Head cheese, a traditional delicacy made from various parts of a pig's head, often includes a jelly-like substance that can be both intriguing and puzzling to those unfamiliar with it. This jelly is primarily composed of natural gelatin, which forms as the collagen-rich parts of the head, such as skin, tendons, and cartilage, are slowly cooked in a broth. During the cooking process, the collagen breaks down into gelatin, which then solidifies as the mixture cools, creating the characteristic jelly texture. This jelly not only binds the meat and other ingredients together but also adds a unique, savory flavor and a smooth, melt-in-your-mouth consistency to the dish. Understanding the origins and purpose of this jelly can help appreciate head cheese as a carefully crafted culinary tradition rather than just a curious oddity.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Composition | Primarily gelatin, derived from collagen in animal bones, skin, and connective tissues |

| Source | Formed during the cooking process of head cheese, as collagen breaks down into gelatin |

| Texture | Jelly-like, firm yet slightly wobbly when set |

| Appearance | Translucent, often with a pale amber or colorless hue |

| Flavor | Mild, slightly savory, taking on the flavors of the broth and ingredients used in head cheese |

| Function | Acts as a natural binder, holding the meat and other ingredients together in head cheese |

| Nutritional Value | High in protein (from collagen), low in fat, and contains amino acids like glycine and proline |

| Culinary Use | Essential component of traditional head cheese, providing structure and texture |

| Storage | Solidifies when chilled, melts when heated, typical of gelatin-based substances |

| Cultural Variations | Present in various versions of head cheese across different cuisines (e.g., European, American) |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Ingredients in Head Cheese: Explains the components, including gelatin, meat, and spices, that create the jelly texture

- Gelatin Formation Process: Describes how collagen from bones and skin melts into jelly during cooking

- Traditional Preparation Methods: Highlights slow-cooking techniques used to extract natural gelatin for the jelly

- Texture and Appearance: Discusses the translucent, firm jelly that binds the meat pieces together

- Cultural Variations: Explores how different regions add unique ingredients or methods to the jelly mixture

Ingredients in Head Cheese: Explains the components, including gelatin, meat, and spices, that create the jelly texture

The jelly-like substance in head cheese, often a subject of curiosity, is primarily composed of gelatin, a protein derived from collagen found in animal bones, skin, and connective tissues. This natural thickening agent forms when the collagen in meat scraps, particularly from the head of a pig, is slowly cooked in a broth. The process releases gelatin, which solidifies as the mixture cools, creating the distinctive jelly texture. This method not only preserves the meat but also transforms it into a cohesive, sliceable terrine.

To achieve the perfect jelly consistency, the ratio of meat to liquid is crucial. Traditionally, head cheese includes a mix of lean meat, skin, and cartilage from the pig’s head, simmered for hours in a seasoned broth. The slow cooking breaks down collagen-rich tissues, releasing gelatin into the liquid. For every pound of meat, approximately 2–3 quarts of water are used, ensuring enough gelatin is extracted to set the mixture. Adding a splash of vinegar during cooking can enhance gelatin extraction by breaking down collagen more effectively.

Spices and seasonings play a dual role in head cheese: they flavor the dish and complement the jelly texture. Common additions include bay leaves, black peppercorns, cloves, and allspice, which infuse the broth during cooking. These spices not only add depth but also mask any strong flavors from the meat. For a modern twist, some recipes incorporate herbs like thyme or rosemary, or even a hint of garlic, to elevate the taste without overpowering the natural meat flavor.

While gelatin is the star in creating the jelly texture, the choice of meat and its preparation are equally important. Using a mix of fatty and lean cuts ensures a balanced texture—too much fat can prevent proper setting, while too little can make the head cheese dry. After cooking, the meat is shredded or finely chopped and combined with the strained, gelatin-rich broth. Pouring this mixture into a mold and refrigerating it for at least 6 hours allows the gelatin to set, resulting in a firm yet tender terrine.

