The discovery of penicillin, the world's first antibiotic, is often associated with Alexander Fleming's famous observation in 1928, but a lesser-known yet intriguing connection exists between penicillin and cheese. Centuries before Fleming, ancient cultures, including the Egyptians and Greeks, noticed that certain molds could inhibit bacterial growth, a phenomenon occasionally observed in aged cheeses. These early observations laid the groundwork for understanding the antimicrobial properties of molds. In the context of cheese, the presence of *Penicillium* molds, which are used in the production of cheeses like Camembert and Brie, inadvertently demonstrated the mold's ability to prevent bacterial contamination. This historical interplay between cheese-making and natural mold inhibitors provided a precursor to Fleming's groundbreaking discovery, highlighting how traditional practices in food preservation inadvertently contributed to one of the most significant medical advancements in history.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Discovery Context | Penicillin was discovered by Sir Alexander Fleming in 1928. |

| Role of Cheese | A contaminated Petri dish with Staphylococcus bacteria was left open, allowing mold (Penicillium notatum) from a nearby lab to grow on it. The mold inhibited bacterial growth, resembling a cheese-like appearance. |

| Mold Species | Penicillium notatum (later identified as the source of penicillin). |

| Bacterial Inhibition | The mold produced a substance (penicillin) that killed or inhibited bacteria, notably Staphylococcus. |

| Accidental Discovery | Fleming’s discovery was serendipitous, as the dish was accidentally left uncovered. |

| Initial Observation | Fleming noticed a clear zone around the mold where bacteria could not grow, similar to mold on spoiled cheese. |

| Historical Significance | This discovery led to the development of the first antibiotic, revolutionizing medicine. |

| Cheese Connection | The mold’s appearance and growth pattern resembled mold on cheese, though the actual mold was not from cheese. |

| Further Development | Fleming’s findings were later advanced by scientists like Howard Florey and Ernst Chain, who purified and mass-produced penicillin. |

| Impact on Medicine | Penicillin became a life-saving treatment for bacterial infections, reducing mortality rates significantly. |

| Myth Clarification | The mold was not directly from cheese but from airborne Penicillium spores, though the appearance was cheese-like. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Alexander Fleming’s accidental discovery in 1928 while studying bacteria on petri dishes

- Mold contamination on Staphylococcus plates led to bacteria-free zones around mold

- Identification of Penicillium notatum as the mold producing the antibiotic substance

- Early challenges in isolating and purifying penicillin for medical use

- Role of cheese mold in inspiring Fleming’s research and discovery process

Alexander Fleming’s accidental discovery in 1928 while studying bacteria on petri dishes

