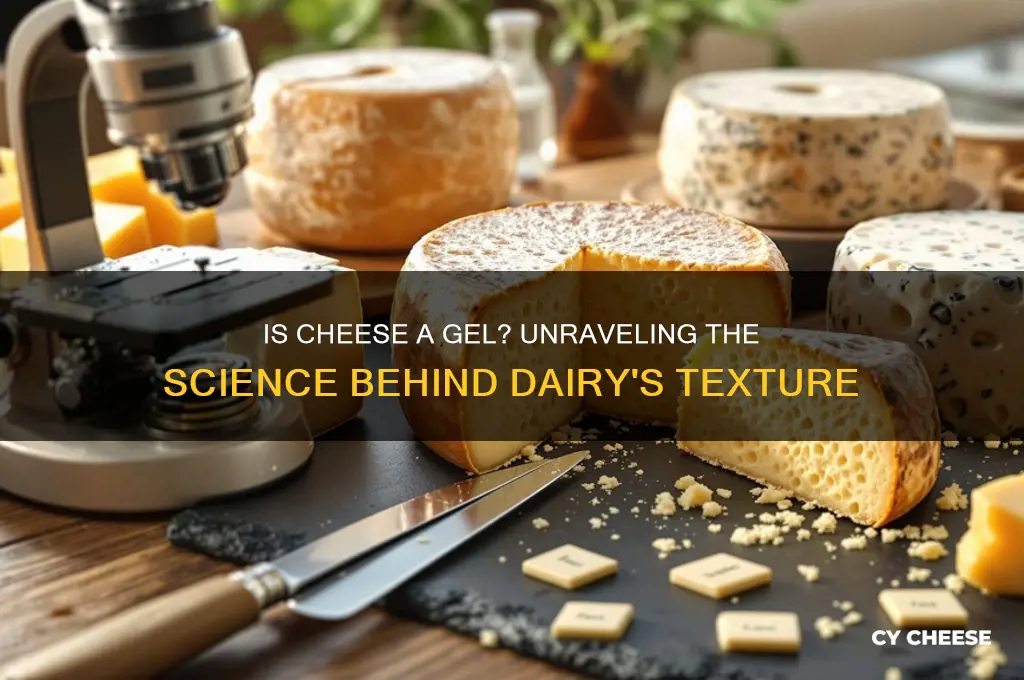

Cheese is often considered a solid food, but its unique texture and structure have sparked debates about its classification. One intriguing question that arises is whether cheese can be categorized as a gel. Gels are semi-solid systems consisting of a network of particles or molecules that trap liquid, and cheese shares some similarities with this definition. It is composed of a protein matrix, primarily casein, which forms a network that holds moisture, fat, and other components, resembling the structure of a gel. This perspective challenges the traditional view of cheese and opens up an interesting discussion on the science behind its composition and texture.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition of Gel | A gel is a semi-solid material that consists of a network of polymer chains or colloidal particles dispersed in a liquid medium. |

| Cheese Composition | Cheese is primarily composed of milk proteins (casein and whey), fat, water, and microorganisms. |

| Structure of Cheese | Cheese has a complex, porous structure formed by the coagulation of milk proteins and the expulsion of whey during the cheesemaking process. |

| Texture of Cheese | Cheese exhibits a range of textures, from soft and creamy to hard and crumbly, depending on the type and aging process. |

| Water Content in Cheese | Cheese typically contains 30-60% water, which is lower than the water content in most gels. |

| Network Formation in Cheese | The protein network in cheese is formed by the coagulation of casein micelles, which is different from the polymer or colloidal networks in traditional gels. |

| Rheological Properties | Cheese behaves more like a viscoelastic solid than a gel, with distinct yield stress and strain-hardening properties. |

| Classification of Cheese | While cheese shares some characteristics with gels, it is generally classified as a separate type of material due to its unique structure and composition. |

| Scientific Consensus | Most food scientists and rheologists do not classify cheese as a gel, although it exhibits gel-like properties in certain aspects. |

| Similarities to Gels | Cheese shares similarities with gels in terms of its semi-solid nature, water-holding capacity, and network structure. |

| Differences from Gels | Cheese differs from gels in its composition, network formation, and rheological behavior, which are more characteristic of a viscoelastic solid. |

Explore related products

$1.74

$1.74

What You'll Learn

- Definition of Gel: Is cheese classified as a gel based on its structure and properties

- Cheese Texture Analysis: How does cheese's texture compare to typical gel characteristics

- Protein Matrix Role: Does cheese's protein matrix qualify it as a gel

- Syneresis in Cheese: How does moisture expulsion in cheese relate to gel behavior

- Scientific Classification: What scientific criteria determine if cheese is a gel

Definition of Gel: Is cheese classified as a gel based on its structure and properties?

