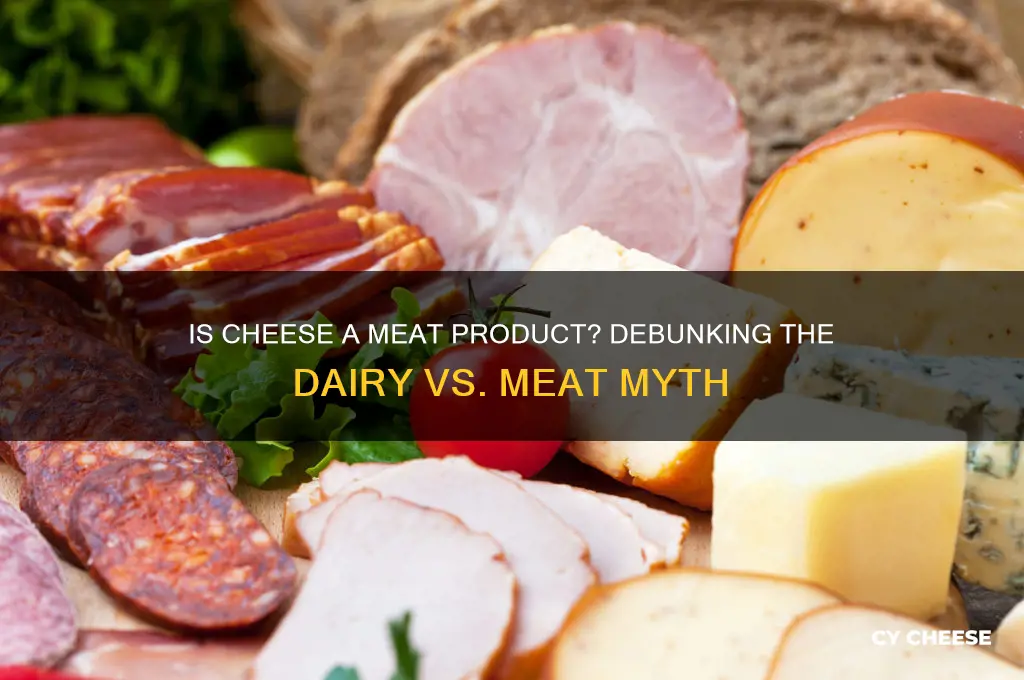

The question of whether cheese is a meat product often arises from confusion about its origins and composition. Cheese is, in fact, a dairy product made from milk, typically from cows, goats, or sheep, through a process of curdling and draining. It contains no meat or animal tissue, making it distinct from meat products, which are derived from the muscle, fat, or organs of animals. While cheese is a byproduct of animal agriculture, it falls into the category of dairy rather than meat, and its production does not involve the slaughter of animals for their flesh. This distinction is important for dietary, cultural, and ethical considerations, as many people choose to avoid meat for various reasons but may still consume dairy products like cheese.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Source Material | Cheese is made from milk, typically from cows, goats, or sheep. |

| Definition of Meat | Meat is defined as the flesh of animals used as food, excluding dairy products. |

| Protein Source | Cheese is a dairy product and not derived from animal flesh. |

| Nutritional Composition | Cheese contains protein, fat, and calcium, but lacks the muscle tissue found in meat. |

| Dietary Classification | Cheese is considered a dairy product, not a meat product, in dietary guidelines. |

| Production Process | Cheese is produced through curdling and fermenting milk, not through slaughtering animals for flesh. |

| Culinary Usage | Cheese is used as a dairy ingredient, distinct from meat in recipes and dishes. |

| Allergens/Restrictions | Cheese is not a meat product and is suitable for vegetarians (unless specified otherwise). |

| Regulatory Classification | Food safety and labeling regulations classify cheese as a dairy product, not meat. |

| Cultural Perception | Culturally, cheese is universally recognized as a dairy item, separate from meat products. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Cheese Ingredients: Cheese is made from milk, not meat, using bacteria and enzymes

- Dietary Classification: Cheese is dairy, not meat, and is vegetarian-friendly in most cases

- Production Process: Rennet, often animal-derived, is used but doesn’t classify cheese as meat

