Animal rennet plays a crucial role in the traditional process of cheese making, serving as a natural enzyme complex derived primarily from the stomach lining of ruminant animals like calves, lambs, and goats. Its primary function is to coagulate milk by breaking down its proteins, specifically kappa-casein, which stabilizes milk micelles. This action causes the milk to curdle, separating it into solid curds and liquid whey. The curds are then further processed to form cheese. Animal rennet is favored for its efficiency and ability to produce a firm, smooth texture in cheeses, though it is not suitable for vegetarians, leading to the development of microbial and plant-based alternatives. Its use dates back centuries, making it a cornerstone of artisanal and traditional cheese production.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Coagulation | Animal rennet contains the enzyme chymosin, which coagulates milk by breaking down kappa-casein, a protein in milk, causing milk to curdle and form a solid mass (curd) and liquid (whey). |

| Curd Formation | It promotes the formation of a strong, elastic curd, which is essential for cheese texture and structure. |

| Whey Separation | Facilitates the separation of whey from the curd, allowing for better moisture control in the final cheese product. |

| Texture Development | Contributes to the development of a smooth, firm, and sliceable texture in hard and semi-hard cheeses. |

| Flavor Enhancement | May subtly enhance the flavor profile of certain cheeses, though its primary role is structural rather than flavor-related. |

| Efficiency | Highly efficient in small quantities, making it a preferred choice for traditional cheese making despite the availability of microbial and genetically engineered alternatives. |

| Specificity | Chymosin in animal rennet is highly specific to kappa-casein, ensuring precise and controlled curdling compared to other coagulating agents. |

| Traditional Use | Widely used in traditional cheese making for centuries, particularly in the production of cheeses like Parmesan, Cheddar, and Gruyère. |

| Source | Derived from the stomach lining of ruminant animals (e.g., calves, lambs, or goats), specifically the fourth stomach (abomasum). |

| Alternatives | Alternatives include microbial rennet (from fungi or bacteria) and genetically engineered rennet, which are often used in vegetarian or kosher/halal cheese production. |

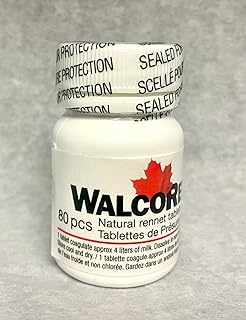

Explore related products

$14.04 $17.49

What You'll Learn

- Coagulation Process: Rennet enzymes curdle milk, separating solids (curds) from liquids (whey) in cheese making

- Curd Formation: Animal rennet ensures firm, elastic curds essential for cheese texture and structure

- Flavor Development: It contributes to unique flavors and aromas in traditional, rennet-coagulated cheeses

- Yield Efficiency: Rennet maximizes curd yield, reducing whey waste and improving cheese production efficiency

- Traditional vs. Alternatives: Animal rennet is preferred for authenticity, though microbial/plant alternatives exist

Coagulation Process: Rennet enzymes curdle milk, separating solids (curds) from liquids (whey) in cheese making

Animal rennet, derived from the stomach lining of ruminants like calves, lambs, and goats, contains a potent enzyme called chymosin. This enzyme plays a pivotal role in the coagulation process of cheese making by selectively cleaving a specific protein in milk called κ-casein. When added to milk, typically at a dosage of 0.02% to 0.05% of the milk weight, rennet initiates a cascade of events. The enzyme acts on κ-casein, destabilizing the milk’s structure and causing the casein micelles to aggregate. This aggregation transforms the liquid milk into a gel-like mass, effectively separating it into solid curds and liquid whey. The precision of rennet’s action ensures a clean break between curds and whey, which is critical for the texture and yield of the final cheese.

The coagulation process induced by rennet is highly controlled and predictable, making it a preferred choice for traditional cheese makers. Unlike acidic coagulants, which can produce a grainy texture, rennet yields a smoother, more elastic curd. This is particularly important for cheeses like Cheddar or Swiss, where curd integrity is essential for proper aging and flavor development. The enzyme’s activity is temperature-sensitive, working optimally between 30°C and 40°C (86°F to 104°F). Cheese makers must monitor this closely, as deviations can lead to weak curds or incomplete coagulation. For example, adding rennet to milk below 20°C (68°F) slows the process significantly, while temperatures above 45°C (113°F) can denature the enzyme, rendering it ineffective.

