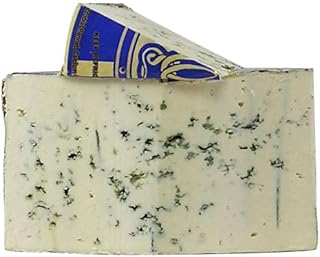

Blue cheese is made by mixing Penicillium roqueforti mould spores with milk. This mixture is then inoculated with salt, sugar, or both, and incubated for three to four days. The cheese gets its distinctive blue, blue-grey, or blue-green veins from the mould. In addition to P. roqueforti, blue cheese contains a variety of other microbes, including bacteria, yeasts, and fungi, which contribute to its unique characteristics and flavour.

Characteristics and Values of Microbes in Blue Cheese

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Microorganisms | Prokaryotic and eukaryotic microorganisms |

| Fungi | Penicillium roqueforti, Penicillium glaucum |

| Bacteria | Lactic acid bacteria (LAB), Lactococcus spp., Leuconostoc, Lactobacillus helveticus, Lactococcus lactis, Enterococcus faecalis, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus curvatus, Leuconostoc mesenteroides, Staphylococcus equorum, Staphylococcus sp., Brevibacterium linens |

| Yeast | Various species |

| Other compounds | Ketones, volatile compounds, spermidine, fatty acids, peptides, tyrosine crystals |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Blue cheese is made with the addition of edible moulds, specifically Penicillium roqueforti

- The mould spores are mixed with milk to begin the fermentation process

- Microbes are introduced at every step of the cheese-making process

- Microbes native to the milk are carried over to the cheese

- Ambient microbes are introduced as the cheese is aged

Blue cheese is made with the addition of edible moulds, specifically Penicillium roqueforti

The first phase of blue cheese production involves the culturing of suitable spore-rich inocula and fermentation. This is achieved by preparing a Penicillium roqueforti inoculum, which can be done through multiple methods. All methods, however, involve the use of a freeze-dried Penicillium roqueforti culture. This mould is washed from a pure culture agar plate and then frozen.

Once the Penicillium roqueforti inoculum is prepared, it is mixed with milk to begin the fermentation process. Salt, sugar, or both are added to autoclaved, homogenised milk through a sterile solution. This mixture is then inoculated with the mould and incubated for three to four days at 21–25 °C (70–77 °F). More salt and/or sugar is added, and aerobic incubation is continued for another one to two days. Alternatively, a fermentation medium can be created by mixing sterilised, homogenised milk and reconstituted non-fat solids or whey solids with sterile salt. A spore-rich Penicillium roqueforti culture is then added, along with modified milk fat, which is essential for rapid flavour development.

After the cheese forms into a solid shape, the cheesemaker pierces it with stainless steel needles to create pathways for air to flow and allow the mould veins to develop. The final step is ripening the cheese by ageing it. This process typically takes 60–90 days before the flavour of the cheese is typical and acceptable for marketing.

In addition to Penicillium roqueforti, blue cheese contains a complex microbial population, including lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and fungi. These microorganisms interact and succeed throughout the manufacturing and ripening processes, contributing to the final product's characteristics and quality.

Green Olives, Blue Cheese: Healthy or Indulgent?

You may want to see also

The mould spores are mixed with milk to begin the fermentation process

Blue cheese is made from cow, goat, sheep, or even buffalo milk, which may be raw or pasteurised. The milk is then mixed with mould spores to begin the fermentation process.

Firstly, salt, sugar, or both are added to autoclaved, homogenised milk via a sterile solution. This mixture is then inoculated with Penicillium roqueforti—a freeze-dried culture that gives blue cheese its distinctive blue veins. This solution is incubated for three to four days at 21–25 °C (70–77 °F), before more salt and/or sugar is added and then aerobic incubation is continued for an additional one to two days. Alternatively, sterilised, homogenised milk and reconstituted non-fat solids or whey solids are mixed with sterile salt to create a fermentation medium. A spore-rich Penicillium roqueforti culture is then added, followed by modified milk fat. This solution is prepared in advance by an enzyme hydrolysis of a milk fat emulsion. The addition of modified milk fat stimulates a progressive release of free fatty acids, which is essential for rapid flavour development in blue cheese.

After the curds have formed and been ladled into containers, the Penicillium roqueforti inoculum is sprinkled on top, along with Brevibacterium linens—the bacteria responsible for body odour. The curds are then knit into moulds to form cheese loaves with a relatively open texture. Whey drainage continues for 10–48 hours, with no pressure applied, and the moulds are inverted frequently to promote this process. Salt is then added to provide flavour and act as a preservative, with the cheese undergoing brine salting or dry salting for 24–48 hours.

The final step is ripening the cheese by ageing it. When the cheese is freshly made, there is little to no blue cheese flavour development. Usually, a fermentation period of 60–90 days is needed before the flavour of the cheese is typical and acceptable for marketing. The ripened cheese's final quality and shelf life largely depend on the enzymatic systems of the components of the microbiota, particularly on those of LAB, P. roqueforti, and yeast species.