- Nutritional Comparison: Cheese lacks meat’s protein and iron but contains calcium and fat

- Cultural Perception: Some cultures view cheese as non-meat, while others debate its status

Cheese Ingredients: Cheese is made from milk, not meat, using bacteria and enzymes

Cheese, a staple in diets worldwide, is fundamentally a dairy product, not a meat product. Its primary ingredient is milk, derived from animals such as cows, goats, or sheep. The process of transforming milk into cheese involves the use of bacteria and enzymes, which coagulate the milk proteins and separate the curds from the whey. This biological and chemical process is distinctly different from meat production, which involves the slaughter and processing of animals for their muscle tissue. Understanding this distinction is crucial for dietary choices, especially for those following vegetarian or vegan lifestyles, as cheese remains a permissible food item in many plant-based diets.

From a nutritional standpoint, cheese and meat serve different roles. Meat is a primary source of protein, iron, and B vitamins, while cheese provides protein, calcium, and phosphorus. However, the production methods and ingredient profiles diverge significantly. For instance, rennet, an enzyme complex traditionally derived from the stomachs of ruminant animals, is often used in cheese making to curdle milk. While this might sound animal-derived, vegetarian alternatives like microbial rennet are widely available, ensuring cheese can be produced without any meat-related components. This highlights the flexibility in cheese production to cater to diverse dietary needs.

To illustrate the cheese-making process, consider the following steps: milk is first pasteurized to eliminate harmful bacteria, then inoculated with specific bacterial cultures to acidify the milk. Next, rennet or a suitable alternative is added to coagulate the milk, forming curds. These curds are then cut, stirred, and heated to release whey, after which they are pressed into molds to form cheese. This method relies entirely on milk and microbial agents, with no meat involvement. For home cheese makers, starter kits often include vegetarian rennet tablets, making it easy to produce cheese without animal-derived enzymes.

A comparative analysis between cheese and meat production reveals further contrasts. Meat production is resource-intensive, requiring large amounts of feed, water, and land for livestock. In contrast, cheese production, while still impactful, primarily depends on milk, which can be sourced from animals already part of the dairy industry. Additionally, the use of bacteria and enzymes in cheese making is a precise science, allowing for controlled and efficient production. This efficiency, combined with the absence of meat, positions cheese as a distinct food category, both in terms of ingredients and environmental footprint.

In practical terms, knowing that cheese is made from milk and not meat empowers consumers to make informed dietary choices. For example, individuals with lactose intolerance can opt for aged cheeses, which contain lower lactose levels due to the fermentation process. Similarly, those avoiding animal products entirely can seek out cheeses made with plant-based rennet. By understanding the ingredients and processes behind cheese, consumers can better align their food choices with their health and ethical values. This knowledge also dispels misconceptions, ensuring cheese remains a versatile and accessible food item across various diets.

Have Wise Cheese Waffles Evolved? A Tasty Update on a Classic Snack

You may want to see also

Dietary Classification: Cheese is dairy, not meat, and is vegetarian-friendly in most cases

Cheese is fundamentally a dairy product, derived from milk through a process of curdling and aging. This classification stems from its primary ingredient—milk—which is obtained from animals like cows, goats, or sheep. Unlike meat, which comes from the muscle tissue of animals, cheese is a transformation of milk proteins, fats, and sugars. Understanding this distinction is crucial for dietary choices, as it clarifies why cheese is not considered meat and aligns with vegetarian dietary guidelines.

For vegetarians, cheese is generally a staple, provided it is made without animal-derived rennet. Traditional rennet, an enzyme complex, is sourced from the stomach lining of ruminant animals, making it unsuitable for strict vegetarians. However, most modern cheeses use microbial or plant-based rennet, ensuring they remain vegetarian-friendly. To verify, check labels for terms like "microbial enzyme" or "vegetarian-friendly," or opt for brands known for using non-animal rennet. This simple step ensures alignment with vegetarian principles while enjoying cheese.

From a nutritional standpoint, cheese offers a unique profile distinct from meat. While meat is rich in protein and iron, cheese provides calcium, phosphorus, and vitamin B12, essential for bone health and nerve function. A 1-ounce serving of cheddar cheese, for instance, contains about 7 grams of protein and 20% of the daily recommended calcium intake. For vegetarians, cheese can be a valuable protein source, but moderation is key due to its saturated fat content. Pairing cheese with plant-based foods like whole grains or vegetables balances its nutritional impact.