One of the most fascinating aspects of rennet’s role is its specificity. Chymosin targets only the κ-casein protein, leaving other milk components intact. This precision minimizes the risk of off-flavors or unwanted byproducts, ensuring a clean, pure cheese. However, this specificity also means that rennet must be used judiciously. Overuse can lead to overly firm curds, while underuse may result in a slow, incomplete coagulation. Cheese makers often perform a "flocculation test" to determine the optimal rennet dosage, observing how quickly a drop of rennet-treated milk forms a clot. This practical step ensures consistency across batches, a critical factor in artisanal cheese production.

For home cheese makers, understanding the coagulation process is key to success. Rennet is typically available in liquid or tablet form, with dosages adjusted based on milk volume. A common rule of thumb is to use 1/4 teaspoon of liquid rennet for every 4 liters (1 gallon) of milk. However, this can vary depending on the milk’s pH, fat content, and temperature. After adding rennet, the milk should be left undisturbed for 30 to 60 minutes, allowing the enzyme to work. Cutting the curd too early can result in a soft, rubbery texture, while waiting too long may cause the curds to become too firm. Patience and precision are paramount in this step, as they directly influence the cheese’s final quality.

In conclusion, the coagulation process driven by rennet enzymes is a delicate yet powerful transformation in cheese making. By curdling milk and separating curds from whey, rennet sets the foundation for the cheese’s texture, flavor, and structure. Its specificity, temperature sensitivity, and dosage requirements demand careful attention, but the rewards are well worth the effort. Whether crafting a hard, aged cheese or a soft, fresh variety, mastering the use of rennet is an essential skill for any cheese maker. With practice and understanding, this ancient technique continues to produce some of the world’s most beloved cheeses.

Irresistible Warm Cheese Dips to Pair Perfectly with Sourdough Bread

You may want to see also

Curd Formation: Animal rennet ensures firm, elastic curds essential for cheese texture and structure

Animal rennet is a complex of enzymes derived from the stomach lining of ruminant animals, such as calves, goats, and sheep. In cheese making, its primary role is to coagulate milk by breaking down the protein kappa-casein, which stabilizes the milk’s micelles. This enzymatic action transforms liquid milk into a solid mass of curds and whey, a critical step in cheese production. The specificity of rennet ensures a clean, efficient cut of the milk proteins, resulting in curds that are not only firm but also elastic—qualities that directly influence the final cheese’s texture and structure.

Consider the process of curd formation as a delicate balance of chemistry and craftsmanship. The dosage of animal rennet is crucial; typically, 1/8 to 1/4 teaspoon of liquid rennet is used per gallon of milk, depending on the desired cheese type. Too little rennet may yield weak, crumbly curds, while excessive amounts can lead to a bitter flavor and overly tough texture. The milk’s temperature during rennet addition is equally vital, with an optimal range of 86–104°F (30–40°C) for most cheeses. This precision ensures the enzymes work at their peak efficiency, producing curds that are both cohesive and springy.

The elasticity of curds formed with animal rennet is particularly advantageous during the cheese-making process. For example, in semi-hard cheeses like Cheddar, the curds must withstand the rigorous cutting, stirring, and pressing stages. The firmness prevents the curds from breaking apart, while the elasticity allows them to stretch and align during pressing, creating a smooth, uniform interior. Without this dual quality, the cheese might develop cracks, uneven texture, or poor meltability—undesirable traits for both artisanal and commercial cheeses.

From a comparative perspective, animal rennet outperforms many vegetarian alternatives in achieving the ideal curd structure. While microbial or plant-based coagulants can produce acceptable results, they often yield softer, less resilient curds. For cheeses requiring a robust framework, such as Parmesan or Gruyère, animal rennet remains the gold standard. Its ability to create firm, elastic curds not only enhances the cheese’s mouthfeel but also contributes to its longevity, as a well-structured cheese is less prone to drying out or crumbling prematurely.

In practice, cheese makers can optimize curd formation by monitoring the coagulation time, which typically ranges from 30 minutes to an hour with animal rennet. A simple test involves inserting a clean finger into the curd; if it splits cleanly and the whey is clear, the curds are ready for cutting. For beginners, starting with a recipe that highlights rennet’s role, such as a basic farmhouse cheddar, can provide hands-on insight into how this enzyme shapes the cheese’s final characteristics. Mastering this step ensures that the cheese not only tastes exceptional but also holds its form, slice after slice.

