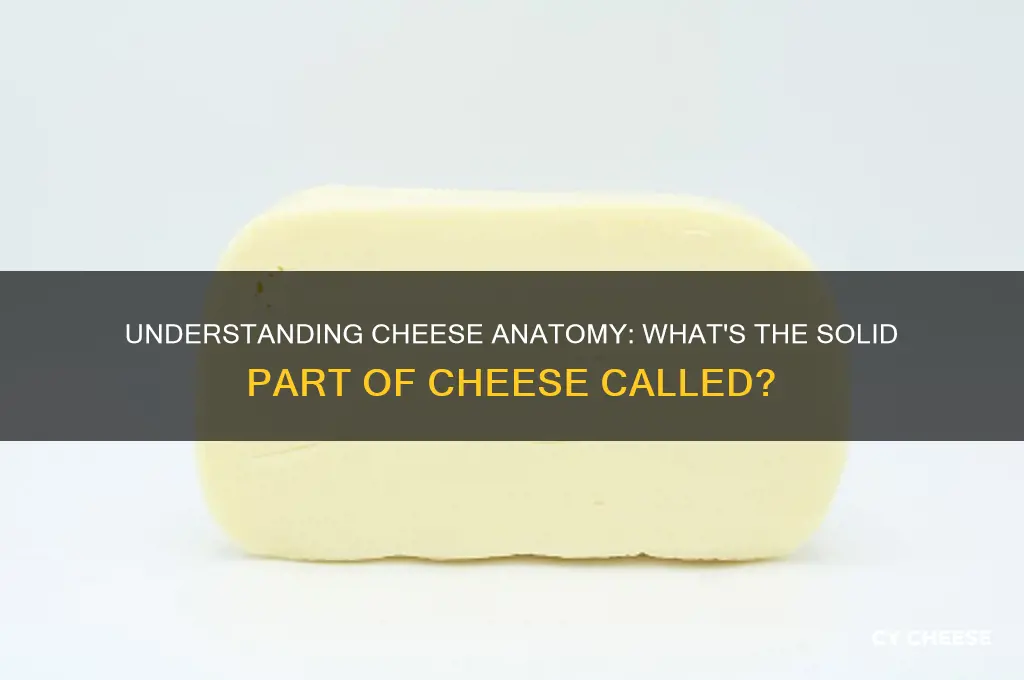

The solid part of cheese, often referred to as the curd, is the result of the coagulation of milk proteins (primarily casein) during the cheese-making process. This occurs when milk is treated with rennet or acid, causing it to separate into curds (the solid mass) and whey (the liquid). The curd is then pressed, aged, and sometimes heated to develop the texture, flavor, and structure characteristic of different cheese varieties. Understanding the curd is essential to appreciating the science and artistry behind cheese production.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Curd Formation: Milk coagulates into curds, the solid part of cheese, through enzymatic action

- Curd Texture: Curds can be soft, crumbly, or firm, depending on cheese type and process

- Curd vs. Whey: Curds are solids; whey is liquid separated during cheese making

- Curd Pressing: Curds are pressed to remove moisture, shaping the final cheese

- Curd Aging: Curds mature over time, developing flavor, texture, and character

Curd Formation: Milk coagulates into curds, the solid part of cheese, through enzymatic action

Milk, a liquid rich in proteins and fats, undergoes a remarkable transformation when it coagulates into curds—the solid foundation of cheese. This process, driven by enzymatic action, is both a scientific marvel and a culinary cornerstone. At its core, curd formation relies on the interaction between milk proteins, primarily casein, and enzymes like rennet or microbial transglutaminase. When these enzymes are introduced, they catalyze the breakdown of kappa-casein, a protein that stabilizes milk’s liquid structure. This breakdown allows calcium to bridge the casein micelles, forming a network that traps milk fats and solids, resulting in the solid curds.

To initiate curd formation, precise conditions are essential. Milk is typically heated to around 30°C (86°F), an optimal temperature for enzymatic activity. For example, rennet, a traditional enzyme derived from animal sources, is added at a dosage of 1:10,000 (0.1 mL per liter of milk). Alternatively, microbial rennet or acid-producing bacteria can be used, especially in vegetarian or artisanal cheese-making. The milk must remain undisturbed for 30–60 minutes to allow the enzyme to act fully. Over-stirring or incorrect temperature can hinder coagulation, emphasizing the need for careful control.

Comparing enzymatic coagulation to acid-induced curdling highlights its efficiency. While acid (like lemon juice or vinegar) can also form curds by denaturing proteins, enzymatic action is more precise and yields a firmer, more consistent texture. This is why cheeses like Cheddar or Parmesan rely on rennet, while fresh cheeses like ricotta often use acid. The choice of method directly impacts the cheese’s final characteristics, from moisture content to flavor profile.

Practical tips for home cheese-making underscore the importance of patience and precision. Always use high-quality, unpasteurized milk if possible, as pasteurization can affect protein structure. If using rennet, store it in a cool, dry place to preserve its potency. For beginners, start with simple cheeses like paneer or mozzarella, which require minimal equipment and offer immediate results. Observing the curd’s texture and consistency during formation is key—it should be firm but not rubbery, indicating successful enzymatic action.

