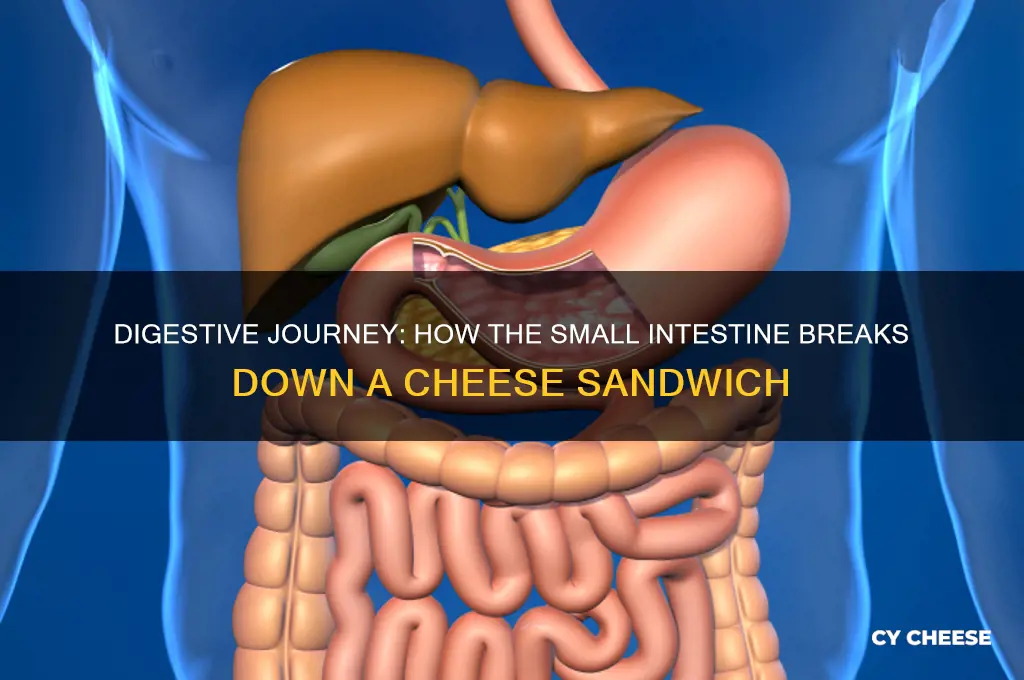

When a cheese sandwich reaches the small intestine, the process of digestion intensifies as this organ plays a crucial role in breaking down food into absorbable nutrients. The sandwich's components—bread, cheese, and any additional ingredients—are already partially digested by enzymes from the saliva and stomach. In the small intestine, pancreatic enzymes further break down carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, while bile from the liver emulsifies fats, making them easier to digest. The intestinal lining, lined with tiny finger-like projections called villi, absorbs these nutrients into the bloodstream, ensuring they can be used by the body for energy, growth, and repair. This highly efficient system ensures that the cheese sandwich is transformed from a meal into essential building blocks for the body's functions.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Digestion Begins | Mechanical breakdown by muscular contractions (peristalsis) and chemical breakdown by enzymes. |

| Enzymatic Action | Pancreatic enzymes (amylase, lipase, proteases) and intestinal enzymes (disaccharidases, peptidases) break down carbohydrates, fats, and proteins into simpler molecules. |

| Carbohydrate Digestion | Starch from bread is broken down into maltose by amylase, then further into glucose by disaccharidases. |

| Protein Digestion | Proteins from cheese and bread are broken down into amino acids by proteases like trypsin and chymotrypsin. |

| Fat Digestion | Fats from cheese are emulsified by bile salts, then broken down into fatty acids and glycerol by lipase. |

| Absorption | Simple sugars (glucose), amino acids, fatty acids, glycerol, vitamins, and minerals are absorbed through the intestinal lining into the bloodstream. |

| Water Absorption | Water is absorbed along with nutrients, helping to form a semi-solid chyme. |

| Microbial Activity | Some undigested carbohydrates (like resistant starch) may be fermented by gut bacteria, producing gases and short-chain fatty acids. |

| Movement | Peristalsis moves the partially digested food (chyme) through the small intestine toward the large intestine. |

| Duration | The entire process takes approximately 3-6 hours, depending on individual factors. |

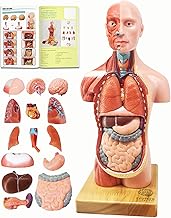

Explore related products

$59.99

What You'll Learn

- Enzyme Breakdown: Digestive enzymes break down proteins, fats, and carbs in the sandwich

- Nutrient Absorption: Nutrients like amino acids, fatty acids, and sugars are absorbed

