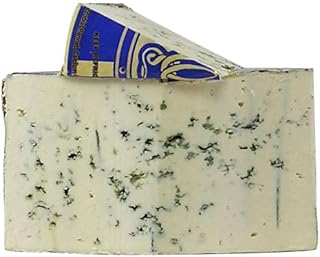

Roquefort cheese, a renowned French blue cheese, owes its distinctive flavor, aroma, and appearance to the presence of a specific chemical compound known as penicillin roqueforti. This compound is produced by the Penicillium roqueforti fungus, which is intentionally introduced during the cheese-making process. As the fungus grows within the cheese, it releases enzymes that break down fats and proteins, contributing to the cheese's creamy texture and complex flavor profile. Penicillin roqueforti is also responsible for the development of the characteristic blue-green veins that run throughout the cheese, making it a key component in the unique sensory experience of Roquefort.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Chemical Name | Penicillin |

| Specific Compound | Penicillin G (Benzylpenicillin) |

| Source in Roquefort Cheese | Produced by Penicillium roqueforti fungus during fermentation |

| Function in Cheese | Contributes to flavor, aroma, and texture development |

| Antibacterial Properties | Yes, but primarily contributes to cheese ripening rather than medicinal use |

| Concentration | Varies, typically present in trace amounts |

| Health Implications | Generally safe for consumption, unless allergic to penicillin |

| Discovery | Penicillin was first discovered by Alexander Fleming in 1928, but its presence in Roquefort cheese has been utilized for centuries |

| Regulation | Controlled by food safety standards to ensure safe levels of penicillin |

| Flavor Contribution | Earthy, nutty, and pungent notes characteristic of Roquefort cheese |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Penicillium Roqueforti: Fungus responsible for Roquefort's distinctive blue veins and unique flavor profile

- Methyl Ketones: Compounds produced by the fungus, contributing to the cheese's sharp, tangy aroma

- Proteolysis: Enzymatic breakdown of proteins by the fungus, enhancing texture and flavor complexity

- Lipolysis: Fat breakdown by fungal enzymes, creating creamy texture and nutty, buttery notes

- Geosmin: Earthy-smelling compound produced by the fungus, adding depth to the cheese's aroma

Penicillium Roqueforti: Fungus responsible for Roquefort's distinctive blue veins and unique flavor profile

Roquefort cheese owes its distinctive blue veins and complex flavor profile to *Penicillium roqueforti*, a filamentous fungus that thrives in the cool, damp caves of southern France. This microorganism is not merely a contaminant but a deliberate addition, carefully cultivated to transform ordinary milk into a culinary masterpiece. The fungus produces a network of hyphae that penetrate the cheese, creating the characteristic veins while releasing enzymes and metabolites that contribute to its unique taste and texture.

Analytically speaking, *Penicillium roqueforti* secretes a suite of enzymes, including lipases and proteases, which break down fats and proteins in the cheese. Lipases hydrolyze milk fats into free fatty acids, some of which, like butyric acid and isovaleric acid, impart nutty and fruity notes. Proteases degrade milk proteins into peptides and amino acids, contributing to the cheese’s savory umami flavor. Notably, the fungus also produces methyl ketones, such as 2-heptanone and 2-nonanone, which are responsible for the cheese’s earthy, spicy undertones. These chemical compounds are not found in cheeses aged without *Penicillium roqueforti*, underscoring its indispensable role.

To harness the full potential of *Penicillium roqueforti*, cheesemakers follow precise steps. The process begins with inoculating pasteurized sheep’s milk with a controlled dose of the fungal spores, typically 10^6 to 10^7 spores per milliliter. After coagulation, the curds are pierced to allow oxygen penetration, fostering fungal growth. The cheese is then aged in temperature-controlled caves (7–12°C) with 80–95% humidity for 3–6 months. Caution must be taken to avoid over-inoculation, as excessive fungal activity can lead to bitter flavors or uneven texture. Regular monitoring of pH and moisture levels is essential to ensure optimal conditions for *Penicillium roqueforti* without encouraging unwanted bacteria.

