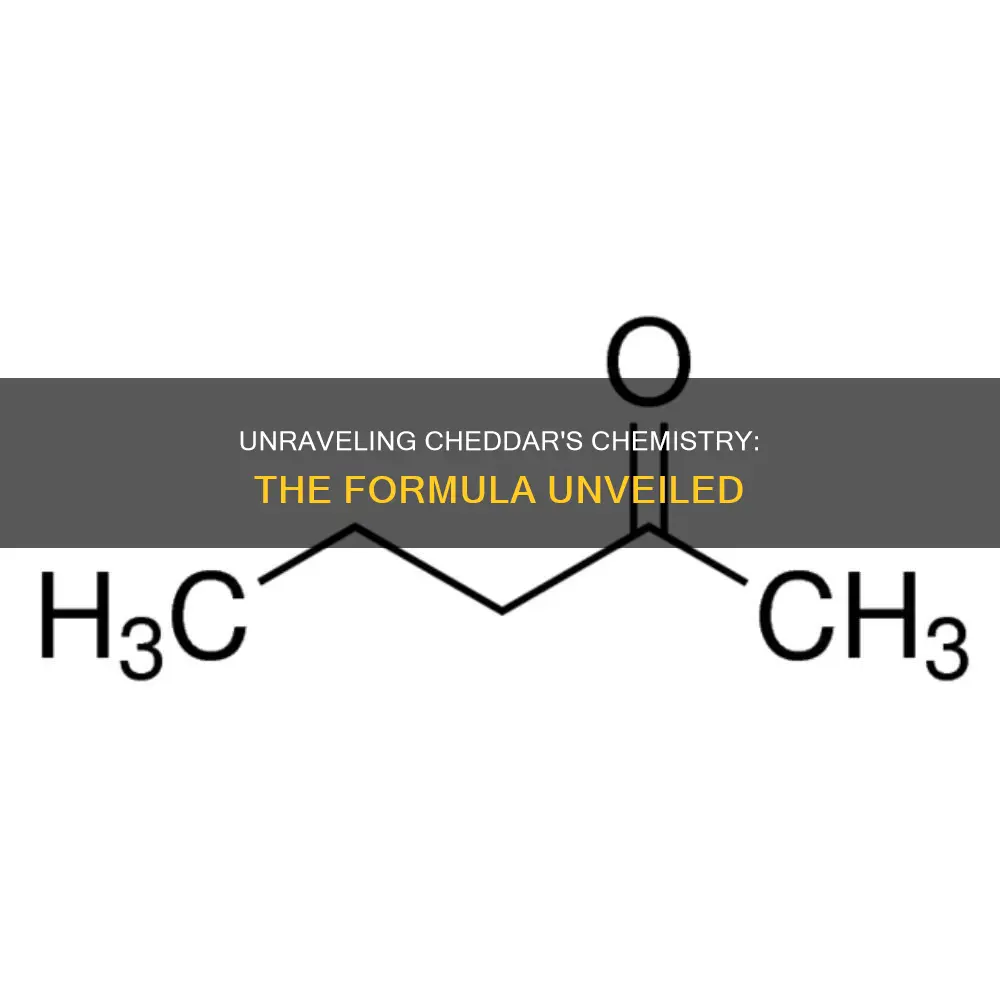

Cheddar cheese, a beloved dairy product, has a unique chemical composition that contributes to its distinct flavor and texture. Understanding the chemical formula for cheddar can provide insights into its production and characteristics. The primary components of cheddar cheese include proteins, fats, and lactose, with the most abundant protein being casein. The chemical formula for casein, the main protein in cheddar, is typically represented as C46H78N12O18, reflecting its complex structure. This formula highlights the intricate arrangement of atoms that form the building blocks of cheddar's protein matrix.

