The question of whether cheese qualifies as an ultra-processed food (UPF) has sparked considerable debate among nutritionists and food scientists. While UPFs are typically characterized by their industrial formulation, inclusion of additives, and minimal whole food ingredients, cheese’s classification is less straightforward. Traditional cheeses, such as cheddar or mozzarella, are made from milk through processes like fermentation and coagulation, which some argue preserve their natural origins. However, highly processed cheese products, like cheese spreads or flavored snacks, often contain additives, preservatives, and artificial ingredients, aligning more closely with the UPF definition. This distinction highlights the importance of considering both the production method and the final product’s composition when evaluating whether cheese falls into the UPF category.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition of UPF (Ultra-Processed Food) | Foods formulated by industry, often with additives, to be highly convenient, palatable, and profitable. Typically contain little to no whole foods. |

| Cheese Classification | Generally not considered a UPF. Most cheeses are minimally processed and made from whole milk, salt, and cultures. |

| Exceptions | Highly processed cheese products (e.g., cheese spreads, flavored cheese snacks, or imitation cheese) may be classified as UPF due to added preservatives, flavors, and emulsifiers. |

| Processing Level | Traditional cheeses (e.g., cheddar, mozzarella, gouda) undergo minimal processing (curdling, pressing, aging). |

| Nutritional Profile | Natural cheeses provide protein, calcium, and vitamins. UPF cheeses may have lower nutritional value due to added ingredients. |

| Additives | Natural cheeses typically contain no additives. UPF cheese products may include stabilizers, colorings, and artificial flavors. |

| Health Impact | Natural cheeses are part of a balanced diet. UPF cheese products may contribute to overconsumption of sodium, saturated fats, and additives. |

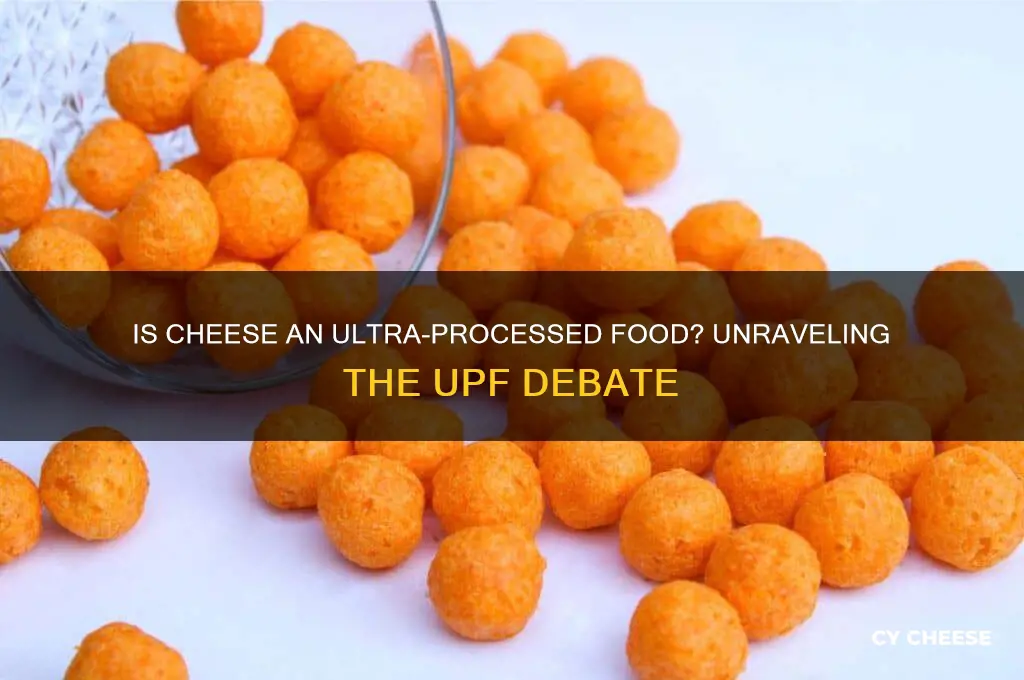

| Examples of UPF Cheese | Cheese puffs, processed cheese slices, cheese-flavored snacks, and cheese spreads. |

| Examples of Non-UPF Cheese | Cheddar, mozzarella, feta, brie, and other traditional cheeses made with minimal ingredients. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Definition of UPFs: Understanding ultra-processed foods and their classification criteria

