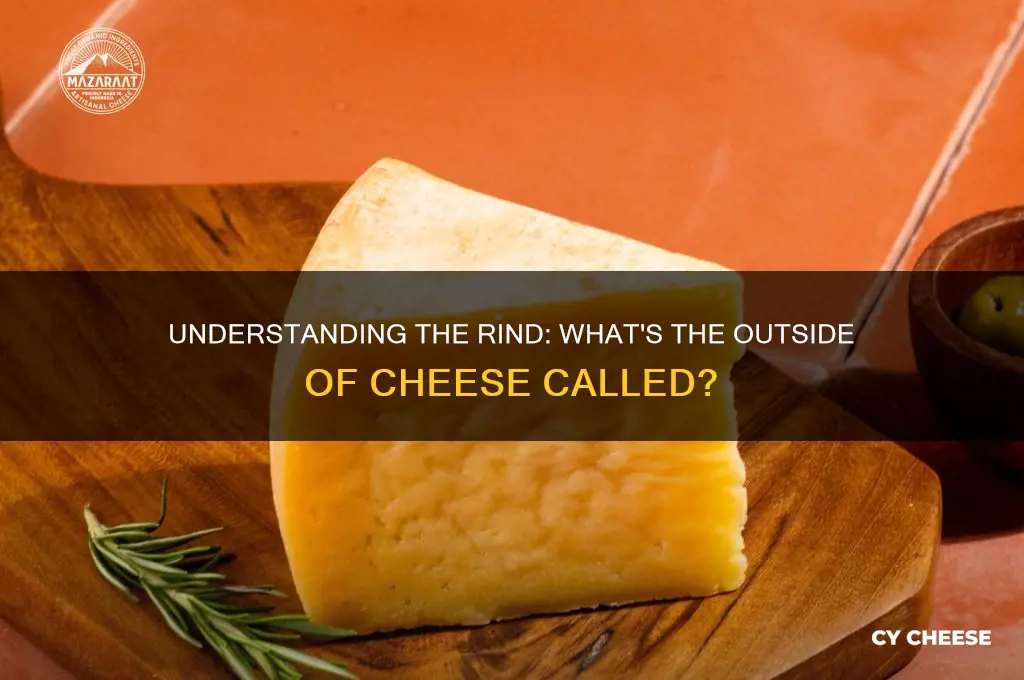

The outer layer of cheese, often referred to as the rind, is a fascinating and essential component that serves multiple purposes. It can be made from various materials, including wax, plastic, or natural mold, and its primary function is to protect the cheese from spoilage and external contaminants. The rind's texture, color, and thickness vary depending on the cheese type and production method, with some rinds being edible and contributing to the overall flavor profile, while others are meant to be removed before consumption. Understanding the role of the cheese rind is crucial for appreciating the complexities of cheese-making and the unique characteristics of different cheese varieties.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Rind Types: Natural, bloomy, waxed, or artificial rinds vary by cheese type and aging process

- Rind Formation: Bacteria, mold, or wax applied during cheese production creates the outer layer

- Edibility of Rind: Some rinds are edible, adding flavor, while others are removed before eating

- Rind Function: Protects cheese from spoilage, influences texture, and contributes to flavor development

- Rindless Cheese: Fresh cheeses like mozzarella or ricotta lack a rind due to minimal aging

Rind Types: Natural, bloomy, waxed, or artificial rinds vary by cheese type and aging process

The outer layer of cheese, known as the rind, is far from a one-size-fits-all feature. It’s a dynamic element shaped by the cheese type, aging process, and desired flavor profile. Rinds fall into distinct categories—natural, bloomy, waxed, and artificial—each serving a unique purpose in protecting, flavoring, and maturing the cheese within. Understanding these types unlocks a deeper appreciation for the craft behind every wheel or wedge.

Natural rinds develop organically during aging, often from bacteria or molds present in the environment. Think of aged cheddar or Parmigiano-Reggiano, where the rind hardens over time, acting as a protective barrier. These rinds are typically inedible but play a crucial role in moisture control and flavor development. For instance, a natural rind on a Gruyère allows the interior to become nutty and complex while preventing excessive drying. If you’re aging cheese at home, ensure proper humidity (around 85-90%) to encourage a healthy natural rind without spoilage.