In essence, curd formation is a delicate balance of science and art. By understanding the enzymatic process and mastering its variables, cheese-makers can transform humble milk into a diverse array of solids, each with its own unique character. Whether in a professional dairy or a home kitchen, this fundamental step remains the gateway to the world of cheese.

Effective Tips for Removing Stuck-On Eggs and Cheese from Pots

You may want to see also

Curd Texture: Curds can be soft, crumbly, or firm, depending on cheese type and process

The solid part of cheese, known as the curd, is the foundation of every cheese variety. Its texture—soft, crumbly, or firm—is a direct result of the cheese type and the processes involved in its creation. Understanding curd texture is essential for both cheese makers and enthusiasts, as it influences flavor, mouthfeel, and culinary applications.

Consider the contrast between fresh mozzarella and aged cheddar. Mozzarella’s curds are stretched and kneaded, resulting in a soft, pliable texture ideal for melting on pizzas or layering in caprese salads. In contrast, cheddar undergoes a cheddaring process where curds are stacked, cut, and turned, leading to a firm, crumbly texture that holds its shape in sandwiches or on a cheese board. These differences highlight how processing techniques directly shape curd texture.

For home cheese makers, controlling curd texture requires precision. Soft curds, like those in ricotta, are achieved by gently coagulating milk at lower temperatures (around 86°F or 30°C) and avoiding excessive stirring. Crumbly curds, as seen in feta, result from higher cooking temperatures (up to 190°F or 88°C) and cutting the curd into smaller pieces. Firm curds, such as those in Gruyère, demand extended pressing times (up to 24 hours) and higher cooking temperatures (around 195°F or 90°C). Each step must be carefully monitored to achieve the desired outcome.

From a culinary perspective, curd texture dictates a cheese’s versatility. Soft curds are best for spreading or blending into dishes, while crumbly curds add texture to salads or pastries. Firm curds excel in applications requiring structural integrity, such as grating over pasta or slicing for sandwiches. Pairing cheese with the right dish becomes intuitive when its curd texture is understood.

In essence, curd texture is not just a characteristic but a deliberate outcome of cheese making. Whether soft, crumbly, or firm, it reflects the interplay of technique, temperature, and time. Mastering this aspect unlocks a deeper appreciation for cheese and its endless possibilities in the kitchen.

Trader Joe's Pub Cheese Disappearance: What Happened to the Fan Favorite?

You may want to see also

Curd vs. Whey: Curds are solids; whey is liquid separated during cheese making

Cheese making is a fascinating process that transforms milk into a solid, edible delight. At the heart of this transformation lies the separation of milk into two primary components: curds and whey. Curds are the solid part of cheese, while whey is the liquid byproduct. Understanding this distinction is crucial for anyone interested in cheese production or its nutritional value.

Analytical Perspective:

During cheese making, milk is coagulated using enzymes (like rennet) or acids, causing it to separate into curds and whey. Curds are rich in protein, fat, and minerals, forming the basis of cheese. Whey, on the other hand, is predominantly water with lactose, vitamins, and trace proteins. This separation is not just a physical process but a chemical one, where the milk’s structure is altered to create a solid mass. For example, in cheddar cheese production, the curds are cut, heated, and pressed to expel whey, concentrating the solids into the final product.

Instructive Approach:

To observe this process at home, try making simple ricotta cheese. Heat milk to 180°F (82°C), add vinegar or lemon juice (1-2 tablespoons per gallon of milk), and watch as curds form and float in whey. Strain the mixture through cheesecloth to separate the solids (curds) from the liquid (whey). The curds can be salted and shaped into cheese, while whey can be saved for smoothies or baking. This hands-on experiment highlights the tangible difference between the two components.

Comparative Insight:

While curds are the star of cheese, whey is no less valuable. Curds provide the texture and flavor we associate with cheese, but whey is a nutritional powerhouse, often used in protein supplements and animal feed. For instance, whey protein isolate contains 90-95% protein by weight, making it a popular choice for fitness enthusiasts. In contrast, curds are more versatile in culinary applications, from melting mozzarella to crumbly feta.

Descriptive Takeaway:

Imagine a freshly made cheese: the curds are the dense, creamy, or crumbly part you bite into, while whey is the liquid that drains away during production. This separation is the cornerstone of cheese making, turning a simple ingredient like milk into a diverse array of products. Whether you’re a cheese maker, a food enthusiast, or a health-conscious consumer, understanding curds and whey unlocks a deeper appreciation for this ancient craft.

Who Ate the Cheese? Unraveling the Mystery in Diary of a Wimpy Kid

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Curd Pressing: Curds are pressed to remove moisture, shaping the final cheese

The solid part of cheese, often referred to as the curd, is the foundation of every cheese variety. Curd formation is a critical step in cheesemaking, where milk proteins coagulate and separate from the liquid whey. However, the curd itself is not yet cheese—it’s a fragile, moisture-rich mass that requires further transformation. This is where curd pressing comes into play, a process that removes excess moisture, consolidates the curd, and shapes it into the final cheese form. Without pressing, many cheeses would lack the desired texture, structure, and longevity.