- Cheese Processing Levels: Examining how different cheese types are processed

- Ingredient Analysis: Investigating additives and preservatives in cheese production

- Health Implications: Exploring potential health effects of consuming processed cheese

- Expert Opinions: Reviewing nutritionist and scientist views on cheese as a UPF

Definition of UPFs: Understanding ultra-processed foods and their classification criteria

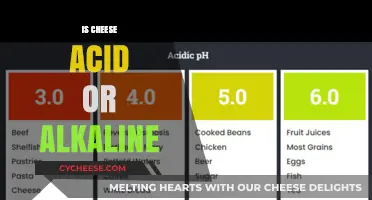

Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) are industrially formulated products derived from substances extracted from whole foods, with the addition of chemicals not typically used in home cooking. These include flavorings, colors, sweeteners, and preservatives designed to enhance taste, texture, and shelf life. The NOVA classification system, developed by researchers, categorizes foods into four groups based on processing levels, with UPFs falling into the fourth and most processed category. Understanding this definition is crucial for evaluating whether cheese—a product of milk curdling and aging—qualifies as a UPF.

To classify cheese as a UPF, one must scrutinize its production process. Traditional cheeses like cheddar or mozzarella involve minimal additives, relying on natural fermentation and aging. However, processed cheese products, such as singles or spreads, often contain emulsifiers, artificial flavors, and stabilizers to improve meltability and extend shelf life. These additions align with the UPF criteria, blurring the line between natural and ultra-processed cheese varieties.

The classification of cheese as a UPF depends on its specific type and ingredients. Artisanal or minimally processed cheeses, made with salt, enzymes, and milk, do not meet UPF criteria. Conversely, highly processed cheese products, laden with additives like sodium phosphate or sorbic acid, fall squarely into the UPF category. Consumers should examine labels for additives like E numbers (e.g., E330, E452) or terms like "modified food starch" to identify UPFs.

From a health perspective, distinguishing between minimally processed and ultra-processed cheese is essential. Studies link high UPF consumption to increased risks of obesity, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes. While cheese provides nutrients like calcium and protein, opting for natural varieties over processed ones can mitigate potential health risks. Practical tips include choosing block cheese over pre-packaged slices and verifying ingredient lists for additives.

In conclusion, cheese’s classification as a UPF hinges on its processing and additives. Traditional cheeses remain outside this category, while processed cheese products embody UPF characteristics. By understanding the NOVA classification and scrutinizing labels, consumers can make informed choices, prioritizing whole foods over ultra-processed alternatives for better health outcomes.

Mastering the Art of Cutting Tetilla Cheese: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Cheese Processing Levels: Examining how different cheese types are processed

Cheese, a beloved staple in diets worldwide, varies widely in its processing levels, which directly influence its classification as a minimally processed or ultra-processed food (UPF). Understanding these processing levels is crucial for discerning its nutritional impact and health implications. Artisanal cheeses like cheddar or gouda typically undergo minimal processing, involving pasteurization, culturing, and aging. These steps preserve natural enzymes and probiotics, offering health benefits such as improved gut health. In contrast, highly processed cheese products, such as cheese spreads or flavored cheese snacks, often include additives like emulsifiers, artificial flavors, and preservatives, pushing them into the UPF category.

Consider the journey of mozzarella, a cheese commonly used in pizzas and salads. Traditional mozzarella is made by stretching and molding curds from buffalo or cow’s milk, with minimal additives. This process retains its natural texture and flavor, classifying it as minimally processed. However, pre-shredded or low-moisture mozzarella often contains anti-caking agents like cellulose or natamycin to extend shelf life, blurring the line between natural and processed. For health-conscious consumers, opting for block mozzarella and grating it at home avoids these additives, ensuring a purer product.

The processing of soft cheeses like cream cheese or brie highlights another spectrum. Cream cheese, for instance, is often homogenized and blended with stabilizers like carob bean gum or xanthan gum to achieve its smooth texture. While these additives are generally recognized as safe, they increase its processing level. Brie, on the other hand, relies on natural mold growth and aging, maintaining its status as a minimally processed food. When selecting soft cheeses, checking ingredient lists for additives like citric acid or artificial thickeners can help differentiate between lightly and heavily processed options.

Hard cheeses such as parmesan or pecorino exemplify minimal processing, as they are primarily aged to reduce moisture and concentrate flavor. These cheeses are rich in nutrients like calcium and protein, with no added preservatives. However, pre-grated versions often contain additives to prevent clumping, reducing their nutritional integrity. A practical tip is to purchase whole blocks and grate them as needed, ensuring maximum freshness and minimal processing.

