The United States maintains a significant cheese stockpile as part of its agricultural policy, primarily through the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC), which was established to support dairy farmers and stabilize market prices. This stockpile, often referred to as government cheese, originated in the 1980s when a surplus of milk led to excessive cheese production, prompting the government to purchase the excess to prevent market crashes and ensure fair prices for farmers. Over time, the stockpile has served multiple purposes, including providing food assistance to low-income families, schools, and international aid programs, while also acting as a buffer to manage supply and demand fluctuations in the dairy industry. Despite occasional criticism for its cost and inefficiency, the cheese stockpile remains a key tool in U.S. agricultural policy, balancing the interests of farmers, consumers, and the broader economy.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Purpose | Government price support for dairy farmers, market stabilization, and food assistance programs |

| Current Stockpile (as of 2023) | Approximately 1.4 billion pounds (635 million kg) |

| Primary Cheese Type | Cheddar and American cheese |

| Storage Locations | Cold storage facilities across the U.S., primarily in Wisconsin and other dairy-producing states |

| Cost to Taxpayers (Annual) | Around $20 million (for storage and maintenance) |

| Historical Peak Stockpile | Over 2 billion pounds in 2017 |

| Key Legislation | Agricultural Act of 1949 (permanent price support program) |

| Usage | Distributed to food banks, school lunch programs, and occasionally exported |

| Criticism | Inefficient use of taxpayer funds, distorts market prices, and contributes to food waste |

| Recent Trends | Stockpile has decreased due to increased domestic consumption and reduced government purchases |

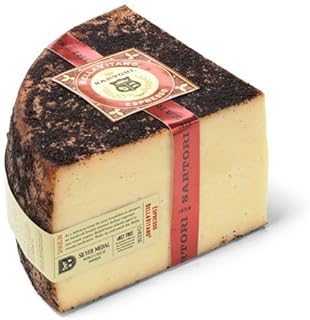

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Historical origins of cheese stockpiling

The U.S. cheese stockpile, often a subject of curiosity, traces its roots to the mid-20th century, a period marked by agricultural surplus and economic instability. In the 1930s, the Great Depression left farmers with excess dairy products, prompting the government to intervene. The Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933 authorized the purchase of surplus commodities, including cheese, to stabilize prices and support struggling farmers. This marked the beginning of a practice that would evolve into a long-term strategy for managing dairy production. By 1935, the government had amassed over 200 million pounds of cheese, stored in warehouses across the country, setting the stage for decades of stockpiling.

During World War II, the cheese stockpile took on a new purpose. As the nation mobilized for war, the government used stored cheese to feed troops and allies, ensuring a steady supply of protein-rich food. This wartime necessity reinforced the idea that stockpiling was not just a solution for surplus but also a strategic reserve. After the war, the practice continued under the Agricultural Act of 1949, which formalized price supports and surplus purchases. By the 1950s, the government was buying millions of pounds of cheese annually, often distributing it through school lunch programs and foreign aid initiatives. This dual role—stabilizing markets and providing food security—cemented the stockpile’s place in U.S. agricultural policy.

The 1980s brought the cheese stockpile into the public eye, as it grew to unprecedented levels. By 1984, the government held over 500 million pounds of cheese, valued at $200 million, due to overproduction and declining demand. This surplus became a symbol of inefficiencies in farm policy, sparking debates about the role of government in agriculture. Critics argued that stockpiling distorted markets, while supporters maintained it protected farmers from price crashes. The government responded by selling excess cheese at discounted rates and exploring new uses, such as processing it into other dairy products. This era highlighted the challenges of balancing farmer support with market dynamics.

Today, the historical origins of cheese stockpiling offer lessons for modern agricultural policy. The practice began as a crisis response but evolved into a complex system with unintended consequences. While it provided stability for farmers and food for those in need, it also created inefficiencies and public scrutiny. Understanding this history is crucial for policymakers seeking to reform dairy programs. By studying past successes and failures, they can develop strategies that support farmers without relying on massive stockpiles, such as incentivizing diversification or improving demand forecasting. The cheese stockpile’s legacy reminds us that solutions born of necessity must adapt to changing times.

Mastering Aged Cheese Storage: Tips for Keeping Store-Bought Cheese Fresh at Home

You may want to see also

Economic impact on dairy farmers and markets

The U.S. cheese stockpile, often a subject of curiosity, serves as a buffer against market volatility, directly influencing dairy farmers and markets. When milk prices drop, the government steps in, purchasing cheese to stabilize incomes for farmers. This mechanism, part of the Dairy Product Price Support Program, ensures producers receive a minimum price for their milk, preventing financial distress during oversupply. However, this intervention creates a ripple effect: while farmers benefit from price stability, the accumulation of cheese can distort market signals, potentially discouraging innovation and efficiency in the long term.

