified and has the correct amount of moisture, it can be aged to develop a more complex flavour and texture.

Can Salmonella Lurk in Your Cheese?

You may want to see also

Adding cultures or bacteria to milk

The process of making cheese involves acidifying the lactose sugar within milk, turning it into lactic acid. This step is essential for setting the milk into curds, giving flavour to the cheese, and making it long-lasting and safe to eat. This process requires bacteria, specifically lactic acid bacteria (LAB). LAB is added to milk to break down the lactose (a natural sugar found in milk) and transform it into lactic acid. This process is called direct acidification and results in cheeses such as ricotta and mascarpone.

LAB can be purchased in sachets, called "starter cultures", which are well-tested and help produce consistent cheese results. The availability of these off-the-shelf starter cultures has improved cheese consistency and flavour. However, it is important to note that these sachets contain bacteria that may not be natural to the cheese-maker's area and milk. On a large scale, using bought-in cultures is essential when milk is sourced from multiple farms and is pasteurised, as the cheese-maker needs to repopulate the milk with LAB.

Alternatively, some cheese-makers, particularly those on the European mainland, make their own starter cultures. This involves allowing the milk to express itself and letting the bacteria it naturally contains grow. This results in a natural cheese that is completely unique to the cheese-maker and the farm.

The addition of adjunct cultures, which are selected from adventitious LAB or non-starter LAB (NSLAB), can also be used to accelerate the ripening process and produce the desired flavour. These cultures are chosen to survive cheese curd cooking temperatures and contribute to flavour development during cheese ripening.

Overall, the addition of cultures or bacteria to milk is a crucial step in the cheesemaking process, as it not only initiates the transformation of milk into cheese but also helps to develop its distinct texture, flavour, and aroma.

How to Clean Grana Padano Cheese Bowls?

You may want to see also

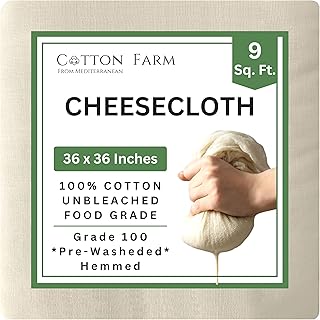

Explore related products

Cutting curds into smaller pieces

Once the milk has been acidified and the curds have formed, it is time to cut the curds into smaller pieces. This is the first step in reducing the curd moisture. The size to which you cut the curds will impact the amount of moisture retained in your final cheese; the smaller the initial pieces, the drier (and more ageable) the cheese will be.

To cut the curds, you can use a proper cheese curd cutter, a long blade, a straight-edge knife, or a palette knife. Begin by cutting the curd mass as evenly as possible into small pieces, about 3/8” to 3/4" in size. You can also tear the curd into thumb-sized pieces. Be careful and precise when cutting the curds to ensure they are all roughly the same size. If you are making a harder cheese like Parmesan, you may need to use a whisk to reduce the curds to a smaller size after the initial cutting.

After cutting the curds, allow them to rest for about 10 minutes. During this time, the cut curd surfaces will "heal," and the curds will become very fragile and prone to breaking. Next, begin to stir the curds slowly while raising the temperature to 95°F during the first 15 minutes. This will help the curd surfaces firm up and prevent breaking.

As you stir, the curds will continue to dry out, and the acid within them will continue to develop. You may also turn on the heat and cook the curds while stirring. This process will depend on the specific recipe you are following.

Getting Cheese Coins: Transformice Strategy Guide

You may want to see also

Washing and separating curds from whey

To make cheese, milk is separated into curds and whey. The curds are the result of milk proteins solidifying, and the whey is the off-white to yellow liquid left behind.

Washing is the process of removing some of the whey from the vat and replacing it with water. This creates a milder, sweeter, and more elastic cheese. To wash and separate curds from whey, follow these steps:

First, wait for the milk to transform from a liquid into a gel. You can test this by pressing on the surface of the milk with a clean finger. The gelled milk must break cleanly, meaning that your finger is not covered in milk, and the split on the surface holds its form after you remove your finger.

Next, cut the curd down from a giant blob into smaller cubes or chunks. You can use a cheese harp, a knife, or a whisk for this. The smaller the initial pieces, the drier and more ageable the cheese will be.

Stir the curds in the vat for several minutes or up to an hour, depending on the recipe. You may turn on the heat and cook the curds while stirring. During this phase, acid continues to develop inside the curd, and the curds dry out due to the stirring motion.

Once the curds are ready, you can separate them from the whey by dumping the contents of the pot into a colander in the sink. Let the curds settle for about 10 minutes, then press them together at the bottom of the pot before bringing them up and out of the pot in chunks. It is important to work quickly at this point to conserve the heat in the curds, encouraging them to form a smooth wheel. If you wait too long, the curds will get cold, and the cheese will fall apart.

After separating the curds from the whey, you can add salt to the curds or move them into their final forms or baskets. You can also press the cheese into a wheel before salting.

Cheese Spoilage: How Long Does it Last?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

You can use raw, non-homogenized milk, or store-bought milk that is pasteurized, homogenized, non-homogenized, pasture-raised, or raw. Avoid using ultra-pasteurized milk.

Warm the milk in a large pot on the stove until it reaches 195°F (90°C), stirring constantly. If using store-bought milk, add Calcium Chloride to make up for the calcium lost during pasteurization.

Once the milk is warmed, add an acid (vinegar or citric acid) to the milk to get the correct acidity. You can also add cultures or living bacteria, which will turn the lactose in the milk into lactic acid. Then, add rennet, an enzyme that will cause the milk to transform from a liquid into a gel. Once the gel has formed, cut it into small cubes or chunks, and stir for several minutes to draw out the moisture. Finally, separate the curds from the whey by dumping the contents of the pot into a colander, then add salt to taste.