Comparatively, while other blue cheeses like Gorgonzola and Stilton also use *Penicillium* species, Roquefort’s reliance on *Penicillium roqueforti* sets it apart. This specific strain produces a broader spectrum of flavor compounds, including unique volatile organic compounds (VOCs) like dimethyl trisulfide, which contributes to its distinct aroma. Additionally, Roquefort’s protected designation of origin (PDO) status mandates the use of *Penicillium roqueforti* and traditional aging methods, ensuring consistency and authenticity. This contrasts with other blue cheeses, which may use different *Penicillium* strains or aging techniques, resulting in variations in flavor and texture.

Descriptively, the impact of *Penicillium roqueforti* on Roquefort cheese is nothing short of transformative. The fungus’s activity creates a symphony of flavors—creamy yet sharp, with hints of caramel, pepper, and hazelnuts. The blue veins, ranging from pale turquoise to deep indigo, are not just visually striking but also indicators of the fungus’s metabolic activity. Each bite offers a tactile experience, with the cheese’s crumbly yet moist texture melting on the palate. This sensory complexity is a testament to the intricate interplay between *Penicillium roqueforti* and its environment, making Roquefort a benchmark for artisanal cheesemaking.

Easy Oven-Baked Eggs and Cheese Recipe for Breakfast Lovers

You may want to see also

Methyl Ketones: Compounds produced by the fungus, contributing to the cheese's sharp, tangy aroma

Roquefort cheese owes its distinctive sharp, tangy aroma to methyl ketones, compounds produced by the fungus *Penicillium roqueforti* during the aging process. These volatile organic compounds are key players in the sensory profile of blue cheeses, contributing to their complex and pungent character. Methyl ketones, such as 2-heptanone and 2-nonanone, are formed through the breakdown of fats by the fungus, creating a unique olfactory signature that sets Roquefort apart from other cheeses.

Analyzing the role of methyl ketones reveals their dual nature: while they enhance the cheese’s aroma, their concentration must be carefully managed. Excessive levels can overpower the palate, leading to an unpleasantly harsh flavor. Cheese makers achieve balance by controlling factors like temperature, humidity, and aging duration. For instance, aging Roquefort at 7–12°C (45–54°F) with 85–95% humidity optimizes methyl ketone production without overwhelming the cheese’s overall profile. This precision ensures the compounds contribute positively to the sensory experience.

From a practical standpoint, understanding methyl ketones can guide cheese enthusiasts in pairing and storage. Their sharp, tangy notes complement sweet accompaniments like honey or fresh fruit, creating a harmonious contrast. When storing Roquefort, wrap it in wax paper to allow breathability, preserving the delicate balance of methyl ketones. Avoid plastic wrap, as it traps moisture and can alter the aroma. Serving the cheese at room temperature for 30 minutes before consumption also enhances the release of these compounds, maximizing their aromatic impact.

Comparatively, methyl ketones in Roquefort differ from those found in other blue cheeses due to the specific strains of *Penicillium roqueforti* used. For example, Gorgonzola and Stilton, while sharing similar fungal processes, exhibit milder methyl ketone profiles, resulting in less assertive aromas. This distinction highlights the importance of fungal strain selection in shaping the sensory characteristics of blue cheeses. Roquefort’s boldness is a testament to the unique interplay between its fungus and the cheese matrix.

In conclusion, methyl ketones are not just byproducts of fungal activity but essential contributors to Roquefort’s identity. Their production is a delicate dance of biology and craftsmanship, requiring careful control to achieve the cheese’s signature aroma. Whether you’re a cheese maker, connoisseur, or casual enthusiast, appreciating the role of these compounds deepens your understanding of Roquefort’s complexity. By mastering their influence, you can better enjoy and preserve this iconic cheese.

Does Takis Cheese Explosion Contain Real Cheese? Uncovering the Truth

You may want to see also

Proteolysis: Enzymatic breakdown of proteins by the fungus, enhancing texture and flavor complexity

Roquefort cheese owes its distinctive texture and flavor to proteolysis, a process driven by enzymes secreted by *Penicillium roqueforti*, the fungus central to its production. These enzymes, including proteases, systematically break down complex milk proteins like casein into smaller peptides and amino acids. This biochemical transformation softens the cheese’s structure, creating its signature creamy yet crumbly mouthfeel. Simultaneously, the liberated amino acids and peptides interact with other compounds, generating the cheese’s complex, savory, and slightly nutty flavor profile. Without proteolysis, Roquefort would lack both its characteristic texture and depth of taste.

