The question of whether all cheese is considered processed is a nuanced one, as the term processed can vary widely in its interpretation. While all cheese undergoes some level of processing—such as curdling milk, separating whey, and aging—not all cheeses are heavily altered or contain additives. For instance, traditional cheeses like cheddar or mozzarella are minimally processed, relying on natural fermentation and aging. In contrast, highly processed cheeses, such as American cheese singles or cheese spreads, often include emulsifiers, preservatives, and artificial ingredients to enhance texture, shelf life, or flavor. Thus, the degree of processing in cheese depends on the methods and ingredients used, making it essential to distinguish between minimally processed and heavily altered varieties.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition of Processed Cheese | Cheese made by combining one or more natural cheeses with emulsifying salts, additional dairy ingredients, and sometimes preservatives. |

| Is All Cheese Processed? | No. Not all cheese is processed. Natural or "unprocessed" cheese is made directly from milk, rennet, and bacterial cultures without additional additives or emulsifiers. |

| Examples of Processed Cheese | American cheese, cheese slices, cheese spreads, and some pre-shredded cheeses with anti-caking agents. |

| Examples of Unprocessed Cheese | Cheddar, mozzarella, gouda, brie, feta, and other cheeses made directly from milk without emulsifiers. |

| Processing Methods | Processed cheese involves melting, blending, and adding emulsifiers. Unprocessed cheese involves curdling milk, pressing, and aging. |

| Additives | Processed cheese often contains emulsifying salts (e.g., sodium phosphate), preservatives, and flavor enhancers. Unprocessed cheese typically has minimal or no additives. |

| Texture and Flavor | Processed cheese has a smooth, uniform texture and consistent flavor. Unprocessed cheese varies in texture and flavor based on type and aging. |

| Shelf Life | Processed cheese generally has a longer shelf life due to additives. Unprocessed cheese has a shorter shelf life and may require refrigeration. |

| Nutritional Differences | Processed cheese may have higher sodium and lower protein content compared to unprocessed cheese. |

| Labeling | Processed cheese is often labeled as "processed cheese," "cheese product," or "cheese food." Unprocessed cheese is labeled by its specific type (e.g., cheddar, mozzarella). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Natural vs. Processed Cheese

Cheese, in its most basic form, is a natural product made from milk through a process of curdling, draining, and aging. However, the term "processed cheese" has muddied the waters, leading many to question whether all cheese falls into this category. The distinction lies in the extent of human intervention and the additives involved. Natural cheese, such as cheddar or mozzarella, is crafted with minimal processing, relying on traditional methods to develop flavor and texture. Processed cheese, on the other hand, undergoes additional steps like melting, emulsifying, and blending with stabilizers, often resulting in a uniform, shelf-stable product. Understanding this difference is key to making informed choices about what you consume.

From a nutritional standpoint, natural cheese retains more of its original nutrients, including calcium, protein, and vitamins. For instance, a 30g serving of natural cheddar provides about 7g of protein and 200mg of calcium, with minimal additives. Processed cheese, while still a source of these nutrients, often contains higher levels of sodium, preservatives, and artificial flavors. A comparable serving of processed cheese can have up to 400mg of sodium, nearly double that of its natural counterpart. For individuals monitoring their sodium intake, such as those with hypertension, opting for natural cheese is a healthier choice. Always check labels for additives like sodium phosphate or sorbic acid, which are common in processed varieties.

The flavor and texture of natural cheese are inherently tied to its aging process and the specific bacteria or molds used. For example, a 12-month aged Parmesan develops a sharp, nutty flavor, while a young Gouda remains mild and creamy. Processed cheese, however, is engineered for consistency, often lacking the complexity of natural varieties. This makes natural cheese ideal for culinary applications where depth of flavor is desired, such as grating over pasta or pairing with wine. Processed cheese, with its meltability and uniformity, is better suited for sandwiches or sauces. Choosing between the two depends on the intended use and your flavor preferences.

For those looking to incorporate more natural cheese into their diet, start by reading labels carefully. Look for terms like "100% natural cheese" or "artisanal," which indicate minimal processing. Avoid products labeled as "cheese food" or "cheese product," as these are typically highly processed. Experiment with different types of natural cheese to discover new flavors and textures. For example, swap processed American cheese slices with natural Swiss or provolone in sandwiches. When cooking, opt for natural cheddar or Gruyère for richer, more authentic results in dishes like macaroni and cheese or grilled cheese sandwiches. Small changes like these can elevate both the nutritional value and taste of your meals.