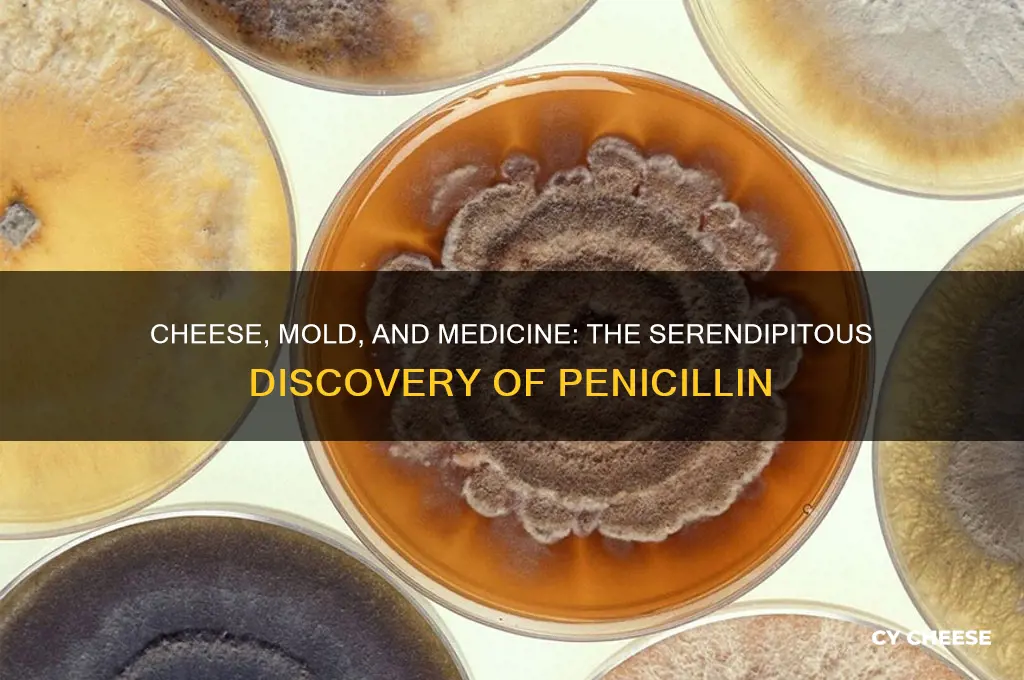

In 1928, Alexander Fleming’s laboratory was a chaotic mess, a detail often overlooked in the story of penicillin’s discovery. Fleming, a bacteriologist at St. Mary’s Hospital in London, had returned from a summer vacation to find his petri dishes contaminated with mold. Most scientists would have discarded them, but Fleming noticed something unusual: the mold, later identified as *Penicillium notatum*, had created a bacteria-free zone around itself. This accidental observation became the cornerstone of modern antibiotics. The connection to cheese? Molds like *Penicillium* are commonly used in cheese production, and Fleming’s discovery highlighted the antimicrobial properties of such molds, bridging the gap between food science and medicine.

To replicate Fleming’s discovery at home (for educational purposes only), start by sterilizing petri dishes and inoculating them with a harmless bacteria culture, such as *Staphylococcus* (available from educational suppliers). Introduce a small piece of *Penicillium*-based cheese (like Camembert) into one dish and observe over 7–10 days. You’ll likely see a clear zone around the mold, mimicking Fleming’s original finding. This experiment underscores the serendipity of scientific discovery and the unexpected links between everyday foods and life-saving medicines.

Fleming’s initial discovery was groundbreaking, but it was not immediately recognized as a medical breakthrough. He published his findings in 1929, noting the mold’s ability to inhibit bacterial growth, but lacked the resources to develop it further. It wasn’t until the 1940s that scientists like Howard Florey and Ernst Chain isolated and purified penicillin, turning it into a mass-produced antibiotic. This delay highlights the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration and the often-overlooked role of chance in scientific progress.

From a practical standpoint, penicillin’s discovery revolutionized medicine, saving millions of lives during World War II and beyond. Today, penicillin derivatives like amoxicillin are prescribed in dosages ranging from 250 mg to 1,000 mg, depending on the infection and patient age. However, overuse has led to antibiotic resistance, a cautionary tale stemming from Fleming’s accidental find. To combat this, always complete the full course of antibiotics as prescribed and avoid using them for viral infections like the common cold.

Finally, the story of penicillin serves as a reminder to embrace curiosity and observe the unexpected. Fleming’s cluttered lab and contaminated dishes could have been dismissed as failures, but his keen eye turned them into a discovery that changed the world. Whether in a laboratory or a kitchen, the interplay between food, science, and medicine continues to offer lessons in innovation and humility. So, the next time you see mold on cheese, remember: it might just hold the key to the next great discovery.

String Cheese vs. Shredded: Which Cheese Packs More Calories?

You may want to see also

Mold contamination on Staphylococcus plates led to bacteria-free zones around mold

The accidental contamination of Staphylococcus plates with mold in Alexander Fleming’s laboratory in 1928 revealed a striking phenomenon: bacteria-free zones emerged around the mold colonies. This observation, though seemingly minor, became the cornerstone of penicillin’s discovery. Fleming noted that the mold, later identified as *Penicillium notatum*, secreted a substance inhibiting bacterial growth. This serendipitous event highlighted the potential of mold-derived compounds as antibacterial agents, shifting the focus of medical research toward natural antimicrobials.