A gel is defined as a semi-solid system consisting of a network of polymer chains that span the volume of a liquid, giving it a finite, non-zero yield stress. This network traps the liquid, creating a material that behaves like a solid under low stress but can flow under higher stress. Cheese, with its complex structure of proteins and fats, often raises questions about its classification. To determine if cheese fits this definition, we must examine its microstructure and rheological properties.

Analyzing the structure of cheese reveals a matrix primarily composed of casein proteins and fat globules dispersed in a serum phase. During the cheesemaking process, enzymes and acids cause casein proteins to aggregate, forming a network that traps moisture, fat, and other components. This network resembles the polymeric structure of a gel, but the key distinction lies in the nature of the network and its ability to retain liquid under stress. For instance, a true gel, like gelatin, maintains its shape due to a continuous network of cross-linked polymers, whereas cheese’s structure is more heterogeneous and less uniform.

From a rheological perspective, cheese exhibits viscoelastic behavior, meaning it has both solid-like (elastic) and liquid-like (viscous) properties. However, not all cheeses behave the same way. Hard cheeses, such as cheddar, have a more rigid structure and higher yield stress, while soft cheeses, like Brie, have a lower yield stress and flow more easily. This variability complicates their classification as gels, as the definition of a gel requires a consistent network structure and yield stress across the material.

To classify cheese as a gel, one must consider practical implications. For example, in food science, understanding whether cheese behaves like a gel can influence processing techniques, such as cutting, melting, or packaging. If cheese were definitively a gel, manufacturers could apply gel-specific models to predict its behavior under different conditions. However, the lack of uniformity in cheese’s structure and properties suggests it may not fit neatly into the gel category, despite sharing some characteristics.

In conclusion, while cheese shares certain structural and rheological features with gels, its classification as a gel remains ambiguous. Its heterogeneous network and variable yield stress differentiate it from classical gels like gelatin or agar. For practical purposes, treating cheese as a unique material with gel-like properties may be more accurate, allowing for tailored approaches in both culinary and industrial applications.

Can Cheese Absorb Alcohol? Exploring the Myth and Science Behind It

You may want to see also

Cheese Texture Analysis: How does cheese's texture compare to typical gel characteristics?

Cheese, with its diverse textures ranging from creamy Brie to crumbly feta, challenges the conventional definition of a gel. Gels are typically characterized by a three-dimensional network that traps liquid, resulting in a semi-solid structure. While cheese shares some textural similarities with gels, such as firmness and elasticity, its composition and formation process set it apart. For instance, cheese is primarily a coagulated protein matrix (casein) interspersed with fat and moisture, whereas gels often rely on cross-linked polymers like gelatin or agar. This fundamental difference raises the question: can cheese truly be classified as a gel, or does it occupy a unique textural category of its own?

Analyzing cheese texture requires a systematic approach, often employing tools like texture profile analysis (TPA) or rheology. TPA measures attributes such as hardness, cohesiveness, and chewiness, which can be compared to gel characteristics. For example, a semi-soft cheese like mozzarella exhibits extensibility and elasticity akin to a weak gel, while a hard cheese like Parmesan lacks the fluid retention typical of gels. Rheological studies further reveal that cheese behaves more like a viscoelastic solid under stress, deforming in ways that gels, with their more uniform networks, do not. These methods highlight the complexity of cheese texture, suggesting it straddles the line between gel-like and non-gel-like properties.

From a practical standpoint, understanding cheese texture is crucial for culinary applications and product development. For instance, melting behavior, a key attribute in dishes like grilled cheese or fondue, depends on the cheese’s protein and fat distribution, not on gel-like properties. Chefs and food scientists can manipulate texture by adjusting factors such as pH, salt concentration, and aging time. For example, increasing salt content can firm up a cheese’s structure, while longer aging reduces moisture, resulting in a harder texture. These techniques underscore the importance of treating cheese as a distinct material, rather than forcing it into the gel framework.

Comparatively, while both gels and cheese exhibit structure-dependent textures, their formation mechanisms diverge significantly. Gels form through physical or chemical cross-linking of polymers, often in the presence of water. Cheese, however, relies on enzymatic coagulation of milk proteins, followed by syneresis (expulsion of whey) and aging. This process creates a heterogeneous matrix that resists simple categorization. For instance, cottage cheese’s granular texture arises from partially coalesced curds, a structure far removed from the uniform networks of gels. Such distinctions emphasize the need for a nuanced approach when discussing cheese texture in relation to gels.