What You'll Learn

- Milk Composition: Cheddar's unique formula is derived from milk's proteins and fats

- Fermentation Process: Bacteria cultures convert lactose into lactic acid, a key cheddar ingredient

- Coagulation: Enzymes curdle milk, forming a gel, essential for cheddar's texture

- Aging: Ripening transforms flavor and texture, a crucial cheddar-making step

- Fat Content: Cheddar's fat percentage influences flavor, moisture, and melting properties

Milk Composition: Cheddar's unique formula is derived from milk's proteins and fats

Cheddar cheese, a beloved dairy product with a rich history, owes its unique characteristics to the composition of milk, primarily its proteins and fats. Milk, a complex liquid, contains a myriad of components that contribute to the final flavor, texture, and appearance of cheddar. The proteins and fats in milk are the key players in the transformation of this liquid into a solid, flavorful cheese.

Milk proteins, such as casein and whey proteins, are essential in the cheese-making process. Casein, a phosphoprotein, is responsible for the formation of a gel-like structure when milk is curdled. This process, known as coagulation, is crucial for the development of cheddar's distinctive texture. The casein micelles, when agitated, form a stable network that traps water and other milk components, contributing to the cheese's moisture content and texture. Whey proteins, on the other hand, are less abundant in cheddar and are often separated during the cheese-making process, leaving behind a more concentrated casein-rich curd.

Fats in milk, primarily in the form of butterfat, also play a significant role in cheddar's unique formula. Butterfat is a complex mixture of fatty acids and glycerol. During the cheese-making process, the fat globules in milk are broken down and re-emulsified, contributing to the final fat content of the cheese. Cheddar's distinctive flavor and creamy texture are partly due to the careful control of fat content and the specific fat composition, which can vary depending on the milk source and processing methods.

The transformation of milk into cheddar involves a series of intricate steps. Milk is curdled using bacterial cultures or rennet, which causes the casein to coagulate and separate from the whey. The curd is then cut into small cubes and gently stirred to release more whey. This process, known as cutting and stirring, is crucial for developing the desired texture and flavor. The curds are then heated and stirred again, a process called cooking, which further transforms the proteins and fats, leading to the formation of cheddar's characteristic flavor and texture.

In summary, the chemical formula for cheddar cheese is a result of the intricate interplay between milk's proteins and fats. The coagulation of casein proteins creates a stable structure, while the breakdown and re-emulsification of fat globules contribute to the cheese's fat content and texture. The specific processes involved in cheddar's production, such as curdling, cutting, stirring, and cooking, further refine the milk's components, resulting in a cheese with a unique flavor, texture, and appearance. Understanding the milk composition is key to appreciating the art and science behind this beloved dairy product.

Popcorn Cheddar Cheese: A Tasty Snack or a Culinary Conundrum?

You may want to see also

Fermentation Process: Bacteria cultures convert lactose into lactic acid, a key cheddar ingredient

The fermentation process in the making of cheddar cheese is a fascinating interplay of bacteria and chemistry. At its core, this process involves the conversion of lactose, a natural sugar found in milk, into lactic acid by specific bacterial cultures. These bacteria are carefully selected and cultivated to ensure they thrive in the unique environment of cheese production.

When milk is curdled and the curds are cut and stirred, the bacteria cultures are introduced. These cultures consist of various strains, each playing a unique role. One of the primary bacteria involved is Lactobacillus, a group of lactic acid bacteria. These bacteria are the key players in the fermentation process, as they possess the enzyme lactase, which breaks down lactose into glucose and galactose. This breakdown is crucial as it initiates the subsequent reactions.

As the lactose is converted, the bacteria also produce lactic acid as a byproduct. This lactic acid is a critical component of cheddar cheese, contributing to its characteristic tangy flavor and smooth texture. The process is carefully controlled to ensure the bacteria cultures remain active and efficient throughout the cheese-making journey. The optimal pH level and temperature are maintained to create an environment conducive to bacterial growth and activity.