Bloomy rinds, on the other hand, are soft, velvety, and often edible, thanks to the introduction of *Penicillium camemberti* or *Penicillium candidum*. Camembert and Brie are classic examples, where the rind contributes to the creamy texture and earthy flavor of the cheese. To maintain a bloomy rind, store the cheese in a breathable container at 50-55°F, allowing the mold to thrive without trapping excess moisture. Pairing a bloomy-rind cheese with a crisp white wine enhances its delicate profile.

Waxed rinds serve a purely functional purpose, sealing in moisture and preventing mold growth. Gouda and Edam are often coated in wax, which keeps the interior semi-firm and mild. While the wax itself is inedible, it’s easy to remove before serving. For DIY cheese enthusiasts, food-grade wax can be melted and applied in thin layers to homemade cheeses, ensuring even coverage for optimal preservation.

Artificial rinds, though less common, are designed for convenience or aesthetics. These include plastic-coated cheeses or those treated with preservatives to extend shelf life. While they lack the complexity of natural or bloomy rinds, they’re practical for mass-produced varieties. If you’re prioritizing flavor and authenticity, opt for cheeses with natural or bloomy rinds, but don’t dismiss artificial rinds entirely—they have their place in busy kitchens or as travel-friendly options.

In summary, the rind is more than just the cheese’s exterior—it’s a testament to its journey from milk to maturity. Whether natural, bloomy, waxed, or artificial, each rind type contributes to the cheese’s character, offering a sensory experience that begins long before the first bite. By recognizing these distinctions, you’ll not only select cheese with confidence but also elevate your culinary creations.

Effective Tips to Absorb Excess Grease from Cheesy Dishes

You may want to see also

Rind Formation: Bacteria, mold, or wax applied during cheese production creates the outer layer

The outer layer of cheese, often referred to as the rind, is a complex and fascinating aspect of cheese production. Rind formation is a deliberate process, involving the application of bacteria, mold, or wax during cheese production. This process not only creates a protective barrier but also contributes to the cheese's unique flavor, texture, and appearance. For instance, the rind of a Brie cheese is characterized by a white, velvety mold (Penicillium camemberti) that imparts a distinct earthy flavor, while the rind of a Gouda cheese is coated with a red or yellow wax that prevents moisture loss and mold growth.

From an analytical perspective, the choice of rind-forming agent depends on the desired cheese variety and its intended characteristics. Bacteria-based rinds, such as those found on washed-rind cheeses like Epoisses, are created by regularly brushing the cheese with a brine solution containing specific bacteria (e.g., Brevibacterium linens). This process encourages bacterial growth, resulting in a pungent aroma and a sticky, orange-hued rind. In contrast, mold-ripened cheeses like Camembert and Blue Cheese rely on the growth of specific molds (e.g., Penicillium roqueforti) to develop their distinctive flavors and textures. The mold spores are often introduced by spraying or dipping the cheese in a mold suspension, with a typical dosage of 1-5 million spores per milliliter of solution.

To create a wax-coated rind, cheese producers typically use food-grade wax, which is melted and applied to the cheese surface in multiple layers. The wax acts as a barrier, preventing moisture loss and inhibiting mold growth. For optimal results, the wax should be applied at a temperature of 140-160°F (60-70°C), with a thickness of 1-2 mm. It is essential to ensure that the cheese is properly dried and cooled before waxing, as moisture can become trapped beneath the wax, leading to spoilage. Additionally, the wax should be removed before consuming the cheese, as it is not edible.

A comparative analysis of rind formation techniques reveals that each method has its advantages and disadvantages. Bacteria-based rinds offer a wide range of flavors and textures but require careful monitoring to prevent unwanted bacterial growth. Mold-ripened rinds provide a distinctive character but can be challenging to control, as mold growth is highly dependent on environmental conditions. Wax-coated rinds, on the other hand, offer excellent protection against moisture loss and mold growth but can be labor-intensive and require specialized equipment. For home cheesemakers, a simple alternative to wax is to use a cloth bandage, which allows the cheese to breathe while still providing some protection.