Analytical Perspective: Curd pressing is both a science and an art. The pressure applied and the duration of pressing vary depending on the cheese type. For example, hard cheeses like Cheddar or Parmesan require higher pressure (often 50–100 pounds per square inch) and longer pressing times (up to 24 hours) to achieve their dense, low-moisture structure. In contrast, softer cheeses like Brie or Camembert are pressed gently, if at all, to retain their creamy texture. The goal is to expel enough whey to create a stable matrix while preserving the desired moisture content, which directly influences flavor and mouthfeel.

Instructive Approach: To press curds effectively, start by placing the curd in a mold lined with cheesecloth. Apply weight gradually, increasing it over time to avoid crushing the curd. For home cheesemakers, common weights include bricks, dumbbells, or even heavy cans. Pressing should be done at room temperature or in a cool environment to prevent spoilage. Monitor the process closely—too much pressure can expel too much whey, resulting in a dry, crumbly texture, while too little leaves the cheese soft and prone to spoilage. Aim for a balance that aligns with the cheese’s intended style.

Comparative Insight: Curd pressing distinguishes cheese from other dairy products like yogurt or ricotta, which retain more moisture. For instance, ricotta is simply drained, not pressed, giving it a grainy, delicate texture. In contrast, pressing transforms curds into a cohesive mass, allowing for aging and flavor development. Consider the difference between fresh mozzarella (lightly pressed) and aged Gouda (heavily pressed)—the latter’s firmness and complexity are direct results of rigorous pressing and subsequent aging.

Descriptive Takeaway: Imagine the curd as a sponge, holding onto whey until pressure squeezes it out. As pressing progresses, the curd tightens, becoming denser and more uniform. This process not only shapes the cheese but also concentrates its proteins and fats, intensifying flavor. The final product is a testament to the precision of curd pressing—a solid, sliceable cheese that ranges from soft and supple to hard and brittle, all depending on how much moisture was removed. Without this step, the curd would remain a loose, unrecognizable mass, far from the cheese we know and love.

Ham and Cheese Sandwich: Homogeneous or Heterogeneous? Exploring the Science

You may want to see also

Curd Aging: Curds mature over time, developing flavor, texture, and character

The solid part of cheese, known as the curd, is the foundation of every cheese variety. Curd aging is a transformative process where these solids evolve from a bland, rubbery mass into a complex, flavorful centerpiece. This maturation is not merely a waiting game but a delicate interplay of time, environment, and microbial activity. Understanding this process reveals why aged cheeses command such reverence in culinary circles.

Consider the journey of a young curd. Freshly formed, it is mild and moist, with a texture akin to soft tofu. As it ages, enzymes and bacteria break down proteins and fats, releasing compounds that deepen flavor and alter texture. For instance, cheddar curds, when aged for 6 to 12 months, develop a sharp tang and crumbly consistency, while a 24-month aging process yields a brittle texture and intense, nutty notes. This progression underscores the principle that time is not just a measure but a sculptor of cheese character.

Practical aging requires precision. Ideal conditions include a cool, humid environment—typically 50–55°F (10–13°C) with 85–90% humidity. Hard cheeses like Parmesan benefit from longer aging, often 12 to 36 months, while softer varieties like Camembert mature in just 3 to 4 weeks. Turning the cheese periodically prevents mold dominance on one side and ensures even moisture distribution. For home aging, a wine fridge or a dedicated cheese cave with temperature and humidity controls is ideal. Avoid common pitfalls like excessive warmth, which accelerates spoilage, or low humidity, which leads to dry, cracked rinds.

The science behind curd aging is as fascinating as it is practical. Microorganisms, such as *Penicillium* molds and lactic acid bacteria, metabolize lactose and proteins, producing amino acids, organic acids, and esters that contribute to flavor complexity. For example, the eyes in Swiss cheese result from carbon dioxide bubbles produced by *Propionibacterium freudenreichii*. This microbial symphony is why artisanal cheesemakers guard their starter cultures and aging techniques as closely as family secrets.

In essence, curd aging is an art grounded in science, a process that elevates cheese from a simple dairy product to a culinary masterpiece. Whether you’re a cheesemaker or enthusiast, appreciating this transformation enriches your understanding of how time and care craft flavor, texture, and character. The next time you savor a slice of aged cheese, remember: every bite tells a story of patience and precision.

Understanding the Red Stain on Munster Cheese: Causes and Facts

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The solid part of cheese is called the curd.

The curd is formed by coagulating milk, typically using rennet or acid, which separates the milk into solid curds and liquid whey.

Yes, the curd is the primary edible part of cheese, while the whey is often discarded or used in other products.

No, the texture and characteristics of the curd vary depending on the type of cheese, milk used, and production methods.