Analyzing this event, the bacteria-free zones demonstrated a clear antagonistic relationship between the mold and *Staphylococcus*. The mold’s secretion, now known as penicillin, disrupted bacterial cell wall synthesis, leading to bacterial lysis. This mechanism of action was revolutionary, as existing antibacterials at the time were either ineffective or highly toxic. Fleming’s meticulous documentation of the zones’ size and consistency provided early evidence of penicillin’s dose-dependent efficacy, laying the groundwork for future standardization of antibiotic dosages.

To replicate this observation in a controlled setting, one could inoculate agar plates with *Staphylococcus* and introduce *Penicillium* spores. Incubate at 25°C for 48–72 hours, observing the formation of clear zones around the mold. This simple experiment underscores the importance of aseptic technique, as contamination with other microorganisms could obscure results. For educational purposes, this activity is suitable for high school or undergraduate students, offering a tangible connection to the history of antibiotics.

Persuasively, the bacteria-free zones around the mold colonies serve as a reminder of the power of observation in scientific discovery. Fleming’s willingness to investigate an unintended outcome transformed a laboratory mishap into a medical breakthrough. Today, this principle encourages researchers to embrace unexpected findings, fostering innovation in fields beyond microbiology. Practical tip: when conducting similar experiments, maintain detailed records of environmental conditions (e.g., temperature, humidity) to ensure reproducibility.

Comparatively, while Fleming’s discovery was pivotal, it was the later work of Florey and Chain that scaled penicillin production and clinical application. The bacteria-free zones were the initial proof of concept, but translating this into a life-saving drug required interdisciplinary collaboration. This historical progression highlights the importance of bridging laboratory observations with practical solutions, a lesson applicable to modern drug development. For instance, current antibiotic research often begins with screening natural compounds, echoing Fleming’s approach.

Descriptively, the sight of bacteria-free zones on the Staphylococcus plates must have been both puzzling and exhilarating for Fleming. The contrast between the cloudy bacterial growth and the clear, mold-surrounded areas was a visual testament to nature’s ingenuity. This image, now iconic in scientific history, symbolizes the intersection of chance and curiosity. Practical takeaway: when working with microbial cultures, always inspect plates for unusual patterns—they might hold the key to the next breakthrough.

Exploring Cheese-Free Zones: Surprising Places Without This Dairy Staple

You may want to see also

Identification of Penicillium notatum as the mold producing the antibiotic substance

The discovery of penicillin as the first antibiotic began with a serendipitous observation: a mold contaminating a bacterial culture inhibited the growth of staphylococcus. This mold, later identified as *Penicillium notatum*, became the cornerstone of modern medicine. But how did scientists pinpoint this specific fungus as the source of the antibiotic substance? The process involved meticulous isolation, experimentation, and validation, transforming a chance finding into a life-saving breakthrough.

To identify *Penicillium notatum*, researchers first cultured the mold in controlled conditions, extracting its secretions to test against various bacteria. They observed that the mold’s filtrate consistently inhibited bacterial growth, particularly in staphylococci and streptococci. By comparing this activity to other molds, they confirmed that *Penicillium notatum* produced a unique, potent substance. This systematic approach ensured that the antibiotic effect was not due to contamination or other variables, laying the groundwork for further investigation.

One critical step was purifying the active compound, later named penicillin. Early attempts yielded small, unstable quantities, but by optimizing growth conditions—such as using nutrient-rich media like cheese whey—scientists increased production. Cheese, a common food item, inadvertently played a role in these experiments, as its whey provided an ideal substrate for the mold. This practical tip highlights how everyday materials can contribute to scientific discovery, though the focus remained on isolating the mold itself.