In summary, cheese processing levels vary significantly, impacting their classification as UPFs. By understanding these differences, consumers can make informed choices. Opting for artisanal, block, or aged cheeses minimizes exposure to additives, while avoiding pre-packaged or flavored varieties reduces UPF intake. Prioritizing whole, minimally processed cheeses not only enhances nutritional value but also aligns with healthier dietary patterns.

Already Have Cheese? Creative Ways to Elevate Your Culinary Creations

You may want to see also

Ingredient Analysis: Investigating additives and preservatives in cheese production

Cheese, a staple in diets worldwide, often escapes scrutiny as a potentially ultra-processed food (UPF). Yet, its production frequently involves additives and preservatives that warrant closer examination. While traditional cheeses rely on simple ingredients like milk, salt, and cultures, modern varieties may include emulsifiers, stabilizers, and artificial flavors to enhance texture, shelf life, or appearance. This raises the question: does the presence of these additives classify cheese as a UPF, and what are the implications for health-conscious consumers?

Analyzing common cheese additives reveals a spectrum of purposes and potential concerns. For instance, natamycin, a preservative used in shredded or sliced cheese, inhibits mold growth but is generally recognized as safe (GRAS) by the FDA. However, carrageenan, an emulsifier found in processed cheese slices, has sparked debate due to studies linking it to gastrointestinal inflammation in animal models. Dosage matters—the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) sets a maximum limit of 1,000 mg/kg for carrageenan in cheese, but even within these bounds, sensitive individuals may experience adverse effects. This highlights the need for consumers to scrutinize labels and consider the cumulative impact of additives across their diet.

From a practical standpoint, reducing exposure to questionable additives in cheese is achievable through informed choices. Opting for raw milk cheeses or those labeled "additive-free" minimizes the risk of consuming synthetic ingredients. For example, aged cheddar or Parmesan typically contain only milk, salt, and cultures, making them less processed alternatives. Additionally, homemade cheese allows full control over ingredients, though this requires time and specific equipment. For those relying on store-bought options, prioritizing brands with shorter ingredient lists and recognizable components can significantly reduce additive intake.

Comparatively, the debate over cheese as a UPF underscores broader issues in food classification. While the NOVA classification system defines UPFs as formulations of ingredients derived from foods or synthesized in labs, cheese’s categorization remains ambiguous. Artisanal varieties align more closely with minimally processed foods, whereas highly processed cheese products, like singles or spreads, fit the UPF criteria due to their additive content. This distinction emphasizes the importance of context—not all cheese is created equal, and its UPF status depends on production methods and ingredient transparency.

In conclusion, ingredient analysis reveals that cheese’s UPF classification hinges on its additives and processing. While some preservatives and emulsifiers serve functional roles, their potential health impacts cannot be ignored. By understanding these additives and making informed choices, consumers can enjoy cheese as part of a balanced diet while minimizing exposure to ultra-processed elements. The key lies in reading labels, prioritizing whole-food options, and recognizing that not all cheese is processed equally.

Mastering the Art of Cheese Conversations: Tips for Enthusiasts

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Health Implications: Exploring potential health effects of consuming processed cheese

Processed cheese, often labeled as a convenient snack or ingredient, falls under the category of ultra-processed foods (UPFs) due to its extensive modification and additive content. Unlike natural cheeses, processed varieties undergo emulsification, melting, and the addition of preservatives, colorings, and flavor enhancers. This transformation raises concerns about its health implications, particularly when consumed regularly. Understanding the potential effects of processed cheese on the body is crucial for making informed dietary choices.

One of the primary health concerns associated with processed cheese is its high sodium content. A single slice can contain up to 300 mg of sodium, contributing significantly to daily intake. Excessive sodium consumption is linked to hypertension, a major risk factor for cardiovascular diseases. For individuals over 50 or those with pre-existing heart conditions, limiting processed cheese intake to no more than 2-3 servings per week is advisable. Pairing it with potassium-rich foods like bananas or spinach can help mitigate sodium’s effects.

