Blue cheese is known for its distinct appearance and strong flavour, but what exactly are those blue bits? The blue or blue-green veins are actually mould, specifically Penicillium roqueforti, which is added during the production process. This is different from the mould that can grow on food in your fridge. While the idea of eating mould may be off-putting to some, it is perfectly safe to consume and gives blue cheese its unique taste.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Colour | Blue/Green |

| Type | Mould |

| Genus | Penicillium |

| Species | Penicillium roqueforti |

| Taste | Strong |

| Allergy | May cause allergic reaction if allergic to penicillin |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Blue cheese is made using the mould Penicillium roqueforti

- Blue cheese is created in a two-phase process, starting with culturing spore-rich inocula

- The mould is added to the curds via sprinkling or piercing

- Blue cheese has a strong taste, with a difference in flavour between the white and blue parts

- Blue cheese is healthy, but those allergic to penicillin should avoid it

Blue cheese is made using the mould Penicillium roqueforti

Nowadays, the process of making blue cheese is extremely controlled and intentional. The main method of making blue cheese is a piercing method, in which stainless steel needles create crevices in the cheese to allow oxygen to interact with the cultures and for the blue mould to grow from within. The mould itself is from one or more strains of the genus Penicillium.

To make blue cheese on a commercial scale, the first phase involves preparing a Penicillium roqueforti inoculum. This is done by washing the mould from a pure culture agar plate, freezing it, and then freeze-drying it. This process retains the value of the culture, and it can be activated later by adding water.

In the next phase, salt, sugar, or both are added to autoclaved, homogenised milk via a sterile solution. This mixture is then inoculated with the Penicillium roqueforti inoculum and incubated for three to four days at 21–25 °C (70–77 °F). More salt and/or sugar is added, and aerobic incubation continues for another one to two days. Alternatively, sterilised, homogenised milk and reconstituted non-fat solids or whey solids can be mixed with sterile salt to create a fermentation medium, to which a spore-rich Penicillium roqueforti culture is added.

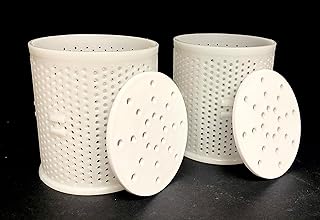

Finally, after the curds have been ladled into containers and formed into cheese loaves, the Penicillium roqueforti inoculum is sprinkled on top along with Brevibacterium linens. The curds are then knit in moulds, and whey drainage is continued for 10–48 hours without applying any pressure. Salt is added to provide flavour and act as a preservative, and the cheese is then aged for 60–90 days to ripen and develop its characteristic flavour.

Gluten-Free Diet: Kraft Roka Blue Cheese Dressing

You may want to see also

Blue cheese is created in a two-phase process, starting with culturing spore-rich inocula

Salt, sugar, or both are then added to autoclaved, homogenized milk via a sterile solution. This mixture is then inoculated with Penicillium roqueforti and incubated for three to four days at 21-25°C (70-77°F). More salt and/or sugar is added, and aerobic incubation is continued for an additional one to two days. Alternatively, sterilized, homogenized milk and reconstituted non-fat solids or whey solids are mixed with sterile salt to create a fermentation medium. A spore-rich Penicillium roqueforti culture is then added, followed by modified milk fat.

During the ripening process, the temperature and humidity in the room where the cheese is aging are monitored to ensure the cheese does not spoil and maintains its optimal flavor and texture. The ripening temperature is generally around eight to ten degrees Celsius, with a relative humidity of 85-95%. At the beginning of this process, the cheese loaves are punctured to create small openings for air to penetrate and support the growth of aerobic Penicillium roqueforti cultures, thus encouraging the formation of blue veins.

The distinctive flavor and aroma of blue cheese come from methyl ketones, which are metabolic products of Penicillium roqueforti. Blue cheese is believed to have been discovered by accident when cheeses were stored in caves with naturally controlled temperatures and moisture levels, creating favorable environments for harmless molds.

Blue Cheese Wheels: Massive, Mature, and Magnificent

You may want to see also

The mould is added to the curds via sprinkling or piercing

The blue veins in blue cheese are a type of mould called Penicillium roqueforti. This is not the same strain as the antibiotic penicillin, despite the similar names. The mould is added to the curds via sprinkling or piercing. Piercing is the main method of making blue cheese. The cheese starts as a simple-looking white wheel, which is then pierced with stainless steel needles. These needles create crevices to allow oxygen to interact with the cultures in the cheese, enabling the blue mould to grow from within.