In conclusion, while all cheese undergoes some level of processing, the degree and nature of that processing define the difference between natural and processed varieties. Natural cheese offers superior nutritional benefits, richer flavors, and greater culinary versatility, making it the preferred choice for health-conscious consumers and food enthusiasts alike. By understanding these distinctions and making informed choices, you can enjoy cheese in its most wholesome form while still indulging in the occasional convenience of processed options.

Discover the Classic Steak and Cheese Hot Sandwich: A Delicious Guide

You may want to see also

Cheese-Making Techniques Explained

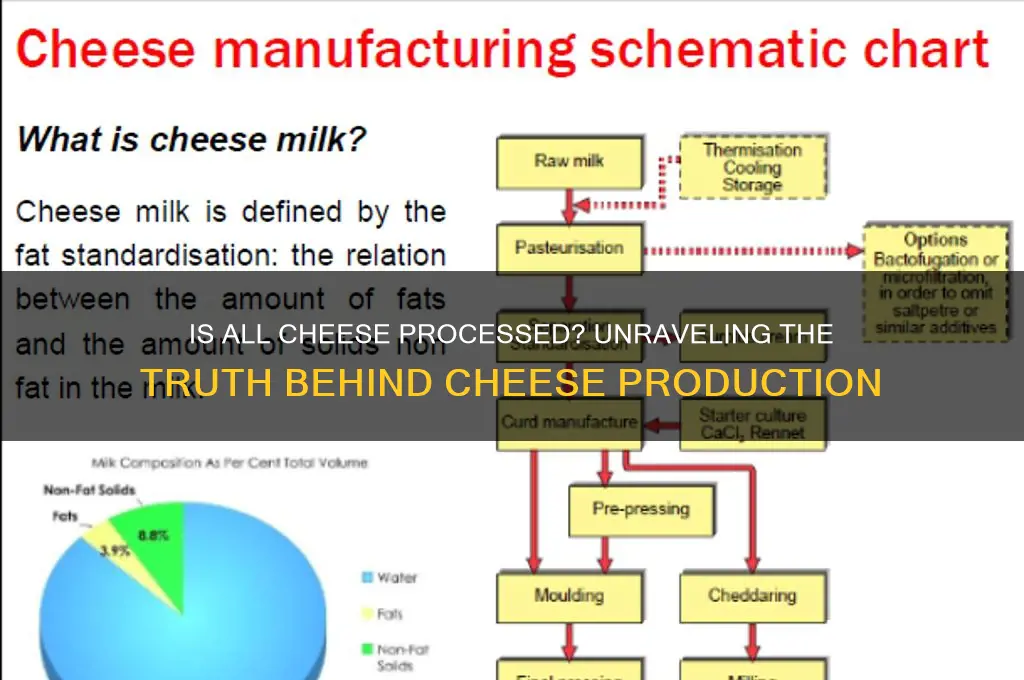

Not all cheese is considered processed, but understanding cheese-making techniques reveals why some cheeses fall into this category while others remain closer to their natural state. At its core, cheese-making involves curdling milk, separating curds from whey, and aging the product. However, the methods and additives used during these steps determine whether a cheese is minimally processed or highly manipulated. For instance, traditional cheeses like cheddar or mozzarella rely on simple ingredients—milk, rennet, and salt—and natural aging processes. In contrast, processed cheeses, such as American cheese slices, undergo melting, blending with emulsifiers, and pasteurization to extend shelf life and achieve uniformity.

Consider the role of heat in cheese-making, a critical factor in distinguishing processed from natural cheeses. Hard cheeses like Parmesan are heated to high temperatures (around 55°C or 131°F) during production, which expels moisture and concentrates flavor. While this is a traditional technique, it does not classify the cheese as processed. Processed cheeses, however, are heated to even higher temperatures (often above 70°C or 158°F) and combined with stabilizers like sodium phosphate to create a smooth, meltable texture. This industrial approach prioritizes convenience and consistency over artisanal craftsmanship, blurring the line between natural and processed.

Aging is another technique that separates the cheese spectrum. Artisanal cheeses are aged for weeks, months, or even years, allowing natural bacteria and molds to develop complex flavors. For example, a wheel of Gruyère matures for a minimum of 5 months, during which its rind hardens and its interior becomes nutty and slightly sweet. Processed cheeses bypass this time-consuming step by using artificial flavorings and preservatives to mimic aged profiles. While this reduces production costs and increases accessibility, it sacrifices the depth and authenticity of traditionally aged cheeses.

For home cheese-makers, understanding these techniques can empower experimentation. Start with simple recipes like ricotta, which requires only milk, vinegar or lemon juice, and gentle heat. Heat 1 gallon of whole milk to 180°F (82°C), stir in 3 tablespoons of vinegar, and let the curds form for 10 minutes before straining. This minimally processed approach yields fresh, creamy cheese in under an hour. For those seeking a challenge, try making mozzarella, which involves stretching the curds in hot water (170°F or 77°C) until glossy and elastic—a hands-on technique that highlights the artistry of cheese-making.

