Making cheese at home is a fun and rewarding hobby that anyone can try. It's a great way to get creative in the kitchen and learn about the ancient craft of cheesemaking. To get started, you'll need some basic ingredients and equipment, such as milk, vinegar, and salt. You can also invest in a cheese press or rig up a simple press using household items like cutting boards and milk jugs filled with water. Familiarize yourself with the steps of the cheesemaking process, including heating milk, adding an acidifier, cutting and stirring curds, and drying and ageing your cheese. With a little patience and practice, you'll be well on your way to crafting delicious homemade cheeses.

How to get started making cheese

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Milk | The fresher the milk, the better the cheese. Milk can be sourced from cows, goats, and sheep. |

| Heating milk | Heat milk in a large pot to 195°F (90°C), stirring constantly to prevent scorching. |

| Acidifying milk | Add vinegar, lemon juice, citric acid, or lactic acid directly to milk or add cultures (bacteria) to acidify the milk. |

| Curds | Cut the curds into smaller cubes or chunks using a knife, whisk, or 'cheese harp'. Stir the curds for several minutes to an hour, depending on the recipe. |

| Salt | Salt is added to the curds once they are separated from the whey. Salt acts as a natural preservative and enhances flavor. |

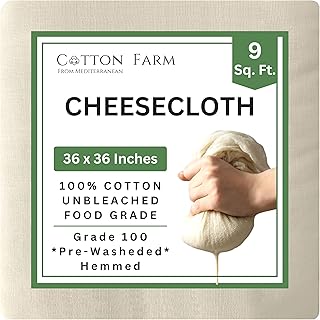

| Cheesecloth | Use cheesecloth or butter muslin to drain the curds and remove excess moisture. |

| Pressing | Place the curds into a cheese press or a basket and press into a wheel. |

| Aging | Cheese can be aged in a dedicated aging space, an old ice chest, a back closet, or a refrigerator drawer. |

| Starter kits | Beginner cheese-making kits are available for mozzarella, ricotta, mascarpone, and more complex varieties. |

| Recipes | Simple recipes for homemade cheese include queso fresco, ricotta, mascarpone, and paneer. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Choosing milk: raw vs. pasteurized

When it comes to choosing milk for cheese-making, you can use either raw or pasteurized milk. There are benefits and drawbacks to both.

Raw milk contains all the natural cultures needed to make cheese. The microbes to make everything from Parmesan to Brie are in that cup of fresh milk, and the type of cheese is determined by how you treat the curds. Raw milk is usually sold within 48 hours of milking the animal, and its flavour varies throughout the season, depending on the animal's diet. This can add a hint of grass, clover, or alfalfa to your cheese. However, raw milk can be difficult to find and is often twice as expensive as pasteurized milk. It also carries some health risks, as it can contain pathogenic bacteria.

Pasteurized milk, on the other hand, is more widely available and less expensive. It also carries fewer bacteria, so the cheese culture has little competition and can lead to a more consistently flavoured cheese. However, if the milk is pasteurized at too high a temperature, the proteins can be denatured, resulting in very soft curds that may not hold together.

The choice between raw and pasteurized milk ultimately depends on your personal preferences, the availability of milk sources, and your comfort level with the potential risks associated with raw milk.

Feta Cheese: Does It Get Moldy?

You may want to see also

Acidifying the milk

The first step in making cheese is to acidify the milk. Acidification helps separate the curds and whey and control the growth of undesirable bacteria. There are two main ways to acidify milk: direct acidification and using starter cultures.

Direct acidification involves adding an acid, such as vinegar, lemon juice, or citric acid, directly to the milk to achieve the correct acidity. This method is used for cheeses like ricotta, mascarpone, and queso fresco. The advantage of direct acidification is that it is a quicker process and does not require the addition of bacteria cultures.

The other way to acidify milk is by adding starter cultures of bacteria, which is called ripening. These bacteria convert the lactose in the milk into lactic acid, increasing the acidity. The type, quality, and safety of the cheese are defined by the specific starter culture used. Different starter cultures are chosen based on the desired flavour and their ability to withstand different temperatures. This method typically takes longer than direct acidification but allows for more complex flavours to develop.

Mesophilic and thermophilic cultures are the most commonly used starter cultures. Mesophilic bacteria thrive at moderate temperatures (around 86°F or room temperature) and are used for mellow cheeses like cheddar, gouda, and colby. Thermophilic bacteria thrive at higher temperatures (around 55°C) and are used for sharper cheeses such as Gruyère, Parmesan, and Romano.

