When high-temperature cheese, such as those processed at elevated temperatures to improve meltability and shelf life, is frozen, several changes occur. The freezing process causes the moisture within the cheese to form ice crystals, which can disrupt the protein matrix and fat globules, potentially leading to a grainy or crumbly texture upon thawing. Additionally, the fat may separate from the solids, resulting in a greasy appearance or mouthfeel. While freezing can extend the cheese's storage life, it often compromises its original texture, flavor, and functionality, particularly in high-temperature varieties designed for specific culinary applications like melting or slicing.

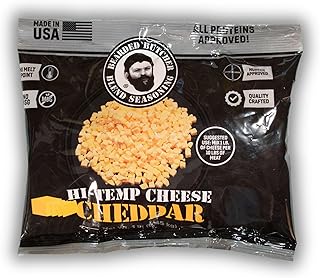

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Texture Changes: Freezing alters cheese texture, making it crumbly or grainy due to fat and moisture separation

- Flavor Impact: Cold temperatures mute flavors, reducing sharpness and complexity in high-temperature cheeses

- Moisture Loss: Freezing can cause moisture to crystallize, leading to drier cheese upon thawing

- Fat Separation: High-fat cheeses may show visible fat separation, affecting consistency and appearance

- Shelf Life Extension: Freezing prolongs cheese life but risks quality degradation over extended storage periods

Texture Changes: Freezing alters cheese texture, making it crumbly or grainy due to fat and moisture separation

Freezing high-temperature cheese disrupts its delicate balance of fat and moisture, leading to noticeable texture changes. When cheese is subjected to freezing temperatures, the water within its structure forms ice crystals. These crystals act like tiny wedges, forcing fat globules apart and causing them to coalesce into larger clusters. Upon thawing, the ice melts, leaving behind pockets of separated fat and a weakened protein matrix. This results in a crumbly or grainy texture, a far cry from the smooth, cohesive mouthfeel of fresh cheese.

High-fat cheeses like cheddar or Gruyère are particularly susceptible to this transformation. Their higher fat content provides more material for separation, exacerbating the textural changes. Conversely, lower-fat cheeses like mozzarella or ricotta may exhibit less pronounced graininess due to their lower fat content.

Understanding this process allows for informed decisions when freezing cheese. For instance, if a recipe calls for grated cheese, freezing and thawing a high-fat variety might be advantageous, as the resulting crumbly texture would be ideal for sprinkling. However, for applications requiring a smooth melt, such as sauces or fondues, freezing should be avoided.

It's crucial to note that while freezing alters texture, it doesn't necessarily render cheese inedible. The flavor profile often remains intact, making frozen cheese suitable for cooking or baking where texture is less critical.

To minimize texture changes, consider freezing cheese in smaller portions. This reduces the amount of cheese exposed to air and moisture during thawing, potentially mitigating fat separation. Additionally, wrapping cheese tightly in plastic wrap or aluminum foil before freezing can help prevent moisture loss and slow down the formation of large ice crystals.

Average Cheese Package Sizes: How Many Slices Are Typically Included?

You may want to see also

Flavor Impact: Cold temperatures mute flavors, reducing sharpness and complexity in high-temperature cheeses

Freezing high-temperature cheeses like Parmesan or Gruyère doesn’t just pause their shelf life—it fundamentally alters their flavor profile. Cold temperatures act as a silencer, dampening the volatile compounds responsible for sharpness and complexity. These compounds, such as esters and aldehydes, become less active at low temperatures, resulting in a muted sensory experience. For instance, a frozen aged cheddar loses its tangy bite, while a frozen Asiago becomes bland and one-dimensional. Understanding this mechanism is crucial for anyone aiming to preserve or serve these cheeses optimally.

To mitigate flavor loss, consider a two-step thawing process. First, transfer the frozen cheese from the freezer to the refrigerator 24 hours before use. This gradual thawing minimizes moisture migration, which can dilute flavors further. Second, let the cheese sit at room temperature for 30–60 minutes before serving. This reactivates the volatile compounds, partially restoring sharpness and complexity. For grated high-temperature cheeses, skip thawing altogether—use them directly from frozen in cooking applications like sauces or baked dishes, where heat will revive some of the lost flavor.