- Role of Bile: Bile emulsifies fats, aiding in their digestion and absorption

- Villus Function: Intestinal villi increase surface area for efficient nutrient absorption

- Waste Formation: Undigested components move to the large intestine as waste

Enzyme Breakdown: Digestive enzymes break down proteins, fats, and carbs in the sandwich

Digestive enzymes are the unsung heroes of nutrient extraction, and their role in breaking down a cheese sandwich in the small intestine is a marvel of biochemical precision. Proteins, fats, and carbohydrates—the macronutrients in your sandwich—are too complex to be absorbed directly. Enter the enzymes: pepsin, trypsin, and chymotrypsin dismantle proteins into amino acids; lipase breaks down fats into fatty acids and glycerol; and amylase, along with other carbohydrases, converts carbs into simple sugars. This orchestrated breakdown transforms your meal into a molecular feast the body can use.

Consider the process as a culinary deconstruction, but instead of creating art, it fuels life. For instance, the cheese in your sandwich is rich in casein, a protein that requires specific enzymes to unravel its structure. Without sufficient proteases, this protein would pass through the digestive tract largely intact, depriving you of essential amino acids. Similarly, the bread’s starches rely on amylase to become glucose, a vital energy source. Understanding this mechanism highlights why enzyme deficiencies, such as lactose intolerance or pancreatic insufficiency, can turn a simple sandwich into a digestive challenge.

To optimize enzyme function, timing and conditions matter. The small intestine’s slightly alkaline environment (pH 7-9) activates enzymes like trypsin and lipase, while acidic chyme from the stomach signals the pancreas to release bicarbonate, neutralizing acidity. Practical tips include pairing enzyme-rich foods like pineapple (bromelain) or papaya (papain) with protein-heavy meals to aid digestion. For those with enzyme deficiencies, over-the-counter supplements like alpha-galactosidase (for gas reduction) or lactase (for dairy digestion) can be taken 5-10 minutes before eating, following dosage guidelines (typically 1-2 capsules per meal).

Comparing this process to industrial machinery reveals its efficiency. Just as a factory breaks raw materials into usable components, digestive enzymes disassemble food into nutrients with minimal waste. However, unlike machines, enzymes are highly specific, each targeting a particular substrate. This specificity ensures that proteins, fats, and carbs are broken down simultaneously but independently, preventing metabolic bottlenecks. For older adults or those with chronic conditions, this system may slow down, necessitating dietary adjustments like smaller, more frequent meals or enzyme supplementation under medical guidance.

In conclusion, enzyme breakdown in the small intestine is a testament to the body’s ingenuity. By understanding this process, you can make informed choices to support digestion—whether through mindful eating, strategic food pairing, or targeted supplementation. After all, a cheese sandwich isn’t just a meal; it’s a lesson in biochemistry, one bite at a time.

Mastering Propane Smoker Techniques: Perfectly Smoking Cheese at Home

You may want to see also

Nutrient Absorption: Nutrients like amino acids, fatty acids, and sugars are absorbed

The small intestine is a bustling hub of nutrient extraction, where the remnants of your cheese sandwich undergo a meticulous breakdown and absorption process. Here, the body's focus shifts from mechanical digestion to a chemical symphony, ensuring that every morsel of nutrition is captured. This is where the true magic happens, transforming your lunch into fuel for your body.

Amino Acids: Building Blocks of Protein

Imagine the cheese and bread proteins as intricate chains, ready to be dismantled. Enzymes like aminopeptidase and dipeptidases, secreted by the intestinal walls, act as skilled workers, breaking these chains into individual amino acids. This process is crucial, as amino acids are the body's building blocks for muscles, enzymes, and hormones. For instance, the cheese's casein protein is rich in glutamine, an amino acid vital for gut health, especially in children and the elderly, where it supports immune function and intestinal integrity. The absorption of these amino acids is a rapid process, with the body efficiently utilizing them for growth, repair, and energy production.

Fatty Acid Journey: From Triglycerides to Energy

The fats in your sandwich, primarily triglycerides, undergo a transformation. Bile salts, released from the liver, emulsify these fats, breaking them into smaller droplets. This increases the surface area for enzyme action. Pancreatic lipase then steps in, converting triglycerides into fatty acids and monoglycerides. These smaller molecules can now be absorbed through the intestinal lining. Interestingly, the absorption rate of fatty acids is influenced by the type of fat. For instance, medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs), found in small amounts in dairy, are absorbed directly into the portal circulation, providing a quick energy source, especially beneficial for athletes or those with fat malabsorption issues.