In conclusion, while all cheese undergoes some level of processing, the techniques used determine its classification. Traditional methods prioritize natural ingredients and time-honored practices, resulting in cheeses that are minimally processed. Industrial techniques, on the other hand, rely on heat, additives, and shortcuts to create uniform, shelf-stable products. By understanding these distinctions, consumers and cheese-makers alike can make informed choices about the cheeses they enjoy or create, appreciating the craftsmanship behind each bite.

Mastering the Art of Cutting Wax-Wrapped Cheese: Tips and Tricks

You may want to see also

Additives in Cheese Production

Cheese production often involves additives, but their role varies significantly across types and processes. While some cheeses rely solely on milk, salt, and microbial cultures, others incorporate substances like enzymes, preservatives, or emulsifiers to enhance texture, extend shelf life, or standardize flavor. Understanding these additives clarifies why not all cheese is equally "processed" and helps consumers make informed choices.

Consider the enzyme rennet, commonly used to coagulate milk during cheesemaking. Traditional animal-derived rennet transforms milk into curds and whey, a step essential for hard cheeses like Parmesan. However, microbial or genetically modified rennet alternatives are increasingly used in mass production. While both achieve the same goal, the latter often reduces costs and accommodates dietary restrictions (e.g., vegetarian diets). Dosage typically ranges from 0.02% to 0.05% of milk weight, depending on the type of rennet and desired curd firmness. This example illustrates how additives can be both functional and divisive, depending on their origin and application.

Preservatives like natamycin (a natural antifungal) are another common additive, particularly in shredded or sliced cheeses. Applied at concentrations up to 20 ppm (parts per million), natamycin prevents mold growth without altering flavor or texture. While effective, its presence highlights the tension between convenience and minimal processing. Artisanal cheeses rarely use such additives, relying instead on natural aging and packaging methods. Consumers prioritizing "unprocessed" cheese should seek products labeled "no preservatives" or opt for whole, aged varieties where surface mold is part of the tradition, not a defect.

Emulsifiers like carrageenan or citric acid are occasionally added to processed cheese products to improve meltability or prevent separation. These additives are more common in cheese slices or spreads, where uniformity is prioritized over complexity. For instance, citric acid, used in concentrations up to 3%, accelerates curdling in fast-production cheeses like mozzarella. While these additives serve a purpose, they often signal a departure from traditional methods. Home cooks can avoid them by choosing block cheeses or experimenting with DIY melting techniques, such as adding a pinch of cornstarch (1 teaspoon per cup of shredded cheese) to achieve a smooth texture without commercial additives.

In summary, additives in cheese production are tools, not inherently good or bad. Their use depends on the cheese type, scale of production, and consumer expectations. By understanding specific additives—their functions, dosages, and alternatives—shoppers can differentiate between minimally processed artisanal cheeses and highly engineered products. The key takeaway? Not all cheese is equally processed, and additives are a measurable, actionable way to tell the difference.

Dairy-Free Cheese Options: Exploring Non-Dairy Alternatives Without Proteins

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Aging and Fermentation Process

Cheese, in its myriad forms, owes much of its complexity to the aging and fermentation processes. These techniques are not merely steps in production but are transformative journeys that dictate texture, flavor, and character. While all cheese undergoes some degree of processing, the extent and nature of aging and fermentation distinguish artisanal varieties from their mass-produced counterparts. Understanding these processes reveals why not all cheese should be lumped into the "processed" category.

Aging, or ripening, is a deliberate waiting game where cheese evolves under controlled conditions. During this phase, enzymes break down proteins and fats, intensifying flavors and altering textures. For instance, a young cheddar is mild and pliable, but after 12 to 24 months, it becomes sharp and crumbly. Similarly, Parmigiano-Reggiano ages for a minimum of 12 months, developing its signature granular texture and umami-rich profile. The duration and environment—humidity, temperature, and airflow—are critical. A slight deviation can lead to mold growth or dryness, underscoring the precision required in this craft.

Fermentation, the other cornerstone, is a microbial symphony. Lactic acid bacteria convert lactose into lactic acid, lowering pH and creating an environment hostile to harmful bacteria. This step is essential for preservation and flavor development. In blue cheeses like Roquefort, Penicillium molds introduced during production create veins of pungent flavor. Similarly, surface-ripened cheeses like Brie rely on molds such as Penicillium camemberti to form their bloomy rind and creamy interior. These microbial cultures are not additives but living participants in the cheese’s evolution, a stark contrast to the artificial preservatives in highly processed foods.