Consider the market dynamics: excess cheese in storage can depress prices when released, affecting both domestic and international markets. For instance, in 2016, the U.S. held over 1.4 billion pounds of cheese, a record high, which led to lower prices for dairy producers. This oversupply not only reduces profitability for farmers but also impacts processors and retailers, who must navigate fluctuating costs. Internationally, the stockpile can undermine U.S. competitiveness, as exporting surplus cheese at discounted rates may undercut global prices, straining trade relationships.

From a farmer’s perspective, the stockpile is a double-edged sword. While it provides a safety net during downturns, reliance on government intervention can stifle adaptability. Farmers may become less inclined to diversify their operations or invest in technology to improve efficiency, knowing the government will absorb excess production. This dependency risks long-term sustainability, as the dairy industry must evolve to meet changing consumer demands, such as the rise of plant-based alternatives.

To mitigate these challenges, policymakers could explore alternative strategies. For example, incentivizing dairy farmers to produce value-added products, like specialty cheeses or whey-based supplements, could reduce reliance on bulk commodities. Additionally, promoting exports through trade agreements or marketing campaigns could help absorb surplus production without distorting domestic markets. Such measures would not only stabilize incomes but also foster a more resilient and dynamic dairy sector.

In conclusion, the cheese stockpile’s economic impact on dairy farmers and markets is complex, offering both stability and unintended consequences. By balancing short-term support with long-term strategies, the industry can navigate market volatility while encouraging innovation and sustainability. Farmers, policymakers, and market participants must collaborate to ensure the dairy sector remains robust in an ever-changing economic landscape.

How Aging Transforms Cheese: Texture, Flavor, and Complexity Explained

You may want to see also

Government policies and subsidies driving stockpiles

The U.S. government’s cheese stockpile, once a symbol of agricultural surplus, is no accident. It’s the direct result of policies designed to stabilize farm incomes and manage market volatility. The Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933 and subsequent Farm Bills introduced price supports and subsidies, ensuring farmers a minimum price for their milk. When dairy production exceeded demand, the government stepped in, purchasing the surplus to prevent price crashes. This mechanism, while protective for farmers, led to the accumulation of billions of pounds of cheese in government-owned warehouses.

Consider the practical mechanics: When milk prices drop below the federally guaranteed level, the government buys cheese at a set price, effectively removing it from the market. This cheese isn’t always distributed efficiently; it often sits in storage, costing taxpayers millions annually. For instance, in 2016, the stockpile reached 1.4 billion pounds—enough to supply every American with 4.5 pounds of cheese. Critics argue this system incentivizes overproduction, as farmers know the government will absorb excess supply. Yet, proponents claim it prevents rural economic collapse by ensuring stable incomes for dairy farmers.

To understand the subsidy’s impact, compare it to a dosage: too little, and farmers face financial ruin; too much, and stockpiles balloon. The government’s role is akin to a regulator, adjusting the "dosage" of subsidies and purchases to balance farmer support and market efficiency. However, this system often fails to address root issues, such as declining domestic milk consumption and global market competition. Instead, it creates a cycle where surpluses are stored rather than sold, leading to inefficiencies and waste.

A persuasive argument emerges when examining alternatives. Countries like New Zealand, with less interventionist policies, rely on market forces to manage dairy production. Their farmers adapt to demand fluctuations without government stockpiling. In contrast, the U.S. system, while protective, fosters dependency on federal support. For taxpayers, this translates to higher costs and questionable returns. For consumers, it means artificially low prices that mask the true environmental and economic costs of overproduction.

Instructively, breaking this cycle requires policy reform. One step is to cap subsidies and redirect funds toward sustainable farming practices or export incentives. Another is to improve distribution channels, ensuring surplus cheese reaches food banks rather than warehouses. Caution must be taken, however, to avoid abrupt changes that could devastate rural communities. A phased approach, combining reduced subsidies with targeted support for diversification, could strike a balance. The takeaway? Government policies, while well-intentioned, have unintended consequences. Addressing the cheese stockpile issue demands a reevaluation of these policies to align with modern agricultural and economic realities.