To understand proteolysis in Roquefort, consider it a controlled demolition of protein architecture. The fungus’s proteases target specific peptide bonds within casein molecules, cleaving them into fragments. This process is temperature- and time-dependent; optimal proteolysis occurs during aging at 7–12°C over 2–3 months. Producers carefully monitor these conditions to balance protein breakdown: too little yields a firm, bland cheese, while excessive proteolysis can lead to an unpleasantly bitter, mushy product. Practical tip: home cheesemakers should maintain consistent temperatures and periodically test curd texture to gauge proteolysis progress.

Comparatively, proteolysis in Roquefort differs from that in other cheeses due to *P. roqueforti*’s unique enzymatic profile. Unlike surface-ripened cheeses, where bacteria dominate proteolysis, Roquefort relies solely on fungal enzymes. This distinction results in a faster, more aggressive breakdown of proteins, contributing to its distinct attributes. For instance, the amino acid glutamate, released during proteolysis, enhances the cheese’s umami flavor—a hallmark of Roquefort. This contrasts with cheeses like Cheddar, where bacterial proteolysis produces milder, lactic notes.

Persuasively, embracing proteolysis as a key variable in cheese production allows artisans to innovate. By manipulating fungal strains, aging times, or moisture levels, producers can tailor texture and flavor to specific preferences. For example, a shorter aging period preserves more intact proteins, resulting in a firmer cheese with subtler flavors. Conversely, extended aging intensifies proteolysis, yielding a richer, more pungent product. Experimentation with *P. roqueforti* variants could further diversify flavor profiles, appealing to both traditionalists and adventurous palates.

In practice, controlling proteolysis requires precision. Commercial producers often inoculate milk with specific *P. roqueforti* strains selected for their enzymatic activity. Home enthusiasts should source high-quality spores and monitor pH levels, as acidity influences enzyme efficiency. A pH range of 5.0–5.5 is ideal for protease activity. Caution: over-reliance on proteolysis can lead to structural collapse, so periodic sampling is essential. Ultimately, mastering this process unlocks the full potential of Roquefort’s sensory experience, blending science and art in every bite.

Shredded Cheese Measurements: How Many Ounces Fit in a Tab?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Lipolysis: Fat breakdown by fungal enzymes, creating creamy texture and nutty, buttery notes

Roquefort cheese owes its distinctive creamy texture and complex flavor profile to lipolysis, a process driven by fungal enzymes. These enzymes, primarily from *Penicillium roqueforti*, break down fats (lipids) into free fatty acids and glycerol. This biochemical reaction is not merely a byproduct of fermentation but a cornerstone of Roquefort’s sensory identity, contributing to its nutty, buttery notes and velvety mouthfeel.

Analyzing the mechanism, lipolysis in Roquefort begins as *P. roqueforti* colonizes the cheese during aging. The fungus secretes lipases, enzymes that hydrolyze triglycerides into simpler compounds. For instance, a study in the *Journal of Dairy Science* found that lipases from *P. roqueforti* exhibit optimal activity at pH 5.5 and temperatures between 30–37°C, conditions typical of Roquefort’s aging environment. This specificity ensures that fat breakdown occurs gradually, allowing flavors to develop without overwhelming the cheese’s structure.

To replicate or enhance lipolysis in artisanal cheese production, consider these practical steps: inoculate milk with a controlled dose of *P. roqueforti* spores (10^4–10^6 CFU/mL) during coagulation, maintain aging temperatures at 7–12°C to balance enzyme activity and microbial growth, and pierce the cheese regularly to introduce oxygen, which stimulates fungal metabolism. Caution: excessive aeration can lead to off-flavors, so limit piercing to 2–3 times weekly.