The rate of acidification is crucial in cheesemaking. If the milk is acidified too quickly, the cheese can become grainy or brittle, while slow acidification can result in a sour taste. Measuring the pH and titratable acidity (TA) helps cheesemakers control the rate of acidification. pH measures the concentration of hydrogen ions, with lower pH values indicating higher acidity. TA is related to the amount of acid present, but it also measures the buffer capacity of the milk or whey.

Removing Grainy Texture: Perfecting the Cheese Sauce

You may want to see also

Cutting the curds

To cut the curds, you can use specialised tools such as a curd knife, a curd cutter, a whisk, or a ladle. A curd knife has a long, thin blade that is used for making precise vertical cuts. A curd cutter is a wire frame with multiple wires that create uniform cuts. A whisk is used for gentle stirring and breaking up curds in soft cheese recipes, and a ladle helps turn the curds and check their size during the cutting process. For home cheese-making, a long knife with a thin blade can be used, although investing in proper cheese-making tools can lead to more consistent results.

Before cutting the curds, it is important to let the rennet do its job and set the curd. Most recipes will then instruct you to cut the curd into smaller cubes or chunks. You can cut the curd by following these steps:

- Put your knife or palette at the edge of the pot, matching the required curd size.

- Cut through the curd from one side of the pot to the other, reaching the bottom of the pot.

- Move the knife across the same distance as the required curd size and repeat, creating equal lines across the curd.

- Turn the pot 90 degrees and repeat the above steps to create a checkerboard-like pattern.

- Place your knife at a 45-degree angle and cut at the same distance, keeping the knife angled.

- Turn the pot 90 degrees again and repeat the angled cuts to cover the remaining curd.

After cutting the curds, you may need to use a whisk to further reduce the curd size, especially for harder cheeses like Parmesan. It is important to gently move the whisk through the curds to slice them into smaller pieces without completely breaking them down.

Removing Brie Cheese Rind: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Draining the whey

To drain the whey, you will need to separate the curds from the whey. This can be done by cutting the curd into smaller cubes or chunks using a "cheese harp", a knife, or even a whisk. The smaller the curds, the drier and more ageable the cheese will be. You will then need to stir the curds in the vat for several minutes or even an hour, depending on the recipe. During this time, you may also apply heat and continue stirring to dry out the curds further.

Washing is another process used to remove whey from the vat. It involves removing some of the whey and replacing it with water. After draining the whey, it is important not to let it sit for too long, as the bacteria will continue to work on the lactose, and the whey will become more acidic.

Instead of discarding the whey, it can be used for various purposes. Whey contains vitamins, minerals (especially potassium), proteins, and beneficial bacteria. It can be fed to animals as a protein source, used as a substitute for buttermilk in recipes, added to the soaking water for beans, or used as a marinade for meat. It can also be used to lower the pH of garden soil, benefiting plants that prefer more acidic soil.

Unlocking the Cheese Domo: A Guide to Success

You may want to see also

Aging your cheese

Another important factor is the container in which the cheese is aged. For mold-ripened cheese, an enclosed container is best, placed in the cheese cave to maintain the proper temperature and humidity for optimal mold growth. The container should be sized so that there is approximately 40% cheese and 60% empty space. Cheese mats can also be used within the containers to keep the cheese slightly elevated, allowing it to breathe and preventing the bottom from becoming too moist.

The aging process can be affected by the initial size of the curds. Smaller curds will result in a drier and more ageable cheese. Additionally, stirring and cooking the curds will also impact the moisture content, with more stirring and cooking resulting in a drier cheese.

Aging cheese does not require a dedicated space, and there are creative ways to age cheese at home. An old ice chest, a back closet, or even a crisper drawer in a refrigerator can be used. With some creativity and the right conditions, you can successfully age your cheese and develop its flavor and complexity.

Cleaning Ovens: Removing Stubborn, Melted Cheese

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The ingredients you need to make cheese are milk, vinegar, and salt. The fresher the milk, the better your cheese will taste. You can use whole milk, skim milk, raw milk, or pasteurized milk.

You will need a large pot, a cheese harp or knife, a strainer, and cheesecloth. You can also use cutting boards and milk jugs filled with water to press your cheese into shape.

The first step is to heat your milk to around 195°F (90°C), stirring constantly to prevent scorching. Then, add an acidifier like vinegar or citric acid to get the correct acidity.

Once you have added the acidifier, stir the curds gently for about 10 minutes until they have formed and absorbed the acid. Then, collect the solid curds with a strainer and transfer them to cheesecloth to hang and drain the moisture, or leave them in the strainer over a bowl for at least 30 minutes.