Sugar Rush: Carbohydrate Breakdown

Carbohydrates, primarily from the bread, are broken down into simple sugars like glucose and fructose. Enzymes such as sucrase, lactase, and maltase line the intestinal walls, ensuring these sugars are in their most basic form for absorption. This process is vital for energy production, especially for the brain, which relies heavily on glucose. The absorption of these sugars is tightly regulated, with the body maintaining blood sugar levels through hormonal signals. For individuals with lactose intolerance, the lack of lactase enzyme means undigested lactose can cause discomfort, highlighting the importance of enzyme function in nutrient absorption.

In the small intestine, the cheese sandwich's nutrients are not just absorbed but meticulously processed, ensuring the body receives the maximum benefit. This intricate dance of enzymes and molecules is a testament to the body's efficiency in extracting what it needs. Understanding this process can guide dietary choices, especially for those with specific nutritional requirements or digestive challenges. For instance, pairing certain foods can enhance nutrient absorption; vitamin C-rich foods can improve iron absorption, a useful tip for those at risk of anemia. The small intestine's role is not just digestion but a sophisticated nutrient extraction system, tailored to meet the body's diverse needs.

Exploring the Growing Number of Non-Dairy Cheese Brands in the US

You may want to see also

Role of Bile: Bile emulsifies fats, aiding in their digestion and absorption

Bile, a greenish-yellow fluid produced by the liver, plays a pivotal role in the digestion of fats from a cheese sandwich in the small intestine. When you consume a cheese sandwich, the fats within it—primarily triglycerides—are large and hydrophobic, making them difficult to break down. Bile steps in as a critical agent, acting like a detergent to emulsify these fats. This process breaks down large fat globules into smaller droplets, dramatically increasing their surface area. The result? Pancreatic lipase, the enzyme responsible for fat digestion, can now access and act upon these fats more efficiently, converting them into fatty acids and monoglycerides.

Consider this analogy: emulsification by bile is akin to using dish soap on greasy plates. Just as soap breaks down grease into smaller particles that can be washed away, bile transforms fats into a form that can be absorbed by the body. Without bile, the fats in your cheese sandwich would remain largely undigested, leading to malabsorption and potential deficiencies in fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K). This is why individuals with bile duct obstructions or liver diseases often experience steatorrhea, a condition characterized by fatty, foul-smelling stools.

The process of emulsification is not just mechanical; it’s also strategic. Bile is stored in the gallbladder and released into the duodenum (the first part of the small intestine) in response to the presence of fats. The amount of bile released is proportional to the fat content of the meal. For instance, a cheese sandwich, rich in saturated fats, triggers a substantial bile release. However, excessive fat intake can overwhelm the system, leading to incomplete digestion and discomfort. A practical tip: pair high-fat meals with fiber-rich foods to slow digestion and allow bile to work more effectively.

From a comparative standpoint, bile’s role in fat digestion is unique. While other digestive enzymes target specific substrates (e.g., amylase for carbohydrates, proteases for proteins), bile acts as a facilitator, enhancing the efficacy of lipase. This distinction underscores its importance in the digestive cascade. For those with compromised bile production, such as individuals post-cholecystectomy (gallbladder removal), supplemental bile salts may be prescribed to aid fat digestion. Dosage typically ranges from 300 to 500 mg per meal, though this should be tailored by a healthcare provider.

In conclusion, bile’s emulsifying action is indispensable for breaking down the fats in a cheese sandwich, ensuring they can be digested and absorbed. Its role is both mechanical and strategic, responding to dietary fat content and enabling the work of other enzymes. Understanding this process highlights the importance of liver and gallbladder health in maintaining optimal digestion. Whether you’re enjoying a hearty cheese sandwich or managing a fat-related digestive condition, bile’s function is a cornerstone of nutritional well-being.

Mascarpone Cheese Measurement Guide: Grams in a Tablespoon

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$12.97 $15.97

Villus Function: Intestinal villi increase surface area for efficient nutrient absorption

The small intestine is a marvel of biological engineering, and its efficiency in nutrient absorption hinges on a microscopic feature: the intestinal villi. These tiny, finger-like projections line the inner surface of the small intestine, dramatically increasing its absorptive area. To put this into perspective, the villi expand the intestinal surface area from about 2 square meters to roughly 250 square meters—equivalent to the size of a tennis court. This vast surface area is crucial for extracting nutrients from a cheese sandwich or any other meal, ensuring the body receives the energy and building blocks it needs.

Consider the journey of a cheese sandwich as it enters the small intestine. The sandwich’s components—bread, cheese, and any accompanying ingredients—have been broken down by enzymes in the mouth and stomach. By the time this mixture, now called chyme, reaches the small intestine, it’s a semi-liquid slurry. Here, the villi spring into action. Each villus is covered in microvilli, further amplifying the surface area. This intricate structure allows for rapid and efficient absorption of nutrients like carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. For instance, the lactose and protein from cheese are absorbed through the villi, while the starch from bread is broken down into glucose and absorbed into the bloodstream.