For those experimenting with head cheese, a practical tip is to test the gelatin content before refrigeration. Place a small amount of the warm broth in the fridge for 15 minutes; if it sets firmly, the mixture has enough gelatin. If not, simmering the broth further or adding unflavored gelatin (1 teaspoon per cup of liquid) can ensure the desired texture. This blend of traditional techniques and modern adjustments makes head cheese a fascinating culinary creation, where the jelly stuff is both functional and flavorful.

Taco Bell Nachos and Cheese: Calculating Points Plus for Your Snack

You may want to see also

Gelatin Formation Process: Describes how collagen from bones and skin melts into jelly during cooking

The jelly-like substance in head cheese is a result of the transformation of collagen, a protein found abundantly in animal bones, skin, and connective tissues. This process, known as gelatin formation, is a fascinating culinary science that turns tough, fibrous materials into a smooth, wobbly gel. When preparing head cheese, the key lies in slow cooking, which allows the collagen to break down and release its gelling properties.

The Science Behind Gelatinization: Collagen is a structural protein composed of amino acids, primarily glycine, proline, and hydroxyproline. During prolonged cooking, typically at temperatures above 140°F (60°C), the collagen fibers unravel and dissolve into the cooking liquid. This process, called hydrolysis, breaks the triple helix structure of collagen, releasing individual collagen peptides. As the liquid cools, these peptides realign and form a three-dimensional network, trapping water molecules and creating the characteristic gel texture.

Cooking Techniques for Optimal Gelatin Formation: To achieve the desired jelly consistency in head cheese, follow these steps:

- Simmer, Don't Boil: Maintain a gentle simmer when cooking the animal parts. High temperatures can cause the collagen to toughen instead of breaking down. Aim for a temperature range of 160-180°F (70-80°C) for several hours.

- Time is Key: The longer you cook, the more collagen will dissolve. For a substantial gel, cook for a minimum of 4-6 hours, or until the bones and skin are soft and easily pierced.

- Acidify for Efficiency: Adding acidic ingredients like vinegar or lemon juice can accelerate collagen breakdown. A pH level of around 4.5-5.0 is ideal for maximizing gelatin extraction.

Troubleshooting Common Issues: If your head cheese doesn't set properly, consider these factors:

- Insufficient Collagen: Ensure you're using enough bones and skin in your recipe. A higher collagen content increases the gelling potential.

- Overcooking: While rare, excessive cooking can degrade the collagen, reducing its gelling ability. Monitor the cooking time and temperature carefully.

- Cooling Process: Gelatin formation occurs during cooling. Allow the mixture to cool slowly at room temperature before refrigerating for best results.

In the context of head cheese, understanding the gelatin formation process is crucial for achieving the desired texture. By mastering the art of collagen extraction, cooks can transform humble ingredients into a delicacy with a unique, jellied consistency. This process not only adds a distinctive mouthfeel but also contributes to the dish's visual appeal, making it a true culinary masterpiece.

Top Dairy State: Leading Milk and Cheese Production in the U.S

You may want to see also

Traditional Preparation Methods: Highlights slow-cooking techniques used to extract natural gelatin for the jelly

The jelly in head cheese isn't added—it's earned. Slow-cooking animal parts rich in collagen, like pig's feet, ears, and skin, breaks down connective tissues, releasing natural gelatin into the cooking liquid. This gelatin, a protein derived from collagen, solidifies as the mixture cools, creating the characteristic jelly.

Traditional methods prioritize low and slow heat, often simmering the ingredients for 6 to 8 hours, or even overnight. This gentle approach ensures complete collagen extraction without toughening the meat. The resulting broth, rich in gelatin, is then combined with shredded meat and vegetables, chilled, and set into the familiar molded form.

This technique isn't just about texture; it's about maximizing flavor and utilizing every part of the animal. The slow cook time allows the bones and cartilage to release their essence, creating a deeply savory jelly that complements the meat. Think of it as a culinary alchemy, transforming humble ingredients into a delicacy through patience and heat.