Comparatively, cheese and meat serve different roles in dietary planning. Meat is often the centerpiece of a meal, providing bulk and satiety, whereas cheese is typically used as a flavor enhancer or complement. For example, a vegetarian might use cheese to add richness to a vegetable lasagna or sprinkle it on a salad for added protein. This versatility makes cheese a practical ingredient for vegetarians, bridging the gap between plant-based and animal-derived foods without crossing into meat territory.

In practical terms, incorporating cheese into a vegetarian diet requires mindful selection and portion control. Opt for low-fat varieties like mozzarella or feta to reduce saturated fat intake, and pair cheese with fiber-rich foods to support digestion. For children and older adults, cheese can be a convenient way to meet calcium needs, but portion sizes should align with age-specific dietary recommendations. By understanding cheese’s dairy classification and its vegetarian-friendly nature, individuals can confidently include it in their diets while adhering to their dietary principles.

Why Epoisses Cheese is Banned in Some Countries: Uncovering the Truth

You may want to see also

Production Process: Rennet, often animal-derived, is used but doesn’t classify cheese as meat

Cheese production relies heavily on rennet, an enzyme complex traditionally sourced from the stomach lining of ruminant animals like calves, lambs, and goats. This animal-derived ingredient plays a pivotal role in curdling milk, separating it into solid curds (which become cheese) and liquid whey. Despite its animal origin, rennet’s function is purely biochemical—it cleaves the milk protein κ-casein, destabilizing the milk’s structure. This process, while essential, does not transform cheese into a meat product. Meat classification requires tissue from muscles or organs, a criterion cheese fails to meet regardless of rennet’s source.

Consider the analogy of gelatin, often derived from animal bones and skin but used in desserts like jelly. Just as gelatin’s animal origin doesn’t classify sweets as meat, rennet’s role in cheese is similarly categorical. Modern cheese production offers alternatives like microbial or plant-based rennet (e.g., from *Mucor miehei* fungus or thistle flowers), which further decouples cheese from animal-product dependency. However, even when animal-derived rennet is used, the end product remains dairy, not meat. The distinction lies in the source of the material (milk) and the biochemical process, not the enzyme’s origin.

For those concerned about dietary restrictions, understanding rennet’s role is key. Animal-derived rennet is typically used in hard cheeses like Parmesan or Cheddar, while softer cheeses often rely on microbial alternatives. Labels like "suitable for vegetarians" indicate non-animal rennet use. Dosage varies by type: animal rennet is used at 0.02–0.05% of milk weight, while microbial rennet may require 0.1–0.2% due to lower potency. Practical tip: If avoiding animal products entirely, opt for cheeses labeled "microbial enzyme" or "plant-based coagulant."

A comparative analysis highlights the difference between rennet and meat production. Meat involves slaughter and tissue extraction, whereas cheese begins with milk—a renewable resource obtained without harming the animal. Rennet’s animal origin is a byproduct of the meat industry, but its use in cheese is a secondary, non-tissue-based application. This distinction is legally recognized in food classification systems worldwide, ensuring cheese remains categorized as dairy, not meat. For instance, the FDA defines cheese as a milk-derived product, irrespective of rennet type.

In conclusion, while rennet’s animal origin may raise questions, its role in cheese production is biochemical, not categorical. Cheese’s classification as dairy stems from its milk base and manufacturing process, not the enzymes used. Whether animal-derived or synthetic, rennet serves as a tool, not a defining ingredient. This clarity is essential for consumers navigating dietary choices, ensuring cheese remains a distinct food category, separate from meat products.

Uncovering the Surprising Age of Cheese Whiz: A Tasty History

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Nutritional Comparison: Cheese lacks meat’s protein and iron but contains calcium and fat

Cheese and meat are often lumped together in dietary discussions, yet their nutritional profiles diverge sharply. While both are staples in many diets, cheese cannot replace meat in terms of protein and iron content. A 100-gram serving of ground beef provides approximately 26 grams of protein and 2.7 milligrams of iron, whereas the same amount of cheddar cheese offers only 25 grams of protein and 0.7 milligrams of iron. This gap highlights why cheese, despite its richness, falls short as a meat substitute in these key nutrients.