Cheese in the Trap: Unveiling the Actor Behind Yeong Gon

You may want to see also

Flavor Development: It contributes to unique flavors and aromas in traditional, rennet-coagulated cheeses

Animal rennet, derived from the stomach lining of ruminants, contains chymosin, an enzyme that precisely cleaves milk proteins, particularly κ-casein. This action releases para-κ-casein, a peptide known to influence flavor development in cheese. Unlike acid coagulation, which produces a sharper, more acidic profile, rennet-induced curdling allows for slower, more controlled proteolysis. This enzymatic breakdown of proteins during aging releases amino acids and peptides that act as precursors for complex flavor compounds, contributing to the nuanced, earthy, and nutty notes characteristic of traditional cheeses like Cheddar, Parmesan, and Gruyère.

Consider the dosage: typically, 0.02–0.05% rennet (by weight of milk) is added for firm cheeses, while softer varieties may require less. The precise amount depends on milk type, pH, and desired texture. Overuse can lead to bitter flavors due to excessive protein breakdown, while underuse may result in weak curds and bland taste. Timing matters too—adding rennet at 30–35°C (86–95°F) ensures optimal enzyme activity, fostering a balanced flavor profile. For home cheesemakers, using liquid rennet (20–40 drops per gallon of milk) or diluted rennet tablets offers control over this critical step.

A comparative analysis highlights the difference between rennet-coagulated and non-rennet cheeses. For instance, a traditional Cheddar aged 12 months exhibits a rich, savory umami quality, attributed to rennet’s role in breaking down proteins into free amino acids like glutamic acid. In contrast, an acid-coagulated cheese like ricotta lacks this depth, presenting a clean, milky flavor instead. This distinction underscores rennet’s irreplaceable contribution to flavor complexity in aged, hard cheeses.

Practically, cheesemakers can enhance flavor development by controlling aging conditions post-coagulation. For example, a semi-hard cheese aged at 10–12°C (50–54°F) with 85% humidity for 6–8 months will develop a robust, tangy profile, while a longer aging period (12–18 months) at cooler temperatures (8–10°C) can intensify nutty and caramelized notes. Pairing rennet coagulation with specific bacterial cultures, such as *Propionibacterium freudenreichii* in Swiss cheese, further amplifies flavor diversity through additional metabolic pathways.

In conclusion, animal rennet is not merely a coagulating agent but a flavor architect in traditional cheesemaking. Its enzymatic precision unlocks a spectrum of aromas and tastes unattainable through other methods. By mastering dosage, timing, and aging, cheesemakers can harness rennet’s potential to craft cheeses with distinctive, memorable character. For enthusiasts and professionals alike, understanding this interplay between enzyme and milk is key to elevating the art of cheese.

Cloak of Shadow Cheese Secrets in Nighthild: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Yield Efficiency: Rennet maximizes curd yield, reducing whey waste and improving cheese production efficiency

Animal rennet is a crucial enzyme complex derived from the stomach lining of ruminants, primarily calves, goats, and sheep. Its primary function in cheese making is to coagulate milk, transforming it from a liquid state into a solid curd and liquid whey. Among its many roles, rennet’s impact on yield efficiency stands out as a key benefit for cheese producers. By precisely coagulating milk proteins, rennet maximizes curd formation, ensuring that a higher proportion of milk solids are retained in the cheese rather than lost as whey. This not only increases the overall yield but also minimizes waste, making the cheese-making process more economically and environmentally sustainable.

To understand rennet’s role in yield efficiency, consider its mechanism of action. The enzyme chymosin in rennet selectively cleaves the milk protein κ-casein, causing the milk to coagulate into a firm, elastic curd. This process is highly efficient, typically requiring a dosage of 0.02–0.05% rennet solution per volume of milk, depending on factors like milk type and temperature. Compared to alternative coagulants like microbial transglutaminase or plant-based enzymes, rennet produces a stronger curd with less syneresis (moisture loss), resulting in a higher yield of cheese per liter of milk. For example, using animal rennet can increase curd yield by up to 10–15% compared to less precise coagulants, directly translating to greater profitability for producers.

Practical application of rennet for optimal yield efficiency requires careful attention to timing and conditions. The milk should be warmed to 30–35°C (86–95°F) before adding the diluted rennet solution, as this temperature range activates the enzyme without denaturing it. Stir the milk gently for 1–2 minutes to ensure even distribution, then allow it to set undisturbed for 30–60 minutes, depending on the desired curd firmness. Overuse of rennet can lead to brittle curds and reduced yield, while underuse may result in weak, rubbery curds that retain excess moisture. Regularly calibrating rennet dosage based on milk quality and seasonal variations ensures consistent results.

