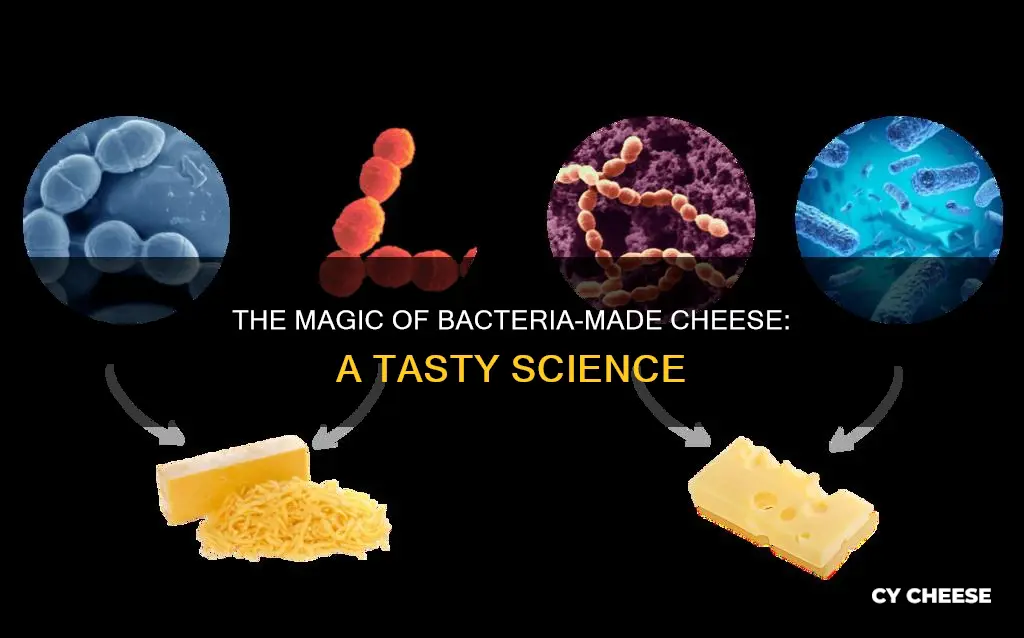

Cheese is a milk-derived food that serves as a means of preserving milk and its remarkable nutritive properties. It is made from four ingredients: milk, salt, rennet (or some other coagulant), and microbes. The magic that is cheese happens because of the presence of microbes.

Microorganisms found in cheese are responsible for much of the uniqueness and character that we all know and love. The bacteria, molds, and yeasts that find their way into cheese can be added intentionally by the cheesemaker or affineur. However, a lot of microbes are introduced into the cheese without any direct decision-making from the cheesemaker/affineur. This is where a cheese takes on its so-called terroir. Microbes native to the milk will be carried over to the cheese, and as cheese is being made and aged, many ambient organisms find their way in.

Microbes are introduced into cheese at every step in the cheese-making process. Lactic acid bacteria are the microbes that are added to the milk very early in the cheese-making process that induce the fermentation process. They are often called starter cultures as they play the main role in converting the basic milk sugar, lactose, into lactic acid, a step that lowers cheese pH and makes the cheese inhospitable to many spoilage organisms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Microorganisms | <co: 0,1,2,3,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,14 |

Explore related products

$17.97

What You'll Learn

Lactic acid bacteria

There are two main families of LAB: lactococci, which are sphere-shaped, and lactobacilli, which are rod-shaped. Streptococci can also be important in the initial stages of cheesemaking, and are very important in yoghurt-making.

LAB are grown by scientists in laboratories and sold in sachets as 'starter cultures'. They are usually added to the milk at the beginning of cheesemaking so they can kickstart the process. However, in traditional cheesemaking, a natural fermentation process is used, where a small quantity of whey from a previous batch is added to the milk.

Cheese-making is an ancient process, with evidence of it being performed since the late Stone Age. However, only recently have scientists begun to study the microbial nature of cheese and the role of bacteria in creating its distinctive flavours and textures.

LAB are important in cheese processing because they:

- Increase food safety by releasing lactic acid and bacteriocins, which prevent the growth of unwanted bacteria

- Produce aromas and flavours, and accelerate the maturation process via their proteolytic and lipolytic activities

- Improve food texture by releasing polysaccharides that increase viscosity and firmness, and reduce susceptibility to syneresis

- Can be used to deliver polyunsaturated fatty acids and vitamins, increasing the nutritional value of cheese

- Contribute to health-enhancing bioactive peptides, improving absorption in the intestinal tract, stimulating the immune system, and exerting antihypertensive and antithrombotic effects

Cheese for Chili Dogs: Melty, Tangy, and Spicy Combos

You may want to see also

Propionic acid bacteria

Propionic acid fermentation can occur spontaneously or can be achieved by a culture of selected propionic acid bacteria. The most commonly used propionic acid bacteria in cheese production is Propionibacterium freudenreichii, which is added to the milk at an inoculation dose of 10³–10⁴ cfu/mL.