Another issue lies in the presence of artificial additives and emulsifiers, such as sodium phosphate and carrageenan, which are used to improve texture and shelf life. Emerging research suggests that these additives may disrupt gut microbiota, leading to inflammation and metabolic disorders. A study published in *Cell Metabolism* found that emulsifiers in processed foods can alter gut bacteria, increasing the risk of obesity and insulin resistance. To minimize exposure, opt for natural cheeses or processed varieties with simpler ingredient lists, avoiding those with unpronounceable additives.

Processed cheese also tends to be higher in saturated fats compared to its natural counterparts. While saturated fats are not inherently harmful in moderation, excessive intake can elevate LDL cholesterol levels, increasing the risk of atherosclerosis. For adults, the American Heart Association recommends limiting saturated fat intake to 5-6% of daily calories. Substituting processed cheese with low-fat natural cheeses or plant-based alternatives can be a healthier option, especially for those monitoring cholesterol levels.

Lastly, the convenience of processed cheese often leads to overconsumption, particularly among children and adolescents. Its palatable flavor and long shelf life make it a staple in school lunches and snacks. However, regular intake of UPFs, including processed cheese, has been associated with poor dietary quality and increased risk of obesity. Parents can encourage healthier habits by offering whole foods like fruit, nuts, or natural cheese sticks as alternatives. Moderation and mindful consumption remain key to balancing convenience with nutritional well-being.

Does Gold Cheese Exist? Unraveling the Myth of Luxury Dairy

You may want to see also

Expert Opinions: Reviewing nutritionist and scientist views on cheese as a UPF

Cheese, a staple in diets worldwide, often sparks debate among nutritionists and scientists regarding its classification as an ultra-processed food (UPF). The NOVA classification system, widely used in nutritional science, categorizes foods based on processing levels. While cheese undergoes processing—fermentation, pasteurization, and sometimes additives—experts argue whether it fits the UPF criteria, which typically include industrial formulations, artificial ingredients, and minimal whole-food content. This distinction matters because UPFs are linked to adverse health outcomes, such as obesity and cardiovascular disease.

Analyzing the Process: Is Cheese Ultra-Processed?

Nutritionists like Dr. Marion Nestle emphasize that not all processed foods are equal. Cheese, particularly artisanal varieties, retains nutritional value from its whole-food origins—milk. Fermentation introduces beneficial bacteria, and aging enhances flavor without relying on synthetic additives. However, mass-produced cheeses often contain emulsifiers, preservatives, and artificial flavors, blurring the line. Scientists like Kevin Hall highlight that the degree of processing, not the act itself, determines UPF status. For instance, cheddar made from raw milk and microbial cultures differs vastly from processed cheese slices laden with stabilizers.

Comparative Insights: Cheese vs. Recognized UPFs

Contrast cheese with undisputed UPFs like sugary cereals or packaged snacks. Unlike these products, cheese provides protein, calcium, and vitamins B12 and K2. A 2020 study in *The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition* found that moderate cheese consumption did not correlate with UPF-related health risks. Yet, Dr. Carlos Monteiro, creator of the NOVA system, cautions that even minimally processed foods can contribute to poor dietary patterns if consumed excessively. The key lies in context: a slice of aged gouda differs nutritionally and metabolically from a highly processed cheese product.

Practical Takeaways: Navigating Cheese Consumption

For those concerned about UPFs, focus on cheese’s origin and ingredient list. Opt for varieties with minimal additives—look for labels listing only milk, salt, enzymes, and cultures. Limit processed cheese products, which often contain phosphates and artificial colors. Nutritionist recommendations suggest capping daily intake at 30–40 grams (1–1.5 ounces) for adults, balancing flavor with health. Pair cheese with fiber-rich foods like whole-grain crackers or vegetables to mitigate potential metabolic impacts. Ultimately, cheese’s UPF status remains nuanced, but informed choices can align it with a wholesome diet.

Mastering the Art of Cheesing Kandura: Tips and Tricks

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheese is generally not classified as a UPF. Most cheeses are minimally processed and made from natural ingredients like milk, salt, and enzymes, making them a whole or lightly processed food.

While traditional cheeses are not UPFs, some highly processed cheese products (e.g., cheese spreads, flavored cheese snacks, or imitation cheese) may contain additives, preservatives, or artificial ingredients, potentially qualifying them as UPFs.

Check the ingredient list. If the cheese contains additives like emulsifiers, artificial flavors, or preservatives, or if it’s heavily modified (e.g., cheese-based snacks), it may be considered ultra-processed. Natural cheeses typically have simple, recognizable ingredients.