From an economic perspective, rennet’s ability to maximize curd yield directly impacts the bottom line of cheese production. Whey, though valuable in its own right, is less profitable than cheese. By reducing whey waste, producers can allocate more resources to higher-value products. For instance, a small-scale dairy processing 1,000 liters of milk daily could save up to 150 liters of milk solids by using rennet, equivalent to producing an additional 15–20 kg of cheese. Over time, this efficiency gain can offset the cost of rennet, making it a cost-effective investment for both artisanal and industrial cheese makers.

In conclusion, rennet’s role in yield efficiency is a testament to its precision and effectiveness in cheese making. By optimizing curd formation and minimizing whey loss, it not only enhances productivity but also aligns with sustainable practices by reducing waste. For producers seeking to maximize output while maintaining quality, mastering the use of animal rennet is an essential skill. Whether crafting a small batch of artisanal cheese or managing large-scale production, the strategic application of rennet ensures every drop of milk is transformed into its highest-value form.

Effortless Cheese Grating: Using a Mini Food Processor for Perfect Results

You may want to see also

Traditional vs. Alternatives: Animal rennet is preferred for authenticity, though microbial/plant alternatives exist

Animal rennet, derived from the stomach lining of ruminants like calves, lambs, and goats, has been the gold standard in cheese making for centuries. Its primary function is to coagulate milk by breaking down its proteins, specifically kappa-casein, into para-kappa-casein and glycomacropeptide. This process transforms liquid milk into a solid curd and liquid whey, a critical step in cheese production. The enzyme chymosin, found in animal rennet, is highly efficient and produces a clean break, resulting in a firm, smooth curd ideal for traditional cheeses like Parmesan, Cheddar, and Gruyère. For purists, animal rennet is non-negotiable; it imparts a subtle flavor profile and texture that alternatives struggle to replicate, making it the cornerstone of artisanal and heritage cheese making.

However, the rise of vegetarianism, ethical concerns, and religious dietary restrictions has spurred the development of microbial and plant-based alternatives. Microbial rennet, produced through fermentation by fungi or bacteria, contains chymosin identical to that in animal rennet. It offers comparable coagulation properties and is widely used in mass-produced cheeses. Plant-based coagulants, such as those derived from thistle, fig, or safflower, are another option, though they often yield softer curds and can impart distinct flavors, making them better suited for specific cheese varieties like fresh cheeses or aged pecorinos. While these alternatives address ethical and dietary needs, they rarely satisfy traditionalists who prioritize authenticity and historical methods.

The choice between animal rennet and its alternatives often boils down to context and purpose. For small-scale producers aiming to recreate centuries-old recipes, animal rennet remains the preferred choice, despite its higher cost and sourcing challenges. Its precision in curd formation and flavor contribution are unmatched, particularly in hard and semi-hard cheeses where texture is paramount. Conversely, microbial rennet is a practical solution for large-scale production, offering consistency and scalability without compromising quality in many cases. Plant-based coagulants, while niche, cater to vegan markets and experimental cheese makers willing to embrace unique flavor profiles.

Practical considerations also play a role in this decision. Animal rennet typically requires a dosage of 0.02–0.05% of milk weight, while microbial rennet may need slightly higher amounts due to varying potency. Plant coagulants are less predictable, often requiring trial and error to achieve the desired curd firmness. For home cheese makers, microbial rennet is a convenient, shelf-stable option, whereas animal rennet often comes in liquid form with a shorter shelf life. Ultimately, the choice hinges on balancing tradition, ethics, and functionality, with each option offering distinct advantages and trade-offs in the pursuit of the perfect cheese.

Is Your Cheese Snack Zabiha? A Quick Guide to Check

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Animal rennet is a natural enzyme complex derived from the stomach lining of ruminant animals like calves, lambs, or goats. It contains chymosin and pepsin, which coagulate milk by breaking down k-casein proteins, causing milk to curdle and form cheese curds.

Animal rennet is preferred for its efficiency in producing a clean break between curds and whey, resulting in a firmer texture and better yield. It also contributes to the characteristic flavor and structure of traditional cheeses.

Yes, alternatives include microbial (bacterial or fungal) rennet, plant-based coagulants (e.g., fig tree bark or thistle), and genetically engineered rennet. These are often used in vegetarian or vegan cheese production.

Yes, animal rennet typically produces cheeses with a smoother texture and more pronounced flavor compared to other coagulants. However, the overall impact also depends on other factors like milk type, aging, and production methods.

Animal rennet is safe for consumption but is not suitable for vegetarians, vegans, or those with religious dietary restrictions (e.g., kosher or halal). Always check labels for rennet source if dietary concerns apply.