The fermentation process is a delicate balance of art and science. It requires precise control over various factors, including temperature, pH, and the addition of specific nutrients to support bacterial growth. This intricate dance of bacteria and chemistry transforms the milk into a semi-solid mass, with the lactose conversion playing a pivotal role. The lactic acid produced not only contributes to flavor but also aids in the development of the cheese's structure, making it firm and creamy.

Understanding this fermentation process is essential for cheese makers, as it directly influences the flavor, texture, and overall quality of cheddar cheese. The careful selection and management of bacterial cultures ensure that the cheese meets the desired standards, providing consumers with a delicious and consistent product. This process is a testament to the intricate relationship between biology and food science.

Trader Joe's Unexpected Cheddar: Is It Vegan-Friendly?

You may want to see also

Coagulation: Enzymes curdle milk, forming a gel, essential for cheddar's texture

The process of making cheddar cheese involves a crucial step known as coagulation, which is primarily driven by enzymes. These enzymes play a vital role in transforming liquid milk into a gel-like substance, a key factor in achieving the characteristic texture of cheddar cheese.

Coagulation is a complex biochemical reaction that occurs when specific enzymes, such as rennet or bacterial proteases, are added to milk. These enzymes have the unique ability to break down the milk proteins, casein, into smaller fragments. The primary target of these enzymes is the phospholipid bilayer that surrounds the casein micelles, which are the primary components of milk. When the enzymes bind to this bilayer, they initiate a series of reactions that lead to the formation of a gel.

The mechanism begins with the enzyme's action on the milk proteins, causing them to denature and aggregate. This aggregation results in the formation of a solid mass, which then sets and forms a gel-like structure. This gel is essential for the texture and structure of cheddar cheese, as it provides the necessary body and mouthfeel. The process is carefully controlled to ensure the desired consistency, as too much enzyme activity can lead to an overly firm texture, while too little may result in a runny product.

The enzymes used in cheese-making are highly specific and efficient. For instance, rennet, a traditional enzyme source, contains a protease that specifically targets the milk proteins. Bacterial proteases, on the other hand, are often used in modern cheese-making processes due to their consistency and ease of use. These enzymes are carefully measured and added to the milk at precise temperatures and times to optimize the coagulation process.

Understanding coagulation and the role of enzymes is fundamental to the art of cheese-making. It allows artisans and scientists to manipulate the process, creating a wide variety of cheeses with different textures and flavors. The control of coagulation is a delicate balance, and the result is a delicious, textured cheddar cheese that we all enjoy.

Chex Mix's Cheddar Triangle Mystery: A Tasty Treat Unveiled

You may want to see also

Aging: Ripening transforms flavor and texture, a crucial cheddar-making step

The aging or ripening process is a critical phase in the production of cheddar cheese, significantly impacting its flavor, texture, and overall quality. This step involves the controlled transformation of the cheese over an extended period, typically ranging from several weeks to months. During this time, the cheese undergoes a series of chemical and biological changes that contribute to its unique characteristics.

As the cheese ages, the bacteria and enzymes present in the milk continue their work, breaking down the milk proteins and fats. This process is responsible for the development of flavor and texture. The breakdown of proteins, for instance, leads to the formation of amino acids, which contribute to the savory taste of cheddar. Simultaneously, the fats in the cheese undergo changes, becoming more spreadable and contributing to the creamy texture that cheddar is known for.

One of the key aspects of aging is the development of flavor compounds. As the cheese matures, it develops a rich, complex flavor profile. This is achieved through the action of specific bacteria and enzymes. For example, the bacterium *Penicillium* produces enzymes that break down milk proteins, releasing amino acids and contributing to the cheese's umami taste. Additionally, the breakdown of fats produces volatile compounds, such as butyric acid, which adds a characteristic pungent note to cheddar.