Unlike modern shortcuts using store-bought gelatin, traditional head cheese relies on the natural gelatin present in the animal itself. This not only results in a more authentic flavor but also aligns with the historical practice of using every part of the animal, minimizing waste.

For those venturing into head cheese making, remember: patience is key. Rushing the process with higher heat will yield a less flavorful and less gelatinous result. Embrace the slow simmer, allowing the ingredients to surrender their essence to the pot. The reward is a jelly that's not just a textural element, but a testament to the transformative power of traditional cooking techniques.

Easy Shredded Cheese to Creamy Dip Transformation: Quick Recipe Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Texture and Appearance: Discusses the translucent, firm jelly that binds the meat pieces together

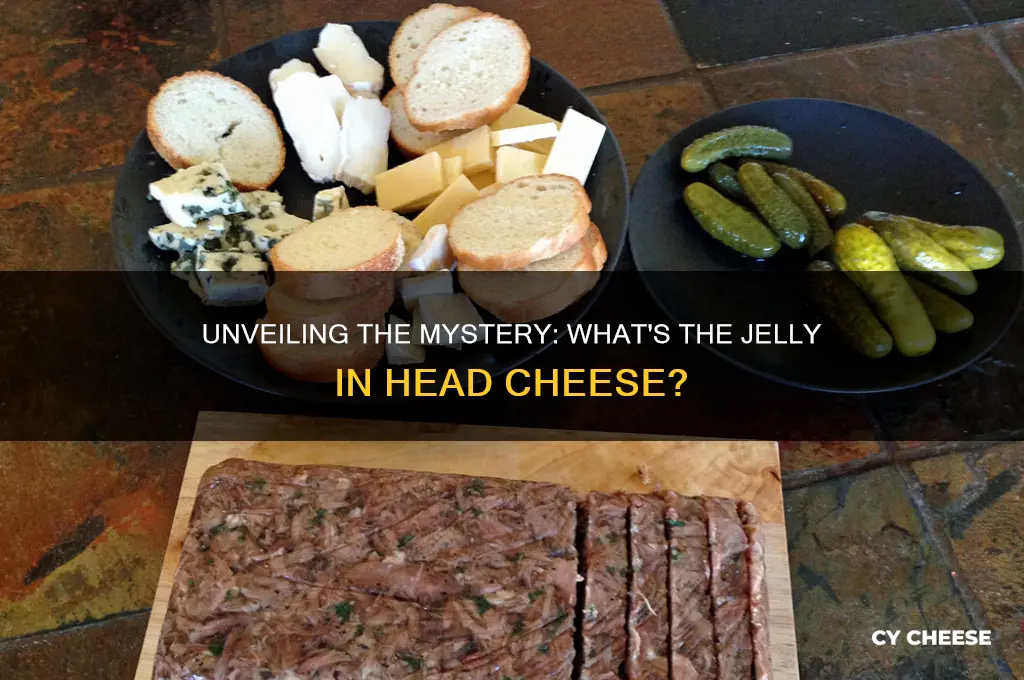

The jelly in head cheese is a natural byproduct of the cooking process, formed as collagen-rich cuts of meat, like pig’s feet or trotters, break down in simmering liquid. This gelatinous substance is not added artificially but emerges as the connective tissues dissolve, creating a translucent, firm matrix that binds the meat pieces together. Its clarity and slight shimmer are indicators of proper preparation, where the broth has been strained and cooled slowly to allow the jelly to set uniformly.

To achieve the ideal texture, start by simmering collagen-rich ingredients (e.g., trotters, ears, or tails) for 3–4 hours in a broth seasoned with vinegar, salt, and aromatics. The low-and-slow cooking method ensures the collagen fully converts to gelatin. Once cooked, strain the broth through a fine-mesh sieve to remove impurities, then pour it over the meat pieces in a mold. Refrigerate for at least 12 hours to allow the jelly to firm up. For a clearer jelly, avoid stirring the broth after straining and skim off any fat that rises to the surface before cooling.