Sprinkling the mould onto the curds is another method of making blue cheese. After the curds have been ladled into containers to drain and form into a wheel of cheese, the Penicillium roqueforti inoculum is sprinkled on top of the curds along with Brevibacterium linens. The curds are then formed into cheese loaves with a relatively open texture. The mould needs oxygen to grow, so the cheese moulds are inverted frequently during the whey drainage process, which takes 10-48 hours.

The mould is added to the cheese during the culturing phase of production. First, a Penicillium roqueforti inoculum is prepared. This involves washing the mould from a pure culture agar plate, freezing it, and then freeze-drying it. This process retains the value of the culture, and it is reactivated when water is added. All methods of making blue cheese involve the use of a freeze-dried Penicillium roqueforti culture.

Blue Cheese's Perfect Herb Partners: A Culinary Adventure

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Blue cheese has a strong taste, with a difference in flavour between the white and blue parts

Blue cheese is characterised by its strong taste and the difference in flavour between its white and blue parts. The blue veins in blue cheese are the result of controlled and intentional processes involving piercing methods or direct injection with Penicillium roqueforti inoculum. The mould itself belongs to the genus Penicillium, specifically Penicillium roqueforti, which is commercially manufactured and added during the production process.

The distinct flavour of blue cheese is developed through a fermentation period, typically lasting 60 to 90 days. During this time, the interaction between the cheese, mould, and oxygen results in the formation of blue veins, contributing to the unique taste profile. The white parts of the cheese, devoid of the blue mould, offer a milder flavour compared to the blue sections.

The process of making blue cheese involves multiple steps, including curdling, drainage, and moulding, followed by the addition of salt for flavour enhancement and preservation. The final step is ripening the cheese through ageing, which further develops the characteristic blue cheese flavour.

The difference in flavour between the white and blue parts of blue cheese is due to the presence of mould in the latter. The blue mould, often appearing blue or green, adds a strong and unique taste to the cheese. While some people enjoy the "funk and bite" of blue cheese, others may find it unappealing due to its distinct appearance and flavour.

It is important to note that the blue mould in cheese is different from the blue spoilage mould that may be found in refrigerators. Additionally, those allergic to penicillin should avoid consuming blue cheese as the mould is related to the antibiotic.

Pumpkin and Blue Cheese: A Match Made in Heaven?

You may want to see also

Blue cheese is healthy, but those allergic to penicillin should avoid it

Blue cheese is a popular cheese variety globally, known for its strong flavour and pungent smell. It is also recognised for its health benefits, such as being rich in calcium, which promotes bone health and helps prevent osteoporosis. Blue cheese also contains phosphorus, essential for strong teeth and bones, and a compound called spermidine, which may reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease. It is also a great source of protein, especially for those who are lactose intolerant.

However, blue cheese is also high in fat, sodium, and calories, so it should be consumed in moderation. Those with high cholesterol, blood pressure, renal, or water retention issues should be cautious about including blue cheese in their diet due to its high sodium content.

The blue veins in blue cheese are the result of the Penicillium Roqueforti bacteria, which is added during the ripening process. Small holes are made in the cheese surface, allowing the bacteria to grow and produce the characteristic blue veins.

The same type of mould used to make the antibiotic penicillin is also used in blue cheese. This has led to the common misconception that those allergic to penicillin should avoid blue cheese. While those with a penicillin allergy should be cautious, the strain of mould used in blue cheese is typically different from that used in penicillin production. The mould in blue cheese is usually Penicillium Roqueforti, while the antibiotic uses Penicillium chrysogenum. However, some blue cheeses may use the chrysogenum strain, so it is essential to check the label and consult a medical professional before consuming blue cheese if you have a penicillin allergy.

Blu Cheese and Tyramine: What's the Connection?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The blue bits in blue cheese are a type of mold called Penicillium roqueforti.

Yes, blue mold is safe to eat. In fact, it's healthy! It's the same type of mold that's used to treat diabetes. However, if you're allergic to penicillin, it's best to avoid blue cheese.

The blue mold is added to the cheese through a piercing method. The cheesemakers use stainless steel needles to create crevices in the cheese, allowing oxygen to interact with the cultures in the cheese and the blue mold to grow from within.