The orange stuff on Muenster cheese is actually a protective coating known as annatto, a natural dye derived from the seeds of the achiote tree. This vibrant orange-red substance is commonly used in the cheese-making process to give Muenster its distinctive appearance, though it does not affect the flavor. Annatto has been used for centuries in various food products for its coloring properties and is considered safe for consumption. While some Muenster cheeses are left uncolored, the orange variety remains a popular choice, often associated with the traditional look of this semi-soft, mild cheese.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name | Annatto |

| Source | Derived from the seeds of the achiote tree (Bixa orellana) |

| Purpose | Natural coloring agent |

| Appearance | Orange-yellow paste or powder |

| Flavor Impact | Neutral (does not affect cheese flavor) |

| Common Use | Added to Muenster, Cheddar, and other cheeses for color |

| Safety | Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) by the FDA |

| Historical Use | Used for centuries in food and textiles |

| Alternative Names | Achiote, Lipstick Tree Extract |

| Chemical Composition | Contains bixin and norbixin (carotenoid pigments) |

| Allergenicity | Rarely causes allergic reactions |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Natural Rind Formation: Orange coating is a natural rind, formed during aging, safe to eat

- Bacterial Growth: Annatto-loving bacteria create the orange hue during cheese maturation

- Annatto Color: Derived from achiote seeds, annatto adds the distinctive orange color

- Flavor Impact: Rind contributes nutty, earthy flavors to the cheese’s overall taste

- Edibility: Orange rind is edible, though some prefer removing it for texture

Natural Rind Formation: Orange coating is a natural rind, formed during aging, safe to eat

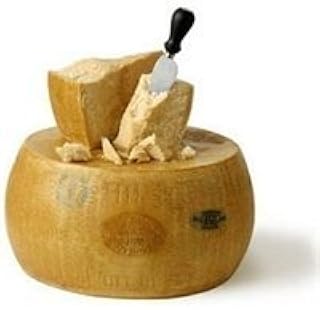

The orange coating on Muenster cheese is not a cause for alarm—it’s a natural rind that develops during the aging process. This rind is a hallmark of traditional Muenster production, particularly in European varieties, where the cheese is exposed to specific molds and bacteria that contribute to its distinctive appearance. Unlike processed coatings, this rind is entirely safe to eat and adds a nuanced flavor profile to the cheese. For those curious about its safety, rest assured: the microorganisms involved in rind formation are non-pathogenic and part of the cheese’s intended character.

To understand how this rind forms, consider the aging environment. Muenster cheese is typically aged in cool, humid conditions, where naturally occurring molds and bacteria thrive. These microorganisms, often from the genus *Brevibacterium*, produce pigments that give the rind its orange hue. The process is carefully monitored to ensure the rind develops evenly and safely. Artisan cheesemakers often wash the cheese with brine or other solutions during aging to encourage this growth, creating a rind that is both protective and flavorful.

If you’re hesitant to eat the rind, consider this: it’s a concentrated source of the cheese’s complex flavors. The rind’s earthy, nutty, and slightly tangy notes complement the creamy interior, enhancing the overall tasting experience. To fully appreciate Muenster, pair it with a crusty baguette or a full-bodied wine, allowing the rind’s texture and taste to shine. For cooking, leave the rind intact when melting the cheese—it adds depth to dishes like grilled cheese sandwiches or cheese boards.

Practical tip: When storing Muenster with a natural rind, wrap it in wax or parchment paper rather than plastic. This allows the cheese to breathe while preventing excessive moisture loss. If the rind becomes too hard or dry, trim a small portion before serving, but avoid removing it entirely unless you prefer a milder flavor. For those with sensitive palates, start by tasting a small piece of the rind to acclimate to its robust flavor.

In comparison to cheeses with artificial coatings or wax rinds, Muenster’s natural rind is a testament to traditional craftsmanship. It’s a feature, not a flaw, and its presence indicates a cheese that has been aged with care. While some may prefer rindless varieties for convenience, the natural rind offers a deeper connection to the cheese’s origins and the artistry of its creation. Embrace it as part of the experience—it’s safe, flavorful, and a key element of what makes Muenster unique.

Heating Cheese: How Temperature Alters Its Chemical Composition and Flavor

You may want to see also

Bacterial Growth: Annatto-loving bacteria create the orange hue during cheese maturation

The orange hue on Muenster cheese isn’t a mistake—it’s the handiwork of annatto-loving bacteria thriving during maturation. These microorganisms, naturally present in the cheese environment, metabolize annatto, a plant-derived coloring agent often added to cheese curds. As the cheese ages, these bacteria break down annatto’s compounds, releasing pigments that deepen the orange shade. This process isn’t just aesthetic; it’s a sign of controlled bacterial activity contributing to flavor development. Without these bacteria, the annatto would remain inert, leaving the cheese pale and less vibrant.