In practice, understanding rind formation is crucial for cheese producers and enthusiasts alike. By manipulating the rind-forming process, producers can create a vast array of cheese varieties with unique characteristics. For example, a young cheese with a thin, delicate rind will have a milder flavor and softer texture compared to an aged cheese with a thick, hardened rind. To appreciate the nuances of rind formation, consider the following practical tips: when purchasing cheese, inspect the rind for signs of mold or bacterial growth, and ask the cheesemonger about the production process. When storing cheese, ensure that it is properly wrapped to prevent moisture loss and mold growth, and consider using a cheese paper or waxed cloth to maintain optimal humidity levels. By mastering the art of rind formation, cheese producers and enthusiasts can unlock a world of flavors, textures, and aromas that make cheese one of the most fascinating and delicious foods on the planet.

Queso Quesadilla vs. Mexican Cheese: Unraveling the Melty Mystery

You may want to see also

Edibility of Rind: Some rinds are edible, adding flavor, while others are removed before eating

The rind of a cheese is its outer layer, and its edibility varies widely depending on the type of cheese and its production method. For instance, the rind of a Brie or Camembert is not only edible but also prized for its creamy texture and earthy flavor, which complements the soft interior. In contrast, the wax coating on a Gouda or the thick, hard rind of a Parmesan are typically removed before consumption, as they can be unpalatable or difficult to digest. Understanding whether a rind is edible enhances both the culinary experience and safety.

When approaching a cheese with an edible rind, consider the aging process and intended purpose. Natural rinds, such as those on aged Cheddar or Alpine cheeses like Gruyère, are often consumed and contribute complex flavors developed through mold or bacteria cultures. However, these should be eaten in moderation, as their concentrated flavors and higher salt content can overwhelm a dish. For younger cheeses with bloomy rinds, like Brie, the entire piece can be consumed, but ensure the cheese is fresh and stored properly to avoid off-flavors.

For rinds that are not meant to be eaten, removal techniques matter. Hard, waxy, or heavily treated rinds (e.g., on Edam or some mass-produced cheeses) should be carefully trimmed with a sharp knife, leaving a thin layer of cheese beneath to avoid waste. Avoid consuming plastic or heavily waxed rinds, as these are non-edible coatings used for preservation. When in doubt, consult the cheese’s packaging or a cheesemonger for guidance on edibility.

Practical tips for handling rinds include pairing edible rinds with complementary foods. For example, the ash-coated rind of a Morbier pairs well with crusty bread, while the washed rind of an Époisses can be balanced with acidic accompaniments like pickled vegetables. For non-edible rinds, repurpose them by adding them to soups or stocks to infuse dishes with cheesy flavor. Always store cheeses properly—wrapped in wax or parchment paper, not plastic—to maintain rind integrity and prevent mold contamination.

In summary, the edibility of a cheese rind is a nuanced aspect of cheese appreciation. Edible rinds enhance flavor and texture, while non-edible rinds require thoughtful removal. By understanding these distinctions, you can maximize enjoyment and minimize waste, turning every cheese experience into an informed and delightful one.

Cheese Stick Protein Content: Uncovering the Nutritional Value Inside

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Rind Function: Protects cheese from spoilage, influences texture, and contributes to flavor development

The rind of a cheese is its unsung hero, a protective barrier that shields the delicate interior from the outside world. This outer layer, often overlooked, plays a critical role in preserving the cheese's integrity. Acting as a natural defense, the rind prevents harmful bacteria and mold from penetrating the cheese, significantly reducing the risk of spoilage. For instance, the thick, wax-coated rind of a Gouda or the hard, crusty exterior of a Parmesan create an environment that slows down the growth of unwanted microorganisms, ensuring the cheese remains safe to consume for extended periods. Without this protective function, even the most carefully crafted cheeses would succumb to decay far more rapidly.

Beyond its role as a guardian, the rind actively influences the cheese's texture. During aging, the rind regulates moisture levels, determining whether the cheese inside becomes creamy, crumbly, or firm. Soft-ripened cheeses like Brie, with their bloomy white rinds, allow for a slow, even distribution of moisture, resulting in a velvety interior. In contrast, hard cheeses like Cheddar develop a drier texture as their rinds restrict moisture loss more aggressively. This interplay between rind and interior is a delicate balance, one that cheesemakers manipulate through techniques like washing, brushing, or waxing to achieve the desired consistency.