The function of villi isn’t just about surface area—it’s also about speed and specificity. Villi contain specialized cells called enterocytes, which transport nutrients across the intestinal wall and into the bloodstream or lymphatic system. For example, fats from the cheese sandwich are absorbed via lacteals, part of the lymphatic system, while other nutrients like amino acids and glucose are directly absorbed into the bloodstream. This dual pathway ensures that even large meals, like a hearty cheese sandwich, are processed efficiently. Without villi, nutrient absorption would be sluggish, leading to malnutrition despite adequate food intake.

Practical implications of villus function extend to dietary choices and health conditions. For optimal nutrient absorption, pair foods rich in fat (like cheese) with sources of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) to enhance their uptake. However, conditions like celiac disease or Crohn’s disease can damage villi, impairing absorption. For example, a person with celiac disease consuming gluten (found in bread) experiences villus atrophy, reducing the surface area for nutrient absorption. In such cases, a gluten-free diet is essential to allow villi to regenerate. Monitoring symptoms like bloating, diarrhea, or unexplained weight loss can signal villus dysfunction, warranting medical evaluation.

In summary, intestinal villi are the unsung heroes of digestion, transforming a simple cheese sandwich into fuel for the body. Their role in increasing surface area and facilitating nutrient absorption underscores the importance of gut health. Whether you’re enjoying a meal or managing a digestive condition, understanding villus function offers actionable insights into optimizing nutrition and well-being.

Mastering the Art of Smoking Cheese in Your Little Chief Smoker

You may want to see also

Waste Formation: Undigested components move to the large intestine as waste

Not all components of a cheese sandwich are fully digested in the small intestine. While enzymes break down carbohydrates, proteins, and fats into absorbable nutrients, certain elements resist this process. For instance, cellulose from whole-grain bread and lactose from cheese (if you’re intolerant) remain intact. These undigested particles, along with fiber, continue their journey through the digestive tract, propelled by muscular contractions called peristalsis.

The small intestine acts as a selective gatekeeper, absorbing what it can and passing the rest along. This sorting process is crucial for nutrient extraction but also ensures that waste material doesn’t linger, which could lead to fermentation or discomfort. For example, undigested lactose reaches the large intestine, where it may cause bloating or gas in lactose-intolerant individuals. Understanding this mechanism highlights the importance of dietary choices, especially for those with specific intolerances or sensitivities.

Once in the large intestine, undigested components undergo further processing. Bacteria ferment fiber and resistant starches, producing gases like methane and carbon dioxide, as well as short-chain fatty acids that nourish colon cells. This microbial activity is essential for gut health but can also contribute to flatulence or abdominal distension. Staying hydrated and gradually increasing fiber intake can mitigate these effects, allowing the colon to function more efficiently.

The final stage of waste formation involves water absorption and compaction. The large intestine reabsorbs approximately 90% of the water from indigestible material, transforming it into solid stool. This process is influenced by factors like hydration levels and gut motility. For optimal waste elimination, adults should aim for 25–30 grams of fiber daily, paired with adequate water intake (about 3 liters for men and 2.7 liters for women). Ignoring these guidelines can lead to constipation or incomplete evacuation, underscoring the interconnectedness of digestion and waste management.

In summary, waste formation from a cheese sandwich’s undigested components is a natural, multi-step process that relies on the small intestine’s efficiency and the large intestine’s microbial and absorptive functions. By understanding this journey, individuals can make informed dietary choices to support digestive health and minimize discomfort. Whether it’s opting for lactose-free cheese or pairing meals with fiber-rich sides, small adjustments can significantly impact how the body processes and eliminates what it cannot use.

Leaving Cheese Out Overnight: Does It Hurt or Help?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

In the small intestine, the cheese sandwich is further broken down by digestive enzymes and bile. Carbohydrates (like bread) are broken into sugars, proteins (like cheese) into amino acids, and fats into fatty acids and glycerol.

The small intestine absorbs nutrients through its lining, which contains tiny finger-like structures called villi. Sugars, amino acids, and fatty acids from the cheese sandwich are transported into the bloodstream via these villi.

Enzymes like amylase, protease, and lipase break down carbohydrates, proteins, and fats from the cheese sandwich, respectively. These enzymes are secreted by the pancreas and intestinal lining to aid digestion.

The small intestine does not fully digest fiber from the bread in a cheese sandwich. Instead, fiber passes through the small intestine largely unchanged and moves into the large intestine, where it supports gut health and bowel movements.