Comparatively, lipolysis in Roquefort contrasts with cheddar’s proteolysis-driven aging. While cheddar relies on bacterial enzymes to break down proteins, Roquefort’s fungal lipases target fats, yielding a richer, more unctuous texture. This distinction highlights the role of microbial selection in shaping cheese characteristics, making Roquefort a case study in enzyme-driven flavor development.

Finally, the takeaway for enthusiasts and producers alike is that lipolysis is not just a chemical process but an art. By understanding the interplay of enzymes, temperature, and oxygen, one can manipulate fat breakdown to achieve desired textures and flavors. For home cheesemakers, experimenting with *P. roqueforti* cultures and aging conditions offers a gateway to crafting Roquefort-style cheeses with nuanced, lipolysis-driven profiles.

Carl's Jr. Ham and Cheese Burrito: Fact or Fiction?

You may want to see also

Geosmin: Earthy-smelling compound produced by the fungus, adding depth to the cheese's aroma

Roquefort cheese, a revered French blue cheese, owes much of its distinctive aroma to a compound called geosmin. Produced by the fungus *Penicillium roqueforti* during the cheese’s aging process, geosmin is a volatile organic compound responsible for the earthy, musty scent reminiscent of freshly turned soil after rain. This compound is not unique to Roquefort; it’s also found in beets, rivers, and even drinking water, but its presence in cheese is particularly notable for the depth it adds to the sensory experience.

Analytically, geosmin’s role in Roquefort is a delicate balance. At low concentrations, it enhances the cheese’s complexity, creating a harmonious interplay with other aromatic compounds like methyl ketones and alcohols. However, at higher levels, geosmin can overpower the palate, leading to an off-putting, dirt-like flavor. Cheese makers must carefully control the aging environment to ensure the fungus produces geosmin in optimal amounts—typically measured in parts per trillion (ppt). For instance, concentrations above 20 ppt in water are detectable by humans, but in cheese, the threshold is lower due to the concentrated nature of the product.

From a practical standpoint, understanding geosmin’s role can help cheese enthusiasts appreciate Roquefort’s nuances. Pairing this cheese with beverages that complement its earthy notes, such as a full-bodied red wine or a nutty sherry, can elevate the tasting experience. For home cheese makers, monitoring humidity and temperature during aging is critical to managing geosmin production. A humidity level of 85–90% and a temperature of 7–12°C (45–54°F) are ideal for *Penicillium roqueforti* to thrive while keeping geosmin in check.

Comparatively, geosmin’s impact on Roquefort contrasts with its effect in other foods. In beets, geosmin is often considered a flaw, leading to breeding programs aimed at reducing its presence. In cheese, however, it is celebrated as a hallmark of quality. This duality highlights how context shapes our perception of flavor compounds. While geosmin in water might prompt a call to the utility company, in Roquefort, it’s a sign of craftsmanship.

Descriptively, the aroma of geosmin in Roquefort is like a walk through a damp forest after a storm—rich, grounding, and subtly wild. It’s the olfactory equivalent of a bass note in a symphony, providing a foundation that allows other flavors to shine. When you next savor a piece of Roquefort, take a moment to inhale deeply and let geosmin transport you to the cool, dark caves of southern France where this cheese matures. Its presence is a testament to the intricate dance between microbiology and artistry in cheese making.

Is Your Cheese Pasteurized? Quick Tips to Check and Be Sure

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The distinctive flavor of Roquefort cheese is primarily due to the presence of methyl ketones, particularly 2-heptanone and 2-nonanone, produced by the fungus *Penicillium roqueforti*.

The blue-green veins in Roquefort cheese are caused by the growth of *Penicillium roqueforti*, a fungus that produces pigments such as mycena blue and roquefortine C during fermentation.

The pungent aroma of Roquefort cheese is largely attributed to volatile sulfur compounds, such as methanethiol and dimethyl sulfide, which are byproducts of the metabolic activity of *Penicillium roqueforti*.

Roquefort cheese contains natural preservatives like natamycin (pimaricin), an antifungal compound produced by *Streptomyces natalensis*, which helps inhibit the growth of unwanted molds and bacteria during aging.