The disaccharide found in cheese is lactose, commonly known as milk sugar. Lactose is composed of two simple sugars, glucose and galactose, linked together. It is a natural component of milk and dairy products, including cheese, where it contributes to the characteristic sweetness and texture. During the cheese-making process, lactose is partially broken down by bacteria, but some remains, particularly in softer, fresher cheeses. Understanding lactose is essential, as it plays a role in both the sensory qualities of cheese and its digestibility, especially for individuals with lactose intolerance.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Lactose Definition: Lactose is the disaccharide sugar found in milk and dairy products like cheese

- Lactose Structure: Composed of glucose and galactose molecules bonded together

- Role in Cheese: Lactose serves as food for bacteria during cheese fermentation

- Lactose Intolerance: Some people lack enzymes to digest lactose, causing discomfort

- Lactose in Aging: Lactose breaks down during cheese aging, affecting flavor and texture

Lactose Definition: Lactose is the disaccharide sugar found in milk and dairy products like cheese

Lactose, a disaccharide sugar composed of glucose and galactose, is the primary carbohydrate found in milk and dairy products like cheese. Its presence is essential for the nutritional value of these foods, providing energy and aiding in the absorption of certain minerals such as calcium. However, lactose is also the culprit behind lactose intolerance, a condition where the body lacks sufficient lactase, the enzyme needed to break down lactose into its constituent sugars. This can lead to digestive discomfort, including bloating, gas, and diarrhea, for those affected. Understanding lactose’s role in cheese and dairy is crucial for both dietary choices and managing intolerance symptoms.

From a nutritional standpoint, lactose serves as more than just a sugar. In cheese, its concentration varies depending on the type and production method. For instance, hard cheeses like cheddar have lower lactose levels due to the fermentation process, which consumes much of the lactose. In contrast, soft cheeses like ricotta retain higher amounts. This variation is important for individuals with lactose intolerance, as it allows them to make informed choices. For example, a person with mild intolerance might tolerate a small serving of hard cheese but should avoid cream cheese or fresh mozzarella. Monitoring portion sizes and pairing lactose-containing foods with lactase supplements can also help mitigate symptoms.

The role of lactose in cheese extends beyond nutrition to influence texture and flavor. During cheese production, lactose is partially broken down by bacteria, contributing to the development of acidity and the characteristic tanginess of fermented dairy products. This process not only reduces lactose content but also creates byproducts that enhance flavor complexity. For instance, lactic acid, a byproduct of lactose fermentation, is responsible for the sharp taste in aged cheeses. Thus, lactose is not merely a sugar but a key player in the sensory qualities of cheese, making it a fascinating subject for both food scientists and culinary enthusiasts.

For those managing lactose intolerance, practical strategies can make a significant difference. Gradual exposure to small amounts of lactose can help some individuals build tolerance over time. Additionally, combining lactose-containing foods with other nutrients can slow digestion and reduce symptoms. For example, pairing cheese with fiber-rich foods like whole-grain crackers or vegetables can lessen the impact on the digestive system. Lactase enzyme supplements, available over the counter, can also be taken before consuming dairy to aid in lactose digestion. These approaches allow individuals to enjoy cheese and other dairy products without discomfort, highlighting the importance of understanding lactose’s role in both health and culinary experiences.

Raw Cheese vs. Regular Cheese: Understanding the Key Differences

You may want to see also

Lactose Structure: Composed of glucose and galactose molecules bonded together

Lactose, the primary disaccharide found in cheese, is a fascinating molecule with a unique structure. It is composed of two simple sugars—glucose and galactose—bonded together by a glycosidic linkage. This specific arrangement not only defines lactose’s chemical identity but also influences its role in digestion and its presence in dairy products like cheese. Understanding this structure is key to grasping why lactose behaves the way it does in both biological and culinary contexts.

Analytically, the bond between glucose and galactose in lactose is a β-1,4-glycosidic linkage, which distinguishes it from other disaccharides like sucrose or maltose. This linkage requires the enzyme lactase for digestion, as it is not naturally broken down by stomach acids or other enzymes. In cheese, lactose is present in varying amounts depending on the aging process; fresher cheeses retain more lactose, while aged varieties have less due to bacterial breakdown. For individuals with lactose intolerance, this structural detail explains why they may tolerate aged cheeses better than fresh ones.

From an instructive perspective, recognizing lactose’s structure can guide dietary choices. For example, if you’re lactose intolerant, opting for harder, aged cheeses like cheddar or Parmesan can reduce discomfort because their lower lactose content stems from the breakdown of this disaccharide during aging. Conversely, soft cheeses like mozzarella or cream cheese retain more lactose and may require portion control or pairing with lactase supplements for comfortable consumption. Practical tip: Start with small servings of aged cheeses to test tolerance and gradually increase intake.

Persuasively, the structure of lactose highlights its importance in cheese production. During cheesemaking, lactose serves as a food source for lactic acid bacteria, which ferment it into lactic acid. This process not only preserves the cheese but also contributes to its flavor and texture. Without lactose’s specific glucose-galactose bond, this fermentation wouldn’t occur, and cheese as we know it wouldn’t exist. This underscores why lactose is more than just a sugar—it’s a cornerstone of dairy chemistry.