PAB are anaerobic to aerotolerant and grow optimally at a pH of 6–7, with a minimum pH of 4.6 and maximum of 8.5. They are sensitive to salt, with growth impaired by the addition of 6% NaCl. PAB are also slow-growing, with generation times of approximately 5 hours under optimal conditions.

PAB are Gram-positive, nonmotile, nonsporulating bacteria. They can appear as short rods, coccoid, bifid, branched, or filamentous and may occur single, paired, or in short chains with V or Y configurations.

DelMonte's 4-Cheese Sauce: Unraveling the Cheesy Mystery

You may want to see also

Blue and white moulds

Blue Moulds

Blue moulds are responsible for the unique flavour, texture, and colour of blue cheeses. They are added to the milk or curds during the early stages of the cheese-making process. The two main species of blue mould are Penicillium roqueforti and Penicillium glaucum. These moulds can grow in low-oxygen environments, making them well-suited for the small cracks in ripening cheese. Cheesemakers pierce and inoculate channels in the cheese to encourage the growth of these moulds. Examples of blue cheeses include Roquefort, Stilton, Gorgonzola, and Cabrales.

White Moulds

White moulds are found on the outside of soft-ripened cheeses and are a subspecies of Penicillium camemberti (formerly known as Penicillium candidum). These moulds produce enzymes that break down the milk proteins in the curds, resulting in a ripened layer surrounding a firm interior. The flavour compounds produced by this breakdown have garlicky or earthy notes, but ammonia is also produced, so it is advisable to let these cheeses breathe to allow the ammonia to dissipate. Examples of cheeses with white moulds include Brie and Camembert.

Cheese and Corned Beef: The Perfect Pairing

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Smear bacteria

The most common type of smear bacteria is Brevibacterium linens, which is also commonly found on human skin and is responsible for foot odour. It produces a multitude of compounds, including those that give rise to the distinctive aroma of washed-rind cheeses.

Other common types of smear bacteria include:

- Corynebacterium casei

- Microbacterium gubbeenense

- Arthrobacter nicotianae

- Staphylococcus equorum

White Queso: Authentic Cheese or Modern Twist?

You may want to see also

Yeast

The sexual reproduction of yeasts is called 'teleomorph' and is considered the perfect form, while asexual reproduction, or 'anamorph', is considered the imperfect form.

Geotrichum Candidum, once considered a mould, is now categorised as a yeast. It develops in blue-veined cheeses, soft cheeses with washed or bloomy rinds, and uncooked pressed cheeses. The role of this yeast is to help develop the rinds of cheeses and to give the cheese its flavour (defined as the tactile, taste, and olfactory sensations that occur when we taste foods).

The four prominent yeasts used in cheese-making are:

- Debaryomyces: These have an abundance of lactose (milk sugar) and lactic acid. They are naturally present in milk and their role is to help make curds less acidic. They work well with other moulds and bacteria to give the cheese its texture and appearance during affinage.

- Kluyveromices: These are natural flavour enhancers and therefore play a crucial role in the development of flavour in cheese.

- Candida: When not present in excessive quantities, candida aids in our digestion and lives naturally in our intestines. They serve to ripen cheeses and make them less acidic.

- Geotrichum Candidum: As mentioned above, this yeast helps to develop the rinds of cheeses and to give the cheese its flavour. It can also act as a defence against Mucor, a mould that grows on surfaces and is harmless. Nevertheless, the development of this fungus breaks down the rinds of some cheeses.

The Cheeses That Make Mexican Food Delicious

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The most common types of bacteria used to make cheese are lactic acid bacteria, propionic acid bacteria, and smear bacteria.

Lactic acid bacteria are often called "starter cultures" as they play a main role in converting the basic milk sugar, lactose, into lactic acid. This process lowers the cheese's pH and makes the cheese inhospitable to spoilage organisms.

Propionic acid bacteria, specifically Propionibacter shermanii, are able to digest acetic acid and convert it to sharp, sweaty-smelling propionic acid and carbon dioxide. The carbon dioxide is what gives Emmental and other Swiss cheeses their characteristic "holes".

Smear bacteria are responsible for the strong smell of cheeses like Epoisses, Münster, and Limburger. They can't live in acidic or deoxygenated environments, so they are usually found on the surface of cheeses.