A comparative analysis reveals that younger, less complex cheeses fare better in the freezer than their aged counterparts. For example, a 6-month aged Gouda retains more of its nutty notes post-freezing than a 24-month aged Parmesan, which loses its crystalline texture and umami punch. This is because longer aging concentrates flavor compounds that are more susceptible to cold-induced suppression. If freezing is unavoidable, prioritize younger cheeses or plan to use the thawed product in applications where texture, not flavor, is the star.

Persuasively, freezing should be a last resort for high-temperature cheeses, especially those prized for their bold flavors. Instead, invest in proper storage—wrap cheeses tightly in parchment paper followed by plastic wrap to prevent moisture loss, and store them in the least cold part of the refrigerator. For long-term preservation, vacuum sealing is superior to freezing, as it maintains both flavor and texture. If freezing is necessary, label the cheese with the date and plan to consume it within 6 months, as flavor degradation accelerates beyond this point.

Perfect Party Planning: Meat and Cheese Trays for 75 Guests

You may want to see also

Moisture Loss: Freezing can cause moisture to crystallize, leading to drier cheese upon thawing

Freezing high-temperature cheese, such as those processed at elevated heat levels (e.g., mozzarella or cheddar), triggers a unique interaction between moisture and temperature. When these cheeses are subjected to freezing, water molecules within their structure begin to crystallize, forming ice crystals. This process disrupts the cheese’s matrix, causing moisture to separate from the protein and fat components. Upon thawing, the ice crystals melt, but the moisture does not fully reintegrate into the cheese, resulting in a drier texture. This phenomenon is particularly noticeable in high-temperature cheeses due to their lower moisture content and denser structure compared to fresh cheeses.

To mitigate moisture loss, consider pre-portioning cheese before freezing. Smaller pieces expose less surface area to air, reducing the risk of dehydration. Wrap each portion tightly in plastic wrap, followed by a layer of aluminum foil or place it in an airtight container. For optimal results, freeze cheese at 0°F (-18°C) or below, as this temperature slows the formation of large ice crystals, which are more damaging to the cheese’s structure. Label the packaging with the freezing date, as high-temperature cheeses can be stored for up to 6 months without significant quality loss, though moisture loss may still occur.

A comparative analysis reveals that high-temperature cheeses fare better than softer varieties when frozen, but their texture and flavor are still compromised. For instance, frozen mozzarella may become crumbly and less stretchy, while cheddar can develop a grainy mouthfeel. This is because the heat-induced protein alignment in these cheeses, which gives them their characteristic melt and texture, is disrupted by the crystallization and subsequent migration of moisture. In contrast, fresh cheeses like ricotta or feta, with higher moisture content, often become unpalatably dry and separated when frozen.

Practically, if you’ve thawed high-temperature cheese and noticed excessive dryness, rehydrate it by incorporating it into dishes with high moisture content, such as sauces, soups, or casseroles. For example, grated frozen cheddar can be added directly to a macaroni and cheese sauce during cooking, allowing it to blend seamlessly. Avoid refreezing thawed cheese, as this exacerbates moisture loss and further degrades texture. Instead, use thawed cheese within 3–5 days and monitor for signs of spoilage, such as off odors or mold.

In conclusion, while freezing is a convenient way to extend the shelf life of high-temperature cheese, it inevitably leads to moisture loss due to crystallization. By understanding this process and implementing practical storage and usage techniques, you can minimize the impact on texture and flavor. Treat frozen cheese as an ingredient rather than a standalone product, and you’ll find it remains a versatile addition to your culinary repertoire.

Discover the Exact Ounce Measurement of Individual Velveeta Cheese Portions

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Fat Separation: High-fat cheeses may show visible fat separation, affecting consistency and appearance

Freezing high-fat cheeses like cheddar or Gruyère often leads to visible fat separation, a phenomenon where the lipid-rich components detach from the protein matrix. This occurs because fats and proteins have different freezing points and expansion rates, causing them to separate as the cheese cools. The result? A grainy texture and oily pockets that mar the cheese’s once-smooth consistency. For instance, a block of aged cheddar, when thawed after freezing, may exhibit a greasy surface or crumbly interior, making it less appealing for slicing or melting.

To mitigate fat separation, consider portioning high-fat cheeses into smaller pieces before freezing. This reduces the surface area where fats can accumulate and allows for quicker thawing, minimizing structural damage. Wrap the cheese tightly in plastic wrap, followed by aluminum foil, to create a barrier against moisture and air. For optimal results, freeze at 0°F (-18°C) or below, and thaw slowly in the refrigerator rather than at room temperature. Avoid refreezing, as repeated temperature changes exacerbate separation and degrade texture further.