To harness this bacterial magic, cheesemakers follow precise steps. First, annatto is mixed into the milk or curds at a dosage of 0.1–0.5% by weight, depending on the desired intensity. During the aging process, typically 4–8 weeks, the cheese is stored in a controlled environment (50–55°F, 85% humidity) to encourage bacterial growth. Regular flipping and monitoring ensure even pigment distribution. Caution: Overuse of annatto or improper storage can lead to uneven coloring or off-flavors. For home cheesemakers, start with smaller batches and adjust annatto quantities gradually.

Comparatively, cheeses without annatto or these bacteria, like traditional French Muenster, remain pale yellow. The orange variant, popularized in the U.S., showcases how human intervention and microbial activity can transform a product. While some purists argue against annatto, its use highlights the interplay between tradition and innovation in cheesemaking. The bacteria’s role isn’t just to color—it’s a marker of the cheese’s journey from curd to mature wheel.

Practically, understanding this process helps consumers appreciate what they’re eating. The orange hue isn’t artificial dye but a byproduct of natural bacterial metabolism. For those with dietary restrictions, annatto is plant-based and safe for vegetarians. To preserve the color and flavor, store Muenster in the refrigerator, wrapped in wax or parchment paper, and consume within 2–3 weeks of opening. Pair it with fruits or crackers to complement its mild, tangy profile, enhanced by the very bacteria that painted it orange.

Why Cutting the Nose of the Cheese Ruins Its Flavor and Texture

You may want to see also

Annatto Color: Derived from achiote seeds, annatto adds the distinctive orange color

The orange hue on Muenster cheese isn’t mold or a sign of spoilage—it’s annatto, a natural coloring derived from the seeds of the achiote tree. This vibrant pigment has been used for centuries in food and textiles, prized for its ability to impart a warm, orange-yellow tone without altering flavor. While annatto is safe for most people, it’s worth noting that a small percentage of individuals may experience mild allergic reactions, such as skin irritation or digestive discomfort. If you’re sensitive to food additives, consider opting for annatto-free Muenster, which is often available in specialty cheese shops.

To incorporate annatto into your own recipes, start with a minimal dosage—typically 0.1% to 0.5% of the total weight of the product. For example, if you’re making 1 kilogram of cheese, use 1 to 5 grams of annatto extract. Dissolve the annatto in a small amount of warm water or oil before mixing it into your recipe to ensure even distribution. This method works not only for cheese but also for butter, rice, and baked goods. Always source food-grade annatto extract from reputable suppliers to avoid contaminants.

Comparing annatto to synthetic food colorings like beta-carotene or FD&C Yellow 6 highlights its natural appeal. Unlike artificial dyes, annatto is plant-based and free from controversial chemicals, making it a preferred choice for health-conscious consumers. However, it’s less stable than some synthetic options and may fade when exposed to light or heat. To preserve the color in Muenster cheese, store it in a dark, cool place and wrap it tightly in wax or parchment paper.

For families, annatto is a kid-friendly way to make meals visually appealing without resorting to artificial additives. Use it to tint macaroni and cheese, scrambled eggs, or even homemade playdough. When introducing annatto to children, start with small amounts to ensure they don’t react adversely. Pairing annatto-colored dishes with a balanced diet rich in fruits and vegetables can also help children associate vibrant colors with healthy eating habits.

In conclusion, annatto’s role in Muenster cheese is both functional and aesthetic, offering a natural alternative to synthetic dyes. By understanding its origins, proper usage, and benefits, you can confidently enjoy or experiment with this ancient coloring agent. Whether you’re a home cook, a cheese enthusiast, or a parent, annatto provides a simple yet impactful way to elevate your culinary creations.

Perfect Lasagna: Ricotta Cheese and Egg Ratio Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Flavor Impact: Rind contributes nutty, earthy flavors to the cheese’s overall taste

The orange exterior on Muenster cheese, often mistaken for mere coloring, is actually a washed rind that plays a pivotal role in flavor development. This rind is a living ecosystem, hosting bacteria that transform the cheese’s surface through a process called smear-ripening. As the rind matures, it contributes a spectrum of nutty and earthy notes that permeate the interior, enriching the cheese’s overall taste profile. These flavors are not just superficial; they are a direct result of the rind’s microbial activity, which breaks down proteins and fats into complex compounds. Understanding this process reveals why the rind is not just a protective layer but a flavor powerhouse.