The interplay between aging and fermentation highlights the natural, time-honored methods that define traditional cheesemaking. Unlike processed cheese, which often contains emulsifiers, stabilizers, and artificial flavors, aged and fermented cheeses derive their qualities from biological processes. For example, the eyes in Swiss cheese result from carbon dioxide produced by Propionibacterium freudenreichii, not from mechanical intervention. This distinction is crucial for consumers seeking minimally altered, nutrient-dense foods.

Practical considerations abound for those appreciating or crafting aged cheeses. Home enthusiasts can experiment with aging by maintaining a consistent environment—a wine fridge set between 50°F and 55°F with 80-90% humidity is ideal. Regularly flipping and brushing the cheese prevents unwanted mold while allowing beneficial microbes to flourish. For fermentation, using high-quality starter cultures ensures predictable results. Pairing aged cheeses with complementary flavors—such as honey with aged Gouda or pears with sharp cheddar—enhances their complexity, turning a simple snack into a sensory experience.

In essence, the aging and fermentation processes elevate cheese from a basic dairy product to a nuanced culinary art. These methods, rooted in tradition and science, differentiate artisanal cheeses from their processed counterparts. By understanding and appreciating these transformations, consumers can make informed choices, savoring the depth and diversity that only time and microbes can impart.

Does Cheese Cause Nightmares? Unraveling the Myth Behind Dairy Dreams

You may want to see also

Defining Processed in Cheese Terms

Cheese, in its most basic form, is the result of curdled milk, yet the journey from milk to cheese involves a series of steps that can vary widely. This raises the question: at what point does cheese become "processed"? Understanding this requires a closer look at the methods and additives that transform raw ingredients into the final product. For instance, traditional cheeses like cheddar or mozzarella undergo minimal processing, primarily involving pasteurization, culturing, and aging. In contrast, processed cheese products, such as American cheese slices, often include emulsifiers, stabilizers, and artificial preservatives to enhance shelf life and texture.

Analyzing the term "processed" in cheese terms reveals a spectrum rather than a binary category. On one end are artisanal cheeses, where processing is limited to natural fermentation and aging. On the other end are highly engineered cheese products, where mechanical processes and chemical additives dominate. The key distinction lies in the purpose of the processing: is it to preserve the integrity of the cheese or to alter it for convenience and longevity? For example, pasteurization is a processing step, but it serves to eliminate harmful bacteria while retaining the cheese’s essential character. Conversely, the addition of sodium phosphate in processed cheese food is purely functional, aimed at improving meltability and texture.

To navigate this spectrum, consumers should focus on ingredient labels and production methods. A practical tip is to look for cheeses with short ingredient lists—ideally, just milk, salt, cultures, and enzymes. These are minimally processed and closer to their natural state. For those concerned about additives, avoiding terms like "cheese product," "cheese food," or "cheese spread" can help steer clear of highly processed options. Additionally, certifications such as "raw milk cheese" or "farmhouse cheese" often indicate traditional, low-intervention methods.

Comparatively, the health implications of processed versus minimally processed cheese are worth considering. While all cheese is nutrient-dense, providing protein, calcium, and vitamins, highly processed varieties often contain higher levels of sodium and artificial additives. For instance, a single slice of processed American cheese can contain up to 400 mg of sodium, compared to 170 mg in a similar portion of natural cheddar. This makes minimally processed cheeses a better choice for those monitoring sodium intake or seeking a more wholesome option.

In conclusion, defining "processed" in cheese terms is less about drawing a hard line and more about understanding the degree and purpose of intervention. By examining production methods and ingredient lists, consumers can make informed choices that align with their preferences for taste, health, and authenticity. Whether opting for a handcrafted cheddar or a convenient cheese slice, awareness of these distinctions empowers individuals to appreciate cheese in all its varied forms.

Master the Art of Freezing Cheese Slices for Longevity

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all cheese is considered processed. While some cheeses undergo minimal processing, others are highly processed with additives and preservatives.

Cheese is considered processed if it has been altered through methods like pasteurization, melting, or the addition of emulsifiers, stabilizers, or artificial ingredients.

Natural cheeses like cheddar and mozzarella undergo minimal processing, primarily involving pasteurization and culturing, so they are not typically classified as highly processed.

Highly processed cheeses include American cheese singles, cheese spreads, and canned cheese products, which often contain additives and are altered for texture and shelf life.

Processed cheese can still provide protein and calcium, but it often contains higher levels of sodium, fats, and artificial ingredients compared to natural cheeses.