Perfect Cheese Portions: How Much for 23 Sandwiches?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental consequences of excess cheese storage

The U.S. cheese stockpile, a relic of agricultural subsidies, has ballooning environmental consequences that extend far beyond the warehouse walls. Storing excess cheese requires massive refrigeration, consuming energy equivalent to powering thousands of homes annually. For every pound of cheese stored, approximately 0.5 kWh of electricity is used daily, contributing to greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuel-dependent power plants. This energy-intensive process exacerbates climate change, particularly when stockpiles reach record levels, as seen in 2017 when reserves topped 1.4 billion pounds.

Consider the lifecycle of cheese storage: refrigeration units emit hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), potent greenhouse gases with a global warming potential up to 14,800 times that of CO₂. While the Kigali Amendment aims to phase out HFCs, current stockpiles rely on older, inefficient systems. Additionally, cheese production itself is resource-intensive, requiring 2,500 gallons of water per pound of cheese. When excess cheese is stored indefinitely, the embedded water and energy are effectively wasted, compounding the environmental toll.

From a comparative perspective, the environmental impact of cheese stockpiles rivals that of other food waste. While rotting produce emits methane in landfills, cheese storage generates a different but equally harmful footprint. For instance, the carbon footprint of storing 1 ton of cheese for a year is roughly equivalent to driving a car 6,000 miles. Unlike perishable fruits or vegetables, cheese’s longevity in storage does not mitigate its environmental impact; instead, it prolongs the inefficiency of resource use.

To mitigate these consequences, actionable steps can be taken. First, policymakers could redirect subsidies toward sustainable dairy practices, incentivizing farmers to produce only what the market demands. Second, investing in energy-efficient refrigeration technologies, such as CO₂-based systems, could reduce emissions by up to 60%. Finally, consumers can play a role by reducing cheese consumption and supporting local, low-carbon dairy alternatives. These measures, while not exhaustive, offer a starting point to address the hidden environmental costs of excess cheese storage.

Quick Tips for Softening Mascarpone Cheese to Room Temperature

You may want to see also

Modern challenges and future of cheese reserves

The U.S. cheese stockpile, once a symbol of agricultural stability, now faces unprecedented challenges. Fluctuating milk prices, shifting consumer preferences, and global trade dynamics have turned this reserve from a safety net into a logistical headache. In 2020, the stockpile peaked at 1.4 billion pounds, a surplus driven by pandemic-related disruptions in food service demand. This excess highlights a critical issue: the system designed to balance supply and demand is struggling to adapt to modern market realities.

Consider the dairy farmer in Wisconsin, who relies on government purchases to stabilize prices during oversupply. Yet, as the stockpile grows, so does the cost of storage and maintenance, estimated at $0.10 per pound annually. This financial burden falls on taxpayers, raising questions about the sustainability of the current model. Meanwhile, consumers are increasingly opting for plant-based alternatives, further complicating the demand equation. The challenge lies not just in managing the stockpile but in reimagining its role in a rapidly evolving food landscape.

To address these issues, policymakers must explore innovative solutions. One approach is to redirect surplus cheese to food assistance programs, such as school lunches or food banks, where it can address nutritional gaps. For instance, a pilot program in California successfully distributed 500,000 pounds of cheese to low-income families, reducing waste while supporting public health. Another strategy involves incentivizing dairy farmers to diversify their products, such as producing high-demand items like butter or yogurt, which have shorter shelf lives and lower storage costs.

However, these solutions are not without risks. Diverting cheese to food programs could create dependency, while diversification may strain small-scale farmers lacking the resources to pivot quickly. Additionally, global trade agreements, such as the USMCA, introduce new variables, as export markets become increasingly competitive. The future of cheese reserves hinges on balancing these complexities, requiring a delicate mix of policy innovation, industry collaboration, and consumer engagement.

Ultimately, the cheese stockpile’s survival depends on its ability to evolve. By leveraging technology, such as blockchain for supply chain transparency, and fostering public-private partnerships, the U.S. can transform this challenge into an opportunity. The goal is not just to manage excess but to create a resilient system that supports farmers, feeds communities, and adapts to the demands of the 21st century. The cheese stockpile’s story is far from over—it’s just entering a new chapter.

Quick Potato Shredding: Creative Methods Without a Cheese Grater

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The US maintains a cheese stockpile as part of its agricultural price support programs, primarily to stabilize dairy prices, support farmers, and prevent market oversupply.

The cheese stockpile originated from government programs like the Dairy Product Price Support Program, which began in the 1930s to help dairy farmers by purchasing surplus cheese when prices dropped too low.

The cheese in the stockpile is either sold domestically or exported when market conditions allow, or it is donated to food assistance programs to help those in need.