To bridge the nutritional divide, consider pairing cheese with iron-rich plant foods like spinach or lentils. For instance, a meal combining 50 grams of cheese with a cup of cooked spinach (3.6 milligrams of iron) can enhance iron intake while maintaining protein levels. This strategy is particularly useful for vegetarians or those reducing meat consumption. However, it’s crucial to monitor portion sizes, as cheese’s high fat content—around 33 grams per 100 grams of cheddar—can contribute to excess calorie intake if not managed carefully.

From a developmental perspective, cheese’s calcium content makes it a valuable addition to diets, especially for children and adolescents. A single ounce of cheese provides roughly 200 milligrams of calcium, contributing to the 1,300 milligrams daily requirement for 9- to 18-year-olds. In contrast, meat offers negligible calcium, making cheese a superior choice for bone health. Yet, its lower protein and iron levels mean it should complement, not replace, meat in growing diets.

For adults, particularly older individuals, cheese’s fat content warrants attention. While fats are essential for nutrient absorption and satiety, the saturated fats in cheese—about 21 grams per 100 grams of cheddar—can elevate LDL cholesterol levels when consumed in excess. The American Heart Association recommends limiting saturated fats to 5-6% of daily calories, roughly 13 grams for a 2,000-calorie diet. Balancing cheese intake with lean protein sources like poultry or legumes can mitigate this risk while ensuring a well-rounded nutrient profile.

In summary, cheese and meat serve distinct nutritional roles. Cheese excels in calcium and fat but lacks the protein and iron density of meat. Tailoring intake to specific dietary needs—whether for bone health, calorie management, or nutrient balance—requires understanding these differences. Pairing cheese strategically with other foods can address its shortcomings, making it a versatile component of a balanced diet rather than a direct meat substitute.

Switching to Loaf Processed Cheese: A Simple Substitute Guide

You may want to see also

Cultural Perception: Some cultures view cheese as non-meat, while others debate its status

Cheese, a dairy product derived from milk, is universally recognized as non-meat in most cultures. However, its status becomes nuanced when examined through the lens of dietary laws, religious practices, and regional customs. For instance, in Jewish dietary laws (kashrut), cheese is considered pareve—neither meat nor dairy—only if it is produced without rennet derived from animals slaughtered without proper ritual. This distinction highlights how cultural and religious frameworks can complicate the seemingly straightforward classification of cheese.

In contrast, some South Asian cultures, particularly in India, often categorize cheese (like paneer) as a vegetarian protein source, distinct from meat but serving a similar culinary role. Here, the perception of cheese is shaped by its function in meals rather than its biological origin. This pragmatic approach underscores how cultural utility can override strict definitions, positioning cheese as a versatile ingredient that transcends binary classifications.

The debate intensifies in regions where dietary restrictions blur the lines between animal-derived products. For example, in certain vegan communities, cheese—even if plant-based—is sometimes debated for its mimicry of dairy, raising questions about its ethical and cultural alignment. This discourse illustrates how cultural perception can extend beyond ingredients to encompass values and intentions, further complicating cheese’s status in diverse contexts.

To navigate these cultural nuances, consider practical steps: when hosting international guests, clarify dietary preferences explicitly, especially regarding dairy and meat. For instance, label dishes containing cheese as “dairy” or “vegetarian” to avoid confusion. In educational settings, incorporate lessons on global food classifications to foster cross-cultural understanding. By acknowledging these variations, individuals can respect and adapt to the diverse ways cheese is perceived and consumed worldwide.

Finding Mascarpone Cheese: A Guide to Its Store Location

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, cheese is not a meat product. It is a dairy product made from milk, typically through the process of curdling and draining.

Cheese does not contain animal meat. It is made from milk, which is an animal byproduct, but it does not include flesh or tissue from animals.

Yes, most vegetarians can eat cheese because it is not a meat product. However, some vegetarians may avoid certain cheeses that use animal-derived rennet in their production.