From a culinary perspective, fat separation in frozen high-fat cheeses isn’t always a dealbreaker. While it compromises appearance and texture for charcuterie boards or sandwiches, separated cheeses can still perform well in cooked applications. Melted into sauces, soups, or casseroles, the fat redistributes, restoring creaminess and flavor. For example, a frozen, fat-separated Gruyère can be grated and incorporated into a béchamel sauce for mornay, where its altered texture becomes imperceptible.

The takeaway? Freezing high-fat cheeses is a trade-off. While it extends shelf life, fat separation is nearly inevitable, particularly in cheeses with over 30% milk fat. If preserving texture and appearance is critical, opt for lower-fat varieties like mozzarella or fresh goat cheese, which freeze more gracefully. For high-fat cheeses, prioritize usage in cooked dishes post-thawing, and accept that their role in your kitchen may shift from centerpiece to ingredient. With strategic handling and realistic expectations, you can minimize waste and maximize utility.

Should You Unwrap Cheese Before Bringing It to Room Temperature?

You may want to see also

Shelf Life Extension: Freezing prolongs cheese life but risks quality degradation over extended storage periods

Freezing high-temperature cheese, such as pasteurized or processed varieties, can significantly extend its shelf life, often adding months to its usability. This method is particularly beneficial for bulk purchases or seasonal surpluses, as it halts microbial growth and enzymatic activity, the primary drivers of spoilage. For instance, cheddar or mozzarella stored at 0°F (-18°C) can remain safe for up to 6 months, compared to 3–4 weeks in a refrigerator. However, this preservation comes with a caveat: prolonged freezing risks altering texture, flavor, and moisture content, potentially rendering the cheese less desirable for its intended use.

The science behind freezing’s impact lies in its disruption of cheese’s microstructure. High-temperature cheeses, often heat-treated to improve meltability and stability, contain proteins and fats that can separate when frozen and thawed. Ice crystals form during freezing, puncturing cell walls and releasing moisture upon thawing, leading to a crumbly or grainy texture. For example, shredded high-temperature cheese, commonly used in pizzas or sauces, may clump together or lose its ability to melt smoothly after freezing. To mitigate this, wrap the cheese tightly in heavy-duty aluminum foil or vacuum-sealed bags to minimize air exposure and moisture loss.

While freezing is a practical solution for short-term storage, it’s not a one-size-fits-all approach. Hard cheeses like Parmesan fare better than soft, high-moisture varieties like fresh mozzarella, which can become mealy or rubbery. For optimal results, freeze cheese in portions suited to single uses, as repeated thawing and refreezing accelerates quality degradation. Label packages with the freezing date and consume within 2–3 months for best results. If using frozen cheese for cooking, incorporate it directly into dishes without thawing to preserve texture and flavor.

The trade-off between extended shelf life and potential quality loss raises the question: when is freezing worth it? For high-temperature cheeses destined for cooking or melting, freezing remains a viable option, as minor textural changes are less noticeable in dishes like casseroles or grilled sandwiches. However, for cheeses intended for snacking or pairing with wine, freezing may compromise the sensory experience. Consider the end use before freezing and prioritize refrigeration for shorter-term storage when possible. Ultimately, freezing is a tool to balance convenience and quality, not a guarantee of indefinite preservation.

Unrefrigerated Tostitos Cheese: Risks, Spoilage, and Safety Concerns Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

High-temperature cheese, such as mozzarella or cheddar, undergoes changes in texture and moisture distribution when frozen. The water content expands into ice crystals, which can disrupt the protein matrix, leading to a grainy or crumbly texture upon thawing.

While high-temperature cheese can be frozen, it often loses some quality. Freezing can cause separation of fat and moisture, resulting in a less creamy texture and altered flavor. Proper wrapping and quick freezing can minimize these effects.

High-temperature cheese can be stored in the freezer for up to 6 months. Beyond this, it may develop freezer burn or further degradation in texture and taste, though it remains safe to eat.

Yes, freezing can affect the melting properties of high-temperature cheese. The formation of ice crystals can alter the protein structure, making the cheese less stretchy or smooth when melted after thawing.

High-temperature cheese should be thawed slowly in the refrigerator to minimize texture changes. Avoid thawing at room temperature or using a microwave, as this can accelerate moisture loss and further degrade the cheese's quality.