In conclusion, while cheese shares some textural qualities with gels, its unique composition and formation process render it a distinct material. Texture analysis reveals both similarities and disparities, offering insights for culinary and industrial applications. Rather than labeling cheese as a gel, it is more productive to appreciate its complexity as a category unto itself, shaped by the interplay of proteins, fats, and moisture. This perspective not only enriches our understanding of cheese but also guides innovation in texture manipulation and product design.

Does Cheese Curdle in the Fridge? Facts and Storage Tips

You may want to see also

Protein Matrix Role: Does cheese's protein matrix qualify it as a gel?

Cheese, a dairy product beloved worldwide, owes its unique texture and structure to its protein matrix, primarily composed of casein proteins. This matrix forms a three-dimensional network that traps moisture, fat, and other components, giving cheese its characteristic firmness and elasticity. But does this protein matrix qualify cheese as a gel? To answer this, we must first understand what defines a gel. Gels are semi-solid systems where a liquid is immobilized within a network of polymers, often proteins or polysaccharides. This definition raises the question: is the protein matrix in cheese sufficiently structured to meet the criteria of a gel?

Analyzing the protein matrix in cheese reveals striking similarities to traditional gels. During cheese-making, rennet or acid coagulates milk, causing casein proteins to aggregate and form a continuous network. This network retains whey, the liquid portion of milk, within its interstices, much like how a gel traps solvent. For instance, in hard cheeses like cheddar, the protein matrix is tightly packed, resulting in a firm texture, while in soft cheeses like Brie, the matrix is more open, yielding a creamy consistency. These variations in matrix density and structure mirror the diversity seen in gels, from stiff pectin gels in jams to soft agarose gels in laboratories.

However, the classification of cheese as a gel is not without debate. One argument against this categorization is the dynamic nature of cheese’s protein matrix. Unlike many gels, which are formed through irreversible cross-linking, the casein network in cheese can undergo further changes during aging. Proteolytic enzymes break down casein proteins, altering the matrix structure and texture over time. This ongoing transformation challenges the static definition of a gel, which typically implies a stable, unchanging network. Yet, this very dynamism could be seen as an advanced feature of cheese as a gel, showcasing its ability to evolve while maintaining structural integrity.

To determine whether cheese’s protein matrix qualifies it as a gel, consider practical examples. In food science, gels are often evaluated based on their ability to retain liquid and resist deformation. Cheese excels in both aspects. For instance, a slice of mozzarella can stretch without breaking, demonstrating the elasticity of its protein matrix. Similarly, the ability of cheese to hold its shape when cut or melted reflects the strength of its gel-like structure. These properties are not merely theoretical but have real-world applications, such as in cooking, where cheese’s meltability and texture are crucial for dishes like grilled cheese sandwiches or pizza.

In conclusion, while the protein matrix in cheese shares many characteristics with gels, its classification is nuanced. The casein network’s ability to trap liquid, provide structure, and exhibit gel-like properties strongly supports the argument that cheese is indeed a gel. However, its dynamic nature during aging introduces complexity, setting it apart from traditional, static gels. Ultimately, whether cheese is a gel may depend on the context—in food science, its gel-like behavior is undeniable, but in stricter material science terms, its evolving structure might blur the lines. Regardless, the protein matrix in cheese remains a fascinating example of nature’s ingenuity, blending stability and adaptability in a single, delicious product.

Mastering Blazing Bull: Easy Cheese Strategies for Quick Victory

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$1.67

$1.74

Syneresis in Cheese: How does moisture expulsion in cheese relate to gel behavior?

Cheese, often debated as a gel, exhibits a phenomenon known as syneresis, where moisture is expelled from its matrix. This process is crucial in understanding the structural integrity and texture of cheese, as it directly relates to the behavior of gels under stress. Syneresis in cheese occurs when the protein network, primarily composed of casein, contracts and releases whey, the liquid component. This moisture expulsion is not merely a byproduct of aging but a key factor in determining the cheese’s firmness, shelf life, and sensory qualities. For instance, a well-controlled syneresis process in cheddar results in a smooth, sliceable texture, while excessive syneresis can lead to an unappealingly dry or crumbly product.

Analyzing syneresis through the lens of gel behavior reveals parallels between cheese and traditional gels like gelatin or agar. Both systems rely on a three-dimensional network to trap liquid, but cheese’s protein matrix is more complex and dynamic. In gels, syneresis is often triggered by mechanical stress or temperature changes, causing the network to shrink and release liquid. Similarly, in cheese, factors such as pH shifts during aging, salt concentration, and mechanical pressing during production induce syneresis. However, cheese’s unique composition—with fat globules and microbial cultures—adds layers of complexity. For example, in mozzarella, syneresis must be carefully managed to maintain its stretchability, achieved by controlling the heating and stretching process during production.