Texture also undergoes a remarkable transformation during aging. Initially, the cheese has a soft, fresh consistency. However, as it ages, the proteins and fats undergo further modifications, leading to a harder, more compact structure. This change in texture is due to the cross-linking of proteins, which makes the cheese more resilient and less likely to crumble. The aging process also contributes to the formation of small, open eyes on the cheese's surface, which are characteristic of well-aged cheddar.

The duration and conditions of aging can vary depending on the desired type of cheddar. Younger cheddars, aged for a few weeks, are often used for slicing and have a milder flavor and softer texture. In contrast, older cheddars, aged for several months, exhibit a stronger flavor, a harder texture, and a more pronounced aroma. The aging process is a delicate balance of art and science, requiring careful monitoring of temperature, humidity, and microbial activity to ensure the desired outcome.

Exploring Cheddar's Natural Curdling: Is It Rennet-Free?

You may want to see also

Fat Content: Cheddar's fat percentage influences flavor, moisture, and melting properties

The fat content in cheddar cheese is a crucial factor that significantly impacts its flavor, texture, and overall quality. Cheddar, a popular hard cheese, is known for its rich, savory taste, and the fat percentage plays a pivotal role in achieving this characteristic flavor profile. Higher fat content in cheddar generally leads to a more intense, buttery flavor, while lower fat versions may exhibit a milder, slightly sharper taste. This variation in flavor is primarily due to the different proportions of milk fats, such as butterfat, in the cheese-making process.

The moisture content in cheddar is also closely tied to fat percentage. Cheeses with higher fat levels tend to have a creamier texture and a higher moisture content, making them more spreadable and less likely to dry out over time. This characteristic is especially desirable in processed cheese products, where moisture retention is essential for maintaining freshness and appeal.

Melting properties are another critical aspect influenced by fat content. Cheddar with a higher fat percentage typically melts more smoothly and evenly, making it ideal for use in cooking and food preparation. This property is highly sought after in the food industry, especially for cheese-based sauces, fondue, and other dishes where a consistent melt is required. Lower-fat cheddars may exhibit a more waxy or grainy melt, which can affect their usability in certain culinary applications.

In the production of cheddar, cheesemakers carefully control the fat content to achieve the desired characteristics. The process involves adding specific amounts of cream or butterfat during curdling and aging. This technique allows for customization of the cheese's flavor, moisture, and melting properties to suit various culinary needs and consumer preferences.

Understanding the relationship between fat content and these key attributes is essential for both cheesemakers and consumers. It enables the creation of cheddar cheeses with distinct flavors and textures, catering to a wide range of applications, from gourmet cheese boards to mass-produced cheese slices. The art of crafting cheddar cheese involves a delicate balance of fat percentage, ensuring a product that meets the desired standards of taste, texture, and functionality.

Visualizing 30g of Cheddar: A Cheese Portion Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cheddar cheese, like most cheeses, is primarily composed of milk proteins and fats. The exact chemical composition can vary depending on the specific production process and ingredients used. However, a simplified representation of its main components could be:

- Proteins: Cheddar cheese contains a variety of proteins, including casein, which is a major component of milk.

- Fats: It also includes milk fats, which can be in the form of butterfat or milk fat.

- Carbohydrates: Some minor carbohydrates and lactose are present.

- Minerals: Cheddar cheese is a good source of minerals like calcium, phosphorus, and sodium.

The primary protein in cheddar cheese is casein, and its chemical formula is typically represented as:

C36H75O17N4

This formula indicates the approximate ratio of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), oxygen (O), and nitrogen (N) atoms in a single molecule of casein.

Yes, cheddar cheese contains several other important compounds:

- Lactose: A natural sugar found in milk, with the formula C12H22O11.

- Lipoproteins: These are protein-lipid complexes that help transport fats in the bloodstream.

- Enzymes: Cheddar cheese-making involves various enzymes like rennet, which aids in curdling milk.

- Minerals: As mentioned earlier, cheddar cheese is rich in minerals like calcium (Ca), phosphorus (P), and sodium (Na) in their ionic forms.