Comparatively, lactose’s structure sets it apart from other disaccharides in terms of its metabolic impact. Unlike sucrose, which is quickly absorbed, lactose’s unique bond requires enzymatic action, making its digestion slower and more dependent on individual lactase production. This distinction is why lactose intolerance is so prevalent, especially in populations with historically low dairy consumption. In contrast, the universal digestibility of glucose and galactose as individual sugars highlights the critical role of their bonding in lactose’s behavior.

Descriptively, lactose’s structure can be visualized as a molecular partnership where glucose and galactose are linked in a precise, stable configuration. This bond is both its strength and its weakness—stable enough to survive mild processing but fragile enough to be broken down by specific enzymes or bacteria. In cheese, this duality is evident: lactose’s structure allows it to contribute to the cheese’s initial sweetness and texture, yet its breakdown during aging transforms the final product. This interplay of stability and vulnerability is what makes lactose such a dynamic component of dairy.

Gloucestershire Cheese Roll: Fatalities and Risks of the Annual Chase

You may want to see also

Role in Cheese: Lactose serves as food for bacteria during cheese fermentation

Lactose, the disaccharide found in cheese, plays a pivotal role in the fermentation process that defines cheese production. As the primary carbohydrate in milk, lactose serves as the essential food source for lactic acid bacteria (LAB), which are integral to cheese making. During fermentation, these bacteria metabolize lactose, breaking it down into lactic acid and other byproducts. This process not only lowers the pH of the milk, facilitating curdling, but also contributes to the development of flavor, texture, and preservation of the final cheese product. Without lactose, the bacterial activity necessary for cheese fermentation would be severely compromised, underscoring its critical role in the transformation of milk into cheese.

From an analytical perspective, the breakdown of lactose by LAB is a highly regulated and precise process. The rate of lactose fermentation depends on factors such as temperature, bacterial strain, and milk composition. For instance, mesophilic bacteria, which thrive at temperatures between 20°C and 40°C, ferment lactose more slowly, resulting in milder flavors, as seen in cheeses like Cheddar. In contrast, thermophilic bacteria, active at 40°C to 55°C, ferment lactose rapidly, producing sharper, more complex flavors typical of cheeses like Parmesan. Understanding these dynamics allows cheese makers to manipulate fermentation conditions to achieve desired sensory profiles, highlighting the strategic importance of lactose in cheese production.

For those interested in home cheese making, recognizing the role of lactose is crucial for troubleshooting common issues. If lactose fermentation is incomplete, the cheese may retain a sweet, milky flavor, indicating insufficient bacterial activity. To ensure optimal fermentation, maintain a consistent temperature within the recommended range for the specific bacterial culture used. Additionally, monitor the pH of the curd; a drop to around 5.0–5.4 typically signifies adequate lactose breakdown. For harder cheeses, reducing the lactose content in the milk before fermentation can be achieved by allowing the milk to acidify slightly, a technique often used in traditional recipes.

Comparatively, lactose’s role in cheese fermentation contrasts with its function in other dairy products like yogurt, where it is also fermented but results in a different end product. In cheese, the partial or complete breakdown of lactose contributes to the solidification of curds and the expulsion of whey, whereas in yogurt, lactose fermentation primarily thickens the milk. This distinction highlights how the same disaccharide can drive vastly different outcomes based on the microbial processes involved. Such comparisons underscore the versatility of lactose in dairy science and its tailored role in cheese fermentation.

Finally, the practical implications of lactose in cheese extend to dietary considerations. While lactose is fully metabolized during fermentation in aged cheeses, trace amounts may remain in fresher varieties, posing concerns for lactose-intolerant individuals. However, harder, longer-aged cheeses like Swiss or Cheddar typically contain negligible lactose, making them suitable for most diets. For cheese makers, this presents an opportunity to cater to diverse consumer needs by controlling fermentation duration and bacterial activity. By mastering the role of lactose in cheese fermentation, producers can create products that are both delicious and inclusive.

Prevent Scorching: Tips for Perfect Milk and Cheese Preparation

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Lactose Intolerance: Some people lack enzymes to digest lactose, causing discomfort

Lactose, a disaccharide found in cheese and other dairy products, is composed of glucose and galactose molecules bonded together. For most people, the enzyme lactase, produced in the small intestine, breaks down lactose into these simpler sugars for absorption. However, individuals with lactose intolerance lack sufficient lactase, leading to undigested lactose fermenting in the gut. This process produces gas, bloating, diarrhea, and abdominal pain—symptoms that can range from mild to severe depending on the degree of lactase deficiency. Understanding this enzymatic shortfall is key to managing discomfort and making informed dietary choices.