Perhaps most fascinating is the rind's contribution to flavor development. As cheese ages, the rind becomes a hub of microbial activity, fostering the growth of beneficial bacteria and molds that break down proteins and fats into complex flavor compounds. For example, the pungent, earthy notes of a washed-rind cheese like Époisses arise from the bacteria cultivated on its surface. Similarly, the nutty, caramelized flavors of aged Alpine cheeses are often enhanced by their natural rinds, which concentrate sugars and amino acids over time. This transformative process turns the rind from a mere protective layer into an active participant in the cheese's sensory profile.

Practical considerations for home cheesemakers and enthusiasts underscore the rind's importance. When crafting cheese, selecting the right rind treatment—whether natural, waxed, or ash-coated—can dramatically alter the final product. For instance, a thin, natural rind on a Camembert encourages the growth of Penicillium camemberti, essential for its signature flavor and texture. Conversely, waxing a cheese like a Cheddar halts further rind development, preserving its sharpness. Understanding these nuances allows for greater control over the aging process, enabling both professionals and hobbyists to tailor cheeses to specific tastes and textures.

In conclusion, the rind is far more than the outer shell of a cheese; it is a dynamic, multifunctional component that safeguards, shapes, and enhances the cheese within. By protecting against spoilage, dictating texture, and contributing to flavor complexity, the rind exemplifies the intricate artistry of cheesemaking. Whether enjoyed as part of the cheese or removed before serving, its role is indispensable, making it a subject worthy of appreciation and study in the world of fromage.

Is Cheese High in Salt? Uncovering the Sodium Content in Your Favorite Dairy

You may want to see also

Rindless Cheese: Fresh cheeses like mozzarella or ricotta lack a rind due to minimal aging

Fresh cheeses like mozzarella and ricotta stand apart in the dairy aisle due to their absence of a rind, a characteristic directly tied to their minimal aging process. Unlike aged cheeses such as cheddar or Gruyère, which develop a protective outer layer over weeks or months, fresh cheeses are consumed shortly after production. This lack of aging means there’s no time for bacteria or mold to cultivate a rind, leaving the cheese with a uniformly soft, moist texture throughout. For home cooks, this makes fresh cheeses ideal for applications where a smooth, meltable consistency is desired, such as in salads, pizzas, or desserts.

The production process of rindless cheeses is deliberately swift, often completed within hours or days. Mozzarella, for instance, is stretched and kneaded in hot water before being shaped and cooled, a method known as pasta filata. Ricotta, on the other hand, is made by reheating whey left over from other cheese production, causing proteins to coagulate into soft curds. These techniques prioritize freshness and simplicity, ensuring the cheese retains its delicate flavor and texture. However, this also means rindless cheeses have a shorter shelf life, typically lasting only 1–2 weeks when refrigerated, compared to months for aged varieties.

From a culinary perspective, the absence of a rind in fresh cheeses offers both advantages and limitations. Without a rind to act as a barrier, these cheeses absorb flavors readily, making them excellent candidates for marinades or infusions. For example, soaking mozzarella in olive oil with herbs and garlic enhances its taste without altering its structure. Conversely, their softness and moisture content make them unsuitable for grilling or baking as standalone items, as they lack the structural integrity to hold their shape under heat. Pairing them with firmer ingredients, like crusty bread or crisp vegetables, can balance their texture in dishes.

For those looking to experiment with rindless cheeses, storage and handling are critical. Always store them in their original packaging or an airtight container to prevent them from drying out or absorbing refrigerator odors. If using in recipes, pat them dry with a paper towel to remove excess moisture, which can dilute flavors or affect consistency. When substituting fresh cheeses in recipes calling for aged varieties, adjust cooking times and methods accordingly—for instance, using ricotta in lasagna requires layering it with other ingredients to prevent sogginess. By understanding these nuances, even novice cooks can elevate their dishes with the unique qualities of rindless cheeses.

Perfect Philly Cheese Steak: Beef Seasoning Tips for Authentic Flavor

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The outside of a cheese is commonly referred to as the rind or crust.

Yes, many cheese rinds are edible, but it depends on the type of cheese. Some rinds are meant to be eaten, while others are better removed.

The rind serves as a protective barrier, preventing moisture loss and controlling the growth of bacteria and mold during aging.

No, not all cheese rinds are edible. Hard, waxed, or heavily molded rinds are often removed before consumption, while softer, natural rinds are typically safe to eat.