The identification of *Penicillium notatum* was not without challenges. Initial doses of penicillin were too low to treat systemic infections, and early clinical trials were limited by availability. For instance, the first patient treated with penicillin in 1941 received a dose of 160 mg, but the drug was not yet stable enough for widespread use. It wasn’t until large-scale fermentation techniques were developed that penicillin became a viable treatment, saving countless lives during World War II.

In conclusion, the identification of *Penicillium notatum* as the mold producing penicillin required scientific rigor, creativity, and persistence. From isolating the mold to purifying its antibiotic substance, each step built upon the last, turning a laboratory curiosity into a medical revolution. This process underscores the importance of observation, experimentation, and resourcefulness in scientific discovery, even when using something as ordinary as cheese whey.

Exploring the Cheese Topping Mystery on Fish Fillet Sandwiches

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Early challenges in isolating and purifying penicillin for medical use

The discovery of penicillin's antibacterial properties in moldy cheese marked a pivotal moment in medical history, but the journey from this observation to a usable drug was fraught with technical hurdles. One of the earliest challenges was the instability of penicillin itself. The compound degraded rapidly under normal conditions, making it difficult to extract and preserve in a form that retained its therapeutic efficacy. Researchers found that penicillin lost potency within days, even when refrigerated, which complicated efforts to study its effects and produce it in meaningful quantities. This instability required the development of specialized techniques to stabilize the compound, a task that demanded both chemical ingenuity and a deep understanding of penicillin's molecular structure.

Another significant obstacle was the difficulty of isolating penicillin from the mold in which it was produced. The mold, *Penicillium notatum*, secreted penicillin in minute quantities, and the compound was often contaminated with other substances from the mold's metabolism. Early attempts to purify penicillin involved crude filtration and extraction methods, which yielded inconsistent results. Scientists had to devise more sophisticated techniques, such as using organic solvents and chromatography, to separate penicillin from impurities. Even then, the process was labor-intensive and yielded only small amounts of the drug, insufficient for widespread clinical use.

Scaling up production posed yet another challenge. While laboratory-scale experiments showed promise, replicating the process on an industrial scale proved daunting. The mold required specific growth conditions, including precise temperature, humidity, and nutrient levels, which were difficult to maintain in large fermentation tanks. Contamination by other microorganisms was a constant threat, often ruining entire batches. Researchers had to develop sterile cultivation methods and optimize fermentation processes to ensure consistent penicillin production. This required significant investment in infrastructure and a trial-and-error approach that delayed mass production.

Finally, the challenge of delivering penicillin effectively to patients added another layer of complexity. Early formulations were unstable in solution, making intravenous administration problematic. Oral delivery was ineffective because penicillin was broken down by stomach acids before it could enter the bloodstream. Scientists had to develop methods to stabilize penicillin in injectable form, such as lyophilization (freeze-drying), which allowed the drug to be stored as a powder and reconstituted when needed. This innovation was crucial for making penicillin a practical treatment, but it required additional research and testing to ensure safety and efficacy.

In summary, the early challenges in isolating and purifying penicillin were multifaceted, involving issues of stability, extraction, scalability, and delivery. Overcoming these hurdles required a combination of scientific creativity, technical innovation, and perseverance. The lessons learned during this process laid the foundation for modern pharmaceutical production and underscored the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in translating scientific discoveries into life-saving treatments.

Exploring McDonald's Menu: Are Cheese Curds a Hidden Option?

You may want to see also

Role of cheese mold in inspiring Fleming’s research and discovery process

The discovery of penicillin, one of the most transformative medical breakthroughs of the 20th century, owes a surprising debt to cheese mold. In 1928, Alexander Fleming, a bacteriologist at St. Mary’s Hospital in London, returned to his lab after a summer break to find a Petri dish contaminated with a mold that had inhibited the growth of *Staphylococcus* bacteria. This mold, later identified as *Penicillium notatum*, produced a substance that killed bacteria—a phenomenon Fleming termed "penicillin." While the story often focuses on Fleming’s serendipitous observation, the connection to cheese mold is less widely discussed but equally intriguing. Cheese, a product of controlled mold fermentation, had long been a staple in human diets, yet its microbial byproducts were largely unexplored for medicinal purposes. Fleming’s familiarity with microbial cultures, including those found in cheese, likely primed his curiosity about the mold’s antibacterial properties.