Blue Cheese's Meaty Matches: A Foodie's Guide

You may want to see also

Microbes are introduced at every step of the cheese-making process

Blue cheese is made from cow, goat, sheep, or even buffalo milk, which may be raw or pasteurized. The milk is then mixed with a sterile solution of salt, sugar, or both. This mixture is then inoculated with Penicillium roqueforti, a common blue mold, and incubated for three to four days. More salt and/or sugar is added, and then aerobic incubation is continued for an additional one to two days. This process introduces microbes to the cheese, as the milk may contain microbes attached to the milking animals' teats, and the environment of the cheese-making facility may also contain microbes that can enter the cheese during production.

After incubation, the curds are ladled into containers to drain and form into a wheel of cheese. The Penicillium roqueforti inoculum is then sprinkled on top of the curds, along with Brevibacterium linens, a common smear bacterium. The curds are then knit in molds to form cheese loaves, and whey drainage is continued for 10-48 hours. This step further introduces microbes as the piercing of the cheese with stainless steel needles creates crevices that allow oxygen to interact with the cultures in the cheese and promote mold growth.

Salt is then added to the cheese to provide flavor and act as a preservative. The cheese is then aged for 60-90 days to develop its characteristic flavor. During this aging process, the cheese is exposed to the environmental microbes of the aging facilities, which can settle on the cheese as it matures. Additionally, the piercing of the cheese during the aging process further encourages mold growth by introducing oxygen.

The final product, blue cheese, is characterized by its blue veins, created by the development of the fungus Penicillium roqueforti. The complex microbial populations present in blue cheese, including bacteria, yeast, and fungi, contribute to its unique sensory characteristics, such as flavor, aroma, and texture. These microbes interact with each other and the environment, influencing the final quality and shelf life of the cheese.

The Origin Story of Blue Cheese: Animal Sources

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Microbes native to the milk are carried over to the cheese

Blue cheese is any cheese made with the addition of cultures of edible moulds, which create blue-green spots or veins throughout the cheese. Blue cheese is made with raw or pasteurised milk from cows, ewes, goats, or a mixture of them. Cow's milk is the most common variety worldwide.

The process of making blue cheese consists of six standard steps, with additional ingredients and processes to give the cheese its characteristic properties. The first phase of production involves preparing a Penicillium roqueforti inoculum, which is then mixed with milk to begin the fermentation process. After the cheese forms into a solid, cheesemakers pierce it with stainless steel needles to create airways for the blue veins of mould to develop.

The microbiota of blue cheeses consists of a wide array of prokaryotic and eukaryotic microorganisms. The acidification of the curd is dependent on lactococci and other lactic acid bacteria (LAB) species. The final quality and shelf life of the cheese depend on the enzymatic systems of the components of the microbiota, particularly LAB, P. roqueforti, and yeast species.

Blue Cheese Turning Green: What Does It Mean?

You may want to see also

Ambient microbes are introduced as the cheese is aged

The process of making blue cheese consists of six standard steps, but additional ingredients and processes are required to give this blue-veined cheese its particular properties. Blue cheese is made by mixing Penicillium roqueforti mold spores with milk. The mold spores are first prepared by washing them from a pure culture agar plate, which is then frozen. The mold spores are then mixed with milk to begin the fermentation process.

After the cheese forms into a solid shape, cheesemakers pierce it with stainless steel needles to create pathways for air to flow. These pathways are where the distinctive blue, blue-gray, or blue-green veins of mold will later develop. During the aging process, ambient microbes are introduced as the cheese is aged. These microbes are introduced into the cheese at every step of the cheese-making process. Microbes native to the milk will be carried over to the cheese, and as the cheese is being made and aged, many ambient organisms are introduced.

The final quality and shelf life of the cheese depend on the enzymatic systems of the components of the microbiota, particularly lactic acid bacteria (LAB), P. roqueforti, and yeast species. The most important biochemical process involved in blue-veined cheeses during ripening is proteolysis, with P. roqueforti being the main proteolytic agent. Lipolysis is also strong, originating in, among other compounds, ketones, which are the main aroma compounds in blue-veined cheeses.

Blue cheese contains a substance called spermidine, which has been linked to improved heart health and increased longevity in mice and rats. A 2018 review also noted that fermented dairy products contain lactic acid bacteria, fatty acids, and peptides that may help boost cognitive function and protect against age-related memory decline and dementia. However, overconsumption of blue cheese can add excess calories and saturated fat to the diet, increasing the risk of heart disease.

Preparing Blacksticks Blue Cheese: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The main microbe in blue cheese is the mold Penicillium roqueforti, which is added by cheesemakers to create the distinctive blue veins.

Blue cheese contains a variety of microbes, including bacteria, yeasts, and other molds. Some common microbes found in blue cheese include:

- Lactococcus spp.

- Leuconostoc

- Brevibacterium linens

- Lactobacillus helveticus

- Staphylococcus equorum

Blue cheese is made with the addition of cultures of edible molds, which create blue-green spots or veins. The cheesemaking process also introduces many ambient organisms, which contribute to the unique character of the cheese.

Yes, the microbes in blue cheese are safe for human consumption. Blue cheese is a nutrient-dense food that contains various vitamins, minerals, and natural compounds with potential health benefits. However, it should be consumed in moderation due to its high fat, calorie, and sodium content.