To mitigate unwanted syneresis in cheese, producers employ specific techniques. For hard cheeses like Parmesan, slow aging and low moisture content are intentional, enhancing flavor concentration. In contrast, soft cheeses like Brie require higher moisture levels, achieved by minimizing mechanical stress during production. Practical tips include maintaining consistent temperature and humidity during aging, as fluctuations can accelerate syneresis. For home cheesemakers, using a cheese press with precise pressure settings (e.g., 10–20 psi for cheddar) and monitoring pH levels (targeting 5.2–5.6 for optimal curd formation) can help control moisture expulsion.

Comparatively, syneresis in cheese differs from that in other dairy gels like yogurt, where the process is often undesirable and leads to whey separation. In cheese, syneresis is a deliberate step, shaping the final product’s texture and functionality. For instance, the controlled syneresis in Swiss cheese creates its characteristic eyes, formed by carbon dioxide gas released during bacterial fermentation. This contrasts with yogurt, where syneresis is typically prevented by stabilizers like pectin or starch. Understanding these distinctions highlights cheese’s unique position as a gel-like material where syneresis is both a challenge and a tool.

In conclusion, syneresis in cheese is a critical aspect of its gel-like behavior, influencing texture, moisture content, and overall quality. By studying this process, producers can manipulate cheese’s structure to achieve desired characteristics, whether it’s the creamy mouthfeel of Camembert or the crumbly texture of feta. For enthusiasts and professionals alike, mastering syneresis offers a deeper appreciation of cheese’s complexity and the science behind its transformation from milk to a beloved food product.

Refrigerate or Not? Storing Homemade Cheese Crackers Safely

You may want to see also

Scientific Classification: What scientific criteria determine if cheese is a gel?

Cheese, a beloved food across cultures, often sparks curiosity about its classification. To determine if cheese is a gel, we must examine the scientific criteria that define gels. Gels are semi-solid systems consisting of a network of particles or molecules trapping liquid within. This network gives gels their characteristic structure and texture. Cheese, with its solid yet yielding nature, shares some properties with gels but requires a deeper analysis to fit this classification.

From a structural perspective, cheese is composed of a protein matrix, primarily casein, which forms a network during the coagulation process. This network traps fat, moisture, and other components, creating the cheese’s texture. Gels, similarly, rely on a cross-linked polymer network to immobilize liquid. The key distinction lies in the nature of the network: gels typically involve chemical or physical cross-linking of polymers, whereas cheese’s structure is primarily driven by protein aggregation and fat distribution. For instance, a gel like gelatin forms through the hydrogen bonding of collagen strands, a process distinct from cheese-making.

To scientifically classify cheese as a gel, we must consider rheological properties—how materials flow and deform under stress. Gels exhibit viscoelastic behavior, meaning they have both elastic (solid-like) and viscous (liquid-like) properties. Cheese also demonstrates viscoelasticity, particularly in softer varieties like Brie or mozzarella. However, harder cheeses like Parmesan behave more like solids, deviating from the typical gel profile. Measuring these properties using techniques like dynamic mechanical analysis can provide quantitative data to assess if cheese meets gel criteria.

Another criterion is the role of water in the structure. In gels, water is entrapped within the polymer network, contributing to the material’s stability and texture. Cheese contains significant moisture, but its distribution and binding differ. For example, in fresh cheeses like ricotta, water is loosely held, while in aged cheeses, moisture is more tightly bound within the protein matrix. This variation complicates a blanket classification of cheese as a gel, as the water’s role is not uniform across types.

Practically, understanding whether cheese is a gel has implications for food science and culinary applications. If cheese were definitively classified as a gel, it could guide innovations in texture modification or preservation techniques. For instance, controlling the gelation process in cheese-making could lead to new textures or extended shelf life. However, the unique composition and formation of cheese suggest it occupies a distinct category, blending gel-like properties with characteristics of solids and emulsions. Thus, while cheese shares features with gels, its classification remains nuanced, reflecting its complex structure and origins.

The Art of Smoking Cheese: Techniques, Flavors, and Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, cheese is classified as a gel because it consists of a network of proteins (casein) and fats that trap water, forming a semi-solid structure characteristic of gels.

Cheese is a gel because its structure is a cross-linked network of proteins and fats that hold liquid, giving it a semi-solid, sliceable texture rather than being fully solid or liquid.

Yes, all types of cheese are gels, though their texture can vary. Hard cheeses like cheddar have a firmer gel structure, while soft cheeses like brie have a looser, more spreadable gel.