Analyzing the role of cheese mold in Fleming’s discovery reveals a broader scientific context. Molds like *Penicillium* are common in aged cheeses such as Camembert and Roquefort, where they contribute to flavor and texture. These molds produce secondary metabolites, including antimicrobial compounds, to compete with bacteria in their environment. Fleming’s observation of *Penicillium* inhibiting bacterial growth mirrored the natural processes occurring in cheese production. While he did not directly experiment with cheese mold, his work was part of a larger scientific tradition of studying microbial interactions. For instance, earlier researchers like Ernest Duchesne had noted the antibacterial effects of molds in the late 19th century, though their findings were overlooked. Fleming’s breakthrough lay in recognizing the potential of *Penicillium*’s antibacterial properties and isolating penicillin as a therapeutic agent.

To understand the practical implications of cheese mold in Fleming’s research, consider the following steps: First, observe how molds in cheese create zones of inhibition against bacteria, similar to Fleming’s Petri dish. Second, experiment with culturing *Penicillium* from cheese to study its antimicrobial activity. For safety, use sterile techniques and handle molds in a controlled environment. Third, compare the efficacy of different cheese molds against common pathogens, such as *E. coli* or *Staphylococcus*. This hands-on approach not only replicates Fleming’s methodology but also highlights the untapped potential of everyday microbial processes. For educators or hobbyists, this exercise can be adapted for age groups 12 and up, using agar plates and cheese samples from local markets.

A persuasive argument for the significance of cheese mold in Fleming’s discovery lies in its historical and cultural context. Cheese-making, an ancient practice, had inadvertently provided humanity with a natural antibiotic long before modern medicine. Fleming’s work built on this foundation, translating a culinary phenomenon into a life-saving drug. Today, as antibiotic resistance threatens global health, revisiting the origins of penicillin reminds us of the value of interdisciplinary thinking. By studying microbial interactions in food, scientists can uncover new antimicrobial agents. For instance, researchers are exploring *Penicillium* strains from artisanal cheeses for novel antibiotics. This approach not only honors Fleming’s legacy but also addresses contemporary challenges.

In conclusion, the role of cheese mold in inspiring Fleming’s research underscores the interconnectedness of science, history, and everyday life. From the molds in a Petri dish to those in a wheel of cheese, the principles of microbial competition and cooperation remain consistent. Fleming’s discovery of penicillin was not just a stroke of luck but a product of curiosity, observation, and a deep understanding of microbial biology. By examining the link between cheese mold and penicillin, we gain insights into the origins of modern medicine and a roadmap for future discoveries. Whether in the lab or the kitchen, the humble mold continues to hold untapped potential, waiting to be explored.

Uncovering the Gaps: Understanding the 'Hole in the Cheese' in Healthcare

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Penicillin was discovered when Alexander Fleming noticed that a mold growing on a contaminated petri dish inhibited bacterial growth. While the story of cheese is often associated with this discovery, it’s a myth. The mold was actually *Penicillium notatum*, which grew on a staphylococci culture, not cheese.

No direct connection exists between cheese and penicillin’s discovery. The confusion likely stems from the fact that *Penicillium* molds are used in cheese production, but Fleming’s discovery involved a different strain of the mold growing on a bacterial culture, not cheese.

No, Fleming did not leave cheese out. The discovery occurred when he observed a mold contaminating a bacterial culture in his lab. The mold, *Penicillium notatum*, inhibited bacterial growth, leading to the development of penicillin as an antibiotic.

The association likely arises because *Penicillium* molds are used in cheese-making, such as in blue cheese. However, the specific mold in Fleming’s experiment was not from cheese but from a contaminated lab culture, making the cheese connection a popular misconception.