Consider the prevalence of lactose intolerance, which affects approximately 65% of the global population, with higher rates in certain ethnic groups such as Asians, Africans, and Native Americans. The condition often develops in adulthood as lactase production naturally declines. For those affected, consuming dairy products like cheese can become a gamble with digestive health. Interestingly, not all cheeses are equally problematic. Hard cheeses like cheddar or Swiss contain lower lactose levels due to the fermentation process, making them more tolerable for some individuals. This highlights the importance of understanding both the biochemistry of lactose and the variability in dairy products.

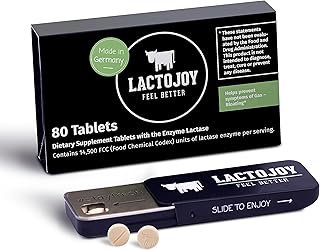

To mitigate discomfort, individuals with lactose intolerance can adopt practical strategies. Over-the-counter lactase enzymes, available in tablet or liquid form, can be taken before consuming dairy to aid digestion. Dosages typically range from 3,000 to 9,000 FCC units, depending on the amount of lactose consumed. Alternatively, lactose-free or reduced-lactose cheeses are widely available, offering a convenient solution without sacrificing flavor. For those who prefer a trial-and-error approach, starting with small portions of low-lactose cheeses and monitoring symptoms can help identify personal tolerance levels. Combining these methods allows individuals to enjoy dairy while minimizing adverse effects.

A comparative analysis reveals that lactose intolerance is not an allergy but rather a digestive limitation. Unlike dairy allergies, which involve the immune system and can be life-threatening, lactose intolerance is generally manageable and non-dangerous. However, the discomfort it causes can significantly impact quality of life, particularly for those who rely on dairy as a calcium source. This distinction underscores the need for tailored dietary adjustments rather than complete avoidance. For instance, pairing lactose-containing foods with non-dairy calcium sources like leafy greens or fortified beverages ensures nutritional balance without triggering symptoms.

Finally, lactose intolerance serves as a reminder of the intricate relationship between diet and digestive health. While it may seem restrictive, it also encourages exploration of diverse, dairy-free alternatives like almond, soy, or oat-based cheeses. These options not only cater to lactose-intolerant individuals but also align with broader dietary trends toward plant-based eating. By embracing both scientific understanding and culinary innovation, those affected can navigate lactose intolerance with confidence, turning a potential limitation into an opportunity for dietary enrichment.

Discover the Best Spots for Cheese Curds in Los Angeles

You may want to see also

Lactose in Aging: Lactose breaks down during cheese aging, affecting flavor and texture

Lactose, the disaccharide found in cheese, undergoes a transformative journey during the aging process, significantly influencing both flavor and texture. As cheese matures, lactose breaks down into simpler sugars—glucose and galactose—through the action of enzymes like lactase and bacterial metabolism. This breakdown is a cornerstone of cheese aging, contributing to the development of complex flavors and the desired texture profiles that distinguish aged cheeses from their fresher counterparts.

Analytically, the rate of lactose breakdown depends on factors such as cheese type, bacterial culture, and aging conditions. For instance, hard cheeses like Parmesan age for months or even years, allowing for a slow, gradual breakdown of lactose. This prolonged process results in a drier texture and a nutty, umami-rich flavor. In contrast, semi-soft cheeses like Cheddar age more rapidly, leading to a creamier texture and sharper taste. Understanding these dynamics allows cheesemakers to manipulate aging conditions—such as temperature and humidity—to achieve specific sensory outcomes.

From a practical standpoint, lactose breakdown during aging is particularly relevant for individuals with lactose intolerance. While fresh cheeses like mozzarella retain much of their lactose, aged cheeses contain significantly less, making them more tolerable. For example, a 30-gram serving of aged Cheddar (aged 6+ months) contains less than 0.5 grams of lactose, compared to 3 grams in the same amount of fresh cheese. This makes aged cheeses a viable option for those who need to limit lactose intake, though individual tolerance varies.

Comparatively, the role of lactose breakdown in cheese aging can be likened to the fermentation process in winemaking. Just as yeast converts sugar to alcohol, shaping the wine’s flavor and body, lactose breakdown in cheese drives the development of its unique characteristics. However, unlike wine, cheese aging is a more delicate balance of enzymatic activity and microbial interaction, requiring precise control to avoid off-flavors or textural defects. This highlights the artistry and science behind cheesemaking, where small adjustments yield significant results.

In conclusion, lactose breakdown during cheese aging is a critical process that shapes the sensory experience of cheese. By understanding its mechanisms and implications, both cheesemakers and consumers can appreciate the transformation from milk to masterpiece. Whether crafting a batch of aged Gouda or selecting a cheese board, recognizing the role of lactose in aging enhances the enjoyment and practicality of this timeless food.

Mastering the Chipotle App: Ordering the Perfect Bean and Cheese Burrito

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The disaccharide found in cheese is lactose.

Lactose is present in cheese because it is derived from milk, and milk naturally contains lactose as a primary carbohydrate.

Not all cheese contains lactose; harder, aged cheeses like cheddar or Parmesan typically have lower lactose levels due to the fermentation process, while softer cheeses may retain more lactose.