Comparatively, the jelly in head cheese differs from commercial gelatin desserts in both origin and purpose. While desserts rely on powdered gelatin derived from animal bones, head cheese jelly is a direct result of cooking specific cuts of meat. Its texture is firmer yet yielding, designed to hold structural integrity rather than melt on the palate. This distinction highlights the craft of traditional charcuterie, where every element serves a functional and aesthetic role.

Practically, the jelly’s appearance and texture can be enhanced by controlling the cooling process. For a smoother, more even set, use shallow containers instead of deep molds. If the jelly is too soft, increase the collagen content by adding more trotters or using a longer simmer time. Conversely, if it’s too rubbery, reduce the cooking time or dilute the broth slightly. Serving head cheese at room temperature softens the jelly slightly, improving its mouthfeel, while chilled slices offer a satisfying snap.

Ultimately, the jelly in head cheese is both a structural necessity and a testament to culinary technique. Its translucent, firm nature not only binds the dish together but also showcases the transformation of humble ingredients into something cohesive and elegant. By understanding its formation and manipulating its properties, even novice cooks can master this traditional delicacy, turning what might seem off-putting to some into a celebrated centerpiece.

Tiny White Spots on Cheese: Causes and Safety Explained

You may want to see also

Cultural Variations: Explores how different regions add unique ingredients or methods to the jelly mixture

The jelly in head cheese, often a gelatinous concoction derived from animal collagen, serves as both binder and flavor enhancer. Across cultures, this unassuming element transforms through regional ingenuity, reflecting local ingredients and culinary philosophies. In Germany, for instance, *Sülze* incorporates vinegar and mustard seeds, lending a sharp tang that cuts through the richness of pork or beef. This method not only preserves but elevates, showcasing how acidity can balance the dish’s inherent heaviness.

Contrast this with Italy’s *Coppa di Testa*, where tomatoes, white wine, and herbs like rosemary infuse the jelly with Mediterranean vibrancy. Here, the focus shifts from preservation to integration, as the jelly absorbs flavors akin to a broth, creating a cohesive, aromatic experience. Such variations highlight how regional climate and agricultural abundance dictate not just ingredients but the very character of the dish.

In Asia, particularly China, *Eluo* (a variation of head cheese) often includes star anise, ginger, and soy sauce, resulting in a jelly that’s both savory and subtly sweet. This approach underscores the importance of umami and warmth in balancing the dish’s texture. Notably, the jelly here isn’t merely structural—it’s a medium for delivering complex, layered flavors, often achieved by simmering bones and spices for upwards of 8 hours to extract maximum depth.

For those experimenting at home, consider these cultural cues as blueprints. Start with a base of pork trotters or skin, simmered until collagen dissolves into a rich liquid. Then, tailor the jelly to your palate: add 2 tablespoons of apple cider vinegar and a teaspoon of black peppercorns for a Germanic twist, or 1 cup of tomato puree and a sprig of thyme for an Italian flair. The key lies in understanding that the jelly isn’t just a byproduct—it’s a canvas for cultural expression.

Ultimately, these regional adaptations prove that head cheese’s jelly is far from uniform. It’s a testament to how necessity—preserving every part of an animal—evolves into artistry, shaped by geography, history, and creativity. Whether sharp, herbal, or spiced, each variation invites a deeper appreciation for this humble, often misunderstood dish.

Mastering Jersey Mike's Online Cheese Orders: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The jelly in head cheese is typically aspic, a savory gelatin made from the natural collagen and gelatin found in animal bones, skin, and connective tissues. It solidifies as the mixture cools, creating a jelly-like texture.

Yes, the jelly in head cheese is safe to eat. It is made from natural ingredients and is a traditional part of the dish, providing both texture and flavor.

No, the jelly in head cheese is derived from animal collagen and gelatin, so it cannot be made without animal products. However, vegetarian or vegan alternatives to aspic exist, though they would not be used in traditional head cheese.