To fully appreciate the rind’s impact, consider the aging process. A young Muenster, aged 4–6 weeks, will have a milder rind with subtle earthy undertones, while a cheese aged 8–12 weeks develops a more pronounced nuttiness, akin to roasted almonds or hazelnuts. The longer the cheese ages, the deeper these flavors become, often accompanied by a slightly savory, umami quality. For optimal flavor extraction, allow the cheese to come to room temperature before serving, as this softens the rind and releases its aromatic compounds. Pairing aged Muenster with a crisp apple or a slice of crusty bread can further enhance the nutty and earthy notes, creating a balanced sensory experience.

If you’re hesitant to consume the rind, reconsider its role as a flavor enhancer rather than a barrier. While some prefer to trim it for aesthetic reasons, leaving the rind intact during cooking—such as in grilled cheese or melted over dishes—infuses the entire preparation with its rich, complex flavors. For those concerned about texture, the rind becomes softer and more palatable as the cheese ages, making older Muenster a better candidate for rind-inclusive enjoyment. Experimenting with rind-on versus rind-off tastings can help you discern its direct impact on the cheese’s overall character.

Finally, the rind’s contribution to Muenster’s flavor profile underscores the importance of craftsmanship in cheesemaking. The smear-ripening process, which involves regularly washing the rind with brine or other solutions, is labor-intensive but essential for developing those signature nutty and earthy flavors. When selecting Muenster, look for a rind that is evenly colored and free of excessive moisture, as these are signs of proper care during aging. By valuing the rind’s role, you not only honor the cheesemaker’s artistry but also elevate your own culinary experiences.

Is Domino's Cheese in the USA Made with Animal Rennet?

You may want to see also

Edibility: Orange rind is edible, though some prefer removing it for texture

The orange rind on Muenster cheese is a byproduct of the aging process, specifically the application of annatto, a natural coloring derived from the seeds of the achiote tree. This coating serves both aesthetic and protective purposes, enhancing the cheese’s appearance while shielding it from mold. While entirely edible, the rind’s texture contrasts sharply with the cheese’s creamy interior, leading some to remove it before consumption. This decision often hinges on personal preference and the intended use of the cheese, whether melted in a dish or served as part of a cheese board.

For those considering whether to eat the rind, it’s helpful to understand its composition. The orange layer is typically a blend of annatto and wax or paraffin, both of which are safe for consumption but lack the flavor profile of the cheese itself. To assess edibility, examine the rind’s thickness and flexibility—thinner, softer rinds are more palatable than thicker, rubbery ones. If unsure, a small taste test can provide clarity, though removing it ensures a smoother, more consistent eating experience.

When preparing Muenster for cooking, the rind’s fate depends on the recipe. In dishes like grilled cheese or fondue, where the cheese melts, the rind can be left intact, as it softens and integrates without affecting flavor. However, in cold applications such as sandwiches or salads, removing the rind prevents an unwanted textural contrast. For optimal results, use a sharp knife to carefully trim the rind, ensuring minimal cheese loss while achieving the desired consistency.

Children and individuals with sensory sensitivities may find the rind’s texture off-putting, making removal a practical choice for family meals. Similarly, when serving Muenster as part of a cheese platter, consider slicing the cheese rind-side down or trimming it entirely to enhance visual appeal and ease of eating. For those who enjoy the rind’s subtle earthy notes, pairing it with crackers or bread can balance its texture and make it a more enjoyable component of the dish.

Ultimately, the decision to eat or remove the orange rind on Muenster cheese is a matter of personal taste and context. While entirely safe to consume, its texture and lack of significant flavor contribution often make it a candidate for removal, particularly in dishes where smoothness is key. By understanding its purpose and experimenting with both options, cheese enthusiasts can tailor their Muenster experience to suit their preferences and culinary needs.

Perfectly Baked Brie: Easy Oven Method for Melty Cheese Delight

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The orange stuff on Muenster cheese is typically a natural rind or coating, often made from annatto, a plant-based dye derived from the seeds of the achiote tree. It is used for color and does not affect the flavor.

Yes, the orange coating on Muenster cheese is safe to eat. It is primarily annatto, a natural food coloring, and is commonly consumed without any health concerns.

Muenster cheese is often colored orange using annatto to differentiate it from other cheeses and for aesthetic appeal. Traditionally, Muenster cheese is white, but the orange variety is more common in the United States.

Yes, you can remove the orange coating (rind) from Muenster cheese if you prefer, though it is edible. The rind is primarily for appearance